Taking on imperial knowledge, cultural denial and dogmatic absolutism requires authors who can find their way around tricky narrative strategies, using their wits to juggle cultural preconceptions.

An anarchist philosopher turned right-leaning libertarian and anti-capitalist critic of the illiberal order, Gáspár Miklós Tamás (1948–2023) embodied what east European thinkers have tended to be best at: making paradoxes intelligible.

Democracy is ‘an odd thing to be glad about all on one’s own,’ Gáspár Miklós Tamás quipped in the late 1990s, and his sensation must have been reinforced in later years.

An erudite philosopher, formidable public intellectual and accomplished stylist in multiple languages, Tamás – widely known as TGM – was a prolific essayist of unique stature in Hungarian public life, preoccupied with theoretical ideas, cultural and national traditions, and revolutionary prospects. His writings typically combined philosophical insights with historical breadth to offer counter-intuitive reflections on political ideas and processes. ‘A key question is how the Marxist, critical theory of history was lost in Bolshevism, how both social democracy and Bolshevism returned from Hegel through late nineteenth-century neo-Kantians and empiricists to a radical form of positivism while forgetting even about Kant,’ he incisively pondered in one of his characteristic sentences.

A rare feat for an irreverent thinker with mainly theoretical interests, Tamás was also an insightful and fair-minded portraitist. He developed some of the most profound biographical and intellectual sketches of his contemporaries, including of people he had long been politically alienated from. Culture to him apparently meant the democratic sum of knowledge and experience, collected to counter oppression and reject stigmatization.

By inclination and commitment, Tamás was un dissident sous tous les régimes, with one crucial and much-regretted exception after 1989.

His originality manifested in manifold and intricate ways. He was socialized in what he would later describe as ‘an intellectual microcosm with a passion for learning, genuinely concerned with the downtrodden, and characterized by puritanism and altruism’. The son of former underground communists, and a baby boomer born to a Jewish mother, he grew up Hungarian in the increasingly Romanianized city of Kolozsvár/Cluj. As well as attending the university of his birthplace, he also studied in Bucharest, since ancient Greek was only offered in the capital. His father insisted that he had to master English too, ‘since poetry was especially beautiful in that language’.

Tamás soon emerged as a new leftist philosopher, a polyglot in a closed world, an eastern European ’68er from a highly educated urban milieu living under an increasingly chauvinistic ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ – one that he was inclined to perceive as fascistic. Besides the suppression of the Prague Spring by Warsaw Pact troops, the blatant support for far-right ideas under Ceaușescu’s national Stalinist regime represented a key shock in his political socialization.

A decade later, in 1978, Tamás was allowed to move to Budapest to become that rare kind of political émigré – one within the Eastern Bloc. A non-Marxist personally close to the Lukácsist philosophers, he soon started to contribute to the Hungarian democratic opposition as a left-leaning libertarian fluent in the rhetorical modes of Transylvanian Calvinism.

During his extended stays in the UK and the US in the 1980s, Tamás was much impressed by local manners and sensibilities as well as the unfolding ‘neoconservative revolution’. He returned to Hungary in the late 1980s to enter democratic politics from the position of a right-leaning libertarian, acting as the exceptionally skilled, but notoriously confrontative orator of a nominally progressive liberal party, the Alliance of Free Democrats.

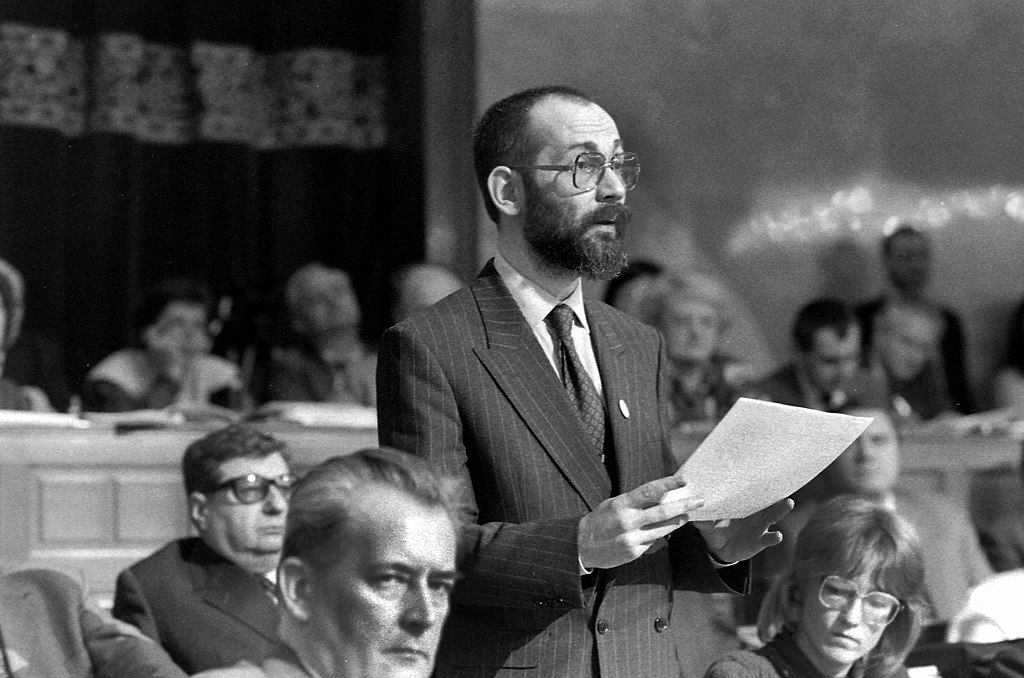

Gáspár Miklós Tamás speaking in the National Assembly of the Hungarian Parliament as a representative of the Alliance of Free Democrats in 1990. Author: Fortepan / Urbán Tamás. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

His party was briefly led by János Kis, a former ‘Marxist revisionist’ intellectual and the Hungarian translator of both Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant. Tamás, for his part, now invested his hopes in the rise of an active citizenry that would conduct passionate public debates and finally lead his chosen homeland to prosperity.

Tamás’s key goal around 1989 seemingly was to ennoble liberal democracy and make it more philosophical – which resembled the agenda of great conservative antifascist émigrés from previous generations, like Leo Strauss, Hannah Arendt, or Eric Voegelin. His multi-layered interventions in Hungarian public life were avidly contested and recurrently dismissed, but never in a neutral tone.

I remember him getting emotional in class when recalling, years later, how people held up the banner ‘Szeretünk Gazsi’ (‘Gazsi, we love you’; Gazsi being a nickname for Gáspár) to welcome him in those heady days of revolutionary change. Ironically, however, the only moment at which he experienced ‘collective joy’ and felt anything but lonely in political terms was the one he came to regret the most.

‘We’ve been criminally blind and thought, immaturely and selfishly, like many generations of victors before us, that our political success and fame meant a better deal for all. Ridiculous,’ was one of his retrospective assessments. In his more bitter moments, he would accuse himself and his cohort to have compromised ‘the idea of freedom for a lifetime by calling an end to egalitarian state redistribution to be tantamount to liberty’.

Gáspár Miklós Tamás at a political rally in Kossuth Lajos Square in January 1990 as a newly-elected representative of the National Assembly of the Hungarian Parliament from the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ). Author: Fortepan / Urbán Tamás. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

His intellectual journey into the 1990s resembled the ‘Trotsky to Thatcher’ road typical of western neoconservatives, leading him via Leo Strauss and the ‘Tory anarchism’ of Michael Oakeshott to Friedrich Hayek. Yet his preoccupation with eastern Europe and what he perceived as the grave failures of its capitalist and supposedly democratic transformation would soon motivate him to make an idiosyncratic and intriguing intellectual turn.

Around 2000, while still negatively disposed towards ‘the previous regime’, he insisted that it was the one that helped establish ‘the only modern form of civilization eastern Europe has ever known’. Tamás discovered Karl Marx, then out of fashion, whom he admitted never to having seriously read. In this respect, TGM’s trajectory was the reverse of Lukácsist philosophers turned committed liberals such as János Kis or Ágnes Heller.

In the early twenty-first century, TGM would draw on an eclectic assortment of classic leftist and contemporary post-Marxist thinkers to emerge as a critic of political economy, a vocal anti-fascist, and the most articulate and prominent voice of the anti-capitalist left in Hungary and the region. By his own admission, he would be the only east European participant at western conferences devoted to historical materialism around this time, save some (rather anomalous) Greeks.

This asynchronous – and, to many, perplexing – turn unfolded just when what TGM theorized as ‘post-fascism’ was gaining steam, almost imperceptibly at first but much more evidently since. In subsequent years, he saw ‘an ingenious old-new form of flexible and non-murderous dictatorship’ take control just a short walking distance from his apartment in downtown Budapest.

While Tamás found intellectual companions and political allies among members of the younger generations, some of whom came from neighbouring countries, including Romania, his anti-capitalist intellectual agitation – his ‘Marxist deviation’, as he half-jokingly called it – remained little more than a theoretical exercise. Fascism, he explained, was the pre-emptive counterrevolution of the twentieth century, whereas communism amounted to ‘the pre-emptive cultural revolution of our times’ – a cultural revolution that rejected all institutions, since they were all becoming more fascistic and repressive.

Tamás must have understood that he was living a somewhat anachronistic, even nostalgic life: as a ’68er, he entered adulthood during the very last stages of the modern workers’ movement, with its powerful counter-society and counterculture. His rediscovery of revolutionary socialism also meant a sort of return to the world of his greatly admired parents (one of his outstanding short essays recalled the life and pursuits of his father).

G. M. Tamás remained an intellectual authority without institutional power, a free person in a bureaucratized world, an ambitious generalist in an age of narrow specialization, a high-brow thinker amidst pop tunes and social media buzz, a philosophical critic in a society largely resistant to more abstract considerations, a morally serious person in a sceptical and cynical place, and a passionate and jocular polemicist in an increasingly stifling environment.

In one respect, he was utterly consistent: he avidly sought the possibility of philosophically grounding political action and believed, inspired not least by Christian thought, that political goals had to be defined via reflection on the sources of human suffering. In other words, his philosophizing started not from a sense of wonder but from being aghast. He was convinced that ideas had to be radical, subversive and emancipatory, and maintained his theoretical distance from the politics of the ‘lesser evil’ – social democracy, most importantly, which he could at times support out of practical considerations.

Tamás was able to discourse in an articulate and extended manner at short notice. So long as he was composing, he was also cherishing hope, he would say. He never completed monographs; his four major books, one of which was published in two volumes, were all collections, whereas his two other books contain only single essays – the samizdat A szem és a kéz (The eye and the hand, 1983) and A helyzet (The situation, 2002). His favoured form – and the one most suited to his talents – was the long essay: his range, erudition, impulsive style, touching flourishes, and ability to make surprising connections would combine here to great effect.

Tamás entered adulthood in the short years of relative regime relaxation in Romania during the 1960s – possibly the best period for Hungarian-language press, book publishing, and theatre in the country’s history. His first collection, A teória esélyei (The chances of theory), from 1975, shows an exceptional intellect at pains to effectively convey his complex ideas. At times he failed. His 1976 letter to editor Ernő Gáll, a member of the progressive establishment among Transylvanian Hungarians, is so convoluted and cryptic that it is barely comprehensible.

Perőcsény, Hungary, 1987. Gáspár Miklós Tamás with writer and critic Sándor Radnóti, and dissident János Kenedi. Author: Fortepan. Donor: Hodosán Róza. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Being banned from teaching within a few years upon his arrival in Budapest, in 1982 Tamás published in samizdat his first and (by his own admission) somewhat naive political essay ‘A csöndes Európa’ (‘The quiet Europe’), in which he propagated ‘the resurrection of the most diverse kinds of anti-authoritarian and anti-statist, liberal, democratic and socialist political thinking and practices’ – a platform so diverse that he would never manage to stray from it in the course of his life.

As part of this extended reflection, TGM envisaged a future coalition of forces that would involve the autonomists on the left, radical and moderate Christian democrats, revisionist neo-Marxists and the radical new left, and even parts of what he called ‘communist political culture’. He placed most hopes in the multi-layered heritage of the non-communist left and non-Marxist socialist traditions: radical democrats, syndicalists, agrarian socialists, social democrats and anarchists – a broad church which he considered eminently practicable, even relatively unified, as shown by the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and the Solidarność movement in Poland.

While A szem és a kéz still articulated an anarchist position, his political anti-communism and anti-statist beliefs soon made him drift to the liberal and libertarian right. His most significant essay penned in 1989 and entitled ‘Búcsú a baloldaltól’ (‘Farewell to the Left’), theorized a minimal state, legal security, the fall of ‘militantism’, and even ‘the least possible public activity’. It represented a rejection of socialism from what Tamás called a ‘modern conservative’ position.

The modern conservatism he envisioned for Hungary would cherish the national liberal past as its own tradition and help develop a new, moderate patriotism which would not be counterrevolutionary. In ‘Farewell to the Left’, TGM declared that his favourite time was the 1830s, ‘the world of Kölcsey, Széchenyi, Nyáry’ and that he felt closest to ‘the Earl Széchenyi-Baron Kemény-Asbóth type of paradigm’.

This must have sounded to many like trying to integrate a country about to exit its Soviet regime into the English countryside of an imaginary past. Yet Tamás was eager to remind that ‘Old Whig liberalism and neoconservatism’s refoundation’ in the English-speaking world were the achievement of Central Europeans such as Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Joseph Schumpeter, Karl Popper, Leo Strauss and Isaiah Berlin.

With an unusually defensive-sounding argument, Tamás claimed that while his views had changed little and his ‘libertarian prejudices’ had remained intact, he had to accept that his theoretical allies were essentially on the right. Long unwilling for emotional reasons, he ultimately admitted that on the left his ‘rigorous opposition to institutional interventions’ was only shared by ‘few charming anarchist sects’ – and that the potential German and Austrian social democratic allies of the Hungarian democratic opposition and their Polish and Czechoslovak friends and co-conspirators had betrayed them in the 1980s.

His sudden devotion to earls and barons of previous centuries was not just a fad: his more theoretical writings in those years – collected in Törzsi fogalmak I-II (Tribal concepts, volumes 1 and 2) in 1999 – were also much concerned with the rise of liberal thought in the nineteenth century and the moot questions of nationalism – and what Tamás conceptualized as its sinister Doppelgänger: ethnicism.

In 1995, he followed up with ‘Búcsú a jobboldaltól?’ (‘Farewell to the Right?’), in which he underlined how important the liberal–social democrat (or in US terms: conservative-left liberal) division was, clearly implying that he preferred the former pole. In this essay, Tamás again explicitly distanced himself from reputed ‘antiliberal radical democrats’ but also from Tory anarchism. Being ‘at least as conservative as before’, he explained that his position moved closer to ‘classical republicanism’ and included a commitment to recreate a ‘universal high culture’.

TGM now also argued that the failure of the democratic change of regime – which he understood as his own personal failure too – motivated him to critique the liberal presuppositions ‘so dear to his heart’. He asserted that market liberals and progressive or human rights liberals, though opposed to each other on many counts, all understood liberty as a way of turning away from public affairs, as ‘liberty from politics’, with all its disturbing implications. The democratic opposition of the 1980s, he argued in his English-language essay ‘The legacy of dissent’ (1993), only contributed to this regrettable ‘exit from the polis’.

Tamás now identified ‘the anti-bourgeois and anti-individualist consensus’, and ‘the reign of suspicion’ that viewed all political power as fundamentally unjust, as crucial problems in eastern Europe. He claimed that the post-Stalin period had depicted Stalinism as a revolutionary regime, so de-Stalinization logically implied inner peace, the lack of any ideology, and market reforms.

Significant as the changes may have seemed at the time, 1989 only preserved this ‘negative dialectics’, an extreme form of agnosticism manifested in a rejection of dictatorship without a real commitment to democracy. Resistance in eastern Europe bred exhaustion and antipathy, not hope and change. The anti-utopian spirit discredited what would have been needed the most, Tamás asserted, such as fierce intellectualism, magnanimity, imagination, even enthusiastic idealism, a sense of obligation, and a profound and honest love of liberal politics.

If this was an early critique of what should have become a democratic form of public life, in his much-discussed intervention ‘A posztfasizmusról’ (‘On post-fascism’), published in 2000, Tamás broadened his horizons. He argued that nation states were not only defending racial and class privileges but also the ‘universal citizenship of nationals’ against the ‘virtual-universal citizenship of all humans’.

He understood ‘post-fascism’ as a new way of separating the normative state – which increasingly applied only to the ‘core populations’ – from the prerogative state which would act arbitrarily. Integrating the philosophical, the historical, and the more directly political, Tamás diagnosed the spread of a general condition rather than the rise of a conspicuous political movement. He labelled this condition ‘an anti-Enlightenment form of liberal democracy’.

When it came to eastern Europe, TGM’s argument was simple but captivating: post-fascism could find a large audience by offering explicit legitimation for inequality, which had come to be taken for granted but not explicitly justified after 1989. Countering the more mainstream stance in his own liberal and progressive milieux, he added that the liberal, Kantian, rather paternalistic responses to post-fascism were unsatisfactory. They were affirming one kind of inequality (the competitive one) while criticizing another (the racial or ethnic one), which only undermined their egalitarian claims.

Around the same time, Tamás took a seemingly sharp turn to the left – and not only because of what he saw as the abysmal economic and social failures of ‘regime change’. He came to believe that eastern Europe was the vanguard of political reaction where capitalism appeared to be ‘the only and absolute reality’. Ironically, he thought that this was also ‘an accomplishment of communists’, who had eliminated both ‘premodern elements’ and ‘the revolutionary working classes’ in these societies.

As usual, however, his main considerations were of a more theoretical character – and had much to do with his new interest in the making and functioning of social class. He repeatedly emphasized that the question of justice, so crucial to contemporary liberal philosophies, was not among his central preoccupations. He preferred to think historically and thought that the problem with liberal reflections on capitalism was that they drew a false line between the private and the public.

Whereas politics was confined to the workplace before 1989, it was banned from it thereafter, Tamás pointed out. In his understanding, the qualification of labour as a private, contractual relationship represented a ‘philosophical scandal’. He conceded that liberalism aimed at the weakening, sublimation, or even humanization of power, but it always ‘stopped at the factory gate’.

Miklós Gáspár Tamás at the table, Gábor Demszky (former mayor of Budapest) to the right, András Lányi (film director, writer and activist) at the side. Photo by Fortepan via Wikimedia Commons.

Symmetry, equality, participation, and transparency were principles to be applied across the board, including at the workplace – whereas hierarchies of all kinds and subjugation to any authority required special acts of justification. The distributive and redistributive forms of justice liberalism propagated could not on their own lead to a free society without exploitation, oppression, authority, and knowledge monopolies, Tamás explained. All liberalism could offer as a means of reducing inequality was to strengthen the state, which inevitably led to a reduction of human autonomy.

His interpretation of recent history was that capitalism managed to survive both the bourgeoisie and the proletariat as sociocultural and political actors due to the varied forms of statism that arose in the twentieth century – from Nazi rule to the welfare states built by social democrats. Each of these forms, though markedly different from one another, either suppressed or co-opted the political forms of class struggle and thereby contributed to end ‘the classic phase of capitalism’.

Whereas modern statism made both bourgeois class culture and the international socialist workers’ movement largely disappear, corporate technocracy and state bureaucracies came to possess too much power. That transformation, Tamás now diagnosed in pessimistic tones, opened the door to ‘barbarism and chaos’.

Just as his right-leaning libertarianism of the 1980s and 1990s derived much of its impetus from his earlier anarchism, the leftist critique he later articulated was in a critical and constructive dialogue with his neoconservative phase.

TGM had emphasized during his neocon middle years that east European peoples, during their most significant political moments in recent history, consistently demanded a combination of socialism and democracy – and that he was personally committed to ‘the liberation of private life’, understood as a more ambitious agenda of emancipation. His basic vision of history as well as the transcendent goals he articulated as a revolutionary socialist sounded remarkably similar – only that his assessment of those historical episodes was reversed. Maybe illiberal radical democrats loved their country more than moderate patriots, after all?

What changed in his thinking was that he no longer believed that liberal legal and economic guarantees could achieve anything near a universal liberation of private life – rather, they were facilitating the rise of a post-fascist dual state. Drawing on post-Marxist theory, Tamás now appeared convinced that contemporary capitalism amounted to a ‘planned form of irrationality’ – and it had to remain irrational to enable ‘relative forms of freedom’ which were far from encompassing or shared widely enough.

Tamás also came to understand that the social democratic critique of neoliberalism was as valid as the neoliberal critique of social democracy. From a theoretical point of view, they cancelled each other out; hence the need to develop an alternative conceptual framework.

In his late phase, Tamás still propagated a ‘democratic road towards more freedom’. Under the present conditions, he understood freedom not as self-realization but as a form of liberation that helped one analyse why others were not free. His intellectual agenda continued to revolve around de-naturalization and historicization, and he remained strictly opposed to rationalizations, let alone apologias of suffering.

He kept on warning that a political practice aimed at a homogeneous society to get rid of the mortal sins of exclusion, humiliation, and injustice was neither feasible nor desirable. In his last essay published in his lifetime, ‘Öt tanács a hazának’ (‘Five recommendations for the homeland’), Tamás affirmed his ‘commitment without illusions’ to an enlightened, egalitarian, and antifascist European society, keen to draw on alternative sources of information and authority.

As an eclectic, original, exceptionally perceptive and stubbornly anachronistic thinker, Tamás embodied what east European intellectuals have tended to be best at: noticing profound ironies, making paradoxes intelligible, and sublimating the spirit of rebellion. He also maintained that contemporary capitalism only seemingly put an end to class struggle; what it truly accomplished was to abolish ‘the humanism of bourgeois culture’ as well as ‘the prophetic traditions of the proletariat’.

This was evidently untrue so long as G. M. Tamás was challenging, reminding and polemicizing.

Published 3 March 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine (in English); Razpotja (in Slovenian, upcoming)

Contributed by Razpotja © Ferenc Laczó / Razpotja / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Taking on imperial knowledge, cultural denial and dogmatic absolutism requires authors who can find their way around tricky narrative strategies, using their wits to juggle cultural preconceptions.

Tackling climate change requires more care. Environmentalist slogans demand respect for Mother Earth. But does it make sense to gender a planet? How should nature be perceived? And what does ‘natural’ even mean within an ecofeminist frame?