‘On a deep, cultural level, people actually believe that if you don’t do something that at least mildly frustrates you, then your work is not valuable.’ Anthropologist, activist and bestselling anarchist David Graeber on the police state, bullshit jobs and why people need no telling that capitalism is bad.

Aro Velmet: When you visited Estonia in 2003 and spoke about the Movement for Global Justice, it was a pretty bleak time for progressives. Only a couple of years had passed since 9/11, the Iraq War was gearing up, and the protests seemed to be failing. But one of the interesting things you noted then and which you remark upon again in your essay, ‘The Practical Utopian’s Guide to the Coming Collapse’, is how in retrospect the movement turned out to be a lot more successful, even if it felt like a lost cause at the time.

David Graeber: Right. We were defeated in the field. We all knew after the 9/11 attacks that there was going to be a crackdown on all kinds of dissent. What surprised us was how long it took before the structures really were in place to simply nip street movements in the bud. This is called the Miami model. During the Miami global trade talks, they used overpowering force to crush protestors immediately. A lot of people were badly hurt, there were mass arrests, use of torture, everything.

But if you look at what was actually happening inside the summit at the same time, they were basically conceding defeat on any kind of project to create a kind of neoliberal zone in the Americas that they’d been pushing for years. So the major thing we were trying to stop was, indeed, stopped. We had planned a massive action against the IMF, we were going to step up the action in various ways, but then the Twin Towers went down and we were like, ‘shit, should we even do this?’ We finally decided we should, just as a morale boost for other people in the movement. If you are one of three anarchists in, say, Des Moines, Iowa, then you’re going to be feeling awfully lonely right now.

So we did it, and we were not surprised at how many cops there were. They outnumbered us two to one, or, as they say, four to one, by weight. These were huge cops, heavily armoured, surrounding us and kettling us right next to the World Bank building. Normally they don’t let us go anywhere near that building because it’s entirely made of glass. So it was obvious what was going on, they were like ‘come on assholes, smash one, I dare you.’ They just wanted to find a chance to beat us up, and of course we weren’t going to give them that. At one point, one of us ordered a pizza to see if they could get it through the lines. But we went home pretty depressed and demoralized.

Then I talked to someone who was married to a World Bank person, and they said it was just the most horrible experience of their life, there were eighteen layers of security, they got frisked. These are meetings where the richest and most powerful people in the world get together to celebrate their richness and powerfulness, and they basically turned it into this nightmare. Half of the people didn’t even go, they telecommuted, parties were cancelled. So they shut down the meetings for us. This made me realize: They must think we are really important. What do they know that we don’t?

In other words, it was becoming clear that unless they sent these continuous demoralizing messages, the movement would become infectious and spread. And this is what happened very briefly during Occupy! Most people don’t understand that – they think there was this strange little effervescence and then it sort of evaporated, what happened?

Well it’s very simple what happened. Everybody in America was convinced they literally lived in a police state, that if you go out to the streets and demand change, even if you non-violently sit in a park, RoboCops will come and beat you up. And for a moment, when we did this thing in Zucotti Park, that didn’t happen! Everybody was like: ‘What? You mean this actually is a free country? We can actually protest?’ And so they came. And then, in about two months, the cops said ‘no this is not a free society’ and they beat them up again.

It’s not that Occupy dissolved, but you can only create a movement for direct democracy if you can get everybody out in some kind of public place. They have to be safe enough to go there. So if going to an Occupy march means risking getting beaten up with stick, or being thrown into prison, then people with children, old people, they’re just not going come. And then only the hardcore activists come. It’s that simple.

Image: Tony Webster, Wikimedia

So from this perspective, 2017 seem pretty bleak again. Particularly since the some of the most important tenets of the movement – the opposition to corporate globalization and neoliberalism – has been appropriated by the Right and by people like Donald Trump, whose idea of justice is, if anything, more authoritarian and more top-down.

Trump is very much mixed-message on that. In a way, there were always men like him and they never got much attention, because people would have much preferred our kind of alternative. I was actually thinking of writing an open letter to the liberal establishment. Basically to say to people: look we tried to warn you! Most people in America think that the political system is fundamentally and totally corrupt, and they have good reasons for thinking that. It’s only the people in the professional-managerial classes, which are the core constituency of the Democratic Party, that actually believe that if you make bribery legal, then it’s okay. Nobody else thinks like that.

So we tried to channel that in a positive direction, and then they came and beat us up. It was the liberals that did it. It wasn’t the Right. The mayors who suppressed Occupy! were largely democrats, it happened under a democratic national regime. So now those guys are reaping what they’ve sown. The Left, or what claims to be the mainstream Left in America, basically sees as its main enemy the radical Left. That’s not true on the Right. That’s why they win.

The right wing knows that if you sell out your extremists on existential issues, then you can’t sell them out on policy issues, because they are not there. So if the Democrats were so ironclad about the First Amendment as the Republicans are about the Second Amendment, then we’d still be there, and Trump would never have happened.

I don’t know what’s going to happen with Trump and Brexit, but the irony is that these guys actually are what we were falsely accused of being. They said that we were anti-globalization. We weren’t. We called ourselves the Globalization Movement or the Global Justice Movement, we wanted an alternative to corporate globalization, we were about effacing borders. But if you supress that movement, then what you get is a real anti-globalization movement.

An overlooked part of the populist movement has happened in places in the Global South, and in the former Eastern Bloc, and largely predated Trump and Brexit. This wave of rightwing nationalism includes Narendra Modi in India, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, but also the events in Poland and Hungary over the past couple of years. These were supposed to be places of hope and the most fertile ground for anarchist movements. So what happened to that?

These hopes are still there. The real question is: what actually gets institutional support? If you look at someone like Chavez – he was basically an authoritarian internally, but did a lot of good stuff externally, such as getting rid of Latin American debt – so that guy, even though he was really not that radical, faced continual attempts at coups, rebellions, plots. Someone like Duterte – is the CIA trying to take him out? I don’t think so.

When you get outright fascists, somehow that’s okay. If you have leftwing populists, then the rules are entirely different. The entire system springs into motion to undermine you and kick you out. This is telling. The movements are there, but people, over time, learn the lesson that to vote for left populists is an act of defiance, because you know you’re going to be bringing all sorts of pressure on yourself. You’re voting to turn your country into a battleground, essentially. So it’s no wonder many people just shrug their shoulders and say ‘oh, fine, this guy is gonna do half of that – but he’s actually gonna be allowed to get away with it.’

In addition to international pressure, you also argue that people are kept in the neoliberal system by ideology, particularly when it comes to the morality of debt and the morality of work. There’s been quite a bit of discussion about the morality of debt, so let’s take the morality of work. Why is this an important issue in the struggle for direct democracy?

That’s what I’m working on right now. In 2013 I wrote an essay titled ‘On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs’, which turned out to be the most successful thing I’ve written. It was based on a very common experience. I don’t really go to cocktail parties, but when I do, I tend to run into at least one person who doesn’t like to talk about their job. So I explain, that I’m an anthropologist, and I do fieldwork in Madagascar, and they’re all very interested, but when we start talking about their work, they quickly change the subject. And finally, after they’ve had a few drinks, they say ‘don’t tell my boss, but I kinda don’t do anything.’ They’re these mid-level managers who present charts at meetings, but actually nobody wants to attend these meetings, and nothing really changes as a result. So I call these kinds of jobs ‘bullshit jobs’.

It’s very interesting that nobody considers this to be a social problem. Partly because the free market ideology says this cannot exist. These kinds of bullshit jobs were able exist in the Soviet Union, where you hired five people to sell a piece of pork, but not in the capitalist West, and particularly not in large profit-oriented companies. Efficiency is one of the biggest advantages of capitalism. So how could this even happen?

I also wanted to know how many people are out there who feel that their jobs are bullshit jobs. I was astonished that two weeks after the essay was published, it had been translated into thirteen languages, the website was constantly down, because it was getting millions of hits per day. This made me realize, oh my God, this thing is more common than I thought! Finally, YouGov, one of the big UK polling firms, ran a survey, which directly used my language, and it showed that 37 per cent of the labour force does not think they contribute meaningfully to society. Fifty per cent thinks that their work is useful, and 13 per cent are not sure. That’s pretty impressive, considering how many jobs there are that are impossible to consider useless. If you’re a nurse or a bus driver, you obviously contribute to society. Your day might be filled with useless crap, but you known that at the end of the day, you do useful work. To me, this survey basically showed that everybody who you suspect might think their job is useless, actually thinks it is useless.

How is this possible in a market economy? Partly because we don’t actually live in a market economy. Most firms are very big, they’re actually oligopolies, they have relationships with governments, and they actually like regulations because it drives out competition, as small companies cannot afford to hire all the bureaucrats. But it’s not just that. It seems to me that we’re dealing here with a fundamental question of how we understand the morality of work. On a deep, cultural level, people actually believe that if you don’t do something that at least mildly frustrates you, then your work is not valuable, that you’re not contributing.

This makes me think about how bullshit jobs are related to your analysis of bureaucracy. First, because bureaucracy is a primary creator of bullshit jobs. It’s a really easy way for generating all kinds of paper pushers, administrators, form-fillers, and so on. Second, this highlights – and you describe this really well in your recent book – how these kinds of jobs deepen the role of state violence in our lives. After all, the reason we are required to deal with bureaucrats is because, if we don’t, then we’ll be politely asked to leave, and if we don’t, then the ‘decision-makers’ call the security and they throw you out.

Exactly. Have you seen the film I, Daniel Blake?

That’s precisely what I had in mind.

Right – there are these huge security guys who grab you and throw you out if you happen to behave like a human being.

Could you discuss the implications of this idea?

Yeah, well, I’m old enough to notice how the securitization of everyday life is just shocking. When I was a kid, my parents and I used to visit a little resort town on Fire Island, near New York. Nobody really lives there during the winter, but over the summer, it has a lot of families with children visiting the beach and generally having fun. When I was growing up, maybe once a month somebody would spot a cop, and we’d go around running ‘a cop, a cop!’ It was that rare. It was an island of mostly well-off people and it was assumed that there would be security.

Now, we’re in this moment where, on your way there, there are three-four huge private security people on the ferry, with their special t-shirts, with their walkie-talkies, walking around and making sure that nobody gets too drunk. As soon as you hit the beach you see a small police station, and the cops on patrol, so you end up thinking: what the hell happened here? The places where it used to be weird to see guns around have basically disappeared. There are cops on playgrounds, in hospitals, schools, all institutions have become basically battlegrounds, or at least it is presumed that they could do so at any moment.

I can’t help but get the impression that this development has something to do with the financialization of the economy. Finance is ultimately about extracting resources and creating debt through mechanisms that are backed up, as they like to say politely, by the use of force. Even using the word ‘force’ is kind of naturalizing it, making it sound like a force of nature, when it really just means that some guys are going to beat you up.

Banks are the ultimate symbol of this. Over the course of the last twenty to thirty years there’s been this proliferation of local bank branches, which don’t seem to serve any obvious function. It used to be you had banks every twenty blocks or so, and they looked like Roman temples, they were there to give you a sense of awe when you come in there. Tiled floors, Corinthian columns and so on. But it was an occasional thing.

Now they have these banks that are basically ATM outlets, but they have a couple of people working there anyway. And they look like something made in a 1980s virtual reality game, when everything was incredibly stripped down and simple. There’s no reality to it. And the only real things in there are – aside from the humans – are numbers and guns. Computers screens and people with weapons, every two blocks, a kind of symbols of this reality we now live in.

The other thing that really struck me is that the ATM machines are the only things we have – in the American society especially – that always work. Somebody pointed this out in 2000, when you had the hanging chads controversy during the Bush/Gore election. We were discussing the failure rate of voting machines, and apparently all voting machines have somewhere between 1.5 per cent and 0.5 per cent error rate, which in itself is enough, if they’re not random, to swing elections. But the point that someone made was that ‘wait, we only do this once every four years, how hard is it to get it right?’ This is the ultimate sacrament of our democracy – okay you have to do what the guy says every day, but once every four years you have a say about whether we have the right guys telling us what to do. It’s the very substance of our freedom. And yet they can’t make the voting machines good enough to get a better than 1 per cent error rate.

Yet at the same time every single one of us goes every single day to an ATM machine, so there are 200 million transactions done every day with a zero per cent error rate! When was the last time you went to the ATM and it gave you the wrong amount of money? It never happens. You don’t even count the money because it’s always right. So what does that tell us about our set of values?

We go on the escalator to get to the London Underground, and it’s broken half the time, the bridges are broken half the time, this doesn’t work, that doesn’t work, things are falling part, things are ugly – except for the ATM machines. Those always work. So it gives you a sense that financial abstractions are actually the only things that are real.

How do you get from this to actual political action. If you ask a Marxist, ‘what do we have in common, on which to build a political movement?’, they’ll say something like, well, there’s the shop floor, there’s the fundamental alienation from labour that everybody feels, and if people realize that, then they get together and you have a revolution. So how do you get from analyzing the morality of work to what needs to be done?

When I look at work and debt, I look at them because I think they are the greatest impediments to mobilizing people. It strikes me that those are very weak obstacles. If you have to fall back on these notions of morality – that anybody who doesn’t pay back their debts is a bad person, and anybody who doesn’t work or doesn’t work with something they don’t actually like is a bad person – it’s because you’ve run out of other arguments.

It used to be that people had some pretty strong arguments for why capitalism is better than any conceivable alternatives. They used to say, well, capitalism creates inequality but the rising tide lifts all boats. Even if you’re poor, you can be reasonably sure your children are going to be better off than you are. Or they said that capitalism enables rapid technological growth, and that’s going to be making our lives betters. Or that capitalism creates stability, it creates a strong middle class, and so you don’t have to fear unexpected political shocks and changes, and you get a stable, predictable world.

Now it seems that all three of these arguments are extremely hard to make. It seems very clear that the general condition of people at the bottom is getting worse and not better. We don’t have political stability, and technological advances of the kind people were used to from the nineteenth century to about the 1950s seems to have fallen by the wayside. A new iPhone is just not comparable to running water or an airplane. It doesn’t improve your life in the same way. People have pointed it out using the ‘kitchen test’, where up until the 1950s about every decade you had an invention that would totally transform the way you cooked and cleaned. Well, not any more. Kitchens have remained pretty much the same. Except for microwaves.

Plus there are a whole lot of innovations that are making life worse for a great number of people.

Right. What did you have in mind?

For instance, robots, the fear that automation is going to innovate away the last entry-level, basic-qualification jobs that pay a decent wage.

That’s an interesting point about the robots, it is a very strange reflection of our economic system that the prospect of unpleasant work being eliminated has now become a problem. It’s a sure sign that your economic system is pathological if it cannot handle that.

So this is why these moral arguments have to be made – because they’ve run out of pragmatic arguments. And I don’t think we need to have a particular reason to be able to rally people, because this assumes that people think things are basically okay, unless given a reason to think otherwise. I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think the Occupy! movement in America showed that very clearly, that people don’t think things are okay at all.

There was a really interesting study of this in the case of peasant revolts. The question for historians was that what it is that you’re trying to explain when you’re debating why did this revolt happen in 1525 in Germany or in 1387 in England? For many people, the question was ‘why were the peasants angry? What were the grievances that drove them to revolt?’ Gradually, other historians came and said that this was the wrong question. Because the peasants know they’re screwed. They’re structurally in this position where they are basically self-sufficient, but then these other people come and take away their stuff. I don’t think you need to ask why the peasants were angry, you need to ask, why did these peasants think that unlike all other peasants who have risen up, they might not get completely massacred? Why did they think they could get away with it? So for instance, with the German revolt, it was really due to the spread of new military technology that made the peasants think they could take on the knights and win. They did not need a reason to revolt, they had had a reason to revolt for at least five hundred years.

I think we are more in a situation like that. People don’t like the existing system, they just haven’t yet been convinced that a viable opportunity is out there. They don’t think they would be allowed to create the kinds of institutional structures to create one themselves. I think most people are deeply dissatisfied.

I think the major way ideology works today is not by convincing people that things are basically okay, that the system basically works. I think most people realize that the system does not work. Ideology is in convincing people that they are the only ones who have figured it out. It convinces people that everybody else believes in the ideological model. If all the people who think that they’ve figured out that the system is rigged, met all the other people who also believed that, they would probably change their mind.

Published 9 May 2017

Original in English

First published by Vikerkaar 4–5/2017 (Estonian version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Vikerkaar © David Graeber/ Aro Velmet/ Vikerkaar/ Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

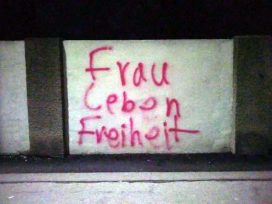

The imprisoned Belarusian opposition politician Maria Kalesnikava has been in a critical condition since the end of November. In October she was awarded an honorary professorship at the University of Salzburg. The philosopher Olga Shparaga, a fellow member of the exiled Coordination Council, pays tribute to a feminist legend.