Our ancestors appear to have lived according to beliefs they considered irrefutable. All societies develop belief systems, or epistemes, which frame how we know ourselves and the world. Our nomadic ancestors turned to sympathetic magic, while in the millennium before Christ, religious devotion to deities developed.

It may seem, in our supposedly secular western world, that we have moved beyond belief in unassailable and all-encompassing epistemes. The power of science, it’s tempting to think, has liberated us from having to rely on such shaky, arbitrary truths. Yet to believe in the irrefutability of our own episteme would be pure vanity. Given what we know about humanity and its history, we must consider the possibility that the frame by which we currently measure and understand the world may appear, to future generations, just as absurd as the myths and rituals of the past tend to appear to the contemporary eye.

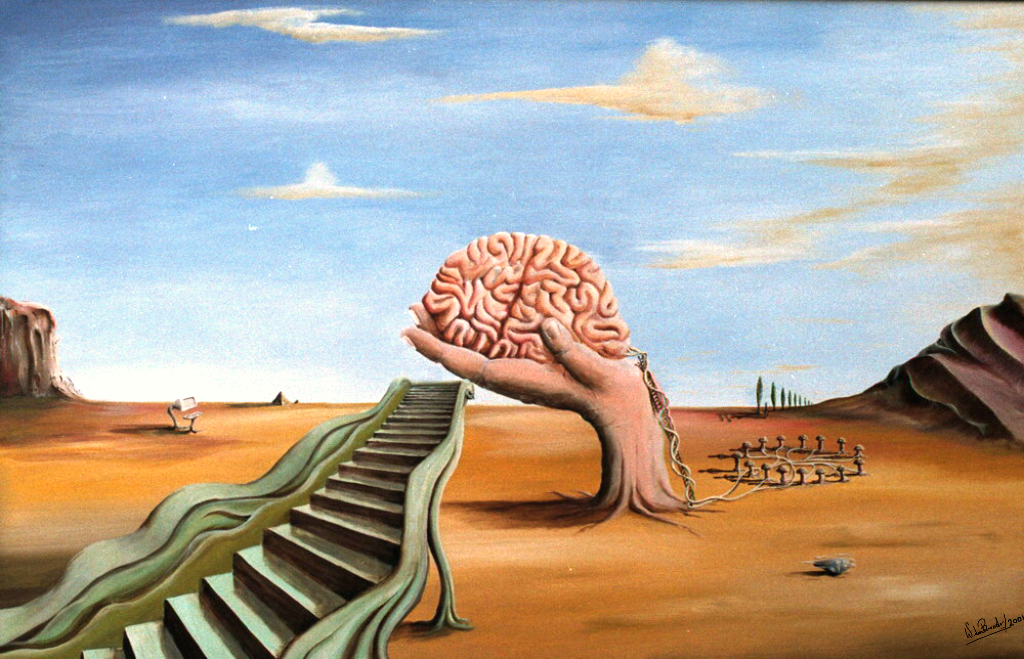

In fact, I believe that it is my own field of mind science that does for us today what religion once did for our ancestors. Nowadays, we turn to psychology to explain and assuage the doubts and conflicts that arise from our experience of the world. When we don’t understand our behaviours and habits, we may speak of psychological constructions: ‘thought patterns’, ‘chemical imbalances’, the ‘workings of the unconscious’ and so on. Yet, as I will argue, this adherence to psychology has all the markings of a new kind of superstition.

Auguries of our era

A good start, in attempting to understand the shape of our own episteme, is to learn from the belief systems of previous civilisations. The way these cultures put together symbols to ground their spiritual practices can often seem arbitrary, while their adherence to ritual often strikes us as excessive. Take the Pharaonic Egyptians and the practice of mummification – a highly elaborate process that could take the embalmers up to 70 days to complete. The ancient world abounds with such examples. In his Life of Marcellus, the historian Plutarch (c. 46-119) recounts the rites performed by the Romans preparing for battle:

(There is a) branch of the priesthood to which the law assigns as one of its most important functions the observation and study of auguries, which arise from the flight of birds … The Romans do not [usually] practice any barbarous or outlandish rites … nevertheless at the outbreak of this war they felt obliged to follow out certain oracular instructions laid down in the Sibylline Books, and to bury alive two Greeks, a man and a woman, and likewise two Gauls in the place known as the Cattle-market.

Plutarch is making a distinction between the bird auguries, which he seems to find reasonable, and the burying alive of the human sacrifices, which he associates with ‘outlandish rites’. From our vantage point today, both the bird auguries and the Sibylline books seem like incoherent pathways to truth, equally alien to us.

We struggle to get a grip on these Roman rites, in part because religion in the ancient world was not something one understood intellectually. It was something one felt or did – a matter of participation. Conversely, post-Enlightenment notions of religion focus more on the intellectual aspects of the relationship between man and the transcendental. This is part of the Protestant emphasis on religion as a rational system, by which even God is bound to the laws of nature.

This distinction is fundamental to how our own society in the 21st century conceives of truth. Our scientific age maintains the notion of a rational system of causes and effects, arising from nature. Yet we still reach for the emotional goal of belief: namely, the relief of doubt. Between science, religion and imagination, psychology now reigns where rational explanation runs out. Many of its practices – from education to medication to applied uses – have assuaged the suffering of millions of people. But it is also a field in which belief and emotions come together to satisfy our need for meaning and ritual.

Psychology is essentially the language game of our episteme. It reflects our desire to know in the prevalent language of explanation in our culture. Just like the Romans interpreted the flight of birds as revelations of what the future might hold, our language of interpretation draws from the sciences. Take how we describe the mind. We often talk about ‘processing information’ or ‘storing memories’. But the mind is not a computer; memories can’t be stuffed into it. In fact we don’t know exactly where our memories reside.

The way we talk about the brain seems like a solid interpretative language to us because it draws from the exalted stature of the sciences. Yet psychology is still a young science, trying to perfect its methods and discover the meaning behind its findings. While no branch of science can lay claim to the absolute truth, it is remarkable how tentative are the models used in the field of psychology. They are hardly as robust as those of chemistry and biology for even the most basic elements of the mind, like memory or dreams. Experiments are limited by the diversity of the populations tested. Furthermore, we have trouble replicating them and ensuring that lab tests are indicative of behaviour in the real world.

Nevertheless, speculative ideas in the field are often understood by the general public as established facts. The anxious urban human has developed a penchant for framing the world in ‘mental’ or ‘neural’ terms. We instinctively reach for the frame of psychology to understand the behaviour of animals, children, and even ourselves in the past. Symbols and concepts drawn from the psychological sciences – such as ‘conditioning’ or ‘dopamine bursts’ – are appealed to as if they provided causal explanations. This relies, in the first place, on the materialist assumption that the mind is the brain, even though in the field we consider the actual relationship between the two to be a subtle mystery.

Enlightenment or emotional needs?

Rather than an exact science, therefore, psychology today operates as a system of belief. This is not to dismiss the field entirely; it can be helpful. Take the efficacy of pharmaceutical drugs, like treating ADD with Adderall or general anxiety with Xanax. However, we have a very partial understanding of how and why these drugs work. Furthermore, the placebo effect demonstrates that at least half of the efficacy of many drugs results simply from belief in the clinical situation and the power of the medication.

And while therapy and pharmaceutical drugs are both employed today with significant success, they seem to rely on contradictory sets of beliefs. Therapy involves developing a notion of identity and agency through the participatory ritual of discourse, confirming the patient’s belief in their own individuality. The use of medication, on the other hand, confirms the belief that biology is the ultimate locus of our suffering.

Ideally, mental health treatment allows for both individual dignity and the direct modulation of well-understood mechanical aspects of the brain. But even these two methods together do not capture all the aspects that could contribute to mental health. They leave out, for example, sociocultural context and the gut-brain microbiome.

Using psychology to explain ourselves is simply the 21st century’s superstition of choice. Thus, psychology presents a secular pantheon, host to the druids of the pharmaceutical and brain imaging professions, along with the magicians of the unconscious. Our culture is not so different, then, from those of the ancient world. The charismatic leadership of big chiefs and shamans has been diffused into a trust in scientific and technological achievements, which work well enough to be believed in.

We are often told that superstition refers to those beliefs or practices which are inconsistent with the degree of enlightenment reached by the community. But what if they were consistent not with the enlightenment of a community, but rather with its emotional needs?

Plutarch considered superstition to be an emotion engendered by false reasoning in men who were ‘too weak’ to be atheists and thus pitifully appease the gods day after day in lives replete with fear and trembling.

…the ridiculous actions and emotions of superstition, its words and gestures, magic charms and spells, rushing about or beating drums, impure purifications and dirty sanctifications, barbarous and outlandish penances and mortifications at the shrine – all these give occasion to some to say that it were better there should be no gods at all than gods who accept with pleasure such forms of worship, and are so overbearing, so petty, and so easily offended.

The process by which a person becomes superstitious seems directly tied to their sense of vulnerability. We respond to vulnerability with beliefs and actions that instil a feeling of control and protect our sense of self-worth. The mechanism of superstition may therefore be the active search for answers (however illusory) in times of stress and fear. As observed in the actions of traditionally superstitious people – like athletes, gamblers, sailors, soldiers, miners, investors and college students – humans seem to need to engage in rituals to cope with high-stress situations that have highly uncertain outcomes.

Spinoza notes how false prophets benefit from this sense of doubt, and gain in popularity during perilous times. Historical examples abound. During the months leading up to the invasion of Tuscany by King Charles VIII, a charismatic Dominican preacher, Girolamo Savonarola, channelled the anxieties of Florentines in his firebrand sermons. His prophecies of a divine scourge and a Christian renewal entranced the city. More recently, consider the revived popularity of astrology in our own times of pandemic and climate crisis.

From belief to action

Superstition is not only a matter of belief, it also produces a particular set of behaviours. In 1741, David Hume wrote it was not only fear, but also weakness, ignorance and melancholy that bring about superstitious behaviour. The terror and apprehension of facing adversity can be appeased by ceremonies, observances, sacrifices, presents and mortifications. A sort of slavery thus develops in the superstitious man wherein he is domesticated to pray to deities in a hundred private ceremonies.

In Hume’s time, these rituals revolved around the Christian church. In Plutarch’s, they involved animal sacrifices and the consultation of oracles. Today, we are more likely to pound the proverbial drum by consulting doctors and therapists, or purchasing popular psychology books. We still depend on ‘experts,’ periodically sacrifice our pleasures, and follow detailed scripted behaviours in our social rituals. Compare the use of ancient magic charms, for example, to our allegiance to technological totems like the internet, or our healthy diets and herbal supplements to ritual purifications.

We might also see the urge to perform penances and mortifications manifesting today in the deep sense of doubt and guilt that abounds in liberal society. And let us not overlook the catharsis pursued in our continued reliance on art, drugs and experiences of transcendence at quasi-Dionysian cultural festivals.

Rituals are effective ways to counter doubt and confusion with action. According to ethologist Gordon Burghardt, they arise when two or more motivations are competing. When in a state of crisis, an individual is likely to have competing motivations for doing something and doing nothing. Engaging in a ritual is thus a way to displace and redirect anxious energy towards some focal point. When one fails to perform a step of the script-like sequence of ritual behaviour, one experiences anxiety. This may have to do with the relief provided by satisfying a compulsion; it may also be related to the invigorating creative element of ritualised repetition.

Society today is attracted to superstitious belief and ritual practice, in much the same way as our ancestors were. Despite the power invested in its scientific pretensions, psychology is one of our contemporary forms of superstition, donning a lab coat to cover up its magic amulets. It offers a language through which to interpret human behaviour. It helps us to gain an emotional, rational and linguistic grasp on our experience.

That is not all it is able to do, as we have explored. But there is an ambivalence at the heart of the discipline. We use its language every day, while not at all taking into account that we are placing a cultural frame upon the unknown. Occupying a realm between wild thought and causality, between belief and emotion, psychology is indeed a suspicious science. Future generations may say we were fools to render it such significance. But our civilisation’s search for answers, and the longing of individuals to ease their anxiety, will be all too familiar.