The global trade in fossil-fuels is proving to be far from simple business. In Norway, which almost entirely generates its internal electricity supply from renewable sources, oil has become dirty laundry. But what can turn national embarrassment into real change? Can art as comment apply just the right amount of social pressure?

‘Black, sir?’ The insistent voice of a stewardess wakes me from a shallow sleep. I nod drowsily and glance out of the plane window, as if to make sure this is real: beneath the roaring jet engines stretches an immense blue expanse of gently rippling water, glistening golden in the midday sun. It does not in the least resemble the dramatic, tempestuous colour palette that I normally associate with the North Sea and that many an artist has tried to capture on canvas. But the surface is as effective as it is deceptive: it hides a dark depth from view.

The stewardess hands me a cardboard cup of coffee, black, black as midnight on a moonless night. The lukewarm drink is not that great really, but sometimes bad coffee is better than none. ‘What would the world be without coffee?’, asks an old man sitting next to me, grinning. I take his question too seriously and my mind wanders to the gloomy sight of rundown coffee bars and neglected social lives, to caffeine-free work meetings on Monday mornings, to underproductivity, stagnant global trade flows and waning economies, unmet deadlines, unfinished books, lack of energy and the alternative supply of various kinds of tea.

Monira Al Qadiri, OR-BIT 1-6 (2016-18). 3D printed plastic, automotive paint, levitation module, Approx. 30 x 30 x 30 cm each. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Markus Johansson.

Anyway, I am obviously not travelling for coffee but for oil. Or rather: for art. As we start to descend, the weather has turned grey. A diffuse light spreads across the fjord landscape. In the distance Stavanger comes into view, the fourth largest city in Norway, an immense country with a mere 5.5 million inhabitants. The picturesque town with its colourful facades is also the heart of the oil industry, a multi-billion-dollar business that has transformed the country since the discovery of undersea oil fields in the 1970s.

Profits were nationalized into the state-owned company Statoil, currently renamed as Equinor. Although 95% of Norway’s electricity production comes from hydroelectric power stations, major capital flows in through the export of oil and gas to foreign countries. The extraction of oil and gas has raised the economic standard of living in rural Norway to previously unimaginable heights. But this one-sided perception – both internal and external – is a sensitive issue today; the initial euphoria has gradually given way to a certain sense of embarrassment.

A drop in the ocean

Experiences of Oil, an exhibition at the Stavanger Art Museum, is a visual offshoot of a conference held in November last year. On the first evening of my press trip, Anne Szefer-Karlsen, co-curator of the exhibition (together with Helga Nyman), invites me to dinner. We meet in the solid wood interior of one of the white-painted houses in the historic city centre.

Right from the start, I express my reservations about yet another artistic manifestation that takes a critical stance towards all kinds of -isms – from extractionism to petro-capitalism to ecofascism – painting a hostile image that is as all-encompassing as it is elusive. How can an ensemble of sixteen artistic positions, brought together within a museum exhibition format, make any significant difference to the powerful, omnipresent fossil fuel industry? Does art have an essential role to play, or is it just a drop in the ocean?

Shirin Sabahi, Pocket Folklore (2018). Found objects, vitrines. Dimensions variable. Mouthful (2018). Digital, color, surround sound, Farsi, Japanese, English with English subtitles. Duration: 35 min 53 sec. Works courtesy of the artist. Photo: Markus Johansson.

During our conversation, Szefer-Karlsen manages to assuage my scepticism to some extent. As a self-proclaimed geek, they enthusiastically talk about the industry they have been immersed in over the past years. Szefer-Karlsen leads me along all kinds of political intrigues, engineering feats and personal testimonies, and turns the black gold into a prism of colour – like an oil slick on wet asphalt. How wonderful it is to feel the profound love in their words, even if the object of their affection is as complex as it is problematic.

Yet is that not what we would call, to use a catchphrase, staying with the trouble? Szefer-Karlsen smiles affably when I tell them that, as if they were getting an encouraging pat on the back from an intellectual ally. Donna Haraway is her name, the same person who wrote that language could provide us with a way out of the climate catastrophe we are currently experiencing. Let us assume that her words are more than a simple witticism.

Climate talks

As long as there are empty planes in the air en masse, there is little reason for optimism. The unprecedented scale of planetary ecocide requires, more than ever, a radical transition thinking that prioritizes ecology over economics and long-term vision over short-term gain. However, goodwill in political or diplomatic circles is sorely lacking due to the entanglement of economic, geopolitical and military interests. Nor are we to expect great results from the effects of climate mitigation.

A gradual replacement of fossil fuels by renewable energy is unfortunately too optimistic a scenario. The Third Carbon Age predicts a further proliferation of hydrofracking and the economic supremacy of peak oil. Opinions, however, are divided as to when exactly the latter will take place. Specialist literature speaks of twin peaks: some claim that we are already in the midst of it, others estimate it to occur in around 2030.

Exhibition view Experiences of oil at Stavanger Art Museum. Artworks from left to right: Farah Al Qasimi, Arrival (2015-2021); Raqs Media Collective, 36 Planes of Emotion (2011); Kiyoshi Yamamoto, Fantasia, descoberta e aprendizagem (2021). Photo: Markus Johansson.

Coincidentally or not, during my visit to Stavanger, there was the COP26 UN climate conference in Glasgow, a fiercely mediatized political spectacle that raised great expectations. Yet at the same time, and despite all good intentions, the UK is planning to give the go-ahead for the exploitation of an oil field to the west of the Shetland Islands in the Scottish North Sea: 800 million oil barrels, the equivalent of twenty-five-years’ energy supply. The hypocrisy of policy decisions such as these will make even the most ardent idealist lose heart.

Material language

In the museum, I am greeted by Raqs Media Collective’s artwork, a modular installation consisting of Plexiglas plates engraved with short phrases. The artists were inspired by a tenth-century Sanskrit manual which aimed to help dancers evoke complex emotions through physical expressions. The way in which language – as an unusual suspect – is poetically linked to oil here is of merit to the curators, also noticeable elsewhere in the exhibition. Raqs Media Collective invited the Norwegian author Øyvind Rimbereid to write a series of new poems, a continuation of his lyrical masterpiece Solaris Corrected (2004), composed in a mixture of Stavanger dialect, German, English, Scottish, Frisian and Old Norse.

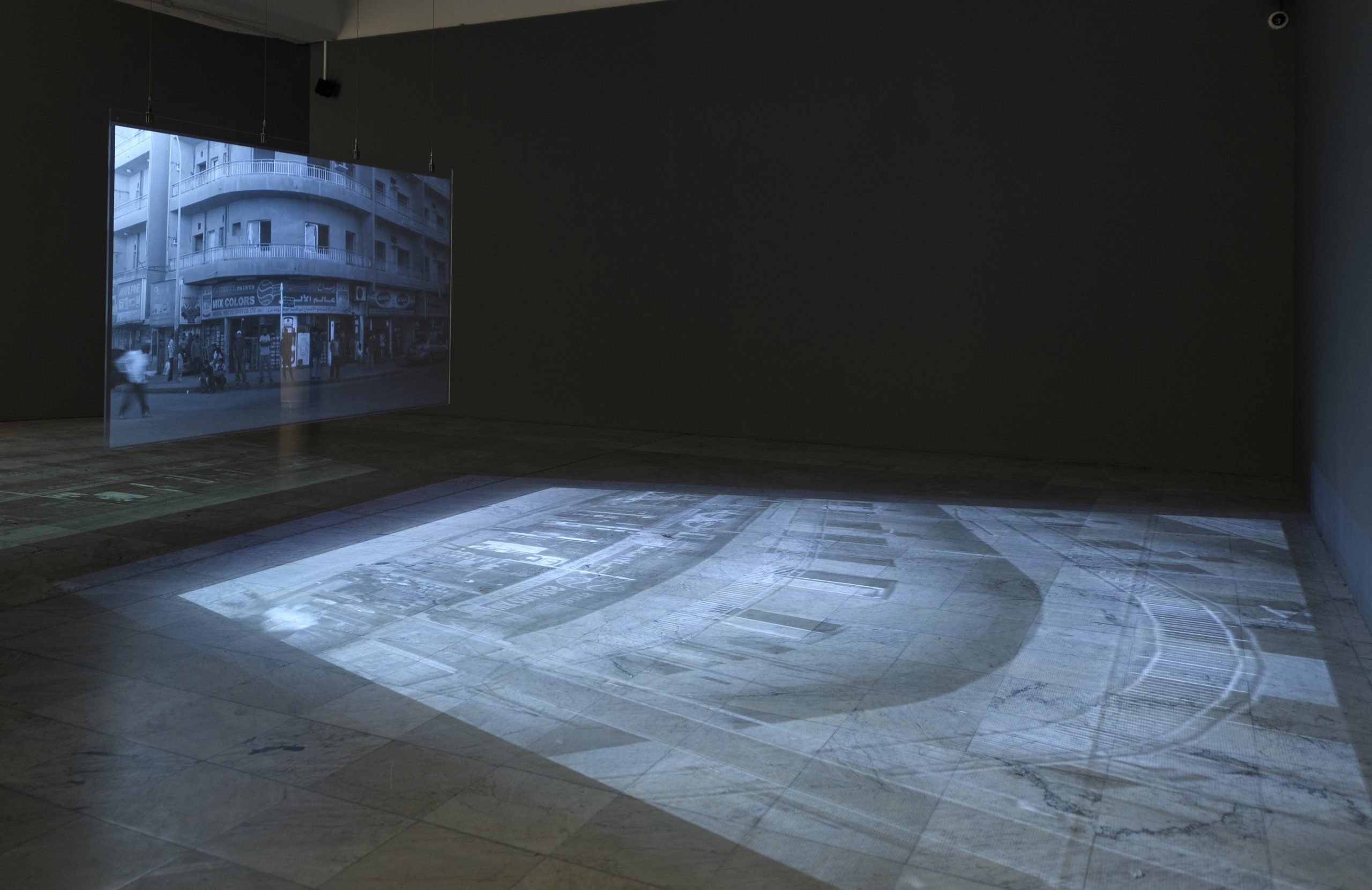

Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Chai Siris, Dilbar (2013). Black-and-white HD video projection with sound, looped, suspended glass pane. Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation. Courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation Collection and the artists. Photo: Markus Johansson.

A little further on, Farah Al Qasimi’s works catch the eye: a series of evocative photographs entitled Arrival (2015-2019), interiors from the Gulf region in which the figures portrayed have been cut or left out. The series of images is presented against a background of photographic blow-ups printed on vinyl wallpaper. A powerful visual reflection on Al Qasimi’s cultural identity and the historical convergences of the photography and oil industries in the region.

Curatorial tightrope walking

Also notable is the contribution of Iranian Shirin Sabahi. Sabahi made a film about Matter and Mind (1977), a sculptural installation by Japanese artist Noriyuki Haragushi that he first made for Documenta 6 and that has since been on permanent display at Tehran’s renowned museum of contemporary art. He filled a large metal basin to the brim with more than five thousand litres of viscous motor oil, a perfectly reflective surface that anticipated Richard Wilson’s monumental installation 20:50 (1987) – which has long been on view at the Saatchi Gallery, London.

For the making of her film Mouthful (2018), Sabahi visited the artist in Japan, and followed the restoration process in the museum. Three display cases contain the everyday trinkets that visitors threw into the oil reservoir, like money into a wishing well – or was it to test the all-too-perfect surface? Sabahi’s poetic installation deliberately hovers between past and present, viewer and work of art, East and West, chance and necessity, art and life, sculpture and architecture, utopia and heterotopia.

Otobong Nkanga, Wetin You Go Do? Oya Na (2020). Multi-channel sound installation, loop 20 min, 28 sec. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Markus Johansson.

In their video Dilbar (2013), Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Chai Siris shed light on the daily lives of Bengali workers in the UAE through enchanting black and white images – ghostly manifestations of a repressed reality. Also in Nigerian-Belgian Otobong Nkanga’s work, language is given a prominent place: Wetin You Go Do? Oya Na (2020), a flawless sound installation with voices spread across several channels, voiced by the artist, in a constant improvisation of language, rhythm and intonation. Nkanga draws attention to language as a locus of consensus and dissensus, as an embodied, gendered practice, able to create new worlds.

In my opinion, Experiences of Oil is at its best in that chiastic interplay between language and world that occurs through aísthēsis – the experience. The phenomenon of oil is unravelled in its inherent complexity without making activist claims or assuming too casual an approach. With a loaded theme like this, curatorial tightrope walking is no easy exercise in any case.

Petroleum museum’s ‘success’ story

Monira Al Qadiri presents a series of floating sculptures: 3D plastic prints covered with iridescent paint that imitate the colour palette of oil and water. Her elegant visual language was inspired by the monstrous drill bits used in oil drilling. In a lecture-performance, Al Qadiri imagines how a future civilization might find the drill heads and assume they are some kind of alien technology. The objectophilic seduction of these industrial artefacts is hard to deny. In fact, I recently spotted them in the work of other artists as well: as part of Oliver Ressler’s project Barricading the Ice Sheets at Camera Austria, Graz, and in an installation by Julian Charrière for the Prix Marcel Duchamp at Centre Pompidou.

Exhibition view Experiences of oil at Stavanger Art Museum. Artworks from left to right: Monira Al Qadiri, OR-BIT 1-6 (2016-18); Brynhild Grødeland Winther, Drawings on paper. Photo: Markus Johansson.

The curious drill bits are also on display at the Stavanger Petroleum Museum – an integral part of the press programme – where they are presented as heroic attributes in a national saga. The museum mainly focuses on telling and perpetuating a success story – the economic blockbuster entitled Norway’s Oil Fairytale – rather than looking critically at the future. However, the guide does his utmost to emphasize that there is no question of commercial interference, since it is a state-funded museum. Yet with a nationalized fund of 1.4 billion US dollars, there is undoubtedly a lot at stake.

The guide consequently hurries his visitors through the section entitled Future Challenges featuring a portrait of the eighteen-year-old Swedish Greta Thunberg. I look up and read a news ticker with Obama’s popular tweet: ‘We are the first generation to feel the effect of climate change and the last generation who can do something about it.’ The urgency of his words sadly remains hanging in thin air. It was not only I who suffered from a slight sense of disgust after this ideological tour: Lili Reynaud-Dewar (laureate of the Prix Marcel Duchamp 2021) also extensively voiced her disgust on Instagram.

Post-oil without oil?

During a walk, a friend tells me of how he found a large oil painting in the street and brought it home, a generic scene of a sailing boat on the high seas. He shows me a photograph that involuntarily reminds me of the painting that Marcel Broodthaers managed to pick up in the touristy Rue Jacob in Paris and that would later become the central subject in his book-film Un Voyage en Mer du Nord (1973-74).

The American art theorist Rosalind Krauss used Broodthaers’ work to discuss the post-medium condition in which contemporary art seems to have fallen into. This is not all that far removed from the curatorial approach of Experiences of Oil, which ignores the dominance of oil as an economic medium or ecological culprit, and seeks out a well-considered dialogue between various media, with scenographic elements reminiscent of a book. It is precisely between these two poles – book and exhibition – that the whole project is situated.

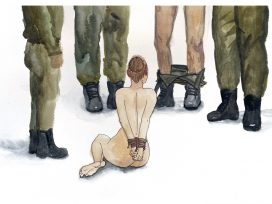

INFRACTIONS (2019). Video installation, drawing printed on textile. Duration: 63 minutes. Photo: Markus Johansson.

And yet a post-oil era does not necessarily imply a world without oil. How do we criticize a phenomenon of which we form an inseparable part? In a well-known essay, Irit Rogoff termed this ‘embodied criticality’: ‘living out the very conditions we are trying to analyse and come to terms with’ – words that seem quite appropriate for an exhibition held in the very heart of the oil industry.

The last day of my press trip includes a cruise through the fjords – being a tourist is a guilty pleasure. Together with a few other journalists and a slight hangover, I board the rather modest vessel. Among the passengers, I recognize some of the guests from the hotel where I had been staying: broad-shouldered, pumped-up men and women who have travelled to Stavanger for the IPF World Powerlifting Championship and with whom I shared the dance floor the previous evening. The party mood seems to have subsided. With a white handkerchief and a proper sense of drama, my friend waves us off from the quay.

Our cruise is touristy, as it should be, replete with an Edvard Grieg soundtrack that musically accompanies the most picturesque scenes and dramatic rock formations. As per the programme, we sail past the Preikestolen – a famous Norwegian landmark – and fill a bucket at the impressive Hengjanefossen waterfall, whose spray kitschily brings out the colours of the light spectrum. A dandy photographer from Forbes excitedly tells me how he has already seen five rainbows that day. I laughingly ask him what on earth he is going to do with all that luck while I sip my coffee, which has a slightly fishy taste, or maybe I’m just imagining it.

Success and happiness?

In the taxi to the airport, the radio plays Falling by Julee Cruise while we leave Stavanger behind us. I think back to the Norwegian fairy tale and the simple fishing village that has grown into a rich port city, the city from the popular drama series State of Happiness (Lykkeland). To be honest, I don’t know what to think of this state of happiness.

By nature, I am suspicious of success stories and happiness formulas. To me, they seem too other-worldly. That is why I am trying to compassionately watch over the dubious fate of a Belgian art journalist, who flew in for a few days with money from the embassy to critique an exhibition about oil, and who now, with an indefinable feeling of doubt, is boarding the plane once again and closing his eyes, into the night.

Published 15 April 2022

Original in English

First published by Rekto:verso

Contributed by Rekto:verso © Pieter Vermeulen / Rekto:verso / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Depuis le référendum d’indépendance de l’Ukraine en 1991, le pays a connu son lot de hauts et de bas. Au cours des trente dernières années, les artistes ukrainiens ont exploré les questions d’identité parmi les ruines de l’utopie, mais n’ont été reconnus que récemment.

Protecting nature, empowering people

Environmental protests in the Balkans

The success of recent protests against extractivism and ecosystem degradation in Serbia and Albania highlights the potential for democratic reinvigoration around ecological issues in south east Europe. But the EU has yet to prove it can act as a credible partner in this process.