Of beasts and men

A bill on Animal Welfare is currently making its way through the UK parliament. If passed, non-human vertebrates would be recognized as sentient. But would this mean that animals have the same or similar rights to humans?

Photo via Pxhere, CC0 Public Domain

Anyone who has accidentally trodden on a cat’s tail knows it has sensations. The purring that follows from a gentle stroke under its chin testifies to its more positive capacity for sensuous pleasure. Yet, until now, there has been no formal recognition that animals are conscious and capable of experiencing joy, pain and suffering.

This finally looks likely to change. The Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill is making its way through the UK parliament. If passed, it will result in the establishment of the Animal Sentience Committee, charged with monitoring if and how government policy might have “an adverse effect on the welfare of animals as sentient beings”. Applying to vertebrates, it will be the first time British law has legally acknowledged that non-humans are conscious. Anything the government does that affects animals, in sectors from farming to construction to transport, will have to account for its impact on animal lives.

It seems extraordinary that such a recognition has taken this long. The stubborn refusal to acknowledge reality, to protect the specialness of whoever “we” humans are, is deep-rooted. In his recent pro-vegan polemic How to Love Animals, Henry Mance points out that as recently as 1976, the journal Hog Farm Management was advising its readers, “Forget the pig is an animal – treat him just like a machine in a factory.” The more “other” animals are, the easier it is to disregard any responsibilities we might have for their welfare.

What follows from this recognition of animal sentience is, however, far from obvious. Animal welfare minister Lord Goldsmith said that passing this law will be “just the first step in our flagship Action Plan for Animal Welfare which will further transform the lives of animals in this country”. Others include ending the export of live animals for slaughter, consulting on reforming labelling so that consumers can more easily buy food that aligns with their “welfare values”, and banning primates as pets.

For many animal rights campaigners, it is assumed that animal rights are on the same trajectory as those for persecuted groups of humans over the last century. As the founder of PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), Ingrid Newkirk, has said, “In the same way that racist and sexist views allowed us to discriminate against minorities and women, speciesism allowed us to inscribe an inferior status on animals and to regard them not as individuals, but as objects and means to fulfil our desires.”

It will become impossible, these activists argue, to continue to kill and eat animals, or even to keep them for eggs and milk. We will be forced to recognize their right to live according to their true natures, experiencing the natural emotions of a wild animal, not the short and stressful existence of livestock. The reasoning seems to be that since we grant humans rights on the basis of their sentience, then animals, if they are indeed sentient, should also be granted the same or similar rights.

Photo by franzl34 from Pixabay

But this apparently simply inference assumes that the basis of human rights is sentience, pure and simple. The reality, however, is far more complex.

Plato, Darwin and the arc of animal welfare

With the combined benefits of science and hindsight, many things that seem obvious to us now were far from evident for most of human history. Yet the accretion of learning can also have the opposite effect, blinding us to things so obvious that only a flawed theory could make us fail to notice them. The real nature and significance of animal sentience surely falls into this category.

Traditional, unindustrialized societies are almost invariably animist. They see everything as being alive: mountains, rivers, plants, animals. The separation of human life into a category somehow distinct from other living matter requires some inventive conceptualization. In the west, this has most obviously come in the form of the doctrine of the immaterial soul that breathes conscious life into otherwise oblivious matter. Adopted by Christianity, then filtered through the lens of a creation myth in which God gave humankind dominion over the other animals, it became a license to disregard their welfare and treat them as merely our tools.

The lack of a soul doesn’t rule out animals having sensations such as pain. It simply creates a hierarchy in creation within which the wellbeing of one kind of creature – humans who possess a soul – matters more than that of any other. So in order to disregard animal welfare there is no need to believe that, despite all appearances, animals have no feelings and awareness. All you need do is believe that somehow this kind of awareness doesn’t matter.

Variants of this trick recur in philosophy, theology and in the implicit beliefs that inform how people see the world. For example, although Descartes is notorious for regarding animals as mere automata, by this he simply meant that they acted automatically, on instinct. He did not believe that they didn’t perceive or feel. This lack of reason was sufficient for Descartes to argue that we are free not only to kill and eat other animals, but to practise vivisection on them, as he himself did.

Aristotle also promoted human exceptionalism, despite arguing that all living things had “souls”. This was not the immaterial self that Plato and later Christianity believed in, but an animating essence. Plants have a generative soul, which allowed growth and reproduction, while animals and humans also have a sensitive soul, which allows them to perceive and feel. Only humans, however, have a rational soul, giving them the capacity to reason and act on more than just instinct.

The crucial moral distinction in western culture, therefore, has not been between sentient and non-sentient life, but between humans, who have reason and/or souls, and other animals, who do not. Although many people have believed that certain animals, such as fish, don’t feel pain, few have doubted the reality of animal sentience altogether. What has varied is our view of how different it is from our own and how much it matters.

That is probably one key reason why the arrival of the theory of evolution did not usher in a new era of concern for animal welfare. Darwin blew away the idea that human beings were created differently from other beasts. We all ultimately shared a common ancestor, and in the case of primates, a recent one too. Our sense of superiority, however, found a way to adapt and mutate to survive this intellectual revolution. Human beings simply became the most evolved of all creatures, at least in terms of our moral and rational capacities. Our shared sentience mattered less than our supposedly unique intelligence.

Nonetheless, Darwin started us down a road that would inevitably lead us to some kind of reckoning and reassessment. The more we have found out about the animal kingdom the less tenable claims to any sharp divide between our capacities and theirs have become. The gap has been shrunk from one side by an increasing acceptance that supposedly unique human capacities have gradually been acknowledged as possessed by animals, and from the other by the realization that so little of what we do is down to our so-called “higher capacities” anyway.

We have learned that we are largely propelled by unconscious processes, cognitive short cuts and instincts. This is what made David Hume remarkably ahead of his time when he wrote of the reason of animals in the 18th century. Animals reasoned, he argued, not because they perform deductions, but because, like us, they generalize from past experience on the basis of inferences rooted more in instinct than in logic.

The unavoidable cruelty of nature

And so here we are in the third decade of the 21st century, finally having to face up to the fact that animals are indeed sentient and that neither our rational capacities nor any supposed immaterial soul puts us in an entirely different category to them. There can be no more turning a blind eye to the horrors of industrial animal farming, of creatures living in cages, of pet dogs doomed to ill health because they have been bred to look cute at the cost of their own wellbeing.

But what now? Ironically it is the very ubiquity of sentience that makes the idea of extending human-like rights to all animals absurd. Nature is overflowing with consciousness but has a total disregard of the welfare of those who possess it. When the sentient eagle carries away the sentient rabbit in its talons, who can imagine the terror of the poor mammal? Salmon may feel pain but the brown bears who feast on them in their dozens don’t make any efforts to reduce it.

Traditionally, philosophers have been unimpressed by attempts to defend the killing of animals on the basis that animals kill each other. It looks like an embarrassing example of the is-ought fallacy: just because something is the case, that doesn’t mean it ought to be. Animals do all sorts of cruel things and that cannot justify us doing the same. To put it even more clearly, just because something is natural does not make it right.

But as Benjamin Franklin recorded in his autobiography, there is something about acknowledging head-on the cruelty of nature that makes any refusal to partake in it seem futile. At one point, Franklin had become a vegetarian, and when he set off one day on a fishing boat he still considered “the taking every fish as a kind of unprovoked murder, since none of them had or ever could do us any injury that might justify the slaughter”.

Franklin’s resolve weakened when, out of the frying pan, the cod smelled “admirably well”. He found himself “balanced some time between principle and inclination”. What finally tipped the scales was seeing smaller fish taken out of the stomachs of cods when they were opened. “Then thought I, ‘If you eat one another, I don’t see why we mayn’t eat you’.”

Franklin was candid about his baser motivations, and acknowledged that his line of thought hardly constituted a sound, rational argument. But his change of heart was not simply a victory of greed over principle. He was indeed using his intellect, not to follow a line of argument, but to attend more carefully to the fundamental truths that must inform our moral thinking.

The error of human exceptionalism

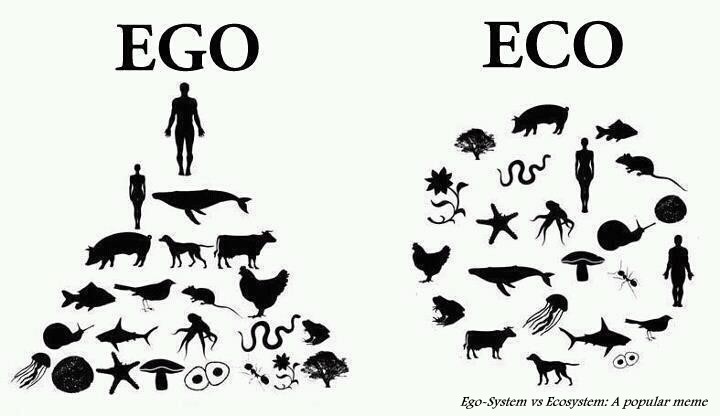

Ego-System vs Ecosystem: A popular meme

What Franklin perhaps realized is that to refrain from all forms of animal killing is not to show due respect to nature, but to misunderstand it. If you do truly understand nature, you see that death and killing are inextricable parts of it. To attempt to stand aside from it is, ironically, to repeat the mistake of human exceptionalism, by encouraging human beings to separate themselves from the harsh realities of a food system that cannot function with herbivores alone. People who really do have a feel for nature have greater genuine reverence for animal life than those whose alienation from it makes them repulsed by the idea of killing animals.

Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and The Sea captures this brilliantly. The protagonist spends most of the book in pursuit of a marlin. Yet he empathizes with the fish more than any vegetarian land-lubber ever could, and several lines combine almost religious reverence of it with a willingness to kill it. “I love you and respect you very much,” he says to the marlin. “But I will kill you dead before this day ends.” For the old man, reverence does not stop the killing, but it does change the way it is done.

Hemingway may well have been a cruel bastard who once boasted of shooting a dog in such a way that it would take days to bleed to death. But still, his fictional character may be spot on, even if Hemingway himself was not. And if we look at how traditional hunters and pastoralists feel towards the animals they eat, it certainly seems that Hemingway was on to something. The preferred foods of the Maasai, one such group of pastoralists that inhabit a region encompassing northern Tanzania and southern Kenya, are meat, milk and blood. Their kinship with their herds is so close that their word for cattle, inkishu, is also used for the Maasai as a people. Most East African pastoralists also share names with their favoured ox.

The Inuit also closely identify with the seal that they hunt, kill and eat. They believe both hunter and seal benefit from the hunting and that the “agreement” of the seals to be eaten is necessary for the animals to reproduce. The blood of an Inuit requires the blood of seals to make it thick and strong, unlike the watery blood of non-Inuit. “Seal blood gives us our blood. Seal is life-giving,” says one elder. “Inuit blood is thick and dark like the seal we eat,” says another.

Time and again we find that the closer human beings have been to nature’s natural cycles of life and death, the more they both respect other animals and are willing to eat them. This is not a flaw of “primitive” people but a profound understanding of the true meaning of kinship with other creatures that is lost in more industrialized cultures.

As inconsequential as sardines

There is one way in which traditional attitudes to nature do reflect an innocence that can no longer be maintained. The ways in which killing is ritualized and given spiritual significance speak to a seeming need among humans to give meaning to what would otherwise be a pointless cycle of life and death. But a hard-nosed, humanist view would be that it is simply all ultimately meaningless.

The sheer quantity of death and killing in nature is awe-inspiring. Eagles bring a constant supply of small mammals and birds back to their nests to feed their young. Shoals of millions of sardines are fodder for larger predators like dolphins, who eat 25 to 50 pounds of fish every day. The degree of death and suffering in the natural world would be gratuitous if it were the product of design. If God exists, he must be some kind of sadist.

If human beings are part of nature, then our own lives risk seeming as meaningless as those of wild prey. But the option of making ourselves an exception seems to be no longer tenable. So a tempting alternative is to give more significance to animal lives, to make them more important and so defend our own importance indirectly. But an honest look at nature will always tell us that although animals can feel joy or pain, at the end of the day their lives have no further meaning.

So it seems we are on the fork of a dilemma. We can no longer see human beings as being completely separate from nature, and think of animal suffering as of no importance whatsoever. But if we put ourselves on the same level as the other animals, either we have to accept that our own deaths are as inconsequential in the grand scheme of things as those of krill and sardines, or we have to make animal death so meaningful that we strive to avoid it, in a world in which such efforts are as futile as trying to stop the rains.

Perhaps there is another way of reconciling the realities of animal sentience and the inexorable cycles of killing and eating. We have to start by recognizing that what makes human life worth preserving is not the mere fact that it is sentient. Human rationality and self-consciousness may not be entirely distinct from that of other animals, but it is far more developed. Even the most intelligent of other animals only ever lives instinctively. No dolphin has ever gone off and started an alternative dolphin community based on novel political values, and whales do not choose to be childless because they have other desires that matter more to them. Human culture is uniquely diverse and distant from our species’ rawest evolutionary imperatives of survival and reproduction.

That may or may not make us better. But it does make us different. Most obviously, it makes full-blown morality possible: we can choose our actions on the basis of what we judge to be right or wrong, not merely on what instinct compels us to think and do. So we could refrain, for example, from killing other animals, something my cat could never do. But the fact that we can do this doesn’t mean that we should. The argument that we should avoid inflicting unnecessary suffering is strong, but given the necessity of death and killing in nature, we need more reasons to avoid ending life.

Our human difference gives us reasons not to kill each other that go beyond simplistic injunctions to never kill or never shorten life at all. Unlike other animals, we do not live just in the present. Our memories, plans and projects matter to us in ways that are inconceivable for any other creature. When you kill any animal, you frustrate its natural desire to live. But when you kill a human being, you close off the possibility of a future of near infinite variability, which is not just one of doing what our kind naturally does. That is what opens up the possibility of human life having real meaning. We can create narratives for our lives, reflect on what we value and cherish it.

I have no doubt that animal lives can be worth living. I believe my cat has a good life and that to end it for no reason at all would be pointless. But my cat is also a heartless killer who will play with prey and leave it for dead. When he dies, another light will go out in the universe but no aspiration will have gone unfulfilled, other than a simple desire to stay alive. His death will be a cause for sadness but only because the sadness of death is the necessary companion of the joy of being alive. Life is and can only be full of the wonder of being alive, the pain of suffering and the sadness of good things passing.

To recognize properly the reality of animal sentience requires us to accept that conscious life is the light that flickers all too briefly in an otherwise dark universe. It is wonderful but it never lasts, and if we measured its value by its length the whole of nature would seem worthless.

Ending the horror of mass industrial farming

Photo by Paul Harrop / Model farm animals, Eastrington via Wikimedia Commons

To truly value sentience requires just two things. The first is never to cause more suffering to anything than is necessary. What should appal us is not that we eat the other animals but that we often keep them in such dreadful conditions before putting them out of their misery. The second is to treat them with the same reverence that traditional hunters, pastoralists, farmers and fishers have. We need to respect animals for the fleeting eruptions of consciousness that they are, not as though they had human-like life projects that we have cruelly cut short.

At present, the vast majority of humankind errs in opposite directions. Most fail to respect animal sentience at all, treating livestock like meat machines. A growing minority, however, think of animals as though they were cuddly versions of ourselves – creatures who deserve a long life and for whom death at anything other than an old age is a tragedy rather than a common fact of life. They are in denial, like the vegan cat-lover who refuses their companion animal meat. To love a cat and yet not accept the way it naturally lives is not to truly love it at all, but simply to adore a sentimentalised, sanitised version of it.

Our choices about animal welfare reflect these two extremes. If humankind became vegan, all we would be doing is separating ourselves from the harsh realities of animal life. Death and suffering would still go on; we would merely have washed our hands of it. If we carry on as we are, we are making nature even crueller than it already is. The eagle’s prey has a horrible death, but such torture is fleeting compared to that of too many farm animals.

If, on the other hand, we keep only as much livestock as we humanely can and treat it well, then we improve upon nature. This needs to be no more than the planet can sustain, but while it requires much less animal husbandry than we have under mass industrial farming, it is significantly more than zero.

In such a future, the animals under our stewardship would have easier lives than those of their wild cousins, with medicines when they are sick and a compassionate painless death when their time comes. The sentience we would then honour would be of an authentic kind: the in-the-present wonder of any conscious animal, whose life is incredible, but which never has any greater meaning and cannot be made more meaningful simply by virtue of being made longer.

This piece was first published in New Humanist Winter 2021 and reviewed by Eurozine.

Published 19 January 2022

Original in English

First published by New Humanist Winter 2021

Contributed by New Humanist © Julian Baggini / New Humanist / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Jürgen Habermas recently argued that the pandemic measures of the German government hadn’t gone far enough. To weigh the state’s duty to protect life against other rights and freedoms was unconstitutional, he warned. In the ensuing controversy, critics accused him of authoritarianism. Were they right?

In Poland, a weak democratic culture collides with unfamiliarity with the historical values of the European Union. Rebuilding the rule of law means explaining to citizens that the constitution is there to protect them. The alternative may be Polexit.