The legacy of division: dual book launch

Watch the discussion of authors and curators #EMCJ31

What is racism against eastern Europeans? And what did Viktor Orbán learn from Slavoj Žižek?

In public perception, eastern European Jewish thought is shrouded in mysticism. The intellectuals Martin Buber, Joshua Heschel, and Emmanuel Levinas shared the eastern European Jewish experience, an education in existential philosophy in Germany, and the ordeal of witnessing the mass murder of Europe’s Jews. They share a universalistic ethic aimed at promoting direct human responsibility. Above all, it is Levinas to whom we owe an appreciation of what one could call “eastern European Jewry”.

In public perception, eastern European Jewish thought continues to be surrounded by an almost mystical veil. Particularly after the systematic murder of at least three million Polish Jews by National Socialist Germany, the perception of this culture is accompanied by a justifiable sense of irreparable loss. An outward sign of this melancholy, which is never precisely specified and often borders on kitsch, is the playing of klezmer music at any suitable – or indeed unsuitable – occasion.

“Eastern Jewry” is itself a culture that is still seen as a mixture of nostalgic perceptions regarding impoverished shtetl life and the sometimes nebulous sayings of miracle-working rabbis. This narrow point of view fails to do justice to the reality of this destroyed culture, to the fact that at least just as many Polish or indeed Russian and Romanian Jews lived in large cities, that – in addition to the largely Hassidic miracle-working rabbis – eastern European Jewish culture also had at its disposal the intellectually demanding philosophy of the misnagdim, a Vilnius-based school of rational, even rationalistic interpretation of the Talmud. Also overlooked is the fact that a part of eastern Europe’s Jews joined reform Judaism, that they created Socialist mass movements – including a Yiddish-speaking trade union, which strove for cultural autonomy, the General Jewish Labour Union (the Bund), and a Zionism that aimed at Socialist self-realisation – and that a large Jewish underworld also existed, as did an entrepreneurial and capitalist class that was anything other than weak.

The colourful spectrum that emerged from the cooperation, coexistence, and competition among these extremely different classes, groups, ideologies, and schools of religious thought has been preserved mainly in the novels and shorter works of the Nobel Prize winning author Isaac Bashevis Singer. Due to its complexity, this spectrum is ill-suited for simplified views aimed at mystical edification. Judaism, not least in its eastern European forms, was the expression of a profound economic, cultural, and political modernisation process that has provoked some historians to claim somewhat audaciously that the twentieth century was a “Jewish century”.1

“Eastern Jewry”, first and foremost, was the perception of a Judaism “to the east”, namely to the east of Germany, where Jews had been granted equal civil rights following the establishment of the German Reich (1871).2 With regard to Jewry, east of Germany in 1913 meant Galicia, which was ruled by the Austro-Hungarian Empire; areas under Russian rule, including Poland, Ukraine, and Russia west of the Urals; and the Danube principalities, meaning Romania and parts of southern Hungary. Up to 1913, “Eastern Jewry” was also a form of Judaism characterised by its own language, a separate Jewish idiom, Yiddish, which originated from Middle High German and incorporated words borrowed from Hebrew and the Slavic languages.

Ultimately, this form of Judaism to the east of Germany was considered to be the epitome of an unenlightened, obscurantist, superstitious form of the Jewish faith, and was to be resisted or enlightened. On this, enlightened national Jewish intellectuals (such as the historian Heinrich Graetz), liberal philosophers (such as Hermann Cohen), and neo-Orthodox spiritual leaders (such as Samson Raphael Hirsch and his successors) were of the same opinion. The “Eastern Jewry” was regarded as a problem child, the defenceless victim of anti-Semitic pogroms and excesses, the source of a never-ending stream of immigrants who flooded the major population centres of central Europe – Vienna, Berlin, or Hamburg – from whence they travelled on to the United States or Canada, and to a far lesser extent to Argentina or to Ottoman-ruled Arz-i Filistin, the land of Palestine.

The crisis of the First World War and the bankruptcy of bourgeois-enlightenment culture, the experiences of the German Jewish soldiers in Poland and Russia with their peculiar “tribesmen” behind the front, and the emerging failure of assimilationist Jewry against the backdrop of growing anti-Semitism produced a change in attitudes. What had previously been considered dangerous – Jewish revolutionary efforts, be they Socialist or Zionist – was now regarded as an articulation of hope. What used to be seen as obscurantist nonsense – Hasidism – appeared as the locus of living holiness that had been misunderstood for too long. What had formerly seemed repulsive and vulgar – Yiddish – now became the epitome of a poetic and sensitive language.

But what was considered “especially Jewish” was hardly more than a kind of intellectual trend cultivated by Jews and at the same time adopted by the entire German intelligentsia after the First World War: an enthusiasm for the feeling and thinking of Russian culture, which was “non-Western”, if not downright “anti-Western”. From the early poems of Rainer Maria Rilke to appraisal of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s work among ethno-nationalist circles; from enthusiasm for the Russian Revolution (for example, Ernest Bloch’s The Spirit of Utopia), to the melancholy of Cossack ballads sung around the campfires of the German youth movement, whether Jewish or non-Jewish – Russia was seen as the reservoir of a revolutionary new world orientation.

The three Jewish thinkers examined here – Martin Buber (1878-1965), who focused on dialogue and encounter; Emmanuel Levinas (1905-1995), who promoted an unconditional human responsibility; and Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-1972), who concerned himself with God’s questions to humanity – were shaped by this constellation just as much as they helped shape it – at least within Jewish intellectual movements. Above all, however, this constellation had a profound and formative influence on their thought and philosophy. These “Eastern Jewish” philosophers were essentially trained in Germany, in the Germany of dialogue and existential philosophy, a philosophical climate that was by no coincidence fascinated and overshadowed by the thinking of Martin Heidegger.

It is also striking how these “Eastern Jewish” philosophies influenced and enriched those philosophical and political cultures in which their protagonists were active, be it Buber, the “Habsburg intellectual” whose influence was probably greater in Germany after the Second World War than in Israel, the country in which he lived and taught; Levinas, the Lithuanian-French moralist, whose work increasingly emerged as the secret background for “new philosophy” and “deconstruction” once structuralism and Marxism had come to an end in France; or Heschel, the “spiritual leader” whose existentialist-progressive convictions were to propel him to the forefront of the civil rights and peace movements in the United States of the 1960s.

In all three cases, the “Eastern Jewish” experience, existential philosophical thinking, the mass murder of six million European Jews, and the contemporary conflicts in the countries where they lived in their later years, merge into a framework of thought combining a universalist ethic promoting direct human responsibility with clear reference to the “Eastern Jewish” legacy. However, it must be asked whether this clear reference to the “Eastern Jewish” legacy is more than simply an expression of “imitated substantiality” (Jürgen Habermas), whether this legacy has in fact been recently invented, and whether the thought set in motion by these three philosophers really does justice to the “Eastern Jewish” legacy or at least one of its characteristic and distinctive elements.

Martin Buber was by no means always interested in Hasidism. Born in Vienna in 1878, he moved to Lemberg (today L’viv, Ukraine) in 1881, where he grew up in the house of his grandfather, an enlightened, rationalist academic who interpreted and edited rabbinical and Talmudic scriptures. Buber probably saw a Hasidic group for the first time in Sadagora (today Sadhora, Ukraine), a town in Austrian Bukovina, when he was 14. Years later, in 1918, when he was 30 and living in Heppenheim in southern Germany, he described this experience as follows:

The palace of the rebbe, in its showy splendor, repelled me. The prayer house of the Hasidim with the enraptured worshipers seemed strange to me. But when I saw the rabbi striding through the rows of the waiting, I felt: “leader”, and when I saw the Hasidim dance with the Torah, I felt: “community”. At that time there arose in me a presentiment of that common reverence and common joy of soul are the foundations of genuine community.3

However, as a student in Vienna, Buber was above all drawn to other thinkers. Buber was attracted by the work of Friedrich Nietzsche.4 as much as that of Nietzsche’s follower Micha Josef Berdyczewski (Mikhah Yosef Bin Gurion),5 whose achievements included the publication of a compilation and readable summary of Jewish sayings. A year of study in Zurich and Theodor Herzl’s work stirred Buber’s enthusiasm for Zionism, but his dissertation was a conventional one: “Contributions to the history of the problem of individuation” (Beiträge zur Geschichte des Individuationsproblems), which was submitted in Vienna in 1904. After two years in seclusion, Buber published The Tales of Rabbi Nachman (Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman) in 1906. In retrospect, Buber saw his studies on Hasidism during that period of reclusiveness as a path to conversion and enlightenment. In 1918, by then 40, Buber wrote of himself at age 28:

The primally Jewish opened to me, flowering to newly conscious expression in the darkness of exile: man’s being created in the image of God I grasped as deed, as becoming, as task. And this primally Jewish reality was a primal human reality, the content of human religiousness. Judaism as religiousness, as “piety,” as Hasidut opened to me. The image out of my childhood, the memory of the tsaddik [spiritual leader – ed.] and his community, rose upward and illuminated me: I recognized the idea of the perfected man. At the same time I became aware of the summons to proclaim it to the world.6

After The Tales of Rabbi Nachman, additional works followed in rapid succession: The Legend of the Baal-Shem (Die Legende des Baalschem, 1907); Ecstatic Confessions (Die Ekstatischen Konfessionen, 1909); a translation of sayings and parables by Zhuangzi (Reden und Gleichnisse des Tschuang Tse, 1910) with an epilogue on the teachings of Tao; a volume of Chinese ghost and love stories (Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten, 1911); a collection of speeches on Judaism (Drei Reden über das Judentum, 1911); Daniel: Dialogues on Realisation (Daniel – Gespräche über die Verwirklichung, 1913); and an extended translation of the Finnish national epos Kalewala (1914). It is clear that Buber was not only interested in exploring Judaism in a narrow sense, but in tracing a certain type of holistic, mystical experience in its various cultural articulations. What was ur-Jewish turned out to be ur-human, a road to experience and enlightenment, which was attainable by all human beings – perhaps most clearly in Hasidism.

After the First World War, which Buber clearly hoped would end in victory for Austria-Hungary and Germany,7 the story “Der große Maggid und seine Nachfolge” [The Great Maggid and his succession, 1921] appeared, followed by “Das verborgene Licht” [The hidden light, 1924]. These were then published in a compilation in 1928 and appeared in expanded form in 1938, when Buber was already living in Palestine. In 1949, all of the Tales of the Hasidim (Erzählungen der Chassidim) were published in German. Buber explained in the introduction to this book that he was consciously writing about “my re-telling of the Hasidic legends”.8 As collector and compiler, he was most aware that the source material was unreliable and based on “fervent human beings”, so that the stories of miracles can be regarded as “only” an expression of enthusiasm, as stories about things “which cannot happen and could not happen in the way they are told, but which the elated soul perceived as reality and, therefore, reported as such”.9

Buber’s Tales of the Hasidim are, in his own words, his own personal “re-telling” of the fervour among the followers of a charismatic rabbi that is not even based on reliable sources. This re-telling consists above all in giving the anecdotes and novella-like short stories “the narrative structure that they lack”.10 Even so, research on Hasidism – subjecting the sources to historical and critical scrutiny – had already been underway since the 1890s at the latest, when the leading Jewish historian Simon Dubnov published six articles on the history of Hasidism in a Russian Jewish monthly. In 1931, re-worked versions of these articles appeared in a two-volume compilation published in Berlin.11 In a supplement to the first volume, Dubnov acknowledged 193 source editions, including Buber’s work, which he discussed in detail and assessed in a balanced way. Summarising Buber’s life work – Buber was by then 53 – Dubnov wrote:

The thought arises that [Buber] himself could be the subject of the final chapter of the history of Hasidism, that of neo-Hasidism. From him the legendary “reality” of Hasidism’s creators emerges ahead of the true reality, which can be explained by academic criticism. Buber’s books are therefore suitable for promoting contemplation and speculation, but not research. They do not broaden our knowledge, but merely enable deeper psychological empathy. They represent a new and thoroughly modern commentary on Hasidic teachings.12

Buber, who spoke Polish, spent the first 13 years of his life in an upper middle-class household in the metropolis of Vienna and the subsequent 11 years in the equally upper middle-class household of his grandfather in the East Central European city of Lemberg. He studied in Vienna, Leipzig, and Berlin, then in Zurich and again in Berlin, and finally – between 1919 and 1938 – lived in Heppenheim and taught in Frankfurt, from whence he emigrated to Jerusalem in 1938. He remained there until his death in 1965. Apart from his brief childhood experience in Sadagora, Buber never lived in eastern European Jewish surroundings. There is nothing to suggest that he ever sought any personal contact with mystics or Hasidim or with their rabbis and tsaddikim – as was the case with Dubnov and the historian and philosopher Gershom Scholem.

However, between October 1941 and October 1942, Buber’s story “Gog and Magog” appeared in a Hebrew newspaper, the central organ of the Zionist trade unions in Palestine, then still under British mandate. The subject of the story was the possibility of a mystical influence on the politics of Russia during the Napoleonic War. It was written at the height of the Second World War, months before Britain fended off the German Afrika-Korps, whose victory would have exposed the Yishuv – the Jewish population of Palestine – to the same fate suffered by the Jews of eastern Europe.

Here, Buber describes for a second time direct contact with Hasidism – even if it was only on a visit to his son behind German lines in Poland during the First World War, when he was able to “familiarize myself with the area in which this battle [between two Hasidic schools, M.B.] took place”.13 This experience, he explained, had enabled him to consider recording the story, even if – later in Jerusalem – what ultimately compelled him to complete the repeatedly postponed project was an “objective factor”:

the beginning of World War II, the atmosphere of telluric crisis, the dreadful weighing of opposing forces and the signs of a false Messianism on both sides. The final impulse was given to me by a dream-vision of that false messenger spoken of in my first chapter, in the form of a demon with bat’s wings and the features of a judaized Goebbels.14

The world of the Hasidim and their spirits were an object of projection, a stage, the figures of a vast global theatre where the philosopher, who regarded himself as existentialist, gave form to his conflicting principles. The “Eastern Jewry” of Buber’s Hasidim, as it has become known since the 1950s, especially in postwar Germany, thus proves to be – and this is no small matter – a fiction, the fantastic notions of a talented philosopher of language with great powers of imagination, of a “religious intellectual” (F.W. Graf) who was not even remotely concerned with participating in the way of life that he glorified so poetically; and who – and this is also not without significance – did not see this way of life as having a promising future. Appraisals of his work that naively assume the existence of a distinctively Hasidic “conception of man”15 culminating in individual value and perfection confuse against better judgement Buber’s own ethic with the very different ethic of the historic Hasidim. Was it possible for somebody who was at least a kindred spirit to Buber – somebody who projected the image of a modern intellectual during his studies in Berlin and a nineteenth-century Hasidic rabbi during the American civil rights movement – to avoid such false appraisals?

Abraham Joshua Heschel, who invited the 30-year-old Buber from Berlin to Frankfurt’s Free Jewish House of Learning in 1937, really did come from the Hasidic milieu that had purportedly fascinated Buber so much. In 1973, Heschel’s widow Sylvia, a concert pianist from New York, published a study by Heschel on the Hasidic rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotsk, which he preceded with a brief introduction entitled “Why I had to write this book”. Here, Heschel tells the reader not only that he was born in Warsaw, but that in his early childhood he lived in Medzhybizh (Yiddish: Mezhbizh), Ukraine, a small town where the founder of Hasidism, Baal Shem Tov, spent the last 20 years of his life.

Describing the landscape of his childhood, Heschel, who was descended from famous Hasidic dynasties on his mother’s and father’s side of the family, wrote that “every step on the way was an answer to a prayer, and every stone was a memory of marvel”. It was in Medzhybizh where, at the tender age of nine, he apparently first heard of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotsk (Polish: Kock), a spiritual leader who was to accompany Heschel throughout his life, binding him with the chains of doubt, the power of sadness, and the authenticity of dismay. According to Heschel, the Kotsker rabbi became for him an antidote to uncontrolled feelings of love, excitement, and fervour, attitudes that led to “a fool’s Paradise” that could equally become “a wise man’s Hell”.16 Some time before taking his school-leaving exam, Heschel left Warsaw and sat the exam at a gymnasium in Polish Wilno (today Vilnius, Lithuania), a secular institution. He then studied in Berlin at the Friedrich Wilhelm University and at Jewish institutions of higher education. He earned his doctorate with a work on the Biblical prophets and was ordained as a rabbi in 1934.

Heschel, unlike Buber, had known Hasidic rabbis from his own family and had thus observed them at first hand. There was for him no possibility of glorifying their lives and piety. Heschel, who remained in Berlin mainly as a teacher of adults until 1937, worked from March 1937 until October 1938 at Franz Rosenzweig’s Free Jewish House of Learning in Frankfurt.17 Following his deportation to Poland in the autumn of 1938 and a brief stay in London, Heschel finally travelled to the United States in 1940, where he lived as a prophetic poet and thinker, spiritual leader, civil rights activist, and teacher at various institutes of higher education until his death in 1972. In his later years, he became the first officially recognised Jewish advisor to the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965).18

Heschel lived for only 65 years, of which the first 30 were spent among the Jews of eastern Europe: in Warsaw, in Medzhybizh, in Wilno, and in Berlin. At the time, the German capital was a lively centre of culture for Jews from eastern Europe and served as home to no fewer than 19 Yiddish newspapers.19 Berlin’s eastern European Jewish culture never drew Buber’s attention, however. For Buber, contact with non-Jewish religious intellectuals who followed the philosophy of dialogue and existentialism or the German-Jewish Zionist and non-Zionist youth movement was in every respect more important than any involvement with the lively Hebrew and Yiddish language scene in Berlin in those years.

Heschel spent the second half of his short life in the United States, where he became a leading figure of a type of neo-Hasidism only possible in that country.20 In fact, Heschel was by no means the only Eastern Jewish religious intellectual who was to leave his mark on the development of Jewish life in the United States.21 The lives of all those Jews who had been deeply influenced by eastern Europe in terms of culture, language, and religion and then found themselves in the United States were characterised by a deep antagonism. On the one hand, they had been left with no other alternative but to adhere to modern western culture; on the other, they considered it essential that they remain true to their experiences of childhood and youth. The upheaval, which was far more than simply external or geographical, required that they re-invent this past. Heschel, who wrote in English just as fluently as he did in Hebrew and Yiddish, felt that he was no longer in a position to pursue this way of life, although he was an observant Orthodox Jew and undertook his own efforts to modernise Hasidism. During the 1950s, a student who Heschel had expressly recommended spend the Sabbath with the strictly Orthodox Satmar Hasidim in the Williamsburg neighbourhood of New York City asked his teacher:

Why, if he envied me my weekend there, as he repeatedly said, did he not go to live in Williamsburg himself. “I cannot,” he replied. “When I left my home in Poland, I became a modern Western man. I cannot reverse this.”22

This modernity found unique expression in Heschel’s piety and the fact that, alongside Martin Luther King, he became one of the leaders of the civil rights marches and anti-war demonstrations. During his later life, long time after immigrating to the United States, Heschel’s outward appearance seemed no different than that of the Satmar Hasidim among whom he no longer wished to live. His face, overshadowed by a broad-brimmed hat, was framed by long hair and a long beard. However, the road to modern American life had led through Weimar-era Berlin, where he had eagerly absorbed existential philosophy, a philologically correct knowledge of Judaism, and a radically rejuvenated Yiddish literature, before transforming them for his own creative impulses.

Unlike Buber and Heschel, Levinas, who was born in 1906 in Kovno (Kaunas), a centre of anti-Hasidic, rationalist Talmud scholarship, never wore a beard. Levinas’s parents considered themselves to be “Russian Jews”. They occasionally spoke Yiddish with one another, but only Russian with their children. Levinas later referred to works by Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky and the rationalist school founded by the Gaon of Vilna, the leading anti-Hasidic academic figure of the eighteenth century, as the formative influences of this “Russian” childhood. Levinas found a role model in the rationalist Rabbi Chaim Volozhiner, a student of the Gaon of Vilna, who, despite his general anti-Hasidic stance, engaged in speculation in the tradition of Jewish mysticism and combined personal piety, rational argument, and deliberative thoroughness..23

Levinas’s family was forced to flee when Kovno was occupied by German troops in 1915, ultimately finding a home in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Levinas, who had led a sheltered childhood and had learned Hebrew as a small boy, enrolled at a Russian gymnasium in 1916, despite restrictions on the number of Jewish pupils. As from 1919, he attended a Jewish lyceum in Kaunas, where he was impressed by the teachings of the head teacher, an enlightened German Jew who had a particular weakness for Goethe.24

After taking his school-leaving examination in Lithuania, Levinas also travelled to the West, visiting Berlin and Leipzig, though not remaining long. Instead, in 1923, at the age of 18, he matriculated at the University of Strasbourg, France, where he studied under Maurice Halbwachs, among others, paying particular attention to psychoanalysis. In 1928-1929, Levinas followed the reputation of Edmund Husserl and moved to the University of Freiburg. While there, he completed two seminars under Martin Heidegger, whom he in turn followed to Davos in 1929 for a seminar lasting several weeks, the famous Hochschulwochen. Levinas was particularly interested in the notorious debate between Heidegger and Ernst Cassirer, squarely siding with the former and making fun of his defeated adversary in a student cabaret at Davos. Levinas, who later regretted this performance, imitated Cassirer with a stammer when saying words such as “Humboldt” and “culture” and lampooned Cassirer’s pacifism.25

In the 1930s, Levinas worked for the Alliance Israelite Universelle, a Jewish educational and welfare organisation rich in tradition and was at the time actively involved in the Parisian intellectual scene. He was highly esteemed in particular for his excellent knowledge of Husserl and Heidegger. Naturalised as a French citizen, Levinas was drafted into the army in 1939, captured by the Wehrmacht, and held for more than four years at a POW camp where his Jewish origins were well known. Soon after his release from captivity, he learned that his father, mother, and two brothers had been murdered in Kovno by Lithuanian nationalists during the German occupation.

Upon receiving this news, Levinas made a decision never to set foot on German soil again. As director of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, he published more philosophical texts and took up teaching in 1961, first in Poitiers, then in Nanterre, and finally in Paris at the Sorbonne. His semi-private Talmud courses, which found inspiration in philosophy, became a secret centre of learning for an entire generation of intellectuals, just as his contacts with the Catholic Church enabled him to pioneer a Jewish-Christian dialogue based on philosophy.

In 1976, already over 70, he gave up teaching at the university. Until his death in 1995, he worked in Paris as a highly sought-after spiritual teacher, whose reputation grew from year to year. Levinas, however, credited his own Jewish education not to the memory of the religious setting of his childhood, but to Monsieur Chouchani, a Sephardic Jew who was as obscure and fascinating as he was learned and irritating, a Talmud scholar who roamed the earth like the cliché of the Eternal Jew. The polyglot Chouchani was probably born in Marrakech and wandered between the continents without a home or fixed address before dying in Uruguay.26

Levinas almost lived to be 90. The first 17 years of his life were spent in eastern Europe, and he was never to return there. His intellectual career led him to Strasbourg, Freiburg, Davos, and Paris. In contrast to Buber and Heschel, the eastern European Jewish background that may have helped shape his views was not Hasidism, but Talmudic rationalism. Levinas was also deeply influenced by existential philosophy and its precursors: what Nietzsche was for Buber and Soren Kierkegaard was for Heschel, so Edmund Husserl and Heidegger were for Levinas. After 1945, Levinas was to dedicate his philosophical life to refuting Heidegger’s un-ethical, indeed anti-ethical thought. Prepared intellectually by Russian literature, Talmudic rationalism, phenomenology, and existential philosophy, Levinas was ultimately able to develop his own Jewish thought in the narrower sense of the term after being inspired by Chouchani. Nevertheless, we can give credit to Levinas – unlike Buber and Heschel – for a clear appreciation of that which could be defined as “Eastern Jewry”.

In his treatment of Rabbi Volozhiner, Levinas begins by discussing the very different way the Jewish enlightenment, the Haskalah, initiated by Moses Mendelssohn and others, was received among the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe:

From the nineteenth century onwards they in fact found themselves progressively led towards studies that were different to those of the Torah, and towards forms of what are known as western thought and life; a process into which western European Jewry had voluntarily been entering since the eighteenth century. This movement towards so-called modern life really became apparent with the Russian, Polish and Lithuanian Jews almost concurrently with the influence that can be attributed to the yeshivah of Volozhin. But while undergoing the seduction of the West and its rationalist culture, Eastern Judaism, for the greater part, remained immunized against the temptations of pure and simple assimilation to the surrounding world. It refused to treat as secondary the spiritual world of its origins, and to doubt the complete maturity of traditional Jewish culture, even when it gradually distanced itself in its way of life and intellectual preoccupations from the strict rules handed down by tradition. This faithfulness to the Torah as culture, and a national consciousness determined by this culture, remained the distinctive feature of the Eastern Jew at the heart of a Western style of life. There were, admittedly, many demographic, social and political reasons for this. But among the causes of this steadfastness, it is also necessary to include the education received in the yeshivot like that in Volozhin by the elite of these Eastern Jews. The Judaism of the Talmudic schools – or the memory of this Judaism as it persisted in families – was to protect the Jewish masses from assimilation, as it protected the Hasidic movement from schism.27

Levinas is to be amended by one exception, namely the sizable number of young Russian Jews, male and female, who in their struggle against tradition resolved to join the Bolsheviks, fought religious and Yiddish Jewry, and thus played no small part in the intellectual destruction of eastern European Jewish culture.28

“Eastern Jewry”, as we also know from its representative thinkers, is the result of a double loss and double mourning, as well as the result of re-invention. This mourning has been most precisely expressed by Heschel, who described the painful path of transition into the modern age as follows:

When we were blinded by the light of European civilisation, we could not appreciate the value of the small fire of eternal light […] We compared our fathers and grandfathers, our teachers and rabbis, with Russian and German intellectuals. We preached in the name of the twentieth century, compared Berdichev to Paris, Ger [Góra Kalwaria] to Heidelberg. Dazzled by big city street lamps, we lost our inner vision. The luminous vision that for so many generations shone in the little candles was extinguished for many of us.29

The re-discovery of that extinguished light, however, did not lead to its re-kindling. In fact, a new light was created.

Yuri Slezkine, The Jewish Century (Princeton 2005).

Trude Maurer, Ostjuden in Deutschland 1918-1933 (Hamburg 1986).

Martin Buber, "My Way to Hasidism", in idem, Hasidism and Modern Man, Maurice Friedman, ed. and trans. (New York 1958), pp. 52--53.

Paul Mendes-Flohr, "Zarathustras Apostel: Martin Buber und die jüdische Renaissance", in Jacob Golomb, ed., Nietzsche und die jüdische Kultur (Vienna 1998), pp. 225--235.

Werner Stegmaier, Daniel Krochmalnik, eds., Jüdischer Nietzscheanismus (Berlin 1997).

Buber, "My Way to Hasidism", p. 59.

Ulrich Sieg, Jüdische Intellektuelle im Ersten Weltkrieg (Berlin 2001), pp. 57--58.

Martin Buber, Tales of the Hasidim, 1, The Early Masters, Olga Marx, trans. (London 1956), p. 6.

Ibid., p. 1.

Ibid., p. 8.

Simon Dubnov, Geschichte des Chassidismus, I. & II., reprint (Königstein 1982).

Ibid., I, p. 310.

Martin Buber, For the Sake of Heaven: A Chronicle, Ludwig Lewisohn, trans. (Heidelberg 1978), p. 405.

Ibid., p. 11.

Ute Holm, "Die chassidischen Geschichten und ihre implizite Didaktik", in Martha Friedenthal-Haase, Ralf Koerrenz, eds., Martin Buber: Bildung, Menschenbild und Hebräischer Humanismus (Paderborn 2005), p. 144.

Abraham J. Heschel, A Passion for Truth (London 1973), pp. 8--15.

Ulrich Lilienthal, "Zeuge Gottes", in Werner Licharz, Wieland Zademach, eds., Treue zur Tradition als Aufbruch in die Moderne (Waltrop 2005), pp. 361--402, especially 379--380.

Maurice Friedman, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Elie Wiesel: You Are My Witnesses (New York 1987), p. 82--84.

Lilienthal, "Zeuge Gottes", p. 367.

Friedman, You Are My Witnesses, pp. 8--14.

Hillel Goldberg, Between Berlin and Slobodka. Jewish Transition Figures from Eastern Europe (Hoboken 1989).

Friedman, You Are My Witnesses, p. 9.

Emmanuel Levinas, "In the Image of God', according to Rabbi Chaim Volozhiner", in ibid., Beyond the Verse. Talmudic Readings and Lectures, Gary D. Mole, trans. (Bloomington, IN, 1994), pp. 151--167.

Marie-Anne Lescourret, Emmanuel Levinas (Paris 1994), p. 37--38.

Ibid., p. 81.

Ibid., pp. 142--145.

Levinas, "'In the Image of God'", pp. 152--153.

Slezkine, The Jewish Century.

Quoted from Lilienthal, "Zeuge Gottes", p. 365.

Published 27 November 2008

Original in German

Translated by

Anna Güttel

First published by Osteuropa 8-10 (2008)

Contributed by Osteuropa © Micha Brumlik / Osteuropa / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

What is racism against eastern Europeans? And what did Viktor Orbán learn from Slavoj Žižek?

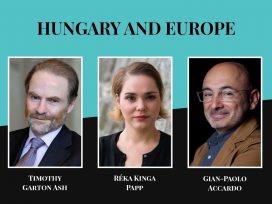

As a historian his expectations are gloomy, but as a political writer his optimism is strategic: Timothy Garton Ash talks about the European Union’s internal flaws and debates whether crises and collapses are always necessary for renewal.