When crisis hits, vulnerable groups suffer. And sex workers, already enduring precarity, have become the scapegoats of COVID-19’s health focus, facing heavy fines, police abuse and deportation threats. Boglárka Fedorkó investigates the lessons that can be learnt from the solidarity and organization of those facing adversity.

At the beginning of March, sex worker collectives all across Europe started to receive alarming calls from fellow workers. When brothels shut down, there was a sudden drop in client numbers and an unprecedented wave of people required immediate help. Requests were even being made for food and other now basic necessities such as hand sanitiser and masks. As it was impossible to tell how long lockdowns and contact work restrictions would last, many activists looked at the pandemic with a sense of déjà vu. The global spread of HIV/AIDS had left alarming memories of how sex workers, together with migrant, LGBT, racialized and poor communities, can be scapegoated as ‘pools of infection’ instead of receiving support and protection from governments and society at large.

Since the advent of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, newspaper stories, and medical and health journal articles have often portrayed sex workers as a major influence in spreading infection. They are commonly considered responsible for the virus’s sexual transmission to ‘innocent’ heterosexual men and their wives and children. Current, mandatory health checks based on these very stereotypes and prejudices exercise an oppressive form of control over sex workers in various European countries. Many activists suspect that coronavirus may reinforce the stigma of this population as ‘core transmitters’ responsible for disseminating the virus. In reality, many sex workers across Europe abandoned the streets when lockdown measures were introduced and demonstrated a sense of responsibility for public health.

However, only a small minority could afford to stay at home and not work for weeks that ultimately became months. In the absence of governmental support and official recognition of their worker status, those in the sex industry found themselves with zero income. Many faced a hard choice between working and exposing themselves to COVID-19 or not having enough money to put food on the table.

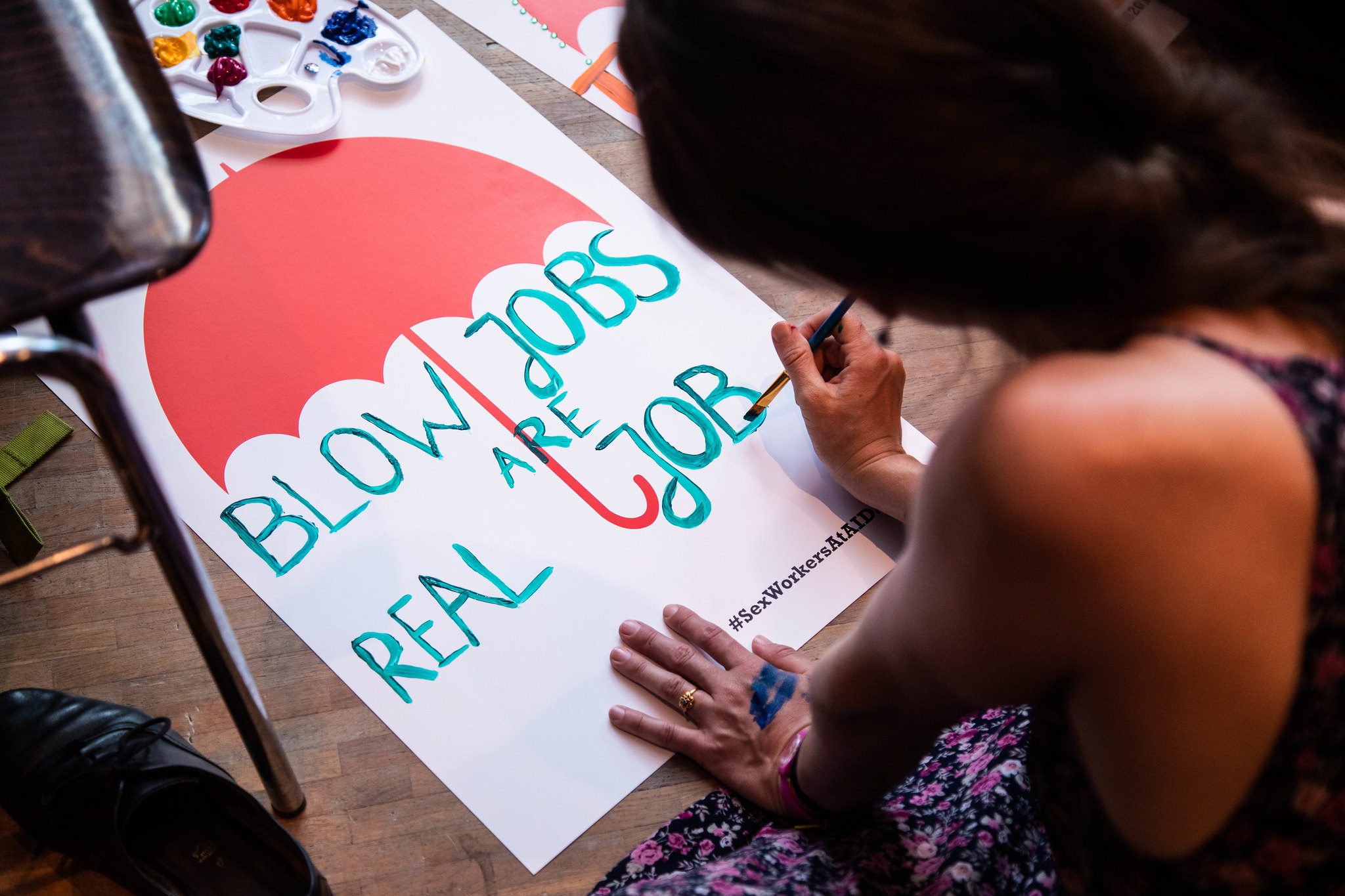

Sex workers have been fighting HIV/AIDS and demanding workers’ rights for decades. This sign was made at a pre-conference meeting of more than 150 sex workers and activists, ahead of the International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam 2018. Photo is courtesy of Juno Mac on Flickr.

From one day to another

Since its early stages, the COVID-19 crisis has provided urgency to decades of activism that already recognized sex workers forced to operate on the margins of society in precarious circumstances without the protection enjoyed by formal workers. Members of ICRSE, a European network for sex workers’ rights, reported facing a complete or near complete loss of income from one day to the next after the pandemic’s onset in Europe, with many struggling to keep a roof over their heads.

Many – in large part EU migrants and third country nationals in Western Europe – ordinarily live in overpriced brothel accommodation, which was suddenly shut down, or do not have formal rental contracts. Even though some governments introduced measures to stop evictions, this proved of little help to those in the sex industry. For example, Paradise, one of Spain’s largest brothels, was able to access governmental support to cover wages for its registered employees but could not include its sex workers in the provision; formal employment is illegal in the sex industry in Spain. Therefore, 90 women who had worked at Paradise suddenly found themselves on the street.Issues of available, affordable housing are more relevant today than ever for European societies and sex workers are especially vulnerable. Mothers who sell sex, accused of endangering their children, have to rent additional private accommodation in which to work that multiplies their regular outgoings. As renting premises for prostitution is deemed illegal in most European countries, landlords and property owners are known to charge double or triple prices that shift the potential costs of running illegal businesses onto sex workers. Isolated from their social networks, communities and families, deprived of alternative income sources and lacking sufficient language skills, migrant workers rely even more on intermediaries to manage their accommodation, resulting in very limited negotiating power.

Housing instability increases migrant vulnerability to the point of exploitation. In Spain, many sex workers spent the quarantine with clients in their homes for a reduced price or for free, as they had no other accommodation option. In Italy, local sex worker groups reported that many of their transgender and migrant members found themselves homeless at the beginning of one of the strictest lockdown in Europe, in some cases having to sleep rough. Although financial help is theoretically available to those self-employed in the German sex industry, very few have been able to access this aid due to the repressive registration criteria that was introduced in 2017 and their exclusion as migrants from legal forms of sex work. The majority of EU migrants managed to return to their country of national citizenship, including Bulgaria, Romania, Poland and Ukraine, but those who could not have faced destitution and homelessness.

Surveillance and policing

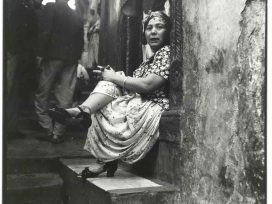

Police tasked with enforcing new public health regulations since late February have become more present on Europe’s streets. While mainstream feminist groups often advocate police intervention as a solution to violence against women, sex worker communities, especially undocumented migrants and women of colour, have long been speaking out against police surveillance and violence targeting trans women, women from low socio-economic backgrounds and migrants. Reports suggest that sex workers are targeted by police and immigration authorities both at and beyond their places of work. For example, Roma sex workers from Central-Eastern Europe frequently provide accounts of being checked by police even when they are not working. And Chinese sex workers often even fear going out for groceries in Paris due to regular identity and immigration status checks.

Increased police surveillance in a number of countries has led to sex workers being escorted home from their street workplaces during the lockdown. The authorities have also been accessing online adverts and calling sex workers to tell them to stop working, triggering distress within the community, especially for undocumented migrants. Although the criminal justice system ostensibly shut down in mid-March, raids, arrests and prosecutions have reportedly continued in the UK, amongst other countries. The situation was especially dire in southern Italy: in Naples, street workers, who are mainly women of Italian nationality, resumed work as they had no other option and faced €400 fines and physical abuse from police officials, who called them ‘vectors of disease’. Undocumented migrants were not deported, as borders remained closed, but many received expulsion orders during the lockdown.

And scapegoating is not reserved to the police – the media also participate. Sex worker rights groups reported a spike in media interest at the beginning of lockdowns, with numerous inquiries about the behaviour of clients and sex workers moving online and engaging in cam work. While sensationalist features were published with detailed descriptions of sexual acts performed in protective gear, little attention was paid to the fact that sex workers do not get the kind of state support regular workers receive and, therefore, have been providing one another with mutual aid.

Community support

During the first two months of the crisis, no European government explicitly mentioned sex workers as a vulnerable group in need of protection in their emergency responses to the crisis. This did not surprise and the community had to rely on their own very limited resources to address wide reaching destitution. In the absence of government support, self-help online initiatives and fundraisers were quickly launched all across Europe, which provided some financial help and peer mental health support to those in most need.

These independent programmes have faced backlashes from abolitionist activists and governments, who have intensified their advocacy of the Swedish model’s introduction, which criminalizes sex workers’s clients. Some abolitionist organisations in Spain even celebrated the ‘Abolovirus’ for providing women with an ‘opportunity’ to turn away from prostitution and start a new life. Meanwhile, the French government advocated a programme to help workers ‘exit prostitution’ despite its offices that administrate the scheme being closed. This highly bureaucratic process offers a monthly €330 allowance intended to cover lost income, which is far below the basic solidarity income. From an estimated 40,000 sex workers, less than 300 women have accessed this programme since France criminalized sex workers’s clients in 2016. In contrast, the French sex worker union, Syndicat du Travail Sexuel (STRASS) supported more than a thousand beneficiaries with immediate and unconditional financial donations over the past two months.

In Scotland, a £60,000 fund set up by the government’s Immediate Priorities Fund addresses the needs of sex workers but comes at a cost. The associated Encompass Network, which includes nine organisations involved in sex worker support, defines prostitution as violence against women and campaigns for client criminalization. Umbrella Lane, a sex worker-led group, was meanwhile excluded from the scheme. Although the group ran a campaign to raise £20,000 in emergency funds for the hardest hit workers during Scotland’s lockdown, the volunteer-run intervention did not seem to merit the group’s state support.

Despite all these obstacles, sex workers are using the crisis to shape a new agenda for equality. While all self advocacy groups demand decriminalization in the long run, more nuanced discussions are now emerging on how to address the root causes of why so many women, LGBT people and migrants enter this highly stigmatized and criminalized industry. In recent months, sex workers from various European countries not only helped their communities on the ground but also regularly came together online to formulate their list of demands.

More than a hundred organizations have endorsed a manifesto that demands governments implement comprehensive social policies for the most vulnerable and for society at large. Signatories demand that undocumented migrants, including those in the sex industry, receive the chance to legalize their status, and have access to health and social services, legal housing and justice without the threat of being arrested and deported or otherwise criminalized.

They also emphasize much needed economic reforms, including basic care and universal income, and an end to racial and gender profiling practices and repressive immigration policies.

What feminists can learn from sex workers

COVID-19 is not only a public health challenge but also a test of feminist solidarity. Sex workers and their small collectives – often operating on shoestring budgets or entirely without funds – have built on grassroots activism during the crisis, which challenges the image of sex workers as passive victims. In addition to distributing essential funding to members, they have also organized online mental health counselling sessions, helped challenge exploitative landlords, tackled police harassment and drafted guidelines to help victims of domestic violence without involving the police. These experiences of solidarity serve as inspiration to feminist activists, producing knowledge about issues that are not on the mainstream feminist agenda: the situation of migrant women and women of colour; increasing female poverty and precarization of work in neoliberal economies; and the role of policing and state-driven violence.

Judging from the experiences of the 2008 financial crisis and the following austerity policies, sex workers expect many more women, migrants and LGBTIQ people to enter the sex industry once lockdowns are lifted, having accumulated debts after losing their jobs. Listening to sex workers and proactively supporting their demands could save these people the experiences of precarity, exploitation and state criminalization.

Published 3 June 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Boglárka Fedorkó / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

‘Sex work will disappear the day we abolish capitalism. Until then, let’s talk about labour rights.’ Amaranta Heredia Jaén calls to address the controversial results of anti-trafficking measures.

Prisoners of conscience

A conversation with Myroslav Marynovych

Defenders of human rights often face high stakes. When the Ukrainian Helsinki Group openly challenged the Soviet Union in the name of the 1975 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, young dissidents soon became political prisoners. The price for being a non-conformist was steep yet encouraged solidarity, paving the way to Euromaidan.