An example of decency

What the life of the Sheptytsky brothers means for contemporary Ukraine

Andrei and Klymentiy Sheptytsky, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic clerics who resisted both Nazi and Soviet oppression, have played an important role in shaping Ukrainian political identity. Polish intellectual and diplomat Adam Daniel Rotfeld was one of the many children of Jewish descent sheltered in the Sheptytskys’ monastery during WWII. Here, he re-evaluates the biographies of the two brothers.

The Sheptytsky brothers played an important role in shaping the communal political identity of Ukrainians. Adam Daniel Rotfeld’s research led him to conclude that the Sheptytsky brothers also played a pioneering role in the promotion of ecumenism. But there has also been some ambivalence in evaluations of Metropolitan Andrei’s activities. The Yad Vashem institute in Jerusalem declined to grant the Metropolitan the title of Righteous Among the Nations, although his brother, Father Klymentiy, was honoured this way. How should the Sheptytsky brothers’ activity and service be judged from today’s perspective? And how should historical memory be shaped, given the complicated nature of Polish-Ukrainian relations?

Piotr Kubasiak

The formation of Ukrainian identity in Eastern Galicia

During and after World War II, the Sheptytsky brothers played an extraordinarily important role in Ukraine. The life of Andrei Sheptytsky, Metropolitan of the Greek Catholic Church in Lviv, has long been a topic of interest for scholars. He has been the subject of many monographs and anthologies, several of which are of a very high standard. While it would be difficult to add anything new here, it is not impossible. It would, however, demand extensive archival research. After all, Andrei Sheptytsky was not only a great cleric and spiritual teacher – he was also, in fact, fundamentally one of the founding fathers of the modern Ukrainian nation.

The history of the Sheptytsky family is a unique lens through which to view the Habsburg notion of multiculturalism. The Sheptytskys were aristocrats in the best sense of the word – not only by birth, but also by spirit. The Sheptytsky brothers’ parents came from noble families. Their mother, Zofia, was the daughter of the famous Polish playwright, Count Aleksander Fredro, and their father, Jan Kanty Szeptycki, came from a family whose genealogy could be traced back to the beginning of the thirteenth century, from the time of the Kingdom of Halych. The first mentions of the Sheptytsky family date from the period when Galician Rus’ was ruled by Danylo, the only crowned King on the territory of modern-day Ukraine. It was King Danylo who built a city for his son Lew (Leo), which bore the Latin name Leopolis – in Polish Lwów, in Ukrainian Lviv, and under Austrian rule the capital of Eastern Galicia was given the German name Lemberg.

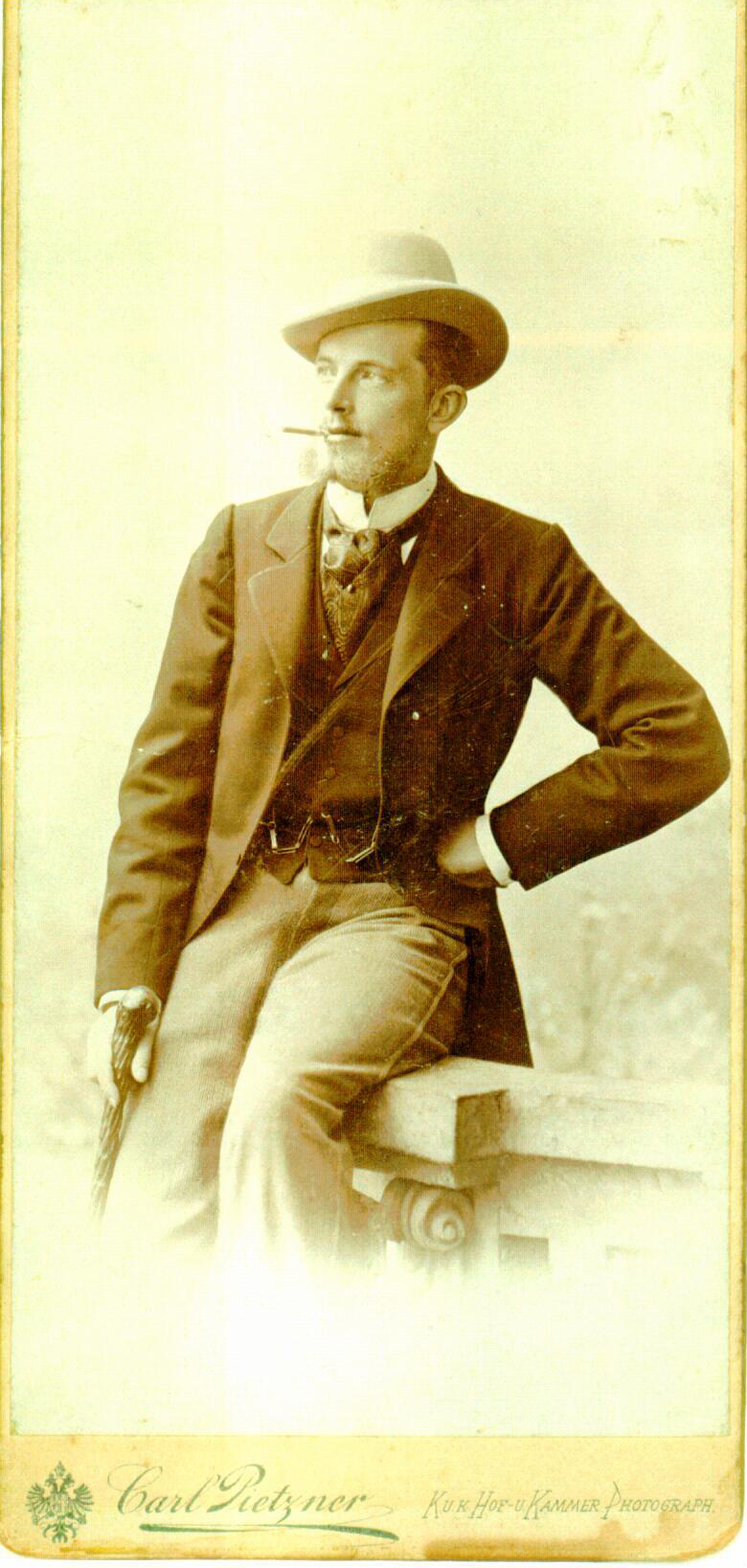

Zofia and Jan Kanty had seven sons, two of whom died in childhood. Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, who was christened Roman, took the monastic name Andrei when he joined the Basilian monastic order. His younger brother Kazimierz, after completing his studies, began an impressive political career in Vienna. He was not only a member of the Austrian parliament – first the lower house, then the upper house (Herrenhaus) – but also a member of the State Council convened by the Kaiser. When he was in his forties, he entered a monastery and took the name Klymentiy.

Klymentiy Sheptytsky, still known as Kazimierz, as a young politician in Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century.

Andrei’s third brother, Stanisław, made a military career for himself in Austria, and, after Poland gained independence, became a general in the Polish Armed Forces. Finally, there came Aleksander and Leon. Both were landowners, living together with their sizeable families in Łaszczów and Łabunie (Aleksander) and Przyłbice (Leon) in houses that were, both at the turn of the century and later, up until 1939, family ‘nests’ of a sort. That was where everyone gathered for festivities and spent their holidays.

A meeting of the Sheptytsky brothers before World War II at the family estate in Przyłbice.

Seated: Metropolitan Andrei. Standing from left: Klymentiy, Stanisław, Aleksander, Leon.

Roman and Kazimierz attended the oldest and best school in Cracow (Kraków), the St Anna Gymnasium (now the Nowodworski Lycée), and then studied law at Jagiellonian University. They also studied in Breslau (now Wrocław), Vienna, Munich, Paris, and other cities. From their earliest years, they put great emphasis on their spiritual and intellectual development. They belonged to the Polish elite in every way – their aristocratic affinities, their material wealth, their sound education at home, and the high level of knowledge they gained at the best European universities.

Their decision to become monks, especially in the Greek Catholic Church, was not welcomed by their family. On the contrary, they were met with a lack of understanding and resistance, especially on the part of their father, who could not accept the fact that his sons had decided not only to enter monastic life, but to bind themselves to the Ruthenians – the simple folk, the Galician peasantry.

Andrei and Klymentiy rewrote the monastic rule of the Studites, who split off from the Basilian order in the first decade of the twentieth century. The order had been abolished by the Austrian authorities in the eighteenth century, after the Partitions of Poland. The order’s monasteries were meant to – and with time did – serve as centres for promulgating education, spiritual, and material culture: that is, means of cultivating the land that were essentially autarchic (with their own workshops and machinery, harvester, mill, and tannery; their own production of canvas, oil, and juices; and beekeeping).

The brothers’ parents were aware that their sons were choosing a path that would inevitably lead to their alienation. Among the Polish elite they became known as traitors to the ‘Polish cause’, and they also were not welcomed by the Ukrainian peasantry, partly because of their high status and their aristocratic origins, but also simply because they were Roman Catholic Poles. In spite of everyone and everything, they decided to convert to the Greek Catholic rite. They learned Ukrainian as adults, although they never got rid of their strong Polish accents and until their dying days continued to use Polish words in conversation (a fact that was carefully noted by the Soviet Special Service – NKVD officer who reported on his conversation with Archimandrite Klymentiy shortly before the latter’s arrest).

The Sheptytskys learned Ukrainian as adults not only because they felt called to it, but also so that they could interact with the faithful and the Ukrainian clergy. Despite their persistent Polish accents, they indeed became authentic spiritual leaders of the Ruthenians. At the turn of the twentieth century, the term ‘Ruthenian’ – not Ukrainian – was more popular. The Sheptytskys became driving forces behind the emerging identity of the Ukrainian community in Eastern Galicia. They enjoyed indisputable authority and respect from the political elite of Ukraine (Ukrainian as well as Polish and Jewish) and even from the occupiers – first Soviet, then German. Although, some radical fascist Ukrainian nationalists treated them as foreigners sent from Poland or Rome to pursue the Vatican’s interests. This hostility was mainly directed at the Metropolitan, since his brother was not a public figure.

This does not mean that Andrei Sheptytsky never made mistakes. The critical assessments offered by scholars today, however, are often completely detached from the realities of the time.

Andrei and Klymentiy Sheptytsky and the Holocaust

In the interwar period, Andrei Sheptytsky developed a good relationship with the Jewish community. During holiday gatherings he addressed the gathered crowd in Hebrew.1 He was in contact with various sorts of people in the Jewish community including lawyers and economists, but also – and perhaps above all – rabbis. I am thinking particularly of his relationships with Jecheskiel Lewin, rabbi of the Reform synagogue in Lviv from 1928, and Kalman Chameides, Chief Rabbi of Katowice who ended up in Lviv in 1939 after the German invasion of Poland and the incorporation of Eastern Galicia into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The sons of both of these rabbis were protected in Studite monasteries thanks to the personal efforts of the Sheptytsky brothers. They attested to this in published memoirs, which are of great documentary value. Their publications are a tribute and expression of gratitude to Andrei and Klymentiy Sheptytsky. Particularly noteworthy are two publications – the first by Kurt I. Lewin, the second by Leon Chameides.2 The eminent Polish haematologist, Professor Aleksander Skotnicki gave me a recording of an interview conducted with Lili Pohlmann in her London flat twenty years ago. During the war, she was hidden together with her mother and three others – the pharmacist Podoshin, his wife, and their young daughter – in Lviv by the German civil servant Imgarda Wieth. Before the war, Podoshin supplied medication to the Metropolitan and came into contact with the people in his circles. As Lili Pohlman tells it, ‘The Metropolitan of that church, Archbishop Count Andrei Sheptytsky, received us in his palace seated in a wheelchair’. He hugged Lili, stroked her head and said, ‘Do not be afraid, child, nothing bad will happen to you.’

The mother and daughter made it to the convent on Uboch street, past the Lychakiv checkpoints. Leszek Allerhand, a medical doctor from Zakopane and the son of the famous legal scholar and professor at the University of Jan Kazimierz in Lviv, Maurycy Allerhand, wrote a book dedicated to his father. I would like to cite one passage of the volume: ‘When German troops arrived in Lviv, the city was home to around 165 thousand Jews.’ Elsewhere, the author notes dryly that, ‘874 Jews survived in Lviv, including four married couples with children. One of these families was my parents and me.’3 These statistics give a more accurate picture of what happened in Lviv from June 1941 to June 1944 than any other description, analysis, or assessment. At this time, the Sheptytskys were actively engaged in saving Jews. Everyone living in occupied eastern Galicia was persecuted – not only Jews, but also Poles and Ukrainians. The difference was, as Polish politician and intellectual Władysław Bartoszewski put it, that ‘any Pole could die, but every Jew had to die’.

The Sheptytsky brothers risked their own lives to help. One of the people saved by them was David Kahane, who later became chief rabbi of the Israeli Air Force and then chief rabbi of Argentina. During the war, dressed as a Studite monk, he worked under the name Brother Mathew in the Metropolitan’s library. In addition to the librarian’s daily responsibilities, Sheptytsky entrusted him with the translation of Psalms and other Bible passages from Hebrew or Aramaic into Ukrainian, because the version of the Bible that existed then was a translation from the Vulgate into Old Church Slavonic. In a way, Sheptytsky’s initiative was a forerunner to the decisions made by the Holy See after the Second Vatican Council. In the Greek Catholic Church – like in the Orthodox Church – both the liturgy and the Holy Bible were already available in Old Church Slavonic – a language that the faithful could understand. However, there were different ways of understanding the message of the Holy Bible…

For centuries, Eastern Rite Churches used a translation in a language that today few people understand. I had my own experience of this. As a boy, during the war I ended up in the Studite monastery in Unev, near Peremyshlany (Polish name – Przemyślany). At the time, Klymentiy Sheptytsky was the abbot – later he would become the archimandrite of the entire order. I was not yet four years old at the time. By nature I grew up quickly, but I still could not go to school. My caretaker, Brother Danyil, decided that every day I should learn five words in Old Church Slavonic. With time I realized that this helped me first to read Ukrainian and Russian fluently, and then to speak them – without a Polish accent.

Children in the monastery with Brother Danyil (Tymchyn, who was granted the title of Righteous among the nations by Yad Vashem). Adam Daniel Rotfeld is in the second row, third from the right.

Metropolitan Andrei’s relationship to Orthodoxy

On the basis of unpublished letters and other documents, as well as the memoirs of their mother, Zofia Szeptycka (née Fredro), I believe that the main motivation for both brothers was an ardent faith and a sense of mission. Both Andrei and Klymentiy made their decision independently – contrary to the expectations of their milieu, under no influence, and without political inspiration. They were conscious of the resistance and difficulties that they would encounter, as well as of the fact that they would become ‘strangers among their own’.

Klymentiy Sheptytsky grew up in Andrei’s shadow, where he remained for many years. In 1911, at the age of 42 and at the height of his political career, he decided to enter a monastery. The spiritual, organizational, and material efforts of both brothers gave rise to a network of convents that belonged to the Studite order, which – alongside the Basilians – became the most influential sites of the formation of Galician Ruthenian spirituality. The most important of these monasteries was unquestionably the one in Unev. It was among the oldest monastic communities in western Ukraine, whose beginnings date back to the twelfth century. After 1596, it was the main Uniate centre on Ruthenian-Galician territory. In the eighteenth century, the Basilian order took over the monastery’s buildings, until that order was abolished by the Austrians (after the first partition of Poland).

In 1919, Andrei Sheptytsky turned the monastery over to the Studites and appointed his brother Klymentiy ihumen (abbot). I think that the brothers’ main goal in life was not only educating the Ruthenian population, but also beginning the process of restoring Christian unity between Catholics and Orthodox Churches in Ukraine. The brothers’ role and significance in this regard are underestimated. They believed that the Greek Catholic Church could not be treated like a thorn insidiously driven into the side of Orthodoxy by the Vatican and were convinced that their Church could play the role of mediator. In this respect, their thinking was ahead of its time.

Archbishop Andrei Sheptytsky was respectful of Orthodoxy and pursued a theological dialogue with the hierarchs of the Orthodox Church. Later, under radically different political circumstances when the Red Army returned to Eastern Galicia (1944), Klymentiy – following Andrei’s death – sought to find a modus vivendi that would permit the preservation of the Greek Catholic Church and its autonomy in a sort of coexistence with Orthodoxy, which dominated in Russia and Ukraine. But the Soviet authorities had a different goal; as a matter of principle they did not accept the Greek Catholic Church. This was not only because it was subjugated to the Pope, but also because it was connected with – and spiritually supported by – the underground Ukrainian independence movement. After Andrei Sheptytsky’s death in November 1944, the special Soviet secret services were tasked with eliminating the Union of Brest (1596) and subordinating the Greek Catholic Church to the Russian Orthodox Church. The new Metropolitan Iosyf Slipyi, Klymentiy Sheptytsky and many other Greek Catholic bishops refused to collaborate in these plans. As a result, many clerics were arrested. In 1946, the Soviet authorities formally prohibited the Greek Catholic Church and its churches and other property were transferred to the Russian Orthodox Church.

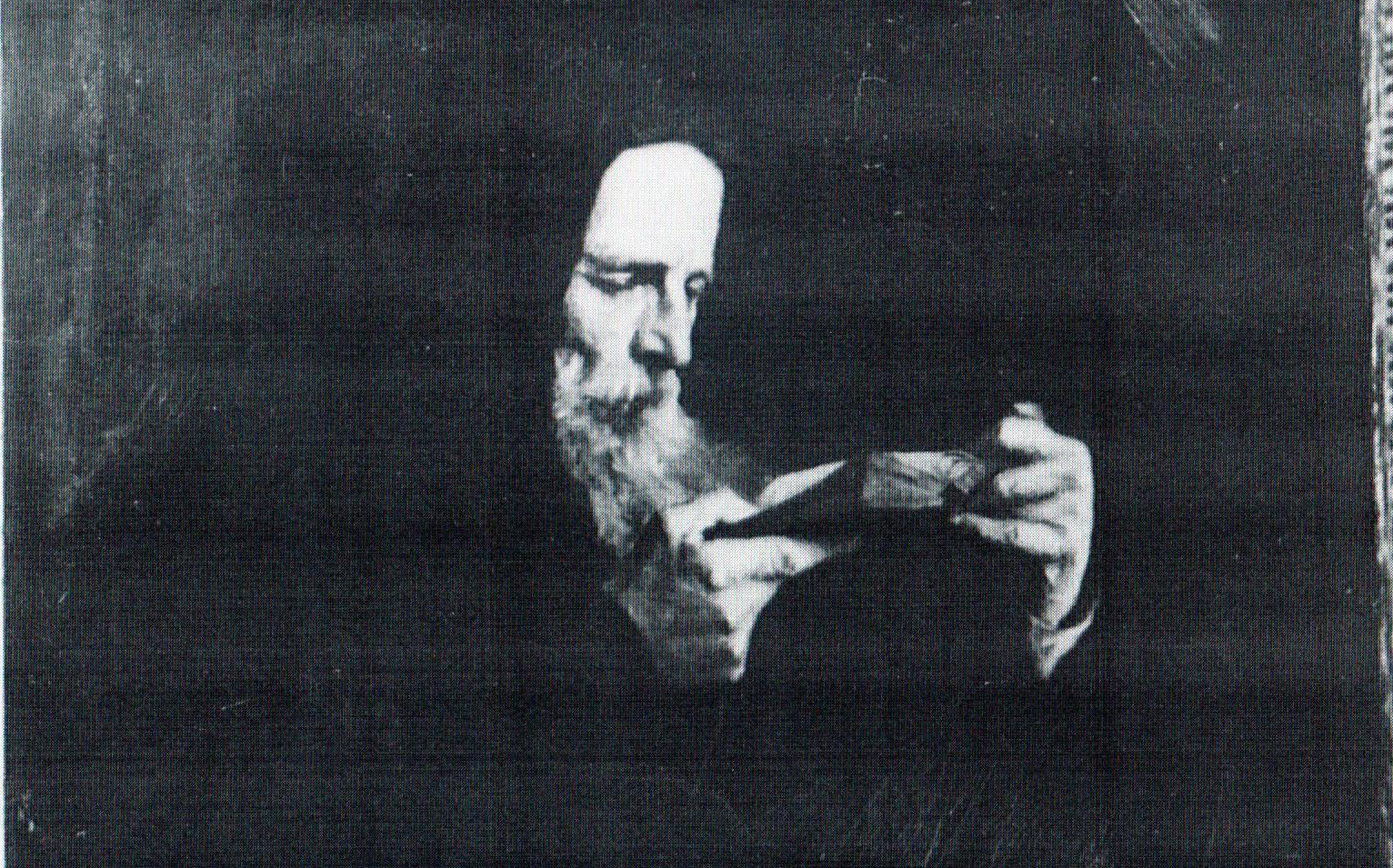

Ihumen of the Unev Monastery, Father Klymentiy, in the monastery shortly before his arrest.

It was only in the very last days of the Soviet Union, following a visit by the Secretary General of the Soviet Communist Party, Mikhail Gorbachev, to the Vatican in December 1989, that the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was officially restored. This step was all the more justified because the Church had continued to exist underground for all those years – since the end of WWII. The role played by Klymentiy Sheptytsky in the Church’s history was recognized through his beatification by John Paul II, which was announced during the pontiff’s memorable pilgrimage to Ukraine in 2001. This was the capstone of the long and difficult path that the Sheptytsky brothers had chosen.

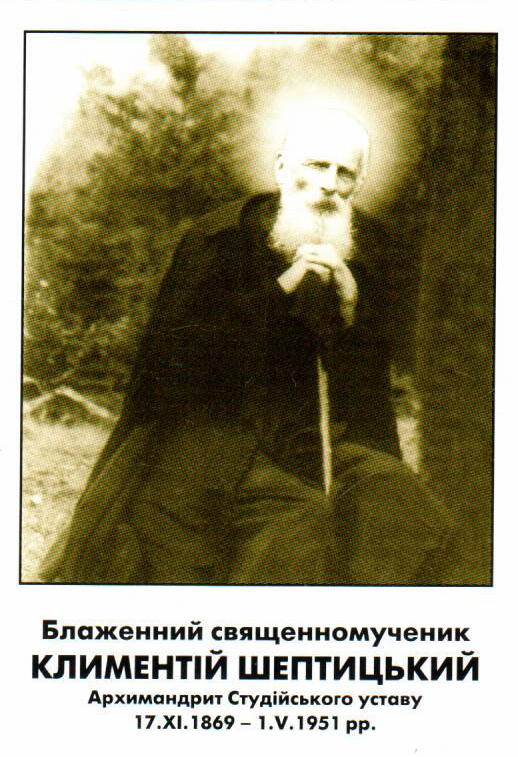

Image of Father Klymentiy after his beatification.

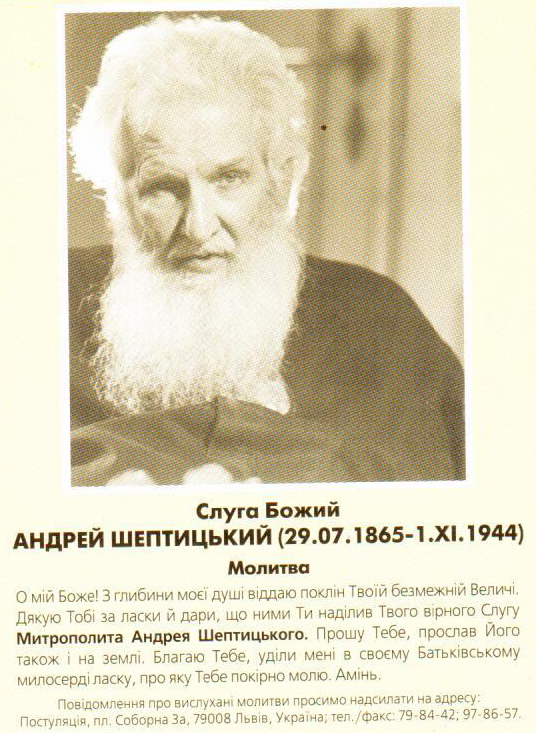

Metropolitan Andrei after his enthronement.

An image of Metropolitan Andrei with a printed prayer that was distributed to the faithful.

The Sheptytsky brothers’ sacrifice paved the way for future generations in independent Ukraine. As a result of their efforts, the Greek Catholic Church today plays a large role not only in western Ukraine but throughout the country. I would not rule out that the Church will one day be seen not as an obstacle along the path to uniting Eastern (Orthodox) Christianity with Western (Roman Catholic) Christianity, but as proof that what divides Christians of eastern and western Europe comes not from their different understandings of the dogma of their faith, but is far more the result of disputes that often have little to do with faith and religion.

Insufficient attention has been paid to this matter in research on Metropolitan Andrei. As I mentioned earlier, there are many monographs dedicated to the figure of Andrei Sheptytsky. I consider two of these to be particularly valuable: one published in Canada and a recently published book by a Ukrainian scholar.4 In both of these works, the central themes are the juxtaposition of ideals and values, and the prosaic realities of life and the demands of the time in which Sheptytsky lived and worked. This is also why it is worth giving more attention to Brother Klymentiy, who remained in his brother’s shadow for decades. To the broader public, he was essentially unknown, but it was he who John Paul II beatified during his pilgrimage to Ukraine in 2001. He was offered up together with another Ukrainian priest, Omelian Kovch, who during the war saved both Poles and Jews from the Nazi Germans and their collaborators. For this, Kovch was sent to the German concentration camp Majdanek. Although, thanks to the efforts of German priests and monks, he was given the chance to leave the camp under the condition that he would not get involved in political affairs, he refused. In a famous letter to the people who had been working towards his release, he explained that the prisoners in the camp needed him more than those who remained outside its fences. Omelian Kovch’s purpose in life was helping those who were in need. He died of emaciation and illness a few weeks before the camp’s liberation. The pope recognized Klymentiy Sheptytsky and Omelian Kovch as martyrs.

The Soviet authorities proposed to Klymentiy that he succeed his deceased brother Andrei as the head of the Greek Catholic Church and that he break off the Brest Union and bring the Kyivan metropolitanate into Russian Orthodoxy. Klymentiy Sheptytsky refused and was arrested. In May 1951, he died in prison in Vladimir on the Klyazma river. This was a place of isolation, whose ‘inmates’ were important political figures from various countries. He remained in his brother’s shadow even after his death. Only their beatification brought much deserved attention to Archimandrite Klymentiy Sheptytsky and the parish priest of Peremyshliany, Father Omelian Kovch.

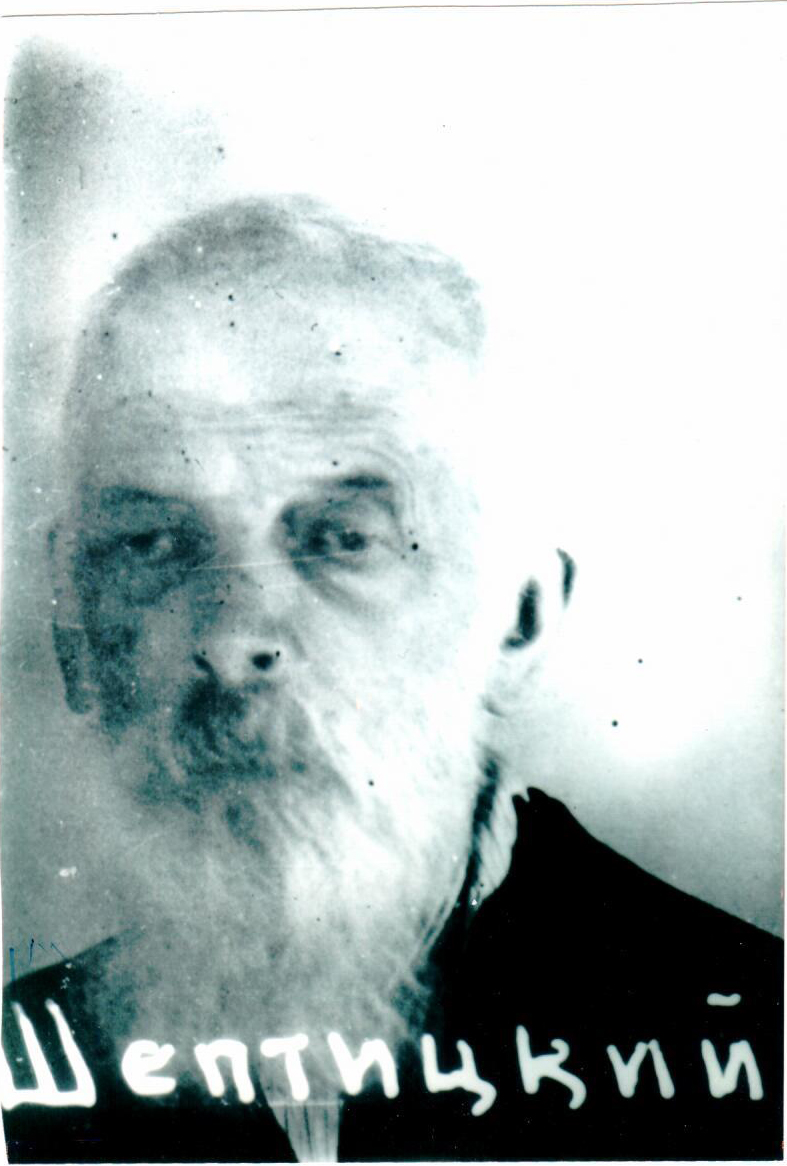

Prison in Stalinist Russia. Photograph of Father Klymentiy following his arrest, from the NKVD files.

On controversies in the evaluation of Metropolitan Andrei

The Sheptytskys began their work in the first decade of the last century. Over the next three turbulent decades, the political landscape would be altered beyond recognition. The Austro-Hungarian Empire disappeared and a host of new countries appeared on its former territory. Tsarist Russia was replaced first by the Russian Federation and then, in early 1923, the USSR. This did not happen without fratricidal struggles – for instance, the Polish-Ukrainian war over Lviv. In Eastern Galicia, governments and then occupiers changed like the patterns in a kaleidoscope. After the First World War, when the Austrians left, Eastern Galicia and Lviv became part of the Polish state, although the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic had laid claim to the city. In accordance with the Secret Protocols of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August 1939, Eastern Galicia was incorporated into the Soviet Union. After the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941, Lviv found itself in the hands of the Nazis. After the Second World War, Poland lost Lviv and Vilnius, along with 48 per cent of its pre-war territory; the territorial gains in the north and west at the expense of Prussia were a sort of compensation for the lands lost in the East. Cities in the eastern territories of Poland were inhabited mainly by Poles and Jews, and small towns mainly by Jews, while the Ukrainian population lived predominantly in the countryside. In Eastern Galicia, the rural population was the majority.

The Soviet authorities – ideologically internationalist – used Ukrainian nationalism mainly against the Poles. They consciously and instrumentally aroused anti-Polish and anti-Semitic sentiments, which led to large-scale pogroms against both Jews and Poles. The Soviet authorities also stoked conflicts between peasants and landowners. The NKVD killed Leon Szeptycki and his wife, the owners of the Szeptycki Palace in Przyłbice. It took local peasants nearly a week to summon the courage to take their remains from the Palace park and bury them. For the brothers who remained alive, Andrei and Klymentiy, this was a psychological shock, a testament to extreme barbarism that – it seemed – nothing could match.

Metropolitan Andrei’s behaviour towards the Germans after their arrival in Lviv in June 1941 was a reaction to what he had witnessed during the Soviet occupation. Andrei Sheptytsky welcomed the Wehrmacht as an army that, he believed, would represent European civilization. Both Sheptytsky brothers knew Austria and Germany. They had studied in Breslau (now Wrocław), Munich and Vienna. They had German and Austrian friends. They could not imagine that the Bolsheviks could be followed by something still worse. The Germans’ arrival was accompanied by the hope that the Third Reich would recognize an independent Ukraine.

The Metropolitan is often reproached – understandably so – for welcoming the Wehrmacht to Lviv in summer 1941. Only a few scholars noted that he was alone among important Catholic hierarchs to write to Pius XII in 1942, informing the pope that ‘the German authorities are evil, truly diabolic, and probably to an even greater degree than the Bolsheviks […] For a year at least there has not been a single day that passed without them committing the most heinous crimes, murder, theft and plunder, confiscation, and extortion. The primary victims are the Jews. The number of Jews murdered in our small country has definitely already exceeded two hundred thousand. As the army moved eastward the number of victims grew. In Kyiv, in the course of a few days, up to 130 thousand men, women, and children were exterminated. Every small town in Ukraine has witnessed similar massacres, and this has already been going on for a year.’5

In 1981, Canadian researcher Iroida Wynnycka interviewed the doorman of the Unev Monastery, Lavrentii Kuzyk.6 Kuzyk was perhaps the first person I saw when I got to the monastery as a boy. He was a simple peasant who – as one can see from the interview – had an innate sensitivity to human suffering. When he talks about his turbulent and difficult life, Lavrentii speaks most about saving Jewish children during the Second World War. At one point he mentions a gathering of the monks, during which Brother Klymentiy Sheptytsky – then still ihumen – asked, ‘Who will help the Jews?’ ‘There were 120 monks there,’ recalls Brother Kuzyk. ‘Everyone stood up.’ The very same reaction on the part of the monastic community is also mentioned by David Kahane.7 The fact that everyone stood up did not mean that everyone was actively involved in helping, but it attests to the mood and atmosphere. Since someone they all respected greatly, whom they saw as the highest authority, expected help from them, everyone voiced their readiness. Undoubtedly, there were some who did not feel positively towards Jews; after all, the monks were not totally separate from their environment, and as a rule they came from poor, rural Galician families. Among those who volunteered to help, Father Klymentiy chose only a few of the most trusted. Some of them, such as Father Marko Stek or my guardian Brother Danyil (Tymchyn), were, like Brother Klymentiy, posthumously distinguished with the Medal of the Righteous among the Nations.

Helping to save people would have been unthinkable without the personal engagement, spiritual encouragement, and material support of the Metropolitan. Despite this, Andrei Sheptytsky has still not been sufficiently recognized – even seventy years after his death. In searching for an answer as to why this is the case and why the recognition of his service continues to elicit opposition both in the beatification process and in including him among the Righteous of the Nations, it would be important to find out what was given to the Holy See and Yad Vashem by the Soviet Secret Services, the NKVD and KGB, as well as those of other communist countries.

Like any distinguished figure, Andrei Sheptytsky also made mistakes. However, if it was deemed possible to recognize the conduct of Oskar Schindler, who was awarded the Golden Medal of the Nazi Party – which undoubtedly helped him gain the rights to open factories, where he employed Jews and thus forestalled their inevitable death – then it is crucial to ask why similar recognition is denied to Andrei Sheptytsky. The Nazi uniform and medal protected Schindler, giving him a pass of safe conduct. The Metropolitan risked his life and those of his assistants, who could have been killed at any moment without any court involvement, which is what happened to thousands of people guided by the Christian values of compassion and mercy. Andrei and Klymentiy Sheptytsky risked much more than Schindler. They saved innocent people at their own expense, of their own will, and they did it selflessly.8

This resistance and opposition to recognizing the services of Metropolitan Sheptytsky will probably fade. In the future, new generations will decide how to evaluate the public life of the past. New generations and new scholars will look at the whole matter with distance and will judge people and affairs without stubbornness, with more objectivity. The Polish writer Eustachy Rylski once wrote that, ‘Fond memories do not depend on themselves. If they are unsupported they die, unlike infamy, which lives off of whatever falls to it, or even off of itself. Fond memories are finicky. They are like beauty: unprotected, they pass, before you notice. But ugliness persists, as unmovable as a boulder.’9 Sometimes people need to feel that they are better, morally superior, and disregard the notion that fabricated ‘facts’ about a person might be entirely fictitious. They were meant to serve a nefarious purpose – infamous reproach and character assassination; and they continue to be repeated – thoughtlessly and uncritically.

The Sheptytskys’ approach towards Ukrainian nationalism

Nationalism forms among groups of people with a similar history, language, or aspirations. As a rule, the nationalisms of European nations present themselves in opposition to someone. Ukrainian nationalism was not created by the Russians, but it was used by them. On the Polish–Ukrainian border, nationalism was largely constructed in opposition to the Poles. In Ukrainian national mythology and tradition, Poles were the nation of the nobility. In a certain sense, this was not a myth, but reality. Around Kyiv there were not many Poles, but there were many Polish manor houses.

Ukrainian national identity was also formed in opposition to the Russian Empire. Taras Shevchenko was not repressed by the Poles, but was internally exiled by the tsarist regime for writing poetry in Ukrainian. In 1876, the Tsar, who was taking the cure in Bad Ems (Germany), issued a decree that not only prohibited the use of the ‘Little Russian’ dialect – that is, the Ukrainian language – but even the use of the word ‘Ukraine’. The use of this ‘dialect’ was only permitted in old religious songs, or in the old church language, which paradoxically demonstrated – contrary to the Tsar’s intentions – what the roots of Russian culture, Orthodoxy, and the East Slavic languages really were.

Ukrainian nationalism arose at the same time as other nationalisms in Europe – in Germany and Italy, in the Czech lands and Poland, in Lithuania and Latvia, and in many other regions of Central and Eastern Europe. The Tsar prohibited the use of Ukrainian language, but the great poetry of Shevchenko and other authors was written in Ukrainian. Poets and writers were seen in Ukraine as prophets of a sort – the spiritual leaders of the modern nation that was taking shape. As a result, in the nineteenth century, Ukrainian poetry was printed in Geneva and smuggled to Kyiv in packages of Avada cigarette papers, whose small size (55x85mm) made it easier to get into the country and distribute. After the revolution, the Bolshevik authorities abolished these decrees. A brief era of Ukrainization came to an end when Stalin, who saw himself as an expert on matters of nationality, recognized the resurgence of Ukrainian culture as a threat to his empire and reintroduced Russification. The Ukrainian elite was shot or sent to Siberia.

But there is a fundamental difference between the awakening of national consciousness on the one hand and chauvinist aggressive nationalism on the other. Nationalism always looks for external and internal enemies. In Ukraine, the external enemies were Russia and Poland, while the internal enemy were the Jews. In his 1942 sermon, which was read aloud in all Greek Catholic churches, Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky gave an exegesis of the fifth commandment: thou shalt not kill. At a time when all human and divine laws were being trampled upon, he said, ‘Those who delude themselves and others that political killing is not a sin do so in a strange manner, as if politics releases a man from obedience to God’s law and justifies a crime that is abhorrent to human nature. This is not so.’10 The Metropolitan called Ukrainian killers cursed. He had the courage to loudly condemn the spreading evil, the crime, and the criminals, when others kept quiet out of fear. He sought to save and did save innocent people, he condemned their killers, and he did not spare harsh words towards his own society.

Seventy-five years have passed since November 1942, when Andrei Sheptytsky wrote those letters and delivered his courageous homilies, opposing murder and dedicating his own life and that of an entire community to saving innocent people. Many Poles – and, I think, Ukrainians – ask themselves: Why was his plea ineffective? Why, in spite of his wrathful words, were mass murders committed in Podolia and Volhynia? I don’t have a simple answer to that. One reason, certainly, is that people listen to figures of authority when they say what people want to hear. If Andrei Sheptytsky had made an ardent, nationalist appeal, he would have been recognized as a national hero. What is certain is that he said unpopular things during the war.

Klymentiy recognized his brother’s authority, was his assistant, and carried out his will, but he did not have any aspirations to play the role of spiritual leader of the Greek Catholic community. After Andrei’s death, he rejected the Soviet authorities’ suggestion that he occupy the Metropolitan’s throne in Lviv and unequivocally supported the candidacy of Iosyf Slipyi, whom Andrei had designated as his successor before World War II and had sought the pope’s approval in the form of a special bull.

The eminent Russian writer Boris Strugatsky published an essay over twenty years ago entitled Caution, Plague, in which he observed that ‘We live in dangerous times, times of rampant plague… Can the course of history be reversed? Surely it can, if millions of people want it.’11 The Sheptytsky brothers tried to influence millions. They had the courage to confront the evil that was rampant not only among the occupiers. They paid a high price for being faithful to their convictions both in life and in death. In Ukraine today, their lives and self-sacrifices are held up as an example of how, even in difficult and dramatic times, one can and should be decent.

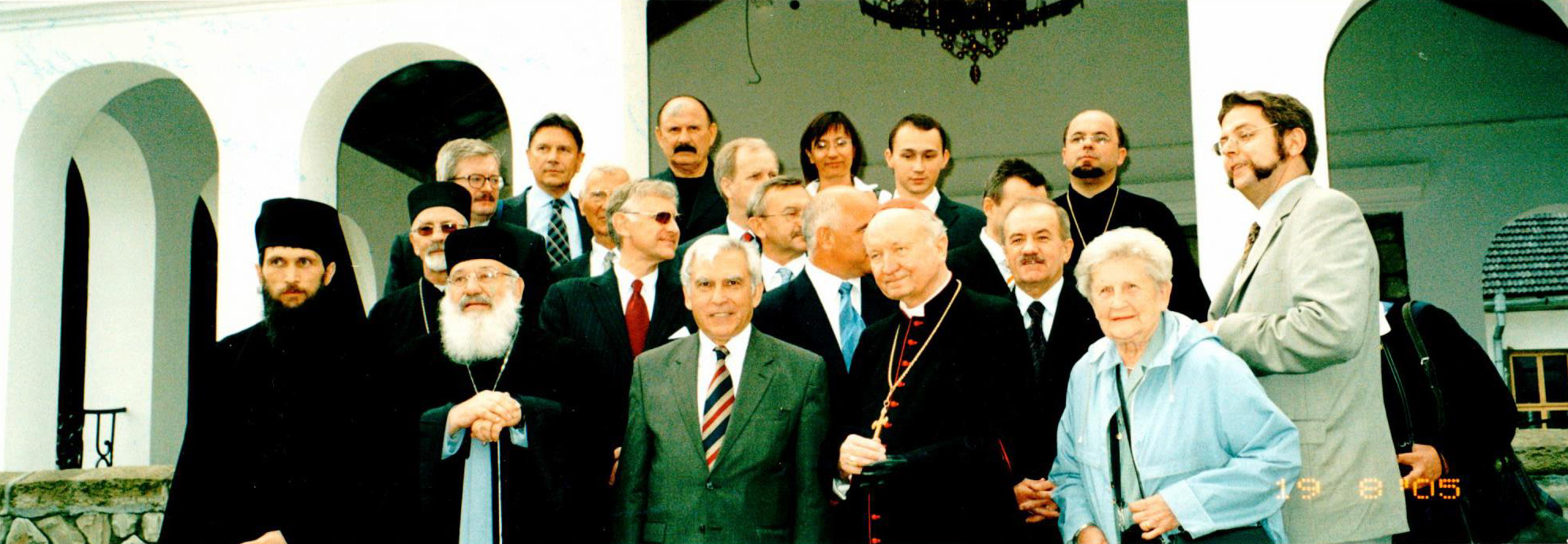

Unev. On the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, Adam Daniel Rotfeld spoke after mass in front of the altar at Cardinal Husar’s invitation.

Adam Daniel Rotfeld with descendants of the Szeptycki family.

Unev. Cardinal Lubomyr Husar, head of the Greek Catholic Church, and Cardinal Jaworski, Metropolitan of the Roman Catholic Church in Lviv, together with the Szeptycki family, after the ceremonial unveiling of a brass plaque honouring both Sheptytsky brothers for saving Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish children during World War II (19.08.2004).

I am grateful to Piotr Kubasiak for the conversation we held in December 2016 at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. The recording of this conversation was the basis for this essay. I would also like to express my thanks to Father Stefan Batruch – Greek Catholic priest from Lublin, and the Chameides brothers – Herbert (now Zwi) from Melbourne and Leon from West Hartford (US) – as well as Maciej Szeptycki, President of the Szeptycki Family Foundation, for their observations, suggestion, and clarifications, which were taken into account in the final version of this essay.

As part of the Ukraine in European Dialogue program, Polish intellectual and European Security negotiator Adam Daniel Rotfeld spent Autumn 2016 in Vienna at the invitation of the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) as Sheptytsky Senior Visiting Fellow. The fellowship is named in honour of Andrei Sheptytsky, Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church from 1901–1944. Rotfeld is one of the few people alive today who came into contact with the brother of the Lviv Metropolitan, Brother Klymentiy, Archimandrite of the Studite Order. It was his life and person that Rotfeld focused on during his stay in Vienna.

All photographs and illustrations are from the author’s private archive.

See Peter Galadza (ed.), Archbishop Andrei Sheptytsky and the Ukrainian Jewish Bond, Ottawa 2014.

Kurt I. Lewin: Przeżyłem: Saga Świętego Jura spisana w roku 1946 [I survived. The St. George Saga Written in 1946], Wyd. ‘Zeszyty Literackie’, Warsaw 2006; Leon Chameides: Strangers in Many Lands: The Story of a Jewish Family in Turbulent Times, [s.l.]. Printed in the United States, 2012.

Leszek Allerhand, Żydzi Lwowa: Opowieść [The Jews of Lviv: A Story], Kraków/Warsaw 2010.

Paul Robert Magocsi (ed.), Morality and Reality: The Life and Times of Andrei Sheptytsky, Edmonton 1989; Liliana Hentosh: Mytropolyt Sheptyts’kyi 1923–1939: Vyprobuvannia Idealiv [Metropolitan Sheptytsky 1923–1939: Testing Ideals], Lviv 2015.

Letter published in: Maria H. Szeptycka and Marek Skórka OSBM (eds.), Metropolita Andrzej Szeptycki: Pisma wybrane [Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky: Selected Letters], Kraków 2000, pp.399–400.

This conversation was part of the series ‘Oral histories of Ukrainian political émigrés in Canada’ and was published in Ukraina Moderna v. 4–5.

David Kahane, Lvov Ghetto Diary. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst 1990, p. 136.

Yad Vashem’s arguments were capably refuted by Julian Bussgang in his essay ‘Metropolitan Sheptytsky: A Reassessment’, Polin, 21/2009].

Eustachy Rylski, Warunek [The Condition], Warsaw 2005, 246.

Andrei Sheptytsky, ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’, https://training.ehri-project.eu/sites/training.ehri-project.eu/files/EHRI_Ua_D03_Sheptyts%27kyi_Nov_1942_0.pdf.

Boris Strugacki Caution, Plague (originally published in ‘Nevskoye Vremya’ – quoted after the Polish translation in ‘Gazeta Wyborcza’, Magazyn Świąteczny, February 3, 2017).

Published 12 July 2017

Original in Polish

Translated by

Kate Younger

First published by Eurozine (English version); Znak (Polish version)

© Adam Daniel Rotfeld / IWM / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Whether defending human rights on an international stage, checking facts from the frontline, processing traumatic experiences over a lifetime, or even questioning the language you have spoken since childhood – all matter in the collective fight for justice.

Time to live

Ukrainian cuisine, literature and cafés

Defending territory in war expands beyond physical frontlines to include cultural ground. Reclaiming signature dishes, language and public space contests their colonial assumption. Upholding traditions and retaining small home comforts takes on greater significance.