The memory of my first encounter with racism is sadly too vivid, even though it happened almost twenty years ago. A funfair had arrived in Brno, with its kitschy merry-go-rounds, which I went to ride on with my father and a friend. We sat down in a mock flying saucer, and just before it took off we saw a boy zigzagging between the various amusement attractions. A Roma, not much older than I. Pursued by a gang of Neonazis, baseball bats in hands, chasing their prey. The anxiety and hopelessness I felt watching the hunt for this poor kid is something I can neither forget nor blot out. But actually I am glad that I remember.

In those days, ‘Gypsy hunts’ were quite frequent. The term ‘racist murder’ was only just beginning to take roots and find its place in the legal and social vocabulary. In those days, some sections of the population were dismayed by the sight of Roma men and women becoming targets of brutal and premeditated murder which had a single motive: the colour of their skin.

In those days, the Roma were not protected by the state and the thugs walked away from courts with laughably minor punishment. Even though in most cases, they killed or hunted just for fun. The names of the murdered Roma remain unknown to most people. There are quite a number of them, and they are not just a spectre from a distant past.

Recalling individuals

Emil Bendík, beaten to death with rods. Tibor Danihel, drowned by the Neonazis for fun. Milan Lacko, kicked unconscious and left in the road to be run over by a car. Helena Biháriová, thrown into the flood of the Elbe River. Karel Balogh, stabbed repeatedly with a knife at a nightclub. Radek Rudolf, a six-year old boy, brutally beaten by a drunk Neonazi, and stabbed several times with a glass shard. Oto Absolon, killed by multiple knife stabs. And also some foreigners: Sudanese Hassan Elamin Abdelradi, stabbed to death by the Nazis. Or an unknown Turkish citizen, mistaken by the Neo-Nazis for a Roma and beaten to death with chains and rods. Miroslav Demeter who died in unexplained circumstances after excessive police handling.

To all those names we may add numerous anonymous violent attacks, sterilisation of Roma women against their will, arson attacks, or the hate marches bordering on pogroms, sometimes prevented by groups of activists. And daily occurrences of structural oppression and humiliation, life on society’s fringe, often spent in fear.

‘I am saving a few hundred crowns from each wage payment to have some for when we have to leave,’ one Roma friend told me after a discussion with high school pupils. It brought tears to my eyes. I was shocked by what she had to listen to from her peers. And yet, she replied calmly to the most racist fallacies and hoaxes, explaining to her audience that she really did not receive a hundred thousand crowns in social assistance, or that Roma are not beasts raping blond girls.

Had I been in her place, I would have told them all to get lost, and left. Just to watch the humiliation of her defending her very existence was maddening. And she had to live with this every day? This has been aptly described by such journalists as, for instance, Fatima Rahimi.

Memorial not enough

Lety, Prague-West District, Central Bohemian Region, the Czech Republic. Řevnická street.

Photo by Mirekk, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A few years ago, the government approved the purchase of the pig farm in Lety and its reconstruction into a memorial of the Roma holocaust. Here, where Roma men and women died with the complicity of Czech police, the embodiment of our greatest shame as Czech society has stood for decades. We called it ‘The Memorial of Czech anti-Gypsyism’. It aptly expressed Czech society’s attitude toward the Roma. And not just that – it stood there as evidence of how much we have been trying to exculpate ourselves from our complicity in the Roma holocaust. Of how much we refuse to confront it, how much we want to deny it.

The story of our shame at Lety is gradually coming to its conclusion. The Museum of Roma Culture presented its first visualization of the new Memorial of the Roma and Sinti Holocaust in Bohemia. The public competition for its design was won by Atelier Terra Florida and Atelier Světlík. Their winning design symbolizes a forest. The demolition of the pig farm is to begin soon and by 2023 the site of the tragic suffering of Roma and Sinti may at last become the first sign on the way to a dignified recognition of Czech-Roma historic debt.

In recent years, streets and squares have undergone a new wave of renaming. In their own way, the changes always serve as a political statement, locally and globally. The need for the politically inspired renaming of streets is in itself debatable. The square in front of the Russian embassy was renamed after dissident Boris Nemtzov, even though its previous name was harmless – ‘Under the Chestnut Trees’. The idea was to show Putin who is boss here. We, the Prague citizens, of course. A petition was in circulation for the renaming of Marshall Konev Street in Žižkov to Maria-Theresa Street, since, if his statue is being moved into storage, no trace of this Bolshevik must be left anywhere.

Some of the debates about public space are quite debilitating, partly because rarely do they express the need to come to terms with national history and responsibility. To name streets and squares after Roma victims of hate violence could be an ideal way of fulfilling such a purpose. It could start a journey of self-reflection and of starting to repay the debt, which the greater part of society owes to the Roma. But without additional structural changes, even this would remain just an empty gesture.

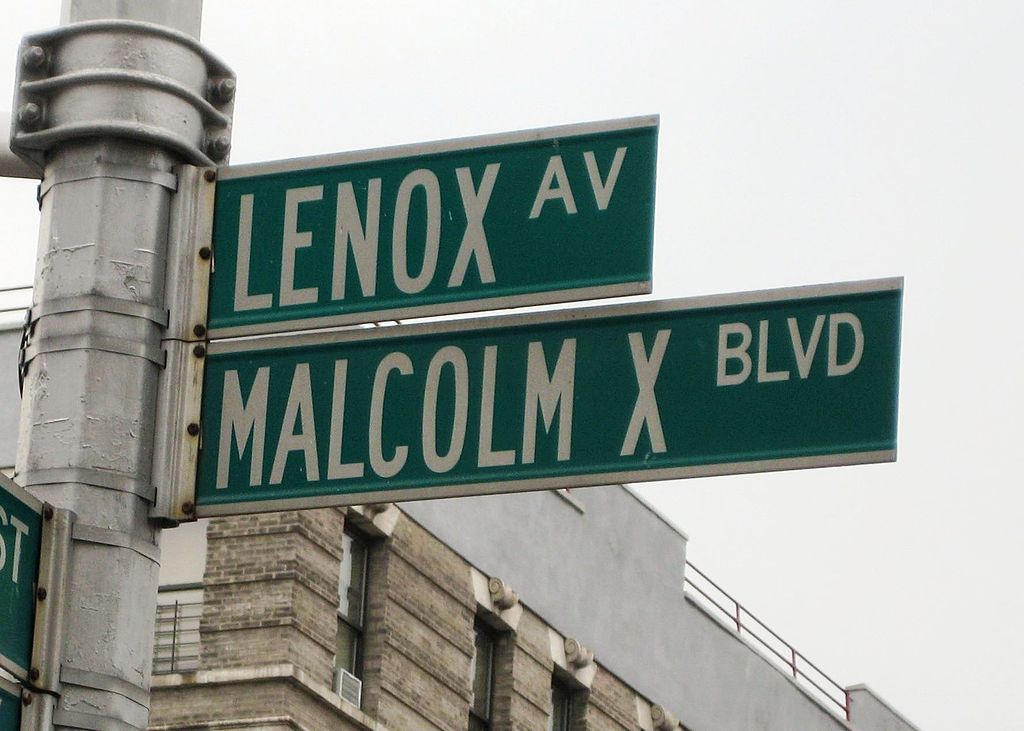

Last year, crossing the imaginary frontier between the northern corner of New York’s Central Park and Harlem, I fell into a spiral of ambivalent emotions. We were standing at the top of Malcolm X Boulevard, named after one of the most important personalities of Afro-Americans’ rights movement. Like other places – Marcus Garvey Park or Adam Clayton Powell Junior Boulevard – the Malcolm X Boulevard, cutting through the heart of Harlem, is a painful reminder of Afro-Americans’ (and other ethnic groups’) endless struggle for equal rights in the United States.

Prednadrazi a Roma Neighborhood in Ostrava, Czech Republic

Photo by Daniel Arauz from Flickr

Evidence of continued racism that for us, who are not living it, is hardly imaginable and will not go away until we self-critically accept it as a bare fact and support all ostracised people in their own struggle for a just world. Were I standing on Malcolm X Boulevard today, I would feel even more out of place there after the police murder of George Floyd. A street bearing the name of a black radical is a bitter reminder that symbolic recognition is not enough.

Symbolic recognition not enough

Discussions on current events in America often suggest how important it is to consider the Czech context, too. It differs fundamentally – starting with the fact that police in Europe are on the whole not so violent, and because we in Czechia do not believe that our racism pushes the Roma to the fringes. We do not value their memory because we do not value them, so we wouldn’t think of sharing the public space with them. It would of course be absurd to think that Roma-named streets remove racism from Czech towns. It would be improper to use names of the murdered to embellish today’s Roma ghettoes, as it would be just as ridiculous to plant them in the new luxury developments where housing is beyond the reach of most of us, let alone the socially deprived.

However much I may be yearning for a Helena Biháriová Street or a Tibor Danihel Square, I do not want them to serve as a cover-up of a further deepening of unequal treatment of our Roma. Any Roma-named streets would make sense only if all levels of society – from education and housing to social recognition – make an effort to ensure that Roma families can live not only without fear of violence but in the hope of a better and more just life.

This article was nominated for the 2021 European Press Prize Opinion Award.