The urgency of the climate crisis demands individual ethics as much as a willingness to cooperate with power. But reconnecting humans with the natural world also forces us to revisit the promises of ever-growing efficiency and a culture of exploitation.

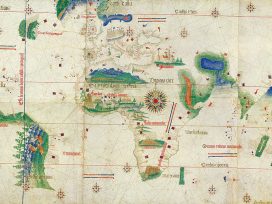

The legacy of racism and colonization on the climate crisis is rarely addressed. From the 15th century onward, the West’s relationship to the Earth has been characterized by ‘colonial habitation’: ‘a violent way of inhabiting the earth, subjugating lands, humans, and non-humans to the desires of the colonizer’, sayes Malcom Ferdinand.

After subjugating peoples and exploiting natural resources, western-centric colonial thought now proposes purely technical and technocratic solutions to the climate crisis it has created. What we need instead, Ferdinand tells in conversation with Aurore Chaillou and Louise Roublin, is ‘changing the way lands are inhabited’ by bridging the divide between decolonization and environmentalism.

In Australia, the domination of nature has gone hand in hand with the dispossession and violent assimilation of native populations since the very first arrival of European explorers in 1770. The ever-growing coal mining industry explains why the country has the largest per capita greenhouse emissions in the western world. Meanwhile, lobbying has fed misperceptions and created a false dichotomy between the environment and the economy.

Peter Salmon on Australia’s regressive impact on the global fight against climate change.

One way of decolonizing the fight for climate justice is taking power away from lobbies and inconclusive high-level conferences, and granting rights and representation to all those involved – including marginalized communities, animals, and inanimate natural entities.

In 2017, the Maori community in New Zealand has been acknowledged as the legal representative of the Whanganui River, and India has recognized the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers as ‘living entities having the status of a legal person’. Granting rights to all nature and equipping it with ‘phonation devices’ – Damien De Blic argues, drawing on the thoughts of Bruno Latour – can help bridge the gap between civilization and the natural world.

On virtues and pragmatism

Pope Gregory I, in office during the ecological upheavals of the 6th-7th century, was convinced that humanity was being punished for trespassing ethical and ecological boundaries. The Late Antique Little Ice Age is under many respects antithetical to the Anthropocene, but it provoked similar consequences – starvation and epidemics, the collapse of economies, migration vawes – and ignited a climate anxiety like the one we are experiencing now.

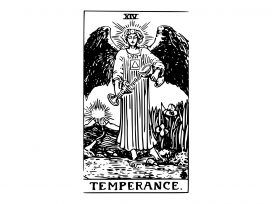

Pope Gregory was convinced that only temperance, a virtue now fallen into disuse, could rescue humanity. ‘Virtue ethics provided a guide to a good life, in all aspects of the word, implanting above all else the ideal that each individual existence was intertwined with multiple other beings’, writes Matilda Amundsen Bergström.

Temperance

Virtue overcoming boundaries

From virtue ethics to the pragmatism of political action: activist Will McCallum calls for constructive cooperation when dealing with climate policy. The urgency of the situation demands that we set aside culture wars and help those in power take action, whether we agree with their broader politics or not.

‘Instead of motivating people to act fast, the highly charged public debate is at risk of slipping into divisions based on political ideology. Policies and technological progress are judged on the basis of provenance, rather than their potential for tangible impact’, argues McCallum. Hysterics are of no help at a time of crisis.

Hysterics do not help in crisis

How to transcend the climate change culture war

There’s cloud and Cloud

When a data center caught fire in Strasbourg on 9 March, a thick cloud of smoke rose over the city. It reminded us of the materiality of the other cloud, where our data is stored.

Since the ‘70s, the progressive miniaturization of technological devices has gradually ‘diverted the mind from the gigantic industry that consumes vast amounts of material resources, and the working conditions of the labour force supplying the industry with these resources’, writes Christina Gratorp.

While ‘technology as a public good is the political gospel of the day’ as the European Union has made digitization a pillar of its Next Generation EU fund, a critical discussion is needed about the pressing environmental and humanitarian aspects of technological development.

The materiality of the cloud

On the hard conditions of soft digitization

Ten years after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Japan has announced its plan to gradually release into the Pacific the treated contaminated water used to cool down the damaged reactors. Recalling the events of 2011, Masatake Shinohara reflects on the power natural disasters have to blur the distinction between the human and the natural world: ‘At the moment of the disaster, we realize that the society of the spectacle is not solid at all. It becomes apparent that it is in sustained contact with times and spaces that exceed any human presence’.

Notes from underground

A challenging urban gardening experiment on soil ‘as nutritional as carpet’ gets Kate Brown thinking of the history of humanity and civilization as indissolubly tied to the history of the underground world.

‘Microbial life under our feet works in concert with insects, worms, plant roots and fungal arteries to create a living world of creativity and mastery, one which scientists are just beginning to grasp’.

Mariana Verbovska offers grim snapshots of the ongoing effects of climate change on Ukraine’s natural landscapes: lakes and wetland suddenly drying up; crops destroyed by droughts; seasons losing their meaning; and sea levels set to rise significantly over the next decades, jeopardizing Europe’s longest coastline.

Walk on water

Climate change and life in Ukraine

Before it was hot

The Anthropocene is now under the lens, but contributors to Eurozine’s partner journals have been covering climate change issues long before they became hot news items – and they still offer important perspectives for today’s reader. Here’s a selection from our archive.

How climate changes humans

Contrasting reads from the Eurozine archive

Published 22 April 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Myths of landscape

O’r Pedwar Gwynt 1/2023

The rewilding controversy: challenging the restorative myth without ignoring agriculture’s environmental record. Also: history and sex education in the new Welsh school syllabus.

How democracies transform, fast and slow

A response to John Keane

For all its acuity, John Keane’s theory of democide risks confusing democratic degradation with a transformation of the political debate. Not only that, it fails to account for the radicalization of authoritarian systems once democracy has been killed.