Born in the ’80s in eastern Europe, I grew up among unkept promises which everybody refused to be accountable for. We were told we were going to be free. ‘It’s a free country!’ was a catch phrase in my pre-school, when fighting over toys. The Pet Shop Boys were played on the radio all the time, encouraging us to ‘Go West where the skies are blue’.

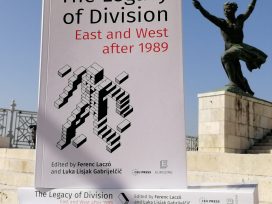

The Soviet Army memorial in Sofia, Bulgaria is going West. Photo source: Flickr

I remember adults engaging in heated debates, and I recall the angst that surrounded this. We were so-called ‘very average people’. We had relatives who had experienced their fair share of political repercussions for participating in the 1956 revolution as teenagers, or who had spent time in prison for refusing a marriage offer from a high-ranking party official. In this sense we were indeed quite average.

Although I didn’t know all these back stories, the uncertainty of my elders about whether they should allow themselves to voice what was on their minds was tangible. They were talking freedom, but they could never be sure whether it would be held against them.

A decade later, when first engaging with politics, this freedom was often used to silence us, the ever dissatisfied youth. When questioning whether representation was actually working, for instance in municipal politics, we were told that we had no idea about the freedom we had, and that we should be grateful and shut up.

We had long discussions over whether to identify as eastern, central eastern, or central European. I never actually understood why we were supposed to be ashamed of being from the East. We learnt English from cartoon channels, read French and American novels in state socialist Cheap Library editions, and prepared to ‘make it’, while suspecting that nobody would care if we didn’t. We protested neoliberalism and neocons, while having to find our way in structures not designed for us to thrive.

So when the economy came crashing down in 2008, many of us easterners felt a sense of confirmation that we hadn’t been crazy to expect this to happen one day.

Even if we put aside the inevitable tension between the generations, it was a bitter experience for many who had so eagerly wanted to believe the promises of ’89, but were then faced with the realities of western capitalism when it took over our weary yet still somehow naive regions. With illiberalism now in bloom, it is even harder to listen to people talk about our countries with the concerned and condescending tone that we recognize from back during the Cold War.

The bitterness is justified, and criticism must be thorough, even after all this time. But we must not fall into a one dimensional narrative of Untergang. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the transformation of European politics in the three decades since the fall of the Soviet empire, Eurozine has launched a new focal point. The Legacy of Division marks the 30th anniversary of the proverbial ‘end of history’. Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič, editor of Slovene journal Razpotja, and the Hungarian historian Ferenc Laczó, have curated a series of analyses from a wide variety of regional viewpoints and academic disciplines, which we will be publishing throughout the year.

For all those who, like me, are reluctant to once again remember ’89: I hope these reads will change your mind, if only a little.

Réka Kinga Papp

Editor-in-chief

This editorial is part of our 5/2019 newsletter. You can subscribe here to get the bi-weekly updates about latest publications and news on partner journals.