Proposals for intervention to de-escalate war are on the rise. Various commentators, especially from Germany, have thrown their pacifist hats into the ring: elder generation feminist Alice Schwarzer and Die Linke outlier Sahra Wagenknecht have launched a ‘Manifesto for Peace’ calling for talks and a halt to arms deliveries; Jürgen Habermas’s ‘Plea for Negotiations’ proposes a global a return to a pre-2022 division of territory and a multilateral disarmament agreement. But their suggestions are causing a wave of controversy. Who indeed would consider sitting down calmly at the table with their aggressors while atrocities are still occurring in the next room?

Bearing witness

Some discussions are happening when all are focused on managing the fallout born of conflict, however. Documenting Ukraine, an Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) project, recording the Russo-Ukrainian War, held a round-table event this month where representatives from various monitoring and cultural organizations spoke of bearing witness to war.

Large parts of Ukraine are lying in ruins. An image of the ‘land of emptiness’ helps the Kremlin’s imperialistic drive, as if obliteration signals there was never anything much to be protected in the first instance. Despite such harsh devastation and misrepresentation, when discussing what of Ukraine’s cultural heritage should be preserved and how, participants recognized that the war has thrown a spotlight on what had previously been ‘collecting dust’.

Rural, industrial eastern Ukraine, contested land, decimated and scarred, once relegated to the cultural periphery, is being reclaimed and valued as a proud site of national heritage. Initiatives such as the Old Khata Project document unique artifacts that may have otherwise been forgotten: decorative houses in villages, where daily life is being repeatedly bombarded, are being photographed for a visual archive – elevated from poor, naïve dwellings to important markers of tradition before they disappear.

Iconoclasm and memorial

When considering historical cultural emblems, monuments in Ukraine, especially those from the Soviet era, have become an unavoidable topic for debate. Violent knee-jerk reactions abound: Ukrainians repair Russian-wrecked post-communist memorials; Russians are following suit, touching up Soviet memorials trashed by Ukrainians. In sociologist Mischa Gabowitsch’s opinion, even how Soviet-era artifacts are termed is a sensitive issue, influencing the politically-fuelled rationale for destroying or preserving controversial objects.

Physical reminders of a contested past are also layered in everyday significance. What happens when a small-town monument to the ‘Great Patriotic War’, a local meeting place, is removed? Should all the personal memories associated with its presence be threatened with erasure alongside its politicized meaning? Everyone around the table agreed that Soviet artifacts are a legitimate part of Ukrainian culture. Rushing to decolonize Ukraine’s cultural landscape was seen as potentially damaging to the country’s complex heritage, also undermining the role museums can have in contextualizing the past.

Art masters and selective vision

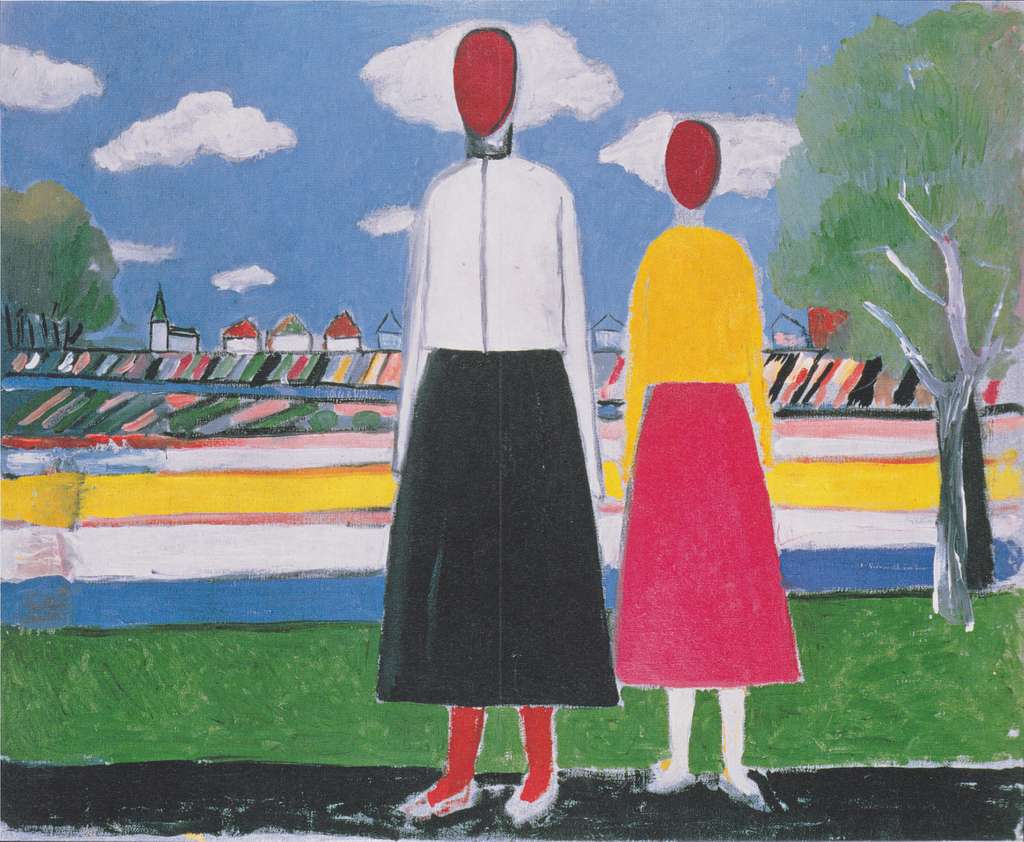

Ukraine’s regional museums are another reflection of its Soviet past. Historically, much art from Ukraine followed strong local traditions. Modernist artists were subsumed by the USSR when in political favour, migrating to the metropoles to achieve greater prominence.

International collections, following the established legacy, still label their artwork as Russian: Vienna’s Albertina museum, for example, classifies Kazimir Malevich’s work as Russian avant-gardism. But the painter was born in Kyiv to Polish parents. Some cultural centres are already making amends though: In the Eye of the Storm, a current mega show of Ukrainian modernists in the Thyssen, Madrid, is a leading example.

As a reminder of the complexities surrounding cultural reframing practices, curator Serge Klymko pointed out the inherent complications in selectively defining cultural significance: refuting Malevich’s Soviet context, for example, could risk simplifying the artist’s history. Decontextualization was seen as a poor solution to establishing the relevance of Ukrainian creatives.

Getting the picture straight

Equally, it was agreed that Ukrainians have to take charge of their own representation so that the biased impressions of others – from Russia and the West – don’t dominate. The question, however, isn’t ‘what is Ukrainian identity’. As Documenting Ukraine project manager Kseniya Kharchenko asserted, ‘Ukrainians know this.’ But how this cultural identity is perceived from the outside needs clarification. Kharchenko proposed a cultural pack for Ukrainians abroad, available as a handy reference to set the misconceptions of curious others straight.

Literary scholar Sasha Dovzhyk knows the necessity of having to repeatedly explain the basics. In London since Maidan, she has acclimatized herself to being asked where Ukraine is and appreciates the need to explain now what Ukrainian culture is ‘to relieve future generations of the task.’

Kharchenko believes in initiatives that encourage Ukrainians to talk. Much of the war is being documented externally, from a privileged position. ‘Intangible heritage is important’, she says, to identify whose truth is being preserved and safeguard that it isn’t being idealized.

Evidence testing ground

Sebastian Majstorovic, a data historian already practised in retracing multi-ethnic Bosnian identity, advised that logging and communicating what may seem like obvious detail needs to be consistent; western media need to see proof before reporting a story, he said.

Journalist Nataliya Gumenyuk underlined the importance of admissible evidence. Working with prosecutors on-site when documenting war crimes has given her insights into how to follow strict procedures. The likelihood of evidence being accepted in court is therefore increased. But Gumenyuk is still cautious of raising witness expectations. Those who submit evidence understandably want to see the result of their testimony, which is not always possible. And there are those who limit what they say for fear of being accused of lying – fake news’ legacy. As a result, Gumenyuk is in favour of recording the testimonies of war crime victims as quickly as possible. Although this practice may raise concerns of exacerbating trauma, she finds the approach better than risking memories mutating.

When reflecting on the potential success rate of new technological and procedural forms of documenting war crimes, her opinion takes a philosophical turn: Ukraine will likely be the testing ground for better practices applied to future conflict, she said.

Extreme experiences can put things into perspective – the survivor’s mindset is often pragmatic.

A non-monolithic culture

At several points of the discussion, heritage’s susceptibility to discrimination was raised: not only what’s considered in and out but also who’s deemed in and out were seen as key issues.

As moderator Sofia Dyak concluded, cultural heritage ‘has to have space for many hats.’ Ukraine’s different ethnicities provide a mix of perspectives to consider: Jewish, Crimean Tatar, Polish, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Roma and, last but not least, Russian. The issue with proposing a ‘simple’ reallocation of parts of Ukraine to Russia disregards the fact that contested regions are ‘ethnoculturally diverse’ – the term used by Volodymyr Kulyk, writing for Eurozine, to more accurately describe those who are often outwardly labelled as having either Ukrainian or Russian sympathies. ‘While some ethnic minorities remain distinct,’ writes Kulyk, ‘the boundary between people formerly categorized as Ukrainians and Russians has all but disappeared. … Disagreements about the content of Ukrainian identity persist, but these are no longer seen in terms of confrontation or competition between different ethnic groups.’ Annexing any part of Ukraine is a painful prospect, and one that doesn’t necessarily promise an end to war, nor peace for the foreseeable future.

‘Documenting Ukraine: Bearing Witness to War’ was held at the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) on 7 & 8 February 2023. The event was hosted by Katherine Younger. Launched in March 2022, the programme supports scholars, journalists, public intellectuals, artists and archivists based in Ukraine as they work on documentation projects that establish and preserve a factual record – whether through reporting, gathering published source material or collecting oral testimony – or that bring meaning to events through intellectual reflection and artistic interpretation.