Source of resistance

Ukrainian arts shed light on a country that for decades has been ignored, repressed and treated as part of Russia. Culture in Ukraine must continue to be practiced and discussed, not despite war but because of it, write the editors of ‘Osteuropa’.

Can we discuss Ukrainian literature when the country is at war, when men and women are risking their lives to defend their freedom? Is it not tasteless to concern ourselves with Ukrainian film when forensic scientists are discovering mass graves in the regions formerly occupied by Putin’s marauders? Bucha, Izium, Olenvika, Balakliia… These sites of horror have been stamped into Europe’s collective memory. With every passing month, the list of names gets longer. The evidence of torture, rape, execution of civilians and other war crimes is overwhelming. Under such circumstances, is it not improper to turn our attention to the arts?

During the First World War, the art historian Wilhelm von Bode coined the phrase Inter arma silent musae (‘in times of war the muses are silent’). He was referring to the arts as a universal language between nations. But for Ukrainian authors, musicians, filmmakers, publishers and painters, Russia’s war of aggression renders this notion unthinkable. In times like these, the arts have another role. They are the expression of the culture of a community past and present; of shared memory; of local, regional and national identity; of solidarity. They are a source from which Ukrainian society draws its sovereign will and the spirit of resistance with which it confronts the aggressor.

This is the translation of the editorial of Osteuropa 6–8/2022 (original here). It features in a Eurozine editorial.

It follows that we not only can but must discuss Ukrainian art and culture during war. Culture is a source of enlightenment about a country that for decades has been ignored, forgotten, repressed and treated as part of Russia. This misconception – particularly in Germany, but not only here – has been encouraged by Ukraine’s complex history. The Ukrainian regions once belonged to various multinational empires: the Romanovs, the Habsburgs, the Ottomans and the Rzeczpospolita. The Ukrainian national movement began fighting for independence in the mid-nineteenth century, at the same time as its German or Italian equivalents. But the Ukrainian nation-building process was unsuccessful and viciously repressed, particularly by the Russian Empire. Even members of Russia’s liberal intelligentsia denied Ukraine’s right to independent statehood.

On the ruins of the pre-war empires, the Ukrainians formed not one but two states. Ideological, political and regional differences aside, these state formations – the ‘Ukrainian People’s Republic’ and the ‘West Ukrainian People’s Republic’ – had one thing in common: they lacked the military strength to defend themselves. Both were destroyed: by the Red Army from the East and the Polish army from the West. This double defeat was grist to the mill of those who believed that Ukrainians lacked the strength to form a nation, and who perceived them at best as an object of history.

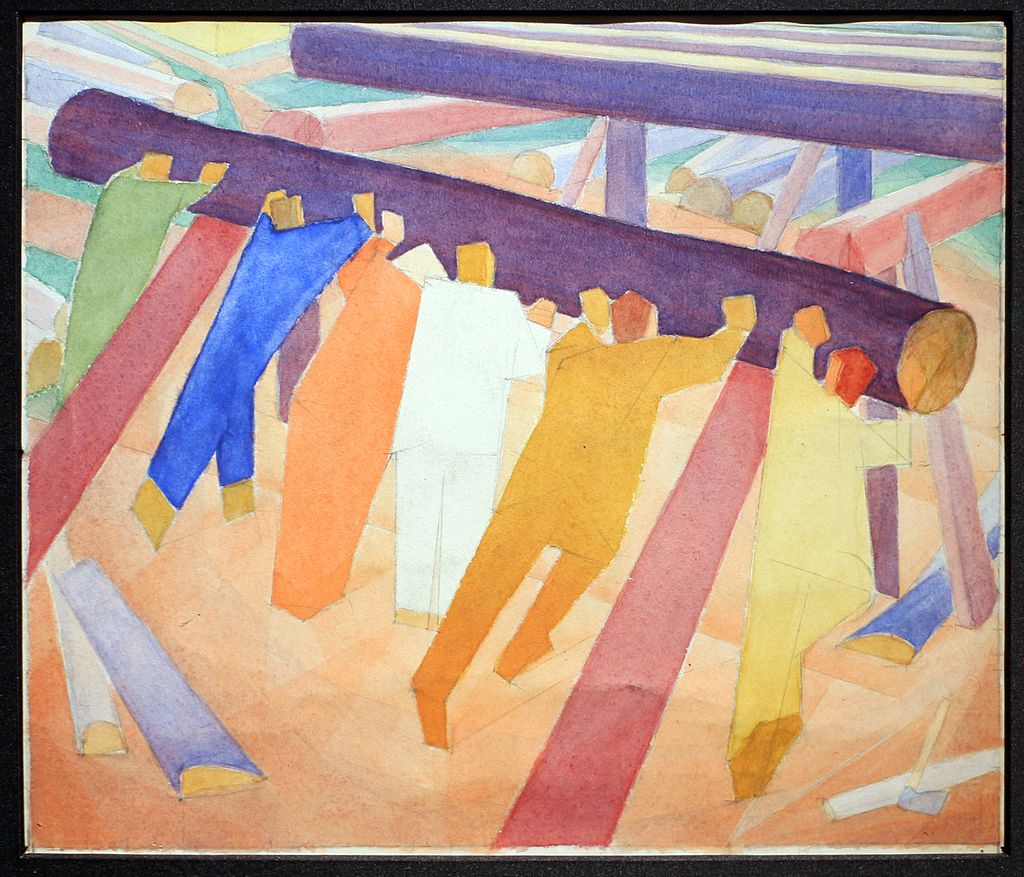

But the era of state-formation was also when Ukrainian cultural autonomy took off. The Bolsheviks supported the movement, seeing it as a way to consolidate the young Soviet Union. The 1920s was a period of breathtaking productivity in the crafts, painting, graphic art and book design. The Soviet avant-garde was to a large extent Ukrainian. There was similar progress in music and, above all, literature. Writers and artists saw themselves as representatives of Ukrainian national culture.

The flowering was short-lived. Under Stalin, cultural and linguistic autonomy was repressed and prohibited down to the smallest initiative. Hundreds of authors, poets and artists of the ‘Ukrainian Renaissance’ were shot dead and their works destroyed, banned and cloaked in silence for decades. The Ukrainian Communist Party shared part of the responsibility for the annihilation of Ukrainian national culture.

After independence in 1991, Ukrainians began to rediscover their cultural heritage. Dozens of new publishing houses reissued the authors, artists, composers and graphic designers of the 1920s. They launched series and published collected works. But the situation was difficult. The market for Ukrainian books was small and purchasing power weak. The wide currency of the Russian language in Ukraine, the dominance of Russian companies, illegal import and piracy were major problems for Ukrainian publishing and film.

Two political events changed that: the Orange Revolution in 2004 was the starting gun for resistance and autonomy; the Euromaidan and the annexation of Crimea in 2013/2014 were the watershed. Since then, a change in mentality has been underway. More and more people have come to understand the meaning of political and cultural self-determination. This has accelerated the shift away from Russia and boosted Ukrainian culture. The book market has profited. But war has made the situation more difficult than ever.

The goal of Vladimir Putin’s revisionist, neo-imperial regime is to destroy sovereign Ukraine, to bring down its regime and rob the population of its freedom and autonomy. But despite the shelling, concerts take place and books are printed in Zaporizhia and Kharkiv. This is not an expression of heroism or contempt for death. Every note, every book is a contribution to cultural autonomy.

Manfred Sapper and Volker Weichsel’s editorial for Osteuropa 6-8/2022 was written in Berlin at the end of September 2022.

Log Rolling, Alexander Bogomazov, 1928-29. Image courtesy of James Butterwick Gallery via Wikimedia Commons

Published 19 October 2022

Original in German

Translated by

Simon Garnett

First published by Osteuropa 6–8/2022

Contributed by Osteuropa © Manfred Sapper / Volker Weichsel / Osteuropa / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

On the occasion of Europe Day, Oleksandra Matviichuk, Ukrainian human rights defender and director of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Center for Civil Liberties, delivered this year’s Speech to Europe at Vienna’s Judenplatz.

Whether defending human rights on an international stage, checking facts from the frontline, processing traumatic experiences over a lifetime, or even questioning the language you have spoken since childhood – all matter in the collective fight for justice.