‘Justice’ has recently become the explicit goal of many global citizen movements. In contrast to domestic justice advocates, transnational justice theorists and activists argue for broad, in-depth commitment that reaches beyond the wellbeing of their immediate communities and fellow citizens to encompass strangers both within and beyond state borders. They suggest that social duties and responsibilities should not be limited to fellow citizens in a globalized world. A concurrent effort emphasizes the economic, political, cultural and sexual aspects of injustice.

Powerful actors, organizations and nation states are increasingly expected to be ethically responsible for vulnerable sectors of the world population within the growing context of global interdependence. At first glance, the demand on transnational elites to act beyond a narrow, territorial-based understanding of self-interest to ‘protect’ victims of injustice seems convincing. However, given the West’s long and violent history of colonial intervention, current attempts to act on behalf of distant others often invoke suspicion and distrust. Euro-American supremacism and paternalism are reinstated as dispensers of rights and justice.

In Cultivating Humanity, the American philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes, ‘The world around us is inescapably international. Issues from business to agriculture, from human rights to the relief of famine call our imaginations to venture beyond narrow group loyalties and to consider the reality of distant lives. [. . .] Cultivating our humanity in a complex, interlocking world involves understanding the ways in which common needs and aims are differently realized in different circumstances.’ From a contemporary feminist perspective, gender justice involves an intersectional and transnational focus and a turn away from previous articulations of ‘global sisterhood’.

March 8 rally in Dhaka, organized by Jatiyo Nari Shramik Trade Union Kendra (National Women Workers Trade Union Centre), an organization to the Bangladesh Trade Union Kendra. Photo by Soman from Wikimedia Commons

At first, the demand on citizens of liberal democracies to take responsibility seems reasonable. Cosmopolitanism, also based on the normative espousal of an expansive global consciousness, opposes such narrow and limited territorial loyalties. Transnational citizen movements envisage democratic global institutions that could facilitate direct participation in global politics and counteract the financialization of the global economy. The German sociologist Ulrich Beck considers that increasingly interdependent living presents common threats to ecologies, finances and security, whereby any violation of rights in one part of the world is felt everywhere. This ‘globalization of risk’ unites society in its equal vulnerability and establishes a ‘cosmopolitan moment’. In response to the question ‘How can the relationship between global risk and the creation of a global public be understood?’, Beck discusses the ‘globalization of compassion’. One recent example would be the Haitian earthquake and tsunamis witnessed as global media events, which spectacularly demonstrated the unprecedented willingness of citizens in faraway countries to donate to relief efforts. The extreme threats to a world risk society open up questions of social accountability and responsibility that cannot be adequately addressed by national politics or current international cooperation. International civil society protagonists, indispensable to cosmopolitan values and their implementation, could initiate a more just, alternative globalization.

Nussbaum and Beck may enthusiastically endorse cosmopolitanism as a ‘solution’ for past injustices and a ‘promise’ of better times to come, but I would like to emphasize the complicity between liberal cosmopolitan solidarity and the global domination structures it claims to resist. Liberal cosmopolitanism’s detractors consider that global capital is the inevitable precondition for a contemporary cosmopolitan sensibility. They argue that cosmopolitanism leaves the global elite’s privileges intact by erasing the continuities between cosmopolitanism, neocolonialism and economic globalization. Postcolonial feminists, in particular, reveal how transnational alliances can be mobilized to service predatory global capitalism and imperialism.

I object to the cosmopolitanism project. It fails to seriously address the historical processes through which certain individuals are well-positioned to express their aspirations for global solidarity and universal benevolence. Nussbaum, to her credit, explores how people’s lives could be improved. But that in itself is a problem. Her attempt to act in the interests of distant others, to look beyond her position and give everyone as good a life as ‘ours’, disregards the connection between the well-off ‘here’ and the impoverished ‘elsewhere’.

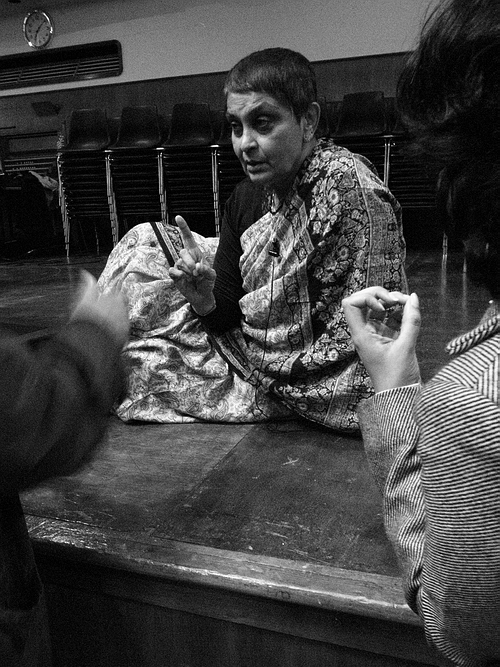

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak at Goldsmiths College, University of London, 2007. Photo by Shih-Lun CHANG from Wikimedia Commons

In contrast to Nussbaum’s faith in cosmopolitanism’s self-correctional reflexivity, the postcolonial feminist Gayatri Spivak diagnoses the cosmopolitan call as a means to shift the perception of fellow citizens from ‘the white man’s burden’ to ‘the burden of the fittest’. This revision of social Darwinism defines the ‘unfit’ as unable to help or govern themselves. The distance between those who ‘dispense’ justice, aid, rights and solidarity, and those who are simply coded as ‘victims of wrongs’, and, thus, as ‘receivers’, remains a signature of historical violence.

Conversely, Beck proposes that common vulnerability to risk brings us together. But, as we all know, though we may face the same storm, we are not all in the same boat, and this makes all the difference. For Beck, the tsunamis resulted in the ‘globalization of compassion’. As an instructive contrast, I would like to consider a moment in Spivak’s narrative that describes a major cyclone in Bangladesh in 1991 and the subsequent intervention by Médecins sans frontières. The international humanitarian medical NGO’s workers were obliged to work through interpreters as none of them spoke the local language. When Spivak arrived at one of the villages where she had actively worked in the past, some of the villagers ran up to her saying, ‘We don’t want to be saved, we want to die, they are treating us like animals.’ In a situation like this, without a common language, are we even able to think of solidarity?

The postcolonial scholar Robert Young describes the dilemma that benevolent Europeans face as follows, ‘If you participate you are, as it were, an Orientalist, but of course if you don’t, then you’re a eurocentrist ignoring the problem.’ Spivak counters, ‘It’s not just that if you participate you are an Orientalist. If you participate in a certain kind of way you are an Orientalist and it doesn’t matter whether you are white or black.’ She goes on to say that doing one’s homework and progressing beyond a merely superficial interest in the Third World is commendable. But ‘[y]ou can’t just be a revolutionary tourist and be the Saviour of the world on your off days.’ This sounds very harsh but warns against romantic notions of unreflected solidarity.

With similar concerns in mind, the Sri Lankan feminist Malathi de Alwis has asked if we are truly capable of empathizing with the pain of others and if we should even be allowed to witness this pain when witnessing only serves to affirm our humanity and capacity to care. Correspondingly, we may effectively be searching for ‘authentic victims’ who truly deserve our benevolence. So what should we do with our ‘will to empower’ the ‘disenfranchised and the vulnerable’ and how can we approach those who refuse to be identified as objects of our solidarity?

“There Is No Coming Back” – Women’s Day March in Istanbul

Photo by Özge Sebzeci / Conflict & Development at Texas A&M from Flickr

Erotics of resistance

In recent decades, a proliferation of protest movements has sought to reconfigure international politics by interpellating the global demos that have been wronged by the neoliberal beast. From Puerta del Sol to Taksim, from Syntagma to Tahrir Square, from Hong Kong to New Delhi, street politics seem to have transformed the way power, agency and resistance are being perceived and performed. Counterpublic spheres, where new actors appear on the political stage by appropriating and re-signifying political discourses, are arguably questioning issues of redistribution, recognition and representation. In replacing the Habermasian public sphere, where rational subjects come together to deliberate over common interests, counterpublics can reshape state-society relations through public anger, outrage and frustration. Counterpublic spheres manifest multiple emancipatory ways that challenge and transform the dominant forms of rule in economic, cultural and socio-political arenas. The San Precario movement, the Arabellions, the Indignados movement, the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations and various refugee strikes against coercive migration regimes are all examples of countermovements and counterpublic spheres that have emerged to counter neoliberalism and neocolonialism’s intersecting power dynamics. Despite important differences between the goals and strategies of these protest movements, they are all horizontally organized and largely network via social media. Direct street action allegedly brings together heterogeneous groups, inducing ‘spontaneous solidarity’. When opposing their disenfranchisement and marginalization, and demanding political accountability, these bodies on the street are vulnerable to police brutality and state violence. The corporeality and collectivity of the masses exercise the popular will, a bodily message of popular sovereignty. Occupying and claiming public spaces shifts political life from corridors of power to the street. Dispossessed bodies evidence their subversive and disruptive potential, reclaiming democracy from capitalism and corporate power. Public protests – whether asylum seeker hunger strikes in Berlin or a fruit vendor’s self-immolation in Tunisia – are symbols of global resistance.

Concepts such as ‘precarity’, ‘bare life’, ‘wasted lives’, ‘disposable lives’, ‘the superfluous’, ‘the outcasts’ are mobilized to describe marginal political subjectivities and decentered practices of political agency. Despite significantly different approaches, all of these concepts engage with disenfranchisement and dispossession. They outline how the governmentality of efficiency, profitability, accumulation, optimization and instrumentalization renders most populations expendable and disposable through exploitation and militarization.

Protest movements around the world contest these developments and promise radical political change by shaming powerful states and international financial institutions into good behaviour. However, one question remains: How effective are ‘Facebook revolutions’ and ‘Twitter insurgencies’ in transforming the social, political and economic relations of late postcolonial capitalism? In my view, an intrinsic ambivalence exists at the heart of these protest movements. On the one hand, resistance cannot be envisioned without the longing, desire, ideas and fantasies for another political order; these movements powerfully negate the ‘There is no alternative’ (TINA) principle. On the other hand, these aspirations wittingly and unwittingly reproduce the subalternization of marginal subjects and collectives that have a tenuous relation to both the state and global civil society, including counterpublic spheres. The movements’ romantic enthusiasm erases exploitative and exclusionary material conditions, allowing dissidents to exercise their agency. However, when an anti-capitalist protester tweets from their iPad produced under super-exploitative working conditions in the global South, capitalism’s subversion is revealed as a phantasma, a surreal moment of class-privileged jouissance. Such enjoyment reflects the erotics of resistance marked by a new international division of labour, which sustains the discontinuities between those who resist and those who cannot.

The 2017 Pro-jallikattu protests in Marina Beach, Chennai, India

Photo by Gan13166 from Wikimedia Commons

Despite the powerful images that ‘bare life’ or ‘disposable lives’ protesters mobilize to mirror their vulnerability, many of these concepts reproduce Eurocentrism. For instance, the recent focus on precarity, closely related to the welfare state’s disintegration in different European countries, conveniently disregards that poor or non-existent health care is the norm beyond the Western world. The majority of the global South’s population has never had access to the formal labour market, health insurance or unemployment benefits, and has been living with the insecurity and anxiety caused by causal employment for decades. The irony now is that the scene of the crime has expanded. What the Western world imposed in the name of structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) abroad is now being implemented in the global North.

Enthusiastic discourses about resistance and fantasies of hyper-agency also tend to overestimate the scope and influence of these political initiatives. Tweeting one’s way out of capitalism is a self-evidently absurd claim. In Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari elaborate the erotics of capitalism: ‘[…] the way a bureaucrat fondles his records, a judge administers justice, a businessman causes money to circulate; the way the bourgeoisie fucks the proletariat; and so on. […] Flags, nations, armies, banks get a lot of people aroused’. I would add that fantasies of radical change through protest politics are getting a lot of young, urban, class-privileged people very aroused. The spectacle of resistance as jouissance empowers protesters. They think it is their duty to save the planet and demonstrate solidarity with marginalized groups, veiling the fact that they are complicit in the very structures they are contesting. Only a limited group fulfil the criterion of citizenship invoked by the normative concept of civil society, thus disenfranchised groups can only unevenly access organized political arenas. Spaces of resistance themselves produce exclusions that complicate a straightforward understanding of power, agency and vulnerability.

It may be that no social movement can ever be all-inclusive. However, if one understands the ‘subaltern’ not in terms of identity but relationality – namely, that something always escapes every emancipatory political initiative – this would guard against the enthusiastic celebration of radical change through street politics, digital publics and protest movements. I strongly suggest a critical reworking of how resistance is understood to counteract seductive terminology such as ‘tweeting the revolution’, which inadvertently stabilizes the hierarchical relationship between hegemonic and subordinated groups. In response to Foucault’s claim ‘where there is power, there is resistance’, I would add ‘where there is resistance, there is power’.

Complex transnational feminist solidarity issues have gained specific urgency in relation to the Syrian refugee crisis. Homelessness and exile have brought notions of hospitality and cosmopolitanism as enlightenment norms to the forefront of our attention once more. The scope and scale of responsibility related to the suffering of others is central. In his discussion of cosmopolitan ethics (Weltbürgerrecht), Kant addresses the rights and duties of those who wish to cross borders. He argues that all world citizens should have the right to free movement based on humankind’s common ownership of the earth. Kant proposes cosmopolitanism as a guiding doctrine that should protect people from war. His notion of cosmopolitan right morally embeds the principle of universal hospitality, encompassing both the stranger’s rights and the host’s duties and obligations. However, it is difficult to imagine any right that has been more violated than the right to mobility in the current age. Migrants are the bearer of Kant’s message as they struggle to move across borders, while the humanitarian disaster unfolding on Europe’s doorstep signals yet another betrayal of enlightenment principles.

When the refugee crisis worsened, Germany suspended the Dublin regulation and opened its borders. However, its ‘welcoming culture’ was short-lived. The sexual assaults perpetrated by some migrant men during the 2015 New Year’s Eve celebrations in Cologne were a turning point, which reduced Germany’s previous consensus to accept large numbers of refugees. Some German feminists protested against recycled racial stereotypes of misogynistic Islamic culture, victimized Muslim women and aggressive Arab masculinity. But many more Germans supported the deportation of miscreant male refugees and encouraged mandatory ‘respect for women’ courses for Muslim men, concealing racism under the cloak of feminism. Unfortunately, increasing sexist, racist and xenophobic violence against migrant and refugee women has not received the same degree of critical attention. Some bodies are coded as needing to be protected and others as those to be protected from. The privilege that one’s body could be understood as vulnerable is granted to few despite being a right for all. Anti-racist, post and decolonial practices seem to fall on deaf ears in these excitable times, which are defined by security and securitization. Muslim immigrants are perceived as a threat to liberal values such as gender equality that Europeans cherish. Gendered vulnerability, mobilized as a legitimizing narrative, frames non-Western people and cultures as misogynistic and violent. European society is simultaneously freed from the suspicion of sexist and heterosexist behaviour. Both aspects present an enormous challenge to feminist ethics regarding transnational solidarity issues. They raise the questions of how to address gendered vulnerability without reinforcing orientalist stereotypes, and how to exercise solidarity without either trivializing violence or patronizing victims. These ethical dilemmas on gender violence serve as example of how fickle proclamations of transnational solidarity can be.

Against the claim that our common vulnerability brings us together, I would counter that deep asymmetries of power and wealth cannot be corrected through transnational solidarity alone. Both civil society and social movements are marked by hierarchies and exclusions that are disturbingly overlooked in celebratory discourses about their opposition to the state. Vicious neocolonial and imperialistic consequences can stem from the state positioned as an agent of terror and civil society as an agent of salvation, especially for subaltern groups. Transnational counterpublics tend to empower transnational civil society actors, whose ‘will-to-do-good’ and ‘will-to-resist’ is marked by feudality and enabled by neoliberal framing. It is therefore imperative to ask whether enthusiastic discourses of resistance empower disenfranchised communities or simply reinforce the domination between those who act and those for whom these colourful and lively uprisings and revolts are being staged.

Desubalternization, the process of deconstructing the coded inequality of certain groups within a discourse, is unbearably slow, while revolution fantasies via Twitter and Facebook move at the speed of thought. For Marx, as Spivak reminds us, capital moves with Gedankenschnelle. In What Is to Be Done?, Spivak revisits Lenin’s suggestion, recommending that international civil society’s vanguardism should be supplanted by the slow, patient work that enables subaltern access to hegemony. Rather than solely teaching subalterns how to resist through political indoctrination or consciousness-raising, the advice focuses on the privileged classes unlearning the impulse to monopolize agency in the name of saving the world ‘here-and-now’ and subalterns unlearning the underclass-related habit of obedience.

Desubalternization’s shift from street politics to other arenas of intervention would be necessary; as with the postcolonial state, desubalternization is like a pharmakon – both poison and remedy. In contrast to the state-phobic rhetoric of protest movements, I envisage the exploration of strategies that could reconfigure the relationship between the postcolonial state and the subaltern, thereby converting poison into counterpoison.

Those on the privileged side of transnationality have to resist becoming self-selected moral entrepreneurs in charge of finding solutions for the world’s problems. Caught in a double bind, international civil society actors must learn to acknowledge that they intimately inhabit the very structures that they seek to critique. ‘The voice of the people’, as an act of political speech that authentically expresses the popular will, reveals itself as a phantasma – protest movements ironically subalternize the masses at the very moment when they seemingly allow them to speak. The complicit, ongoing reproduction of subalternity complicates alliances formed along class, race and gender lines, and raises troubling questions regarding postimperial feminist politics in the era of neoliberal globalization.