A bill on Animal Welfare is currently making its way through the UK parliament. If passed, non-human vertebrates would be recognized as sentient. But would this mean that animals have the same or similar rights to humans?

Reading faces has no place in law books. Yet the assessment of appearance and demeanour, largely unspoken, still plays a role in ascertaining truth in court. Unscientific and obscure, this practice can lead to discrimination targeting specific ethnic groups.

The pandemic has meant most court hearings are now conducted online. For some of the judiciary, these virtual hearings are a great modernising development. Others are less enthusiastic. That is perhaps not surprising given that our courts are one of the most conservative of our institutions. Its priests appear in wigs and robes, its natural language is Latin, cameras and the press are largely shut out. In this context, trial by Skype is a polarising reform. But some judges complain that there is an insoluble problem when trials are held remotely: reading faces.

In a precedent-setting case at the start of the pandemic – known only as the matter of ‘P (A Child: Remote Hearing)’ – a senior judge overturned a decision to hold a virtual trial. A local authority had accused a mother of child abuse by fabricating and inducing symptoms of illness in her daughter: a case, social services argued, of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy.

The judge ruled the virtual trial could not proceed because the postage stamp version of the mother on Skype was too small. He wanted to see her properly, not only while she was giving her evidence, but while she was sitting in the well of the court and reacting to the evidence against her. This assessment of outward appearance, the judge said, was crucial to judging.

The judgment in P stands for a long and largely unquestioned tradition that asserts judges can and should try to read people’s facial expressions and body language when reaching decisions. But increasingly, both the ethics and science behind this practice are being called into question.

Photo by Smuconlaw., CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

In my first year of training as a barrister in the UK, I arrived at court to represent one of two parents involved in a bitter custody dispute over their young son. The judge – sensing the animosity in the room – warned both of them to be respectful when the other was speaking. He then expressed a sentiment that I have heard many judges repeat, something along these lines: ‘Judges often learn far more watching you while you are listening, than when you are speaking on oath.’

Not long after, in a domestic violence case in a different court, I learned what could happen when the warning wasn’t heeded. While listening to her ex-husband’s answers to questions, my client sighed, made faces and – worst of all – committed the crime of kissing her teeth: an acceptable way of expressing disapproval in her West African culture but a noise that is strangely hated in much of Europe (‘le tchip’ as it is known in French, is now banned in many schools both in France and in the UK).

When the court’s judgment was given, my client was described by the judge as a woman whose behaviour in court had not been consistent with that of a domestic abuse victim. By the narrowest of margins, however, and due to other evidence, the judge (seemingly grudgingly) found in her favour. I was relieved my client won her case, but I was troubled by the idea that even people who have been ruled to be victims may not have a courtroom demeanour that lives up to the imagined standard of what a victim should look like.

I couldn’t help wondering how juries in criminal trials approached similar questions. One of my former lecturers at law school, Professor Louise Ellison, has investigated how juries make decisions in rape cases. Her research suggests that many jurors may have little understanding of the factors that could influence a rape complainant’s demeanour in court. Although victims of trauma may present as calm for a number of reasons, Ellison’s jurors were struck and perplexed with what they perceived as ‘stoic’ testimony by a complainant. Some speculated whether the witness’s measured pace and somewhat ‘flat’ intonation meant that her answers had been rehearsed.

A complication for Ellison’s research is access to jurors. Her studies have been undertaken with actors in the roles of complainants. While criminal trials are held in public, jurors are forbidden, at risk of imprisonment, from revealing how they reached their verdicts. There is an anxiety as to how many mistrials might take place were jurors to reveal their deliberations. In one study, conducted with Ellison’s

colleague Professor Vanessa Munro and published in the British Journal of Criminology in 2009, their mock jurors often said troubling things. One discussion focused on what the witness had chosen to wear to court – with a juror suggesting that a ‘dowdy’ dress was a deliberate attempt to manipulate the jury: ‘she’s got no make-up on, her hair’s tied back, she looks like a frightened little woman. Who knows, in the office she could have black stockings on, four and a half inch heels, wearing loads of makeup.’ Do these mirror the discussions of juries in real trials?

Some think the answers to these types of questions could do immense damage to the system: the right to be judged by a jury of one’s peers, ever since it was enshrined in the Magna Carta, has long been seen as a safeguard against tyranny and a fundamental part of British justice.

There may, however, be ways of improving the system. Much like in other social situations, jurors can and do correct each other. And judges can also help. Ellison has argued for the extension of educative directions given by judges to juries. For example, in sexual offence cases, where there has been a delay between an offence and a police complaint, judges already have a standard direction to warn juries that victims may react in different ways: ‘Some may complain immediately. Others may feel, for example, afraid, shocked, ashamed, confused or even guilty and may not speak out until some time has passed.’

But what happens when judges themselves believe that there is a common standard of demeanour for honest witnesses or for ‘real’ victims? What guidance could they give to juries on how to read a face?

The understanding of the connection between inward thought and outward appearance is centuries old: Aristotle considered that those who blinked too often were indecisive; Freud said that no one keeps a secret – ‘if his lips are silent, he chatters with his fingertips; betrayal oozes out of him at every pore’.

Anyone who seeks to persuade a court may need to project confidence. Evidence suggests that people often equate it with credibility, despite the fact that habitual liars may fidget and blink less precisely for this reason.

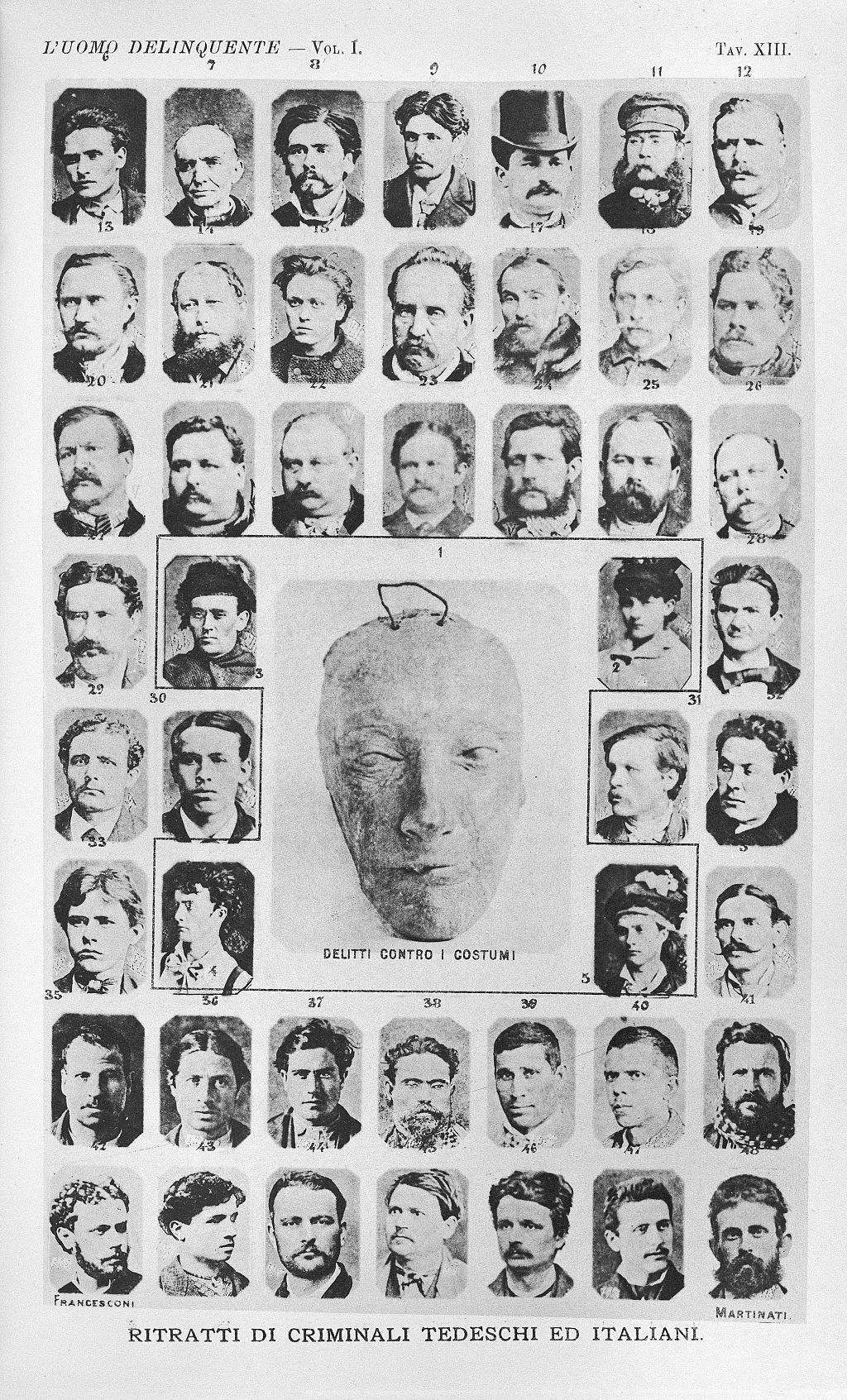

But there are fixed aspects of our appearance over which we have no control. When Cesare Lombroso published L’Uomo Deliquente (The Criminal Man) in 1876, the practice of physiognomy was at its height. His theory that criminality, as an inherited genetic trait, could be identified by physical features such as heavy jaws or a sloping forehead, can be seen in the antagonists of much of 19thcentury fiction. Lombroso claimed to be able to identify genius and insanity in the same way – arguing that George Eliot’s ‘masculine’ face and big skull were evidence of what he described as both her genius and degenerative traits.

Lombroso, Cesare (1836-1909) Cesare Lombroso, l’Uomo Delinquente, Turin: Fratelli Bocca Editori, 1889. Volume I Table XIII 47 Photographs of criminals, with mask in the centre. Image from Wellcome Collections via Wikipedia Commons.

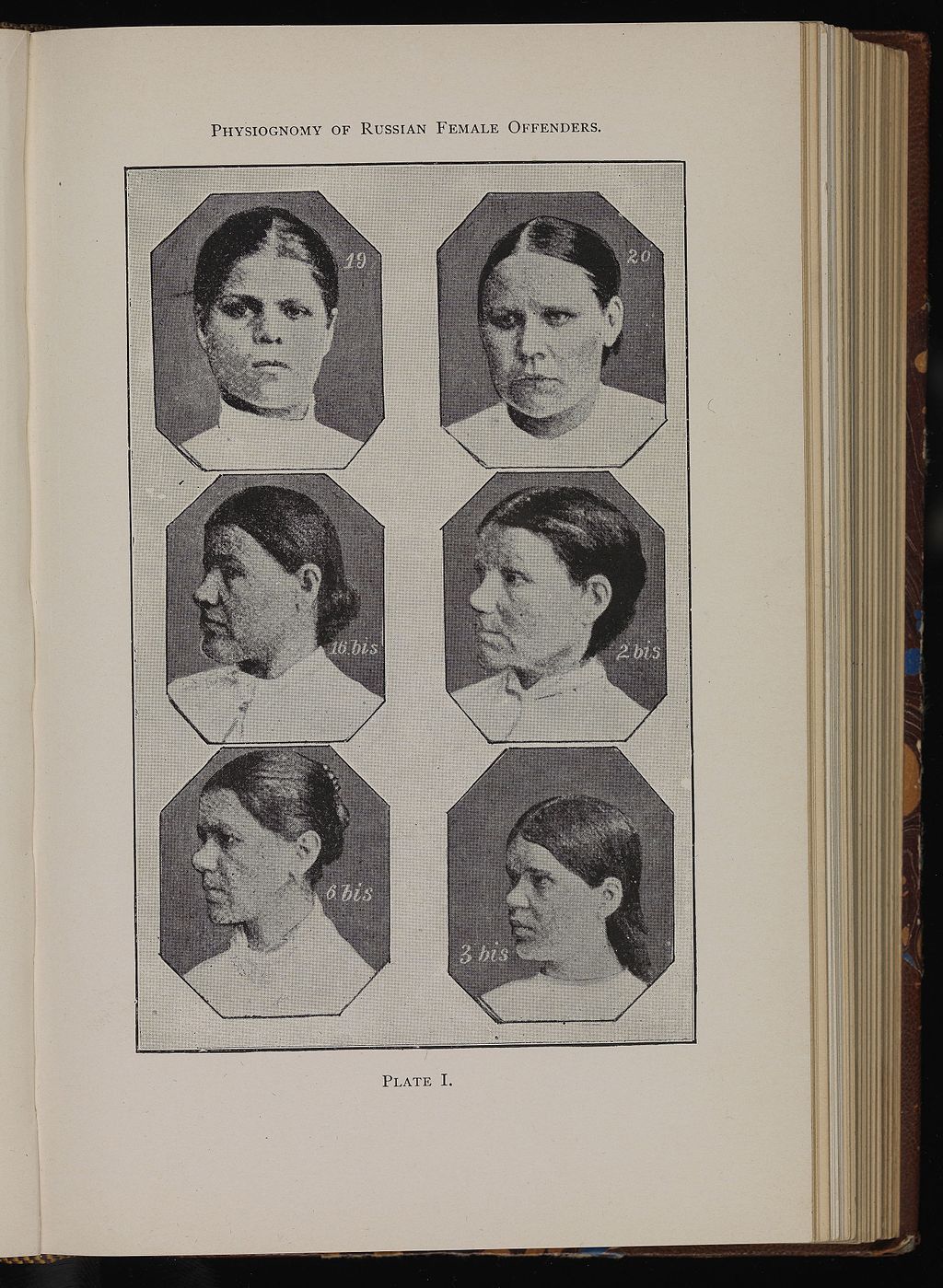

The belief that physical characteristics were associated with character traits would eventually find a home in fascist views on race, sex and eugenics, and are now almost universally discredited. But there was an attack on Lombroso’s methods in his own lifetime. Leo Tolstoy was reportedly disgusted by Lombroso’s ideas of the born criminal. Following a meeting between the two men, the Russian author wrote in his diary that Lombroso was an ‘ingenuous and limited old man’ and then savaged his beliefs in a courtroom scene in his novel Resurrection. In Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, in which much is written about what can be read in a face, the anarchist Karl Yundt also declares that ‘Lombroso is an ass’.

But while the practice of judging character by the immutable structure of a face is now seen as pseudo-science, faith in our ability to read secrets in its changing expressions survives. Pre-Covid, when the only face coverings worn in court were the niqab and burka, courts often directed women to remove them before giving evidence. Lady Hale, the former President of the Supreme Court, justified the practice in a speech to the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, noting that even Quranic sources suggested that in court, they should be lifted. It was a balance, she said, to be struck between the right of religious expression and the entitlement to a fair trial: the use of a person’s facial expressions, body language and demeanour to assess credibility was said to be something we took for granted in this country. Lady Hale said she had, herself, with reluctance, once directed a woman in full purdah to remove a face covering. She felt that doing so had helped her see that the woman was at times lying – but she did not reveal what exactly she had seen beneath the veil.

Physiognomy of Russian Female Offenders. Plate I. From the title “The female offender / by Cæsar Lombroso and William Ferrero”. Image from Wellcome Collections via Wikipedia Commons.

The principles that judges use to read faces are rarely articulated because they are not rules of law at all. They fall under what is termed judgecraft: what one judicial training manual describes as encompassing ‘everything that you will not find in a book on law, evidence or procedure’. Should rules which may mean the difference between innocence and guilt be left so obscure?

When judges are too explicit in their analysis of a witness’s appearance, they risk charges of foolishness. Justice Caulfield’s description of Lady Archer is still remembered: when the Deputy Chairman of the Tory Party, Jeffrey Archer, sued the Daily Star for libel in 1987 for alleging that he had paid a sex worker, the court relied heavily on the evidence of his wife. In his summing up to the jury, Justice Caulfield described Lady Archer as a vision of ‘elegance, fragrance and vision’ when assessing her credibility. He went on to ask whether Jeffrey Archer could really have been in need of ‘cold, unloving, rubber-insulated sex’. Archer won his case and received a record-breaking sum in damages, only to be jailed after a subsequent trial proved conclusively that he had asked a friend for a false alibi.

Still worse was a ruling in 2019, from an unidentified immigration judge who refused a gay asylum seeker’s appeal on the basis that he did not have the ‘demeanour’ of a gay man. The decision was successfully appealed, but one wonders what happens in the many cases where an analysis of demeanour is made but not plainly recorded.

There is increasing disquiet amongst parts of the judiciary that the whole exercise of assessing demeanour is not only futile but dangerous. Lord Leggatt, who was recently sworn into the Supreme Court, observed growing scientific evidence that ordinary people cannot make effective use of demeanour in deciding whether or not to believe a witness. While he was still sitting in the Court of Appeal, he sat in a case in which it had been argued that the delay between the judge seeing a witness and the making of his final decision meant that the judge would have forgotten his appearance and demeanour. Lord Leggatt held that ‘to attach any significant weight to such impressions in assessing credibility risks making judgments which at best have no rational basis and at worst reflect conscious or unconscious biases and prejudices’.

Lord Leggatt’s words are increasingly being cited in more recent cases. Study after study supports the idea that ordinary people, even professionals such as police officers, are notably bad at using non-verbal cues to detect lies. A 2015 study is interesting for suggesting, however, that there may be far more reliable indicators of detecting lies than body language. In a study involving airport security officers, Professor Thomas Ormerod, a specialist in forensic psychology, found that his sample of officers could not simply identify travellers planted with false stories by attempting to look for ‘nervous’ body language. Concerningly, the attempt to do so resulted in the officers disproportionately targeting particular ethnic groups.

Ormerod did find, however, that older techniques such as examining small verifiable details in an individual’s story, or testing individuals by asking them to report an event out of sequence, were extremely effective means of lie detection. The methods that worked tended to focus on what we say rather than how we say it.

And yet, even controlled experiments find that a tiny minority of people do have an uncanny ability to

read people non-verbally. Law students are often told a story about Max Steuer, one of the best defence lawyers at the New York Bar in the first half of the 20th century. Then, as now, there was a cardinal rule for cross-examining witnesses: always ask closed ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions – really statements disguised as questions. The idea was to bounce your own narrative off the witness. The corollary was to never ask open questions: when, what, how, why. Never give the other side’s witness a chance to give their story. And above all else never let them repeat it.

In December 1911, Steuer was about to cross-examine Kate Alterman, a young immigrant survivor of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. The fire had killed 146 of her fellow garment workers. It was, at that time, the deadliest industrial disaster New York had seen and the owners of the factory were indicted on manslaughter charges. The public mood was ugly. The owners were accused of having locked the fire escapes, stopping the women and girls working in the factory from slipping out for smoking breaks. They hired Steuer.

Triangle Shirtwaist fire centennial commemoration in New York City, 25 March 2011. Photo by Artie04, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

Before her cross-examination, Alterman gives her evidence, explaining the consequences of the locked doors. She recounts her desperate attempt to flee the factory with a friend who collapsed and would not get up, her hair and dress beginning to burn. She describes seeing the manager’s brother Bernstein jumping around ‘like a wildcat’ just before he became engulfed in flames. She speaks of the crowds that were gathered around the locked doors, trying and failing to get out as the flames rose. When she finishes speaking there is absolute silence in the court room.

But Steuer sees or hears something in Alterman that no one else does. When he rises to question her, he breaks the cardinal rule. Instead of asking a short-focused question, he simply asks her to tell the court her story again.

After she finishes, Steuer asks her: ‘When Bernstein was jumping around, do you remember what that was like? Like a wildcat, wasn’t it?’

‘Like a wildcat’, she answers.

‘You left that out the second time’.

Even before he gets Alterman to recite her story a third time, it is obvious she has memorised a script. Steuer asks her when the prosecution taught it to her. The owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory were acquitted.

If you read the transcripts of Alterman’s testimony, they are a compelling record of tragedy – and not dissimilar from the testimony of any other witness from the trial. But plainly Steuer saw or heard something that is lost in the printed word. His story is often told to illustrate how the practice of law cannot always be distilled into rules, and how testimony is not just about what is said: at times there is something diaphanous which can lead us to the truth, sparkling just below the surface.

I am no longer so sure. Some say Alterman did learn a script, but not necessarily because she was lying. As a young and recent Polish immigrant, she was simply frightened of making a mistake in her second language.

Published 26 July 2021

Original in English

First published by New Humanist 2/2021

Contributed by New Humanist © Gayan Samarasinghe / New Humanist / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

A bill on Animal Welfare is currently making its way through the UK parliament. If passed, non-human vertebrates would be recognized as sentient. But would this mean that animals have the same or similar rights to humans?

In Poland, a weak democratic culture collides with unfamiliarity with the historical values of the European Union. Rebuilding the rule of law means explaining to citizens that the constitution is there to protect them. The alternative may be Polexit.