Just landed in Moscow after recovering from the Novichok poisoning of last August, Putin’s major political opponent Aleksej Navalny was immediately arrested. This selection of Eurozine reads helps understand why the Kremlin fears him and is cracking down on niches of free expression and rising civic activism.

In reconstructing the dynamics of Navalny’s poisoning on August 20, Bellingcat’s work played a crucial role. In collaboration with The Insider, the open source investigative collective discovered that FSB agents regularly followed Navalny’s movements, including in Tomsk last summer. Even in the face of the evidence, the Kremlin continued to deny any involvement.

Aleksei Navalny photographed in a Moscow street after a zelyonka attack. Photo by Evgeny Feldman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In an interview with Eurozine editor Simon Garnett, Bellingcat founder Elliot Higgins talks about the shooting down of MH17 and the use of chemical weapons in Syria, two previous occasions in which the Kremlin had set in motion its disinformation machine.

Old escapism, new activism

The idealism and enthusiasm characterizing Russian media in the early post-Soviet era did not last long: under Putin’s presidency, ‘important media assets ended up securely under the control of trusted loyalists’. The coming-of-age of a tech-savvy generation posed new challenges to established media capture tactics, and the Kremlin responded with greater police violence and incarceration of political opponents.

Navalny, who has been exposing corruption at high levels of government through his FBK (Anti-Corruption Fund) collecting millions of online viewers, has spent 180 days under administrative arrest in 2017-2018 alone. Yet the Russian media landscape shows a rise in civic activism and a promising new vibrancy, Maria Lipman writes.

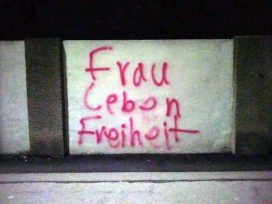

Free expression on the margins

The Kremlin and the media

Since the early 2000s, the Russian ‘net culture’ has been apolitical and escapist. ‘By the end of the first decade of the new millennium, the most culturally and economically active part of Russian society was completely unprepared for any kind of political participation. […] The new Russian opposition grasped the problem and Aleksej Navalny was the one who thought he found a solution’.

A nationalist with a past in the democratic and socialist party Yabloko, from which he had been expelled for his xenophobic views, Navalny soon became the most popular muckraker in Russia. ‘He wanted to show Russians that they could fight corruption from the convenience of their living rooms’.

Andrei Soldatov on the evolution of online political activism in Russia, from the opposition to the military to an army… of trolls.

Paradoxes of participation

Democracy and the internet in Russia

Staged opposition

Monopolized by the government, the Russian TV industry shaped a society of pure spectacle, and rendered any opposition absurd from the inside. But the matrix of managed democracy underpinning Russia’s postmodern dictatorship has some cracks on its surface.

‘In twenty-first-century Russia you are allowed to say anything you want as long as you don’t follow the corruption trail’, wrote Peter Pomerantsev in 2013. With his ‘playground sense of righteous anger’, Aleksej Navalny ventured into a dangerous ground for the Kremlin.

Unlike in Ukraine and the Baltics, where music played a significant role in post-communist social protests, in Russia the authorities ‘are not only in charge within the official media, they also control the protest sphere’.

Wojciech Siegień explains why no Russian revolution will come from the stage.

Protests compared

Putin stepped up his efforts to crack down on the opposition in the aftermath of the 2011 mass street protests. Volha Biziukova compares those revolts with last year’s anti-Lukashenka protests in Belarus, finding similarities but also a fundamental difference: a ‘sense of representing and acting on behalf of the majority of society is the key difference between the protesters today in Belarus and those in Russia in 2011-2012’.

Further Eurozine reads on the Belarusian revolution – and the game Russia is playing in Minsk – can be found here.

This article is part of our series of thematic reading lists. Check out our other Topicals here.

Published 22 January 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Memory as source of personal and collective resistance: on Yuri Dmitriev’s effort to document the history of the Mordovian GULAG while himself imprisoned in one of the penal colonies in the region, by a member of the Memorial Society.

Full steam ahead

Russian propaganda running up to the Polish elections

Ranging from influencers to opinion leaders and self-proclaimed experts, pro-Russian communities are consolidating in Poland. The Russian Federation not only supports these groups through the Polish-language sources it runs, but also has an influence on the activity of some of the people operating within them.