Memory as source of personal and collective resistance: on Yuri Dmitriev’s effort to document the history of the Mordovian GULAG while himself imprisoned in one of the penal colonies in the region, by a member of the Memorial Society.

Concerned to avert a ‘singing revolution’ in Russia, the Kremlin has co-opted the country’s independent music scene. Apolitical and nihilistic, it is doubtful whether Russian artists could ever play the same role as their Ukrainian counterparts on the Maidan. The group Shortparis is a notable exception – for now.

Analyses of revolutions in post-communist countries have neglected the role played by culture. Even the fact that the main social protests in the post-Soviet states were named after colours, or flowers, is telling. In Ukraine there was the Orange Revolution in the winter of 2004/2005, while in Belarus, in 2005, there was the denim protest, which was also known as the Cornflower Revolution. In the same year, there was the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, while in Georgia there was the revolution of roses two years earlier.

It is likely that the inspiration to name protests after flowers or other symbols came from Portugal’s Carnation Revolution in 1974. The protest against the Estado Novo regime started with the song Grândola, Vila Morena – another similarity between the coup against Marcello Caetano and the revolutionary experiences of eastern Europe. They were not only colour revolutions, but also musical ones.

The role played by music in social protests in post-communist states was most visible in the Baltics and Ukraine. The former – a region of countries with deep folk music traditions – had a four-year long resistance movement, called the Singing Revolution, between 1987 and 1991. Ukraine’s Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity were also known for their music. In 2003 the protesters at the Maidan were energised by the song Razom Nas bohato, nas ne podolaty (‘Together we are plenty, we will not be defeated’), performed by Greenjolly. During the cold winter of 2013/2014, activists listening to Plyve kacha (‘A duckling is swimming’), a folk song dramatically performed by Pikardiyska Tertsya at the funeral of the Heavenly Hundred. Popular among the protesters were the powerful riffs of the Belarusian band, Brutto, with their recording of Voiny sveta (‘Warriors of Light’).

These experiences show that anti-authoritarian protests need more than a community of likeminded people, defined tasks and clear leadership. They also have to include cultural elements, with emblems and symbols that unite people. In the process of mobilisation and resistance, the creation of music is not just in the background, it also carries great potential for action. The power of music is well known to authoritarian regimes. To neutralise it, they start by taking over its distribution. Putin’s Russia is no different in this regard. With the deteriorating economy in the last few years, the threat coming from youth sub-cultures has become a real challenge to the authorities. Now the government’s priority is to get any unsubordinated segments of society under its control.

Overall the Russian music scene has a quite clear picture. On the one hand, there are the so-called dinosaurs of the stage. These are artists who are omnipresent on state television. Through this medium they feed viewers with an inconceivable amount of musical kitsch – presented as sophisticated art. The last presidential elections demonstrated how valuable these ‘government-sanctioned’ artists are to the regime and how much they are willing to pay it back for some air time. As a result of the alliance with authorities, a number of famous artists even ‘spontaneously’ posted pro-Putin content during the campaign and used social media to encourage people to vote. There were some overly enthusiastic singers who made music videos praising the regime.

On the other hand, there is a new independent music scene which has emerged unexpectedly for the Kremlin. This scene is made up of artists who combine hip-hop and experimental electronic music. The majority of them do not openly criticise the regime, nor do they encourage protests or support opposition leader, Alexei Navalny. They either focus on conceptual art or real problems of the Russian youth. Nevertheless, the authorities have become interested in their activities and many concerts have been cancelled. This was the case with Husky, a popular rapper whose concerts were cancelled throughout Russia in 2018. Eventually, the singer was arrested for destroying property and not following police instructions. The avalanche of repression started soon afterwards.

An alternative electronic group, IC3PEAK, was also banned from performing. As was the pop-punk group, Frendzona, and the hip-hop performers, Face and LJ. In addition to the arrests, local authorities set up expert commissions and counsels which claimed that the music of the arrested artists had a negative influence on the youth and was leading to drug use and suicides.

As expected, information about the repression reached the federal level. The regime panicked and initiated a series of ridiculous responses to quell the ‘crisis’. Typically for top-down authoritarian structures, a decision was made to include independent culture within the centralised system that would offer grants to hip-hop artists. With such support they could rap about the positive things in life. The level of absurdity worsened when Dmitry Kiselyov, the main propagandist of the Kremlin, rapped the poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky in an attempt to show that he is the number one Russian rapper.

Russian rapper Basta on stage. Photo by Alina Platonova from Wikimedia Commons

Yet the picture of Russia’s polarised music scene is far from the truth. To think that there is a clear division between the mainstream and independent scene is a simplification. The difference between the two worlds is not only blurred but also controlled by the authorities. The rapper Husky is the best example of this semantic confusion. Not many people remember that even though today repressed by the authorities, Husky supported Russian mercenaries in Ukraine’s Donbas and held concerts in the occupied territories. He was accompanied by Zakhar Prilepin, another Russian artist who joined the Kremlin’s propaganda war against Kyiv.

The changing of roles – from propagandist to victim (or the other way around) – is one example of the chaos orchestrated by the Kremlin. The Russian authorities are not only in charge within the official media, they also control the protest sphere. Think again about Husky and the fact that after his arrest several big names within the Russian hip-hop scene supported him, including Basta, Oxxxymiron and Noize MC. They were allowed to organise a spontaneous concert in Husky’s support, which was broadcast by the TV channel Dozhd. The artists who participated in the concert shouted slogans from the stage such as: ‘I will sing my music’. The authorities, by allowing them to do this, have showed they have come to terms with the fact that the audience, especially the youth, have reached a high level of pressure that needed to be released. For this reason, a group of pop stars were used to hinder a large protest action.

The rapper Basta (Vasili Vakulenko), who is the true godfather of Russian hip-hop and hailing from Rostov, was until recently viewed as the embodiment of Russian alternative music. However, in an authoritarian state, the commercial success of a music genre usually results in its monopolisation by the authorities. Even though Vakulenko was respected by the Russian youth not so long ago for his melodic protest songs, in which he criticised the state structures, he could not remain an independent artist. First he was offered the position as a juror in a musical talent show, naturally one that is aired by the state TV channel. Not long afterwards in an interview he supported the unpopular pension reforms. After he received a massive wave of criticism, including accusations of being a sell-out, he backtracked and apologised to his fans. Basta’s example shows how someone who was once considered a voice of the youth resistance can yield to the pressure of Kremlin officials. Basta is one of Russia’s many corrupted artists. He is, to some extent, now broken, fighting to retain the image of an independent artist.

IC3PEAK backstage during a rally against the isolation of Runet. Photo by Simon Krassotkin from Wikimedia Commons

As mentioned above, the Russian authorities fully control protests. Therefore, the regime also determines who has no right to oppose and in whose defence a concert can be organised. This was the case with IC3PEAK. When Basta and Oxxxymiron were defending Husky, IC3PEAK was pulled off the stage and its group members detained by the police. Only because of their massive popularity, they would not have received any support from their musical elders. The fact that IC3PEAK still performs is thanks to their own effort and their many fans: IC3PEAK has a record with over 28 million online listens. Recent protests against the government’s efforts to limit online freedom have also shown how the opposition is trying to win the voice of the musicians. IC3PEAK performed during the demonstrations where they played their hit song Smerti bolshe nyet (‘Death no more’).

IC3PEAK shows the qualitative difference between today’s protest culture in Russia and the colour revolutions in other post-Soviet states. While protesters of the Orange Maidan in Kyiv were collectively chanting ‘Together we are many, we cannot be defeated’, IC3PEAK’s lyrics are put to the backdrop of synth sounds: ‘Let it all burn. Death is no more.’ Singing about revolutions formed a symbolic community that made references to brotherhood and togetherness, even if it was togetherness in grief – as was the case with the Revolution of Dignity. Yet such promises are not found among the voices of young Russian artists. Their songs are rather empty, without the power that unifying symbols have. If they were to become songs of a revolution, it would be a nihilistic revolution – probably similar to the Bolshevik one.

Despite all this, there are still unique artists in Russia who have great protest potential. This includes a group from St Petersburg called Shortparis. They have been around for only a few years, yet their music videos have recently gained huge popularity on the internet. Just two days after Shortparis’s hit songs, Strashno (‘Dreadful’) and Styd (‘Shame’), were released online, almost three million views were recorded.

The music video for Strashno shows a group of young people with shaved heads entering a school and passing horrified students in the hallway. They enter the gymnasium where a group of terrified people with ‘migrant features’ – as they say in today’s Russia – have gathered on the floor. The sweatshirts of the intruders have what seems to be Arabic writing. Quite unexpectedly, the whole scene turns into some kind of musical. Theatre curtains, carpets and choreographed dances appear. The last scene is probably the most powerful: a group of people trudging through the mud and tall grass towards an unknown destination. They are carrying a boy with a Russian flag on a procession float. Grey blocks of flats are in the background to Shortparis singing ‘eternal and honest’.

The lyrics, combined with the story of the music video, are, in my view, one of the more interesting diagnoses of the social situation in Russia. Together, they could be regarded as portraits of the symbols of the Russian collective imagination which could be interpreted as the triggers of hidden, traumatic content. In the lyrics, you can hear words like ‘school’, ‘immigrants’, ‘gymnasium’, ‘major’, ‘Kalashnikov’, ‘ice’ and ‘housing estate’. There is a child with a flag, an image of Arabic letters and a young man with a bag in front of a school. This all releases a sequence of pictures linked with suppressed traumas: the terror attacks in Bieslan and Kerch, the Chechen war, the Caucasus, state violence, militarisation, futility of resistance, conformism and indifference. The song title Strashno is also a key word, according to the artists themselves. It defines the atmosphere in today’s Russia. It is a feeling of endangerment, an undefined fear that hangs over Russia. The musicians admit that the track is based on what they have captured from pieces of conversation around them.

Shortparis’s work is troublesome for the authorities because their ingenious combination of images resonates with the collective imagination. It is also difficult to censor because what they present has more to do with a sense of feeling than what can be explained with words. It might turn out to be the best template as how to create a strategy for resisting the growing authoritarianism of Putin.

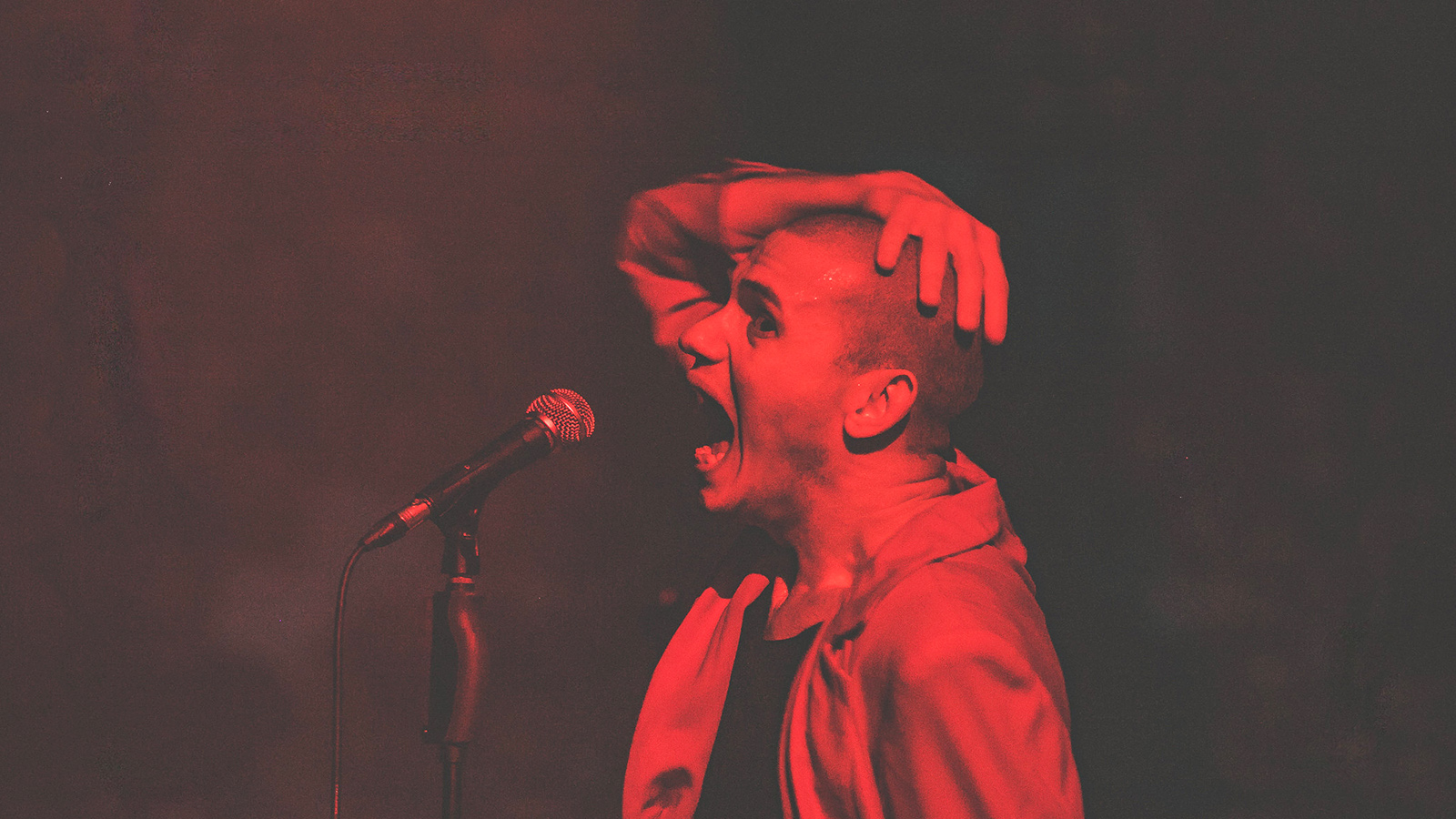

Shortparis. Photo by Oli Zitch on Flickr

The example of Shortparis also suggests something else. The Kremlin has an ability to quickly and efficiently change strategy in order to neutralise what it regards as a threat. Early this year after their huge online success, Shortparis was invited to a popular late night talk show called Vecherniy Urgant (‘Evening Urgant’). They performed a live version of Strashno. Interpreting the fan reaction, one gets the impression that an underground band, critical of the regime, broke into the mainstream via federal television. The host, Ivan Urgant, showed great bravery by inviting them to the programme.

Yet taking a closer look at the choreography, this may not actually be the case. Towards the end of the performance, when the band was dramatically repeating the phrase ‘That’s why it’s dreadful!’, a group of younger extras entered the front of the stage. They are perfectly styled to look like the lead singer. They were bald and dressed in reflective yellow vests, moving around, making terrifying faces and repeating the word ‘dreadful’. This small change in the choreography changed the meaning of the whole song.

The programme’s YouTube channel has 3.2 million subscribers, and for online viewers Strashno became a song warning about the chaos of the French Yellow Vest (Gilets jaunes) protests. As a result, a song that was critical of Russia, in the final moments of Urgant’s programme, blended with the Kremlin’s narrative of the rotten West. Millions of Russian viewers from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok understood the performance as a version of Putin’s warnings: ‘Do you want it to be like Paris over here?’

The Russian authorities are wiser after numerous colour revolutions in the post-Soviet states. They have long been working on a new arsenal of measures capable of halting events that could lead to widespread social protests. The amount of measures they could use against critical artists, with a potential to mobilise crowds, is impressive. Apart from an apparatus directed at repressing disloyal artists, they also use systems based on clientelism, corruption and allow fake protests. The most subtle form of confrontation is in the sphere of symbols. The example of Shortparis shows that the Kremlin has the potential to redefine the context of artistic creation. Like a magical fairytale where white becomes black and the enemy turns into an ally, the oppressor becomes the liberator. If a revolution happens in Russia, it will not be a singing one.

Published 8 October 2019

Original in English

Translated by

Daniel Gleichgewicht

First published by New Eastern Europe 5/2019

Contributed by New Eastern Europe © Wojciech Siegień / New Eastern Europe / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Memory as source of personal and collective resistance: on Yuri Dmitriev’s effort to document the history of the Mordovian GULAG while himself imprisoned in one of the penal colonies in the region, by a member of the Memorial Society.

Ranging from influencers to opinion leaders and self-proclaimed experts, pro-Russian communities are consolidating in Poland. The Russian Federation not only supports these groups through the Polish-language sources it runs, but also has an influence on the activity of some of the people operating within them.