Flooding the zone

As a useful contribution in Foreign Policy argued, the new propaganda thrives best under democratic conditions. It functions by diluting rather than dominating the uncensored informational space. Or, in Steve Bannon’s memorable words: by ‘flooding the zone with shit’.

Whether all disinformation spreaders are Bannonite neo-Leninists is another matter. A new study by the Centre for Media, Data and Society at Central European University reveals a more mundane reality: that the majority of disinformation exists solely in order to make money.

Comparing fake news websites in five eastern European countries, Judit Szakács describes a desperate business based on fathomless credulity and the micro-margins of the click economy.

Inevitably, Facebook emerges as the crap peddlers’ platform of choice – because it allows them to get around Google’s quality criteria for its advertising services. Apparently, in the underground trade in Facebook pages, the most sought-after demographic are women over fifty, who are considered ‘adblock free’. Was this what Zuckerberg meant by ‘bringing the world closer together’?

If Boris Johnson has his way, the BBC could soon be running ads too. The Beeb is a perennially embattled institution notorious for its culture of managerialism and risk-aversion. Recently, however, criticism of bias from both right and left – some of it justified, the majority motivated by self-interest and ideology – had been hitting new levels.

After the Tory election victory in December, the government escalated its anti-BBC rhetoric, in combination with a more adversarial, not to say Trumpian approach to the established media. The BBC’s future looked genuinely uncertain.

And then came the pandemic. The Beeb’s ratings soared as trust in other media dropped. All of a sudden, government ministers were tripping over themselves to commend the broadcaster’s public spiritedness.

It has been quite a U-turn. But the real question is whether the national emergency has changed attitudes fundamentally, writes Rachael Jolley, the editor of Index on Censorship. Though too early to say, it is certainly hard to see how, after the crisis, the government will be able to revert to pre-corona hostilities.

It can be debated how far public service media institutions like the BBC meet the standards of democracy. But at a time when attacks on them belong to the standard repertoire of the far-right, they must be defended.

In Algeria, the situation is the exact opposite. After last year’s Hirak – the democratic movement that prevented Bouteflika running for a fifth presidential term – the country’s public media have embarked on a process of democratization denied to them ever since the formal inception of plural democracy over thirty years ago.

In the journal NAQD, Hakim Hamzaoui describes how bureaucratically enforced adherence to the government line had demoralized journalists at Radio Algérienne and undermined public trust. Whether the broadcaster can reinvent itself in the post-Bouteflika era will be crucial to the legacy of the Hirak.

If we want to understand what is really at stake in the politics of public service media, it is contexts such as the Algerian one that we need to be looking at.

This editorial is part of our 8/2020 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 30 April 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Measures such as ‘ethical AI’ and ‘good data’ will not bring about social justice, end racial capitalism or forestall climate disaster. How to channel discontent and counter-hegemony into an actual transfer of power in the late platform age?

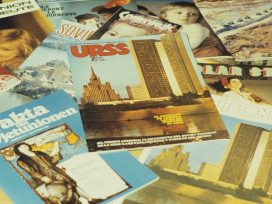

The effectiveness of Kremlin propaganda is based on a tangled bundle of lies and half-truths. Reality, however, cannot be distorted forever. As Europe needs to bring vision back to politics, can Russians finally emerge from their echo chamber?