As a young child, the only curse I knew about was from the Disney classic with its happy ending: the one where a kiss transforms the frog back into a prince, breaking the spell. It’s the kind of curse that has a cure, an end. I didn’t then know I would grow up experiencing the most painful curse: that of being born in the Middle East, a surviving, Arab Muslim Syrian.

From childhood, I also recall Jim Carrey’s speech on dreams and ambitions: successful people are those who believe that whatever happens in life happens for them, he said. I don’t believe this is the case for Syrians. In my country, life, war and natural disasters happen to us and not for us. Everything that happens only seems to multiply our pain and trauma. We haven’t experienced a break from atrocities for more than a decade now. In my country, we are used to not being seen as a population, which increases the damage. We are collectively traumatized.

We are used to the smell of death – yes, death does have a smell and it lingers.

Fleeing war

I was 18 years old when the war started and first experienced survival guilt. I still remember the day I woke up to the sounds of an explosion near my home. Living in a military neighbourhood made us a direct target for ISIS and terrorist attacks. The explosion that day turned out to be the assassination of a colonel in the Syrian army. They had bombed his car in the street across from my house. It was nothing but ruthless. I remember going to college that day carrying my fears with me, worrying that they might kill my dad any day. All I could think of was ‘will my dad be safe’ and ‘when will it be my turn to die’.

My dad was in the army back then and threatened by ISIS. They intended to kill him and his family. We survived by leaving him back in Aleppo and boarding a plane with twenty dead martyrs, who had been left out in the woods for more than ten days. I can still remember the smell of the bodies and the faces of those around me. They were terrified. Babies were crying. I still remember the aching goodbye we had with my dad. We didn’t know if we would ever see him again. I really wish my first flight had been less traumatic.

Displacement trauma

And I wish the curse had stopped there. But the world is not a fairytale. After we landed safely in my original home city of Lattakia, I knelt down and kissed the ground, sobbing nonstop. But my relief was short lived. I was lonely: I had no friends, no community and was bullied throughout my university years while coping with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

I remember when I first started having fainting episodes. It started back in our house in Aleppo. It was one of those calm, hot summer nights. My dad was on a night shift at his military office, leaving my mom, siblings and I alone at home. We would have witnessed a few riots and clashes here and there as the war was kicking off, but none of it was as dangerous as that night. We used to open the windows to allow a breeze into the house; Aleppo is known for its hot summers. We were minding our own business when a group of Jihadi people suddenly appeared from what seemed like the middle of nowhere and started yelling ‘Allahu Akbar’ in the streets while approaching our building with guns and rifles. They were shooting into the air. We had never seen or heard anything like it before. We quickly ran to shut the wooden shutters and balcony door. My mum immediately gathered us together and took us into her bedroom, the safest place in the house. I remember hearing the heavy shooting approaching us and my mother’s voice trying to keep me awake and on my feet. I would have fainted completely that day had it been for her voice. She held me tight while I sobbed nonstop.

That night might have passed, but the trauma would continue. I would nearly faint every time I heard a gunshot. When we were safe in Lattakia, after leaving my dad behind, I still had difficulties sleeping, even with soothing music – the only ‘music’ I knew back then was the sound of bombings and gunshots.

Living away from my dad for more than nine years made life as a teenager even harder. What I would call existential and regional migration has left me scarred for life. Being raised between two cities had already created some angst. I was looking for a sense of belonging to the community I was in but always felt like an outcast. I was neither Lattakian nor Aleppian but rather a mix of both and no one seemed to understand that. Having to leave Aleppo and my previous life behind made things even worse. I was the ‘outsider’ once again, this time in my birth city and without my dad’s stabilizing presence.

I had to overcome my PTSD on my own. Mental health issues were considered a taboo back then in Syria and my family didn’t acknowledge my disorder. I had no access to mental health support. My body seemed to ‘keep the score’. None of this landed well.

But I was not alone, of course. Millions of Syrians were displaced. Almost all my friends migrated to different parts of the world and had to seek shelter from the war. While many migrated to Germany and other European countries, others moved to neighbouring Arab countries like Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. Those who in desperation left by boat often drowned at sea.

The curse didn’t lift. The Syrian economy was collapsing; merchants, businessmen and bright minds had left, leaving factories and businesses in disuse. Sanctions on Syria due to the war contributed to weaken public health services. When the COVID-19 pandemic occurred, it posed a further threat to mental and physical health; hospitals had already been damaged and there was no access to proper treatment.

Earthquake and reliving trauma

Despite all this upheaval, I was naive enough to believe that our curse had been broken. I thought that we had had our fair share of pain and death for over twelve years. I thought that nothing worse could ever happen. I thought that I could dream once more, that I could lead my life no longer in survival mode.

But all my hopes were crushed when I woke up to the earthquake wrecking my house. Lying in bed, I first woke to the sound of rain hitting my window. It was pouring down and there was a thunderstorm as well. Then, I started hearing the earth rumbling. It sounded like rocks rolling down from the top of a mountain. The sound started to get louder as the building started to shake.

When I got up, all I cared about was finding my family. I woke my parents and siblings. We gathered in one place next to one the pillars of the house. Looking at my family’s faces, I was grateful this time that, if we were to die, we would all be together. We would not be separated like all those years ago. I felt that I could die in peace having my family around me, especially my dad. Seeing him standing there with us and protecting us sent me back to the tough times when he faced death during the war. We had to wait for him to contact us; he was in charge of one of the most important weapons depositories in Aleppo when ISIS broke into the building and started killing soldiers. We prayed nonstop for him. I do believe that our prayers alongside his good deeds and courageous heart are what saved him. He was back home safe and sound. Seeing him standing there, I felt safe.

As the earthquake started to get stronger, we began reciting verses that Muslims usually say when welcoming death. I thought I could never survive such a deadly earthquake and that was okay – I was with my family, which mattered the most.

But I survived once more. For a moment, I wish I hadn’t. Minutes after the earthquake had stopped, we had to collect our basic things and evacuate the building. My PTSD had been triggered. I started to panic and cry as my mind raced back to our house in Aleppo – the one I would never be able to go back to. It took me back to our car ride with ISIS surrounding the place, trying to reach the airport, to survive.

Aftershocks continued for a month. Each one would have the same effect: I relived my painful wartime survival experience over and over again. I didn’t know how to navigate life anymore.

What made it worse was the feeling of guilt. During and directly after the war, I was younger and didn’t fully understand the nature of my feelings. After surviving the earthquake, however, besides reliving my trauma, I knew I was experiencing compound survival guilt. I kept asking myself questions. Why am I still alive? Why have babies died and I’m still here? How come I still have a roof over my head, sheltering me, while others have ended up on the streets? Why? I kept feeling guilty for still being alive. How am I supposed to move on and not feel shameful for doing so?

How am I supposed to carry on with the smell of death filling the air around me? How am I supposed to sleep while the dreams of others were crushed under rubble? How can I feel safe and sound in my house while others are unsafe on the streets or forced to sleep in cold shelters?

How can we break this curse? Will it ever cease? Will the Syrian nation ever know what safety means? Will we be able to find a home away from disasters and wars, all brutality?

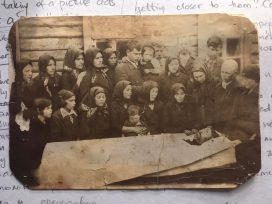

Aleppo after earthquake in February 2023. Image by Salem Mohammadi via Wikimedia Commons

Collective hope

I might not know the answer to all of this, but I know that being born Syrian is being born into a collective trauma that will linger as long as we hold onto it. Nothing we go through can be classified as normal. From the war, inflation and the pandemic to a deadly earthquake, survival guilt has become every Syrian’s shadow be it in the diaspora or at home. We either die or are haunted by those who are dead.

Whereas this may be every Syrian’s situation, I know that the Syrian love of life and homeland will equally never be eradicated. Compassion, generosity, patience, resilience and ambition will live on.

As the guilty survivor, social activist and Syrian citizen I am, I will continue to live, using my voice to speak up for all Syrians. The curse might never cease, but we will find ways to overcome it, to dream, to rebuild, to hope, to love, over and over again. We will find ways to turn our curse and pain into a source of wisdom.

The smell of death might have been strong for the past twelve years, but I know that the Syrian survivors’ love for each other after the earthquake is stronger than any pain. Blossoming roses in the gardens of Syrian houses and public parks announcing the arrival of spring are what fills the air now – the smell of new beginnings, the smell of love. We might not know what life has in store for us, but we do know that love can eventually cure all wounds and may just break all curses.