Romania: Propaganda into votes

Romania’s anti-vax movement has mutated into a pro-Russian protest bloc. Representing a politically disenchanted online public, the far-right Alliance for the Union of Romanians is increasingly influencing the mainstream agenda.

Romania’s elections at the end of 2020 left society divided and the country’s politics unstable. The liberal coalition was short-lived, after conflict between the National Liberal Party (PNL) and the Save Romania Union (USR) led to the collapse of the government in just under a year. Three months before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the PNL ended the chaos by forming a coalition with the Social Democratic Party (PSD), together with the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR). The 70% supermajority obtained by this grand coalition – the second in the country’s post-communist history – has brought stability, but at what cost?

Having advertised itself as a progressive and reformed alternative to the PSD during the electoral campaign in 2020, the PNL decided that the money coming in through the European Commission’s National Recovery and Resilience fund was worth the price of an alliance with its arch-rival. Once again, Romanian political parties showed that they are primarily opportunistic and love money more than anything else.

The thirst for power of the so-called National Coalition for Romania has led to a significant regression for democracy. A highly controversial bill that would give impunity and increased powers to the Romanian Intelligence Service is just one symptom of the decay of rule of law. Corruption and clientelism remains a major issue of concern, most recently in connection with the Anghel Saligny rural infrastructure project.

In the 2022 Democracy Index published by The Economist Intelligence Unit, Romania is categorized as a flawed democracy, scoring 3.75 out of 10 for political culture among politicians and citizens. Romanians no longer trust politicians, disbelief in democracy is rife and political apathy is skyrocketing.

In this situation, extremism lands on fertile ground. The entry of the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) in the parliament in 2020 after the lowest turnout for an election since the fall of communism (31%) caught many by surprise. Since then, however, hard-line nationalist discourse has entered the mainstream. According to current polling, AUR is predicted to win up to 20% of the vote in 2024.

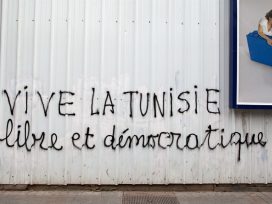

Bucharest 2019. Image: Babu. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Blaming the war

Romanian politicians say one thing in Brussels and NATO, and another thing at home. Officially, the government condemns Russia’s invasion and unconditionally supports the Ukrainian cause, which includes supplying arms. But in reality, political backing for Ukraine is half-hearted at best. After the invasion, Romanian leaders visited Kyiv long their central European and Baltic counterparts, apparently treating the exercise as an obligation more than a genuine gesture of solidarity. While the government has followed public opinion in helping Ukrainian refugees, its lack of enthusiasm or initiative at the foreign policy level has shown its real disinterest in Ukraine.

When convenient, however, our politicians do not hesitate to use the war for political ends. Rising energy prices have been explained away as an inevitable consequence of the war, but there has been no thought about taking responsibility for reforms. Romania’s natural gas reserves are large enough not only for the country to become energy independent but also for it to supply to neighbouring countries. The war has also been blamed for inflation, which last winter reached 16%. Predictably, people have grown tired of the narrative.

On 8 October 2022, Romania’s Minister of Defence, Vasile Dîncu, gave an interview in which he contradicted the country’s pro-Ukrainian stance. The only way to peace, Dîncu argued, would be for Ukraine to negotiate with Russia. His statement was quoted extensively by the Russian press, eventually forcing the minister to resign. At first it seemed that Dîncu had been unanimously condemned by the coalition. But subsequent statements by Romanian politicians have cast doubt on whether he was the only member of the country’s leadership with such views. If politicians don’t understand the stakes themselves, how can they explain them to the population?

New nationalism

It should not be forgotten that Romania and Ukraine did not have deep political or socio-cultural relations before the war. For Romania, the wave of Ukrainian refugees was the first event of this kind (over 2.4 million Ukrainians have sought refuge in Romania since the invasion), and the willingness of the Romanians to help was a positive surprise. But as the war continues, citizens are increasingly feeling the economic repercussions of instability in the region. Far-right nationalist influencers have not let this opportunity go to waste.

But who are we talking about when we say nationalist or extremist figures in Romania? What is their impact and what messages are they spreading?

After the 2020 elections, the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) became the face of nationalism. The party was founded in 2019 during the COVID-19 pandemic as the country’s sole openly anti-vaccine party and numerous AUR figures made names for themselves as anti-vaxxers. The most prominent are George Simion, the current leader, and Diana Sosoaca, a former member and current senator. Also in the AUR orbit are far-right influencers such as Oana Lovin and the lawyer Gheorghe Piperea, to name just two of the many who have tried to remain relevant online post-Covid.

Immediately after the invasion, AUR did not rush to take an overtly anti-Ukraine stance and instead aligned more with Victor Orbán-style ‘pacifism’. Since then, however, its position has become clearly pro-Russian, with AUR-affiliated anti-vax Facebook groups and influencers largely migrating to anti-West and anti-Ukraine positions.

Take the ‘pro-peace’ narrative, one that has had limited success and was mainly promoted by Sosoaca and Ana Maria Gavrilă, a former member of AUR and now an independent member of the Romanian Parliament. In a speech to the parliament on the 3 March 2023, Gavrilă claimed that western powers were willing to sacrifice small countries like Romania to their geopolitical goals; the war, she claimed, would be brought onto Romanian soil and into Romanians’ houses. The video of the speech has had over 1.2 million views and over 42.000 shares on Facebook (the most used social network in Romania). While it had no impact on the state’s positions or the overall understanding of why Romania must support Ukraine, it did create a false need for ‘further discussion’.

Sosoaca plays in another league altogether. A lawyer and MP, she became known during the pandemic thanks to speeches in the Romanian senate popularizing the slogan: ‘down with the muzzle’. Sosoaca left the AUR in February 2021 and founded the far-right party SOS Romania in 2022. Recent polls estimate that the party could get close to 5% at the parliamentary elections in 2024, which would be enough to assure her a seat.

How did Sosoaca stay relevant after leaving the AUR? At the beginning of the war, her pro-Russia stance, her meetings at the Russian Embassy and pro-peace protests caused a dramatic drop in her popularity. For historical reasons, most Romanians are anti-Russian and anyway, people had other priorities. Facebook started flagging her content with a disclaimer of possible Russian funding and the Moldovan government shut down sputnik.md, one of Sosoaca’s main online multipliers.

However, disinformation finds other ways to penetrate Romanian society. Sosoaca’s career was rescued when online news channel ZEUS-TV started featuring viral Facebook broadcasts of her parliamentary activity. Registered in 2020, ZEUS-TV now has 657,000 online followers and a Facebook Live interaction of over 1 million. The biggest source of traffic to the ZEUS-TV website is the personal Facebook page of its founder, the talk-show celebrity Luis Lazarus.

The more Sosoaca’s popularity grows, the more radical her messages become. On 20 March 2023, Sosoaca submitted to the senate a proposal to amend the law on the ratification of the ‘Treaty on good neighbourly relations and cooperation between Romania and Ukraine’. Under the pretext of historical reparations, the proposal calls for the annexation of Ukrainian territories historically belonging to Romania (northern Bukovina, Hertsa, Bugeac, northern Maramureș and Snake Island). Sosoaca was heavily criticized by Ukraine, but there has been no reaction from the Romanian government.

The bombastic Sosoaca is not the only, nor even the most dangerous anti-Ukraine figure. This accolade goes to the AUR leader George Simion, who with nearly 1.3 million followers on Facebook dominates online reach on anti-EU and anti-Ukrainian topics. Even though AUR claims to be a pro-European party, Simion blames the EU for the energy crisis and Romanian politicians for turning the country into a colony of global powers.

Mainstreaming the far-right

So far, so predictable. But what is surprising, perhaps, is the decision of the ruling Social Democratic Party (PSD) to appropriate some of the same populist narratives to gain a few more percentage points, even if outwardly the PSD is a pro-Ukrainian party.

The best example of this is the scandal around the minority law adopted by Ukraine in December 2022 as a requirement of its EU alignment process, supplementing the Ukrainian regulatory framework on the protection of the rights of persons belonging to national minorities. In adopting the law, the Ukrainian government failed to grant the Romanian minority full linguistic rights for fear that this would also require it to grant additional linguistic rights for other minorities, including ethnic Russians. While there are legitimate concerns about the law, fears expressed by Romanian politicians and the media that it would restrict the existing linguistic rights of the Romanian minority in Ukraine are unfounded.

The alarmist reaction from the AUR and other far-right influencers was by no means harmless. Even more problematic, however, was the scandalization of the issue from mainstream Romanian politicians. Even the Romanian Foreign Ministry issued a statement criticizing the decision, which was massively shared. The possible negative effects of an anti-Ukraine stance and the impact of using the same rhetoric as the far-right were apparently not considered.

These communication mistakes – if that is what they were – are another example of Romanian politicians’ refusal to adapt to the context of war. Negotiations with Ukraine over the law could have been carried out without giving credibility to pro-Kremlin actors that attack Ukraine at every opportunity. Who benefited from the controversy? Extremists, of course: Diana Sosoaca and SOS Romania, George Simion and AUR, not to mention all the disinformation channels that viralized the news.

The losers were Ukrainian refugees, who once again became an example of ‘how good we Romanians are to Ukraine, and look what we get in return’. Of course, Romania’s official position did not change: after talks between the two country’s presidents, the issue was buried. But the harm had been done and no official correction of the situation or clarification from Romanian authorities was forthcoming.

This scandal only set the stage for an even bigger one that began in early 2023: the controversy over the Bystroye canal, which has eroded support for Ukraine in the public eye more than any other issue. Until 2023 the issue was a dormant dispute between Romania and Ukraine over the impact of deepening the canal linking the Black Sea and the Danube Delta ecosystem in Romania. In February 2023, however, the Romanian authorities raised concerns that works on the waterway through the shared Danube Delta would threaten wildlife in the UNESCO World Heritage Site and break international environmental protection treaties. All these are legitimate concerns, even if it is unclear whether they are justified. Again, however, the problem was the public reaction.

Due to politicians’ eagerness for pre-election popularity, statements condemning Ukraine for illegal work on the Bystroye canal went viral. The scandal erupted on 15 February, after transport minister Sorin Grindeanu said that ‘there are signs that Ukraine is currently dredging the Bystroye channel, which could have an impact on the environment and the Danube Delta’. Following talks between Romania, Ukraine and the European Commission, Ukraine announced that it would ask the Ministry of Defence in Kyiv to allow Romanian inspectors to measure the depth on the Chilia arm and the Bastia canal and that it would stop all dredging.

But this was not the end of it. The leader of the Social Democratic Party, Marcel Ciolacu, published a Facebook advertisement stating that ‘the Romanian people do not accept being left without this wonder of nature that is the Danube Delta! … The Romanian authorities must take swift decisions so that the works on Bystroye stop immediately and the situation can return to normal.’ Simion even went to the Danube Delta and did Facebook lives on site, bringing the issue to the top of the AUR agenda for several weeks. Sure enough, the popularity ratings of both the PSD and AUR rose.

It was no surprise that this scandal was kept alive by the Romanian media. Since the pandemic, political parties have bought either the silence or the attention of the press through contracts worth hundreds of thousands of euros. The money comes from the state budget, of course. A documentary drawing on evidence from the think tank Expert Forum revealed how public subsidies for party advertising in Romania have led to a massive decline in the quality of the press in recent years.

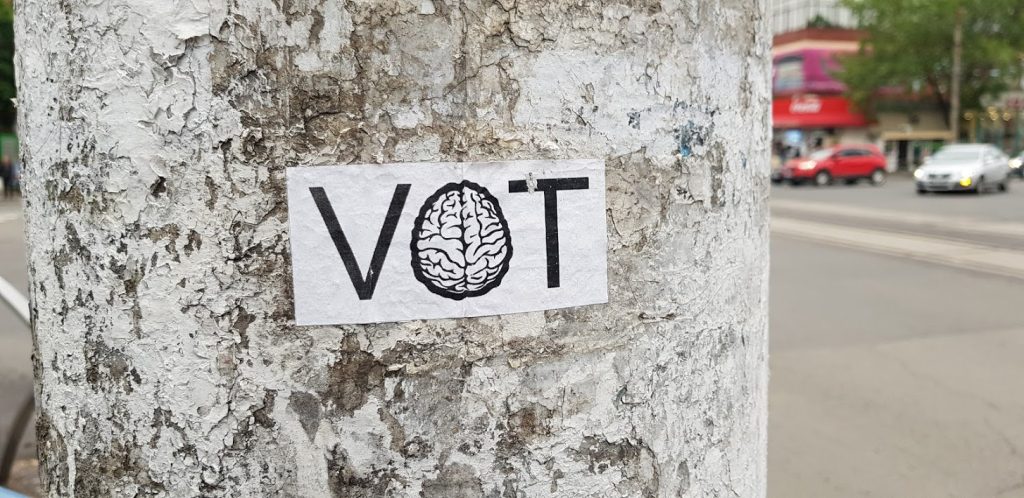

Who benefits from this internal mess? Certainly not Romanian democracy. We are already seeing the consequences of years of political instability as Romania moves away from the rule of law and good governance. Next year will be historic for the country, with local, parliamentary, parliamentary and presidential elections. The risk that anti-western parties, above all AUR, will have a strong voice in the Romanian Parliament is already palpable. After all, online propaganda translates into votes.

Romania’s position towards Ukraine and the European Union dictates the future and security of the country. In the absence of leaders who set clear priorities, years of work in building a functioning democracy threaten to be reversed. The flourishing of disinformation is yet another symptom of a passive state, waiting for solutions while being destroyed from within.

Published 30 May 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Madalina Voinea / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

- The end of Tunisia’s spring?

- Protecting nature, empowering people

- Albania: Obstructed democracy

- Romania: Propaganda into votes

- The myth of sudden death

- Hungary: From housing justice to municipal opposition

- Czech Republic: Velvet contradictions

- Armenia: Light in the dark?

- Moldova: End of the experiment?

- Serbia: Setting sail for Brussels, tying up in Moscow

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Reforms that would bring Albania further towards EU accession remain hampered by corruption and lack of political will. Prime minister Edi Rama, now into his third term and without a serious challenger, embodies the contradictions of the West Balkan country’s hybrid democratic system.

Although it makes for a great dramatic effect, the theories of the sudden death of democracy disregard the gradual erosion and capture of institutions, and the role of the populace – argues political scientist John Keane.