Addressing discrimination towards black people is a collective responsibility. Racism, evident in visual memory and disguised through political association, reaches beyond countries with direct colonialist pasts. Taking Estonia as a case study, historians and curators discuss how to ‘render race’ in museums and public discourse.

Across eastern Europe, the global Black Lives Matter movement has led to expressions of solidarity, as well as heated debates. In Estonia, this has been most visible in the controversy around renaming racially charged artworks at the Kumu Art Museum’s exhibition ‘Rendering Race’, a part of the museum’s new permanent exhibition, ‘Landscapes of Identity’ (2021).

Critics of the exhibition have included not just the usual suspects on the radical right, but people from all ideological and cultural corners of Estonian society. This debate over renaming artworks exemplifies how the histories and legacy of colonialism still need to be worked through in post-Soviet societies.

In the interview, historian Linda Kaljundi, one of the curators of the new permanent exhibition, discusses the broader context of the ‘Rendering Race’ exhibition with its curator, art historian Bart Pushaw, and historian of colonialism Aro Velmet.

Linda Kaljundi: Bart, you specialize in Baltic and Nordic art. How did you find your way to Estonian art history and its complicated relationship with race?

Bart Pushaw: During my Fulbright year in Estonia, in 2013, art historian Tiina Abel curated an exhibition at the Kumu Art Museum that included a display of ethnographic photos of Estonian peasants from the 1890s, made by an Estonian photographer Heinrich Tiidermann. Next to these were photos and paintings of Tunisians and Black Africans. This really intrigued me. These images come from a time when Estonia was part of the Russian Empire. Estonians also had a semi-colonial relationship with the Baltic German elites, who held most of the land and legal privileges in the region since the Middle Ages. The legal and economic situation of the peasantry improved significantly only in the late 19th century. Previously, Estonian peasants had been serfs who had often been compared to slaves in European colonies. In this context, what does it mean then, when in the late 19th century, Estonians began depicting Africans in art?

The other reason relates to my undergraduate studies at Indiana University. Estonian has been taught there since the 1950s when, during the Cold War, the university founded positions for migrant scholars to teach their languages and cultures. Today, Estonian shares a department with Central Asian cultures and languages, as well as Finnish and Hungarian. While studying Estonian with Piibi-Kai Kivik and history with Tovio Raun, I also came across Finno-Ugric topics, which highlighted issues of race and colonialism in Estonian history.

The third reason is that before coming to Estonia, I studied at the University of Chicago, an affluent private American university located in the middle of Black poverty. Since Chicago is one of the most racially segregated cities in the US, my part-time work at a Black elementary school made me confront the realities of racial segregation and the uncomfortable privilege of the fancy university that is protected and essentially walled off from the rest of the city. These factors influenced me as I started thinking about race and its complex entanglements in Estonia.

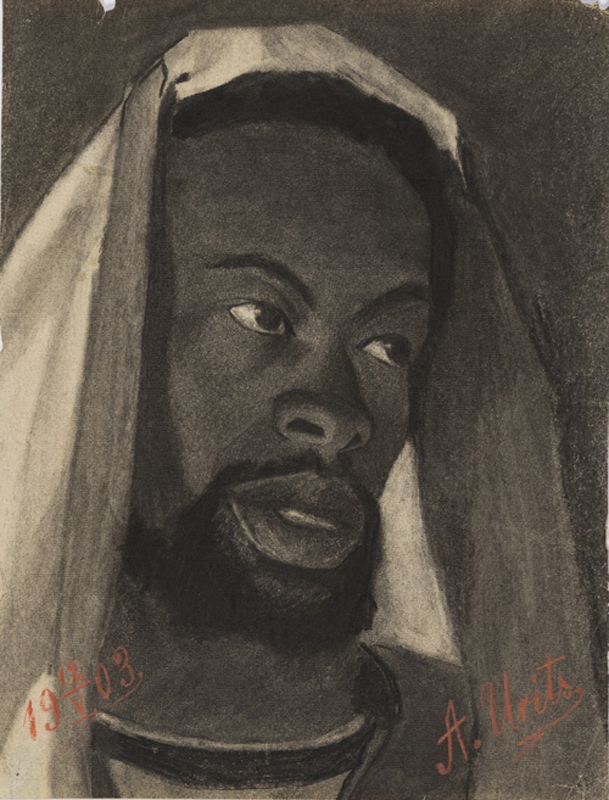

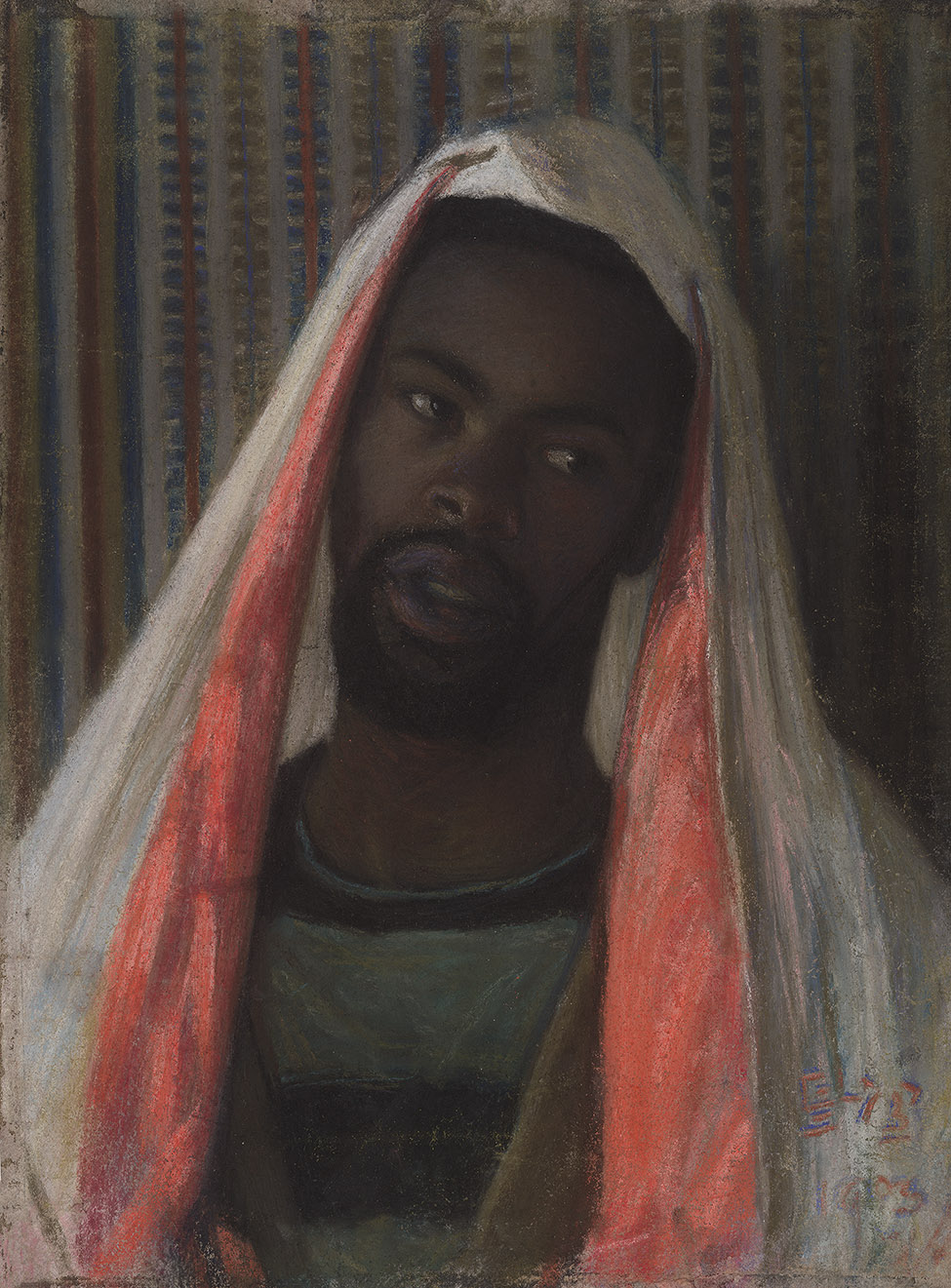

Aleksander Uurits, ‘Portrait of Samuel Peters’ (former title: ‘Abyssinian’) 1903. Image courtesy of the Art Museum of Estonia.

Linda Kaljundi: Well, this is a really multi-layered background. You also pointed to the complexities of Estonian and Baltic colonial legacy, which is very little discussed at present. How would you both explain the benefits of dealing with colonial history?

Aro Velmet: We are still living in a world that is defined by the legacy of colonialism in a number of different ways. First, there is an insistence in Estonian public discourse that we have nothing to do with colonialism, that our colonial legacy only has to do with once having been colonized by Germans and Russians, and later by the Soviet Union. When it comes to the nasty parts of colonialism, then seemingly we, Estonians don’t have anything to do with it. This argument is empirically false and I’ll just give one example.

A couple of years ago, I went to a talk about the photographer Juhan Kuus, a son of Estonian World War II refugees, who lived and worked in Apartheid-era South Africa. I was struck by the comments of someone in the Q&A, who first insisted that the Estonians have always been victims of colonization and then in the next sentence, he said that the Boers were exactly like Estonians! That was such a stunning comment, because you would intuitively think that if you’re talking about people who’ve been colonized, you would draw the parallel between Estonians and the indigenous peoples of South Africa. Instead the parallel was drawn with the white settlers. To me, this indicated how a lot of the Estonian nationalism is tied up as much with ideas of whiteness as it is about ideas of indigeneity – and that’s a really interesting paradox.

Second, and that’s one of the things that come through so clearly in Bart’s exhibition, Estonian history is deeply embedded in the history of colonialism not just on a discursive level, but also in very material ways. You display African statues that have ended up in the collection of the Estonian National Museum because they’ve been brought there by Estonian doctors who were a part of the French colonial mission and Belgian colonial medical services. These connections persist to this day, as Estonians accompany French soldiers in their missions to Mali, a former French colony, or participate in the US invasion of Iraq.

Estonia is a part of this postcolonial world in many different ways, and reflecting on this history is critical, because it helps unravel this narrative in which we have always been the ones colonized and bear no responsibility in the process of colonization.

Bart Pushaw: I was hoping to demonstrate with the exhibition how the Estonian attitude to race can change very quickly, as so much racial and ethnic diversity suddenly pops up in Estonian art in the 1920s and 1930s. We might not always be able to understand precise relationships between artists and subjects, but the fact that such images appear in such a high volume is really interesting.

This changing level of Estonian whiteness can be traced to a kind of a racial caste system that the Baltic Germans had created in order to maintain the distance between the elites and the non-German peasantry. But it also relates to rapid social change.

What changes in Estonians’ life from the 19th century into the 20th century is their social position, the kinds of things they can do, and the things that are made available to them. With new social mobility, they are also moving from the land to the city, from one city to another, to France, the UK, or the US. And from there, they are moving to Africa or to Latin America.

The speed at which everything was changing is dazzling, considering how the First World War, the Russian revolutions of 1917, and then the sudden emergence of the Estonian Republic, founded in 1918, all occur simultaneously.

Aro Velmet: Bart, you have also talked about the idea of ‘aboriginal whiteness’, which has become a kind of bedrock for thinking about Baltic or Estonian racial identity. I think this idea nicely illustrates the contradictions of racial identities, because we see how throughout Estonian culture, there is this attempt to simultaneously claim both markers of whiteness and markers of indigenous heritage.

The place you see it really well is the Estonian National Museum’s exhibit about Finno-Ugric peoples who linguistically belong to the same language group with the Estonians. A large part of that exhibition turns around Estonians being a kind of Europeanized torch bearers for all of these Finno-Ugric peoples who live in Russia and don’t have a nation state, and who, of course, are coded as non-white in most Western (and also Russian) texts. There is much less at the exhibit about the Finns and the Hungarians who occupy a very different place in the Western hierarchy of civilizations.

Unidentified Mangbetu artist, Clay figure, Collected ca. 1928-1934. Image courtesy of the Estonian National Museum.

Linda Kaljundi: So we could also say that this anxiety about BLM or, for example, your exhibition, Bart, is also caused by the existence of these two conflicting identity patterns: Estonians want to belong among the noble savages and at the same time, among the white Europeans. You already brought some examples of how museums construct such identities, but what about the critical role of museums in analysing colonial and national discourses?

Aro Velmet: Well, one way museums can provide a critique of colonialist discourses is by being aware and explicit about their own curating and collecting practices. Objects don’t end up in museums by accident, they are donated, they are sought out, collected, selected for a purpose. The way objects end up in collections can be really revealing: the Estonian National Museum has these African statuettes because Estonian doctors were part of French and Belgian colonial missions. Museums around the world are increasingly starting to acknowledge these stories, we’re seeing it even in institutions that used to be at the heart of colonial enterprises like the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University, which has started to structure its exhibitions around the colonial histories of their collection, rather than pretending to give some disembodied view of universal human history.

Linda Kaljundi: Coming to the Rendering Race exhibition, Bart, how much was your concept affected by the materials you discovered while preparing the exhibition? What surprised you the most?

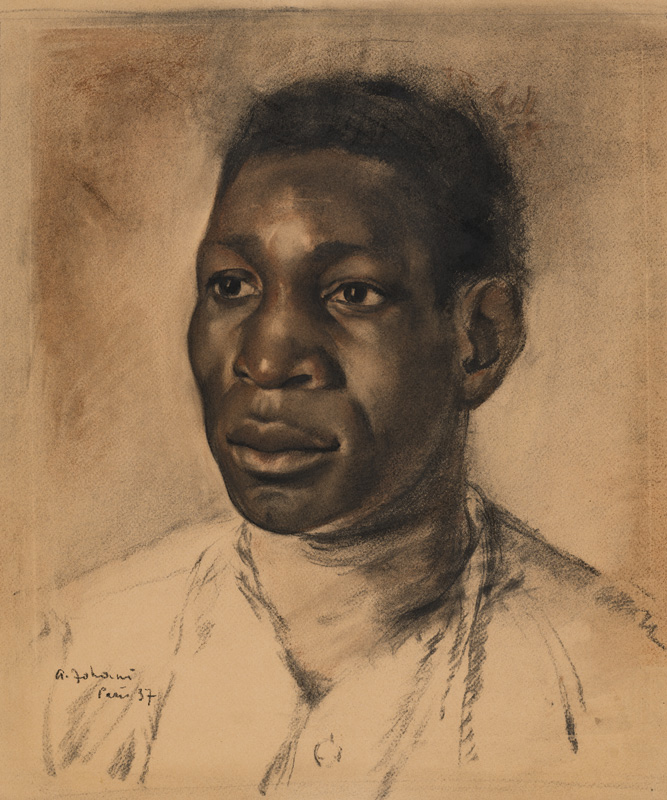

Bart Pushaw: I had been planning this exhibition for seven or eight years. So I already knew quite well how race and ethnic diversity rise into prominence in the Estonian art of the 1920s and 1930s. One surprise was an image that had not yet been digitized when I was planning the exhibition: a portrait of a Black man that Andrus Johani made in Paris in 1937. I found it astonishing, incredibly beautiful, and dignified. The moment I saw it I knew that I wanted it to be the promotional image of the exhibition.

Andrus Johani, ‘Portrait of a Man’ (former title: ‘Portrait of a Mulatto’) 1937. Image courtesy of the Art Museum of Estonia.

On the other end of the spectrum, I remember when the collection managers showed me the racist caricatures by Gori, the most prominent Estonian cartoonist of the interwar period. These really took my breath away in the worst way possible, although these kinds of anti-Black racist characters are typical in this period. At first, I thought I was not going to reproduce that violence by displaying them in the exhibition. But then I realized they warranted a nuanced display in order to acknowledge and confront what it means that these works exist in Estonian museum collections.

However, knowing that the intent of this imagery was to question Black humanity and to normalize Black denigration, I made sure to work closely with my exhibition designer Jaanus Samma. Originally, we thought of using curtains, but abandoned the idea due to Covid restrictions and in order to avoid the audience touching things. Instead, we placed the caricatures behind a separate wall that creates an isolated and intimate personal experience. On the wall, we placed a clear sign that explains what you are about to look at. In that way, no visitor is forced to look at them, but each visitor can decide on an individual basis.

This is not just an exhibition for Estonians to think about Estonian history, this is also an exhibition to demonstrate to Asian Estonians and Black Estonians and Middle Eastern Estonians and Latin American Estonians that they also have a history that goes deeper than whatever their own personal stories with Estonia might be. This had an influence on what images went up and what did not.

As someone who works with race in art history, I wanted to emphasize the importance of race as a phenomenon of visual difference, and critically question the assumed neutrality of ‘exoticism’. I believe having all these images in one place can have powerful implications for how people think about Estonian history: who lives and has lived in Estonia, where Estonians have gone, what have they done there and what changes when they return.

Linda Kaljundi: European museums have lately highlighted the role of visual culture in legitimising colonialism. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, colonial products became affordable to broader segments of European societies. The exotic designs for coffee, chocolate and other colonial wares were supposed to attract the consumer, but also to normalize exploitation and discrimination in the colonies. What do you think about the potential of everyday, banal visual culture in pointing to links between local and global colonial history?

Bart Pushaw: I display some tobacco packaging designs from the graphic design collections of the Art Museum of Estonia. Again, this is an instance of reconsidering the collections. It is important to my practice to not only talk about paintings and sculptures, but to have a broader idea of visual culture and its impacts. When a consumer sees, for instance, tobacco packages with demeaning caricatures of uncle Tom and similar racist imagery on everyday items at the grocery store, consumers do not question it because the imagery is ubiquitous. When people speak out about the violent impact of this imagery, however, the most apathetic are usually people who are not subjected to the humiliation of that imagery. Displaying these tobacco packaging designs is one way to reinvigorate connections between local everyday microhistories and the larger global circulation of peoples and things.

Aro Velmet: I think Bart is pointing to something very important here. Contrary to the way that this is often discussed in Estonia, colonialism is not just an exercise of state power. It is also a part of a political economy of production and consumption. So one of the things that those tobacco boxes, for instance, force us to confront is, where does that tobacco come from anyway. It is not by accident that it was (and still is) produced in a large proportion in places like the Caribbean or the southern United States, which have a long history of colonialism and slavery. These societies depend on consumer markets for their existence. So by participating in the consumption of tobacco you were not only normalizing that visual imagery, but you also participated in the colonial economy. In that way, Estonians, neither in the 20th, nor in the 21st century, are in any way exempt from the circulation of capital and power and military might.

There are important differences, but there are also important similarities between the colonial economies of the early 20th century and, say, the production of textiles in the 21st century in places like Bangladesh. To think that we are somehow relieved of responsibility, just because we are not the people whose boots are on the ground, is a kind of convenient fiction.

Linda Kaljundi: In discussing how to display racist caricatures, Bart has already touched upon museum ethics, closely related to replacing offensive titles, which has created much debate across the globe. In your opinion, why does the renaming of artifacts provoke so much criticism? And how would you try to convince the critics that it’s necessary practice?

Bart Pushaw: In Estonia, a lot has already been said about the fact that the old titles are very often given by museum collection managers and not by the artists themselves. What has surprised me the most is not the reaction, but the diverse array of people from different kinds of political affiliations, that were annoyed by the exhibit.

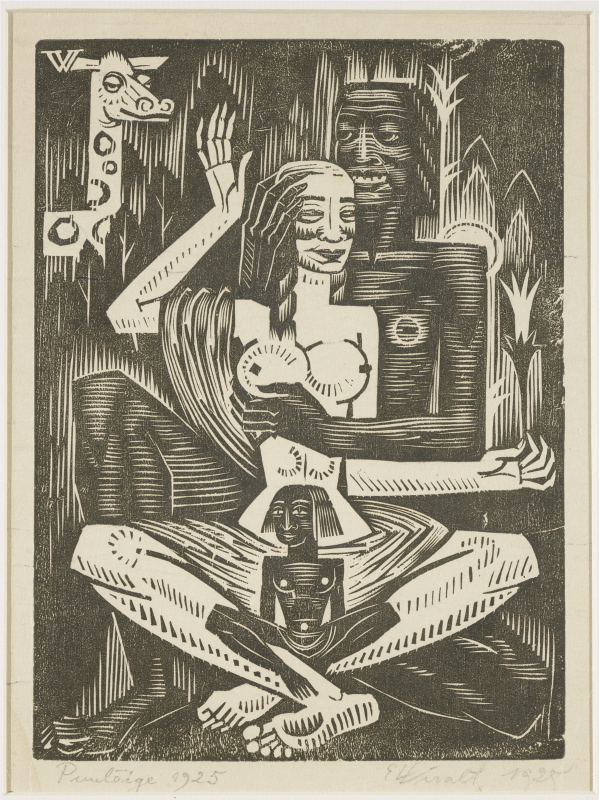

I was definitely expecting some adverse reactions, but I was shocked by who was saying them, including colleagues who had followed and supported my research thus far. I think one of the reasons is that people are connecting renaming with a negative evaluation of the artwork and the artist. They seem to think that if a title is offensive then the artwork is offensive – for example, some work by the popular and beloved Estonian modernist Eduard Wiiralt. Some commentators even suggested that burning artworks was the next step after changing titles. Such reactions are deflection mechanisms. To a similar extent, critiques about my American background are also deflection mechanisms to avoid the problems the exhibition raises. The exhibition does not make final judgments, but raises questions. That is why the exhibition features both old and new titles.

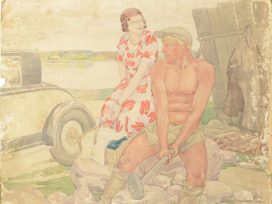

Eduard Wiiralt, ‘Family’ (former title: ‘Oriental Motif’) 1925. Woodcut. Image courtesy of the Art Museum of Estonia.

The other major factor stems from the fact that my exhibition opened after the resurgence of Black Lives Matter at a global scale after last May and June. People are drawing lines, but of course, the preparation for this exhibition began much earlier and thus it is just fortuitously coincidental with the renewed global focus on BLM. The decision to change the titles came early at the planning stage, and for my colleagues at the museum, it was such an obvious thing to do. Renaming the works was not even a debate, but instead the conversation focused on how to do so most effectively.

Aro Velmet: The thing that the critics of the renaming practice get right is that names do matter. It is significant what you name something, and we know that. The second thing I find really telling is how some critics are comparing Bart’s exhibition to Soviet censorship, or other kinds of totalitarian practice. You rename a work of art, you desecrate the intention of the artist, and as you said, Bart, the question then becomes, what is next, do we burn the works of Eduard Wiiralt? This is a clear reference to Nazi and Communist regimes and totalitarian thought policing, as if the museum was putting on some show of entartete kunst, or sending in glavlit to scrub out titles they don’t like.

First of all, this is just patently not what is going on at that exhibition. The exhibit is not about closing things down and making things less accessible, it is about opening up the collection of the museum and putting these works – many of which have not been exhibited before and certainly not as a part of the permanent exhibit – in their historical context. The names that the previous curators have used have been retained, as you are just adding new titles.

Second, Estonians themselves have changed a lot of names both in the 1920 and 1930s, and after 1991. After regaining independence from the Soviet Union, we took down a lot of statutes. Communist monuments populated literally every city in Estonia and now those no longer exist. Many streets were also renamed and the old names were not kept. Whenever a foreigner asks about this, we plead for understanding. Saying, for example, that we understand that in Greece or in Italy the resistance during the Second World War was intimately tied up with Communism, but please understand that we come from a place where Communism is associated with mass death, deportation and the loss of sovereignty.

If certain Estonian nationalists can ask Greeks or Italians for this courtesy, then why would the groups who are hurt by the offensive portrayals of racial stereotypes have any less of a right to ask for sensitivity in displaying this global visual discourse of racial difference, which is so seeped in a history of violence and dehumanization? We cannot say that Estonians did not participate in this history, as indeed, the exhibit itself catalogues in a very careful and systematic manner all the ways in which we did!

Bart Pushaw: At its very core, renaming is just about respect. We were just choosing ways to respect Black and Brown people. In Estonia, people do not often realize that the N-word has a very violent, very frightening history. I knew that avoiding this word would set people off, but this is also just the initial reaction. This is the first time an Estonian museum affords such changes, creating a clear precedent for the rest of the country. It’s actually very progressive, as many other European countries haven’t even started this process.

Ants Laikmaa, ‘Portrait of Samuel Peters’ (former title ‘Abyssinian’) 1903. Image courtesy of the Tartu Art Museum.

Aro Velmet: One of the places where the idea of respect is most evident also is maybe my favourite bit of your exhibition, Bart. This is the portrait which was originally titled ‘Abyssinian’. Together with the art historian Liis Pählapuu, you found out that this is actually a specific person, Samuel Peters. By putting his name on the title you are losing nothing of the original context. You can observe the same complex story of orientalism, colonial politics, and also the personal relationships involved. But what you have gained is an actual appreciation that this person is more than just a representation of a white artist’s idea of Blackness. So it is just baffling to me that somebody would think that this is anything other than a win-win proposition.

Published 3 May 2021

Original in English

First published by Eesti Ekspress (in Estonian) 30 March 2021, Eurozine (English version)

© Linda Kaljundi / Bart Pushaw / Aro Velmet / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

War – what is it good for?

Vikerkaar 7–8/2021

‘Vikerkaar’ on the overlooked aspects of war – from the long-term impact on veterans to conflicts that rarely receive widespread coverage but cause no fewer casualties.

Let’s make cabbage great again

Podcast: Vaccines in West Africa and whiteness in the East of Europe

How is whiteness constructed and why is it so fragile? What’s at stake in discussing colonial memory for eastern Europeans? Do they actually eat a lot of cabbage?