Late to the party

I was going to write a fiery editorial for Women’s Day about how the pandemic has eaten up women’s time and energy, reversed a decades’ worth of gains and undermined the presence of women in academia and media – but then I ended up homeschooling instead. Good thing Viktor Orbán not only presented mothers with school closures for 8 March, but also made sure to keep flower shops open for just that day.

Ghada Amer: Love Has No End at Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum. Photo by ego technique from Flickr. Adaptation: Eurozine logo and colour filter has been placed over the image.

I started writing women’s day opinion pieces back at university, first for a students’ magazine that needed to fill its pages and couldn’t care less for content. Growing up in Hungary in the ’90s, this festivity meant barely more than a suffocating carnation on schoolgirls’ desks once a year.1 Mischa Gabowitsch observes a similar function: ‘Both in Russia and Ukraine, it is primarily an occasion for asserting a traditional view of the role of women by presenting them with flowers’.

The Soviet era’s take on women’s liberation was strikingly similar to current day misogynist talking points: women have been declared equal, suffrage was granted – as if it had meant anything in the Soviet empire –, so this fight is over, ladies, you have nothing more to complain about.

In fact, I only realized from some historical reading that Women’s Day had real political potential in the fight for equality. Ever since I first tried my luck reclaiming it in a public space that only allowed feminist voices as a comedy element in debate, I have been met with this exact attitude. It took years to discover that the institutions I knew and had learnt to be hollow, like trade unions, social benefits, and even elections, were not inherently useless, but intentionally hollowed out.

I started elementary school in 1990, and never understood why adults who visited my class would say with a weird emphasis: ‘So you guys didn’t learn any Russian, huh?’ We were six and had no idea about the significance of Russian classes being swapped for English ones. Neither did we suspect that many of the political processes and institutions laid out before us were merely window dressing for a new showcasing of old charades. It would take decades of dissecting to realize that democracy and equality and their regional re-iterations have no common recipe; in fact, they are capable of containing varying degrees of delusions and traces of meaningful promises at the same time.

Karl Gauffin examines an example of this kind of hollow recognition, drawing on the lessons that should have been learnt from the HIV/AIDS crisis – and the ones that ended up abused for propaganda and rainbow-washing. Recognition has been strategically important for LGBTQIA+ people in the historic fight for equality, as well as in their struggles with HIV/AIDS and the stigma associated and burdened on them because of it. But performative recognition in corporate ad campaigns is not the revolutionary tool, Gauffin points out, needed to tackle marginalization and very real needs and necessities.

Likewise, the recognition of care work and health care professionals has been a recurring topic in public discourse since the start of the pandemic, but ‘clapping for caring’ offers little help or ease from the pressure on professionals to put up with the impossible strain and difficult circumstances merely out of a militaristic sense of duty.2 The performance of recognition is a cheap way to avoid real advancements in a field populated in high numbers by women and in a large proportion by skilled migrant workers throughout Europe.

So approximately fifteen years – plus a few weeks, as it has been difficult to find the time – after that first article I wrote about what Women’s Day should mean I’m sitting at the kitchen table, rushing to scribble down my thoughts before all the kids wake up. And I just can’t stop thinking about why in health care as well as in education and other crucial institutions, capacity is usually kept to the lowest possible point and calibrated to the greatest pressure individuals can actually bear.

In case you are wondering, what exact consequences follow when, for instance, health personnel are understaffed, rushed and struggle with permanent scarcity, Aro Velmet offers an insight into how a French colonial yellow fever vaccination campaign went horribly wrong in Africa, potentially costing thousands of lives.

In my recurring complaints from Budapest, I tend to point out painful mistakes the current Hungarian regime makes, but this one, as many examples show, is not unique to its illiberal reign. Cost-cutting by overburdening those who are already under great pressure is a generic neoliberal trick, one that has greatly contributed to the worldwide crisis we are in right now.

This editorial is part of our 6/2021 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Ironically, a red carnation was the symbol of the Hungarian Socialist Party, which itself demonstrates how much the post-Socialist realm was over anything social. Nobody likes carnations in Hungary anymore.

Even the expression ‘frontline worker’ invokes a battlefield where heroic glory is offered to those who are likely to fall there.

Published 31 March 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

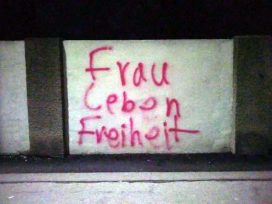

Allen Risiken zum Trotz

der Kampf für die Demokratie

The imprisoned Belarusian opposition politician Maria Kalesnikava has been in a critical condition since the end of November. In October she was awarded an honorary professorship at the University of Salzburg. The philosopher Olga Shparaga, a fellow member of the exiled Coordination Council, pays tribute to a feminist legend.