Since his return to power in 2010, Viktor Orbán has meticulously unravelled the rule of law and media pluralism, while holding the EU at bay. A short history of a decade’s attacks on the free press in Hungary.

The mayor of Gdańsk has long been target of a smear campaign in national media. Yet the harsh reaction of state propaganda after his death surprised even some supporters of the government.

The mayor of Gdańsk, Paweł Adamowicz, died last Monday. The 53-year-old politician had been stabbed the previous evening by a 27-year-old man on the stage of a charity event. After the attack, his assailant, an ex-convict, took the microphone and yelled that he had been unjustly jailed and tortured by the city’s ruling party. And so Adamowicz had to die. The country was in shock. Memorial events and silent marches took place across Poland and beyond.

Investigators are probing the attacker’s motive. Yet, the relationship between the deadly knife attack in Gdańsk and the radicalisation of Polish society since 2015 is plain enough. Adamowicz himself, his city, and the charity event at which he was murdered, have for the last three years been targets of organized hate campaigns, which hark back to the darkest chapter of modern Polish history.

The late Paweł Adamowicz (2018). Photo source: Wiki commons

For outside observers, it can be hard to grasp just how deeply the Polish media landscape has changed since 2010, and even more so since 2015. Rightwing and far-right media outlets mushroomed in the wake of the Smoleńsk air crash in April 2010, in which ninety-six prominent figures of Polish political and public life died, including then-President of Poland Lech Kaczyński. Between 2011 and 2013 alone, three new weeklies, one monthly and a television channel were founded, all selling conspiracy theories, promoting xenophobia and driving the PiS brand of identity politics. After the legislative elections in late 2015, the public radio and television were put at the disposal of the ruling party. The central role was to be played by the long-standing fixture Wiadomości (News), broadcast daily at 7:30pm, which is many Poles’ chief source of information. The programme’s selection of themes, production techniques and news tickers will surely go down in the history of Polish propaganda. Journalist Krzysztof Leski, who goes to the trouble of analysing Wiadomości every evening, has documented 100 news reports in 2018 alone in which Paweł Adamowicz was portrayed as ‘criminal’, ‘corrupt’, and a ‘bribetaker’. Not one of the many charges levelled against him in this way have ever been substantiated by investigators.

Anyone wondering why Adamowicz didn’t simply take legal action against the smear campaign waged by the public television should bear in mind that these allegations only represent a small portion of the aggression deployed against him. In July 2017, when Adamowicz and ten other mayors signed an open letter calling for Poland to welcome refugees, the fascist organisation All-Polish Youth (Młodzież Wszechpolska) pronounced him dead. The young fascists uploaded death certificates online, complete with photos and personal information of all the signatories to the open letter. Adamowicz reported All-Polish Youth to the police. But on 9 January 2019 the case was closed: the Gdańsk public prosecutor saw the act as being neither aggressive nor potentially threatening, calling it merely an ‘expression of discontent’. This decision is emblematic of the approach taken by Polish authorities towards hate speech: while laws against it do exist, those charged under them are virtually never convicted.

The liberal values that Adamowicz stood for were a key factor in his becoming a hate object: but they were not the only reason. Adamowicz was also hated for his origins. Gdańsk is where Solidarność was born; it is where Lech Wałęsa was active; it is the home of Donald Tusk and the site of the flagship cultural projects of the Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, PO), ruling in Poland between 2007 and 2015 – all of which are the bêtes noires of the PiS government and its supporters.

Back in 1998, when a 33-year-old Adamowicz was elected mayor of Gdańsk for the first time, the port city didn’t enjoy a particularly good reputation. The Gdańsk Shipyard had been one of the most spectacular victims of the privatisation, the city was plagued by unemployment and despair, and some districts were becoming no-go areas. Over the last 20 years, not only have quality of life indicators advanced significantly. The city’s image has improved, too. In 2009, many European capitals proudly displayed posters reading ‘It started in Gdańsk’. Poland’s campaign of cultural diplomacy was intended to overwrite the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall with the foundation of Solidarność nine years previously, in order to foreground the Polish contribution to the collapse of communism in European memory. The effort wasn’t entirely successful, but Gdańsk’s international profile was increased nevertheless. Opened in 2014, the European Solidarity Centre (Europejskie Centrum Solidarności), a museum of the history of the trade union, incorporating its central archive and an education centre, draws tourists from around the world. Even more successful has the Museum of the Second World War (Muzeum II Wojny Światowej) proven – a kind of response from the PO to the Warsaw Uprising Museum, which exists in the Polish capital since 2004 and rightly associated with the politics of memory pursued by PiS. When the PiS government moved to dismiss Paweł Machcewicz, founding director of the Museum of the Second World War, in order to ‘nationalize’ his transnational exposition, Adamowicz was able to block them for a while. His efforts made it possible to open the museum in early 2017 in the form originally envisioned by Machcewicz. The conservative hatred for Adamowicz grew and grew.

Even the spot where the mayor of Gdańsk was attacked on 13 January says a lot about the radicalization of Polish society. This was not just any charity event, but the most successful charitable undertaking in recent Polish history called the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity (Wielka Orkiestra Świątecznej Pomocy). It was founded by the Gdańsk-born journalist and festival manager Jurek Owsiak in 1993. Every second Sunday in January the Great Orchestra raises money to equip ailing Polish hospitals. This year, around 130,000 volunteers, young and old, famous and unknown, were involved. New records are set almost every year. In 2018, up to 30 million euro were collected. The Orchestra’s emblem – a red heart with white sign on it – can be seen today in almost every hospital in Poland. Countless lives have been saved this way.

Over the years, the second Sunday in January has become a national festival, with concerts, auctions and more, covered all day by the public television. But this tradition was ended abruptly in January 2016. After PiS took over the public TV broadcaster, collaboration with the Orchestra was terminated, and the private channel TVN took over the role instead. Jurek Owsiak suddenly fell victim to a volley of brutal attacks from the government and its supporters in the media and the Catholic church. The parallel with Viktor Orbán’s antisemitic campaign against the US philanthropist George Soros is stark. To take just one example: shortly before 8pm on 10 January 2019, the public television broadcast a satirical segment in which Owsiak was portrayed as a remote-controlled marionette, gathering up the money of naive Poles and presenting it to a PO politician who had been the mayor of Warsaw from 2006 to 2018. Some of the banknotes Owsiak handed over were decorated with Stars of David: a nod to the widespread rightwing belief that Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz is of Jewish descent. Three days after this broadcast Paweł Adamowicz stood on a market square in Gdańsk with a Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity collection tin in his hand – as he does every year – to thank the people of the city for their generosity. Shortly after 8pm he was stabbed. After Adamowicz’s death, Owsiak resigned from the Orchestra. The witch-hunt had proven too much, even for this resolutely-optimistic man, who always radiated goodwill through his trademark red glasses.

Can Adamowicz’s death bring calm to a divided Polish society? Many Poles asked the same question after the April 2005 death of John Paul II, and in the wake of the Smoleńsk air disaster five years later. In both cases, the country came to a halt for a few days, gripped by grief and shock. This time, belief in the reconciliatory power of death was shorter-lived. On the very day of Adamowicz’s death, the aforementioned Wiadomości programme broadcast a series of short news reports that placed the blame for the events in Gdańsk squarely on the shoulders of Tusk and Owsiak. Until now, many observers have thought it was tasteless and disproportionate to compare the PiS government’s communications policy with that of the latter half of the 1940s, when the Polish Communists’ propaganda machine was operating in high gear. After last Monday night, even some journalists supporting PiS were repulsed. How long their disgust will last, is another matter though.

Paweł Adamowicz was a founder of Eurozine network member journal New Eastern Europe and supported the Eurozine’ annual meeting of cultural journals in 2016. For a summary of commentaries on his assassination, read our article.

Published 24 January 2019

Original in English

Translated by

Edward Maltby

First published by Merkur blog 17 January 2019

Contributed by Merkur © Kornelia Kończal / Merkur / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Since his return to power in 2010, Viktor Orbán has meticulously unravelled the rule of law and media pluralism, while holding the EU at bay. A short history of a decade’s attacks on the free press in Hungary.

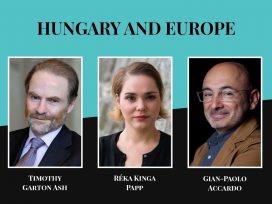

As a historian his expectations are gloomy, but as a political writer his optimism is strategic: Timothy Garton Ash talks about the European Union’s internal flaws and debates whether crises and collapses are always necessary for renewal.