When the future becomes unpopular

Global heating, environmental collapse and increasing global scarcity: no wonder the politics of perpetual advancement are failing to convince. Progressives must brace themselves for the return of some of their most detested ideas. But dismissing the nostalgists as reactionary can no longer be their response.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world

W.B. Yeats

In 2016, the Wall Street Journal reported that W.B. Yeats’ ‘The Second Coming’ had been quoted more often in the first seven months of that year than in any other year since the 1980s. It began trending on Twitter after the Brexit referendum, but went off the charts when the US elected a ‘rough beast’ as president.

Political apocalypticism has long been the domain of reactionaries. But all of a sudden, it appeared as though the mood expressed in notions of Eurabia, the Great Replacement, national suicide and cultural decay was spreading. Even progressives were talking about the death of democracy, the end of the liberal order, the return of fascism and post-truth. Doomsayers thrive at particular historical moments, as Europeans discovered in 1918. When crises are piling up, when one shock is followed by another, some embrace the end rather than try to weather the storm. Tapping into the aftershock of the Great War, Yeats’s 1919 poem describes this fatalism.

Isn’t the ‘crisis of democracy’ old news? Absolutely. It’s as ancient as democracy itself. Still, present circumstances raise the question as to whether we can look ahead to a time after the crisis. What does it mean to be ‘forward-looking’ in times like ours? The fear that drives much of contemporary political culture is caused by the disruptions that global complexity and a destabilised planet introduce into what was once called the body politic. Looking into a horizon of approaching global collapse, we are obliged to engage with scenarios for which we lack the intellectual resources to comprehend. Faced with a cognitive monstrosity, our political system lapses into its own ‘postfactual’ regime, as politicians and corporations continue to promise growth, progress, and business as usual.

San Francisco, September 2020. Author: Christopher Michel; source: Wikimedia Commons

Let’s assume that the current crises and popular revolts – all the anti-establishment protests of various colour – are indeed ushering in a new era. Maybe this is the moment when it dawns on us what the twenty-first century is going to be about. Among the plethora of movements that attack the system, the most successful have supplanted visions of utopia with what Zygmunt Bauman called retrotopia. As the future looms ever darker, we seek refuge in bygone days. Nostalgia becomes a substitute for hope. If what lies ahead is large-scale collapse, why not retreat to a golden past, where notions of sovereignty, control and identity are irrefutably embodied in an ethnically homogenous nation state?

Such reactions are attempts to evade the complexity and inherent contradictions of our time, and they can be very dangerous if converted into politics. Financial crisis, refugee crisis, pandemic – this is just the beginning. We can patrol our borders and build higher walls, but there is no escape. Even inside the sturdiest fortification, we will feel the effects of global heating, marine pollution, resource depletion and mass extinction. We will feel the ground we call home inevitably disappearing under our feet. It may very well be that the future as such will become increasingly unpopular.

Progressives would be advised to start recognising the ‘nostalgists’ as genuine opponents – as a political movement that is not simply going to vanish, but likely to foster novel and confusing constellations across the familiar left-right divide. Progressives have habitually brushed aside anything that seems ‘reactionary’, confident that history is on the side of progress. As if the course of history were inevitable, they have casually dismissed the ideological relics that the left-behinds couldn’t help clinging to. But one question will impose itself with increasing urgency: what does it mean to take a progressive approach to mounting challenges with no apparent solutions?

This touches upon the term ‘progressive’ itself. To be progressive implies that history is moving towards a better state of affairs – that we have the agency to continually improve society. Varieties of this faith crop up across the whole spectrum of progressive ideas, be it in revolution, humanism, enlightenment, free trade or technology. Ultimately, it is faith in secular redemption, often envisaged as a situation in which scarcity has been superseded.

One challenge the progressive ethos faces is how to retain a commitment to universalism, equality and the politics of redistribution and recognition in a world where scarcity is increasing. Progressives must prepare for their most detested ideas – including eugenics and social Darwinism – to filter back into the mainstream. What is now considered right-wing radicalism can, in a flash, gain a foothold among ‘respectable’ politicians. If this sort of politics continues to win popular support, it is not because the people are incurably racist. It is because the global village is starting to suffer from incurable scarcity. Many will find the fight to preserve their resources more empowering than the struggle to survive with less.

Politics without alternatives

Over the past four or five decades, the wealthy part of the world has been shaped by the twin processes that in the 1990s social scientists dubbed individualization and globalization. These have advanced personal autonomy and enabled escape from the shackles of traditional authority. But among large majorities, they have also contributed to a feeling of powerlessness, exacerbated by the palpable effects of systemic hyper-complexity and a collapsing biosphere. Now that unlimited growth and prosperity for all is losing credibility, we encounter the flipside of these processes.

What emerges is the perverse side-effect of what was once celebrated as ‘deregulation’: immense and rising inequalities coincide with unprecedented freedom for the wealthy few to sequester from the many. Neoliberal globalization may have started to reveal its true face in the trend among post-national oligarchs to bunker up in luxury, at a safe distance from the drowning and fighting masses.

A huge challenge for future democracy will be to combine the delicate balance between liberty and equality with the sweeping renunciation of privileges necessary to avert catastrophes. The gilets jaunes movement, which formed in reaction against fuel tax, was a striking portent. Pundits couldn’t agree on whether the yellow vests should be regarded as progressive or regressive, revolutionary or reactionary. Because privileges are so unequally distributed, the many who got the raw end will experience any ‘universal’ cutback as a direct affront.

It doesn’t help that environmentalism has become tangled up in consumer choice, identity and lifestyle. The gratification provided by ecological awareness can hardly be distinguished from the feeling of superiority over both the poor and the rich. Any forward-looking environmental democracy will run up against ferocious resistance, even if it were able to win all the scientists and experts over to its side. This is not because the masses are stupid, or because they have been fooled by evil manipulators. Rather, the feeling of being affronted provokes a heretic urge to contest official truths. Never before has this urge had such ample opportunity to fuel collective defiance as in the age of digital and social media.

An inherent contradiction of the neoliberal era is that a strong emphasis on individual freedom has been accompanied by an equally strong emphasis on a lack of political alternatives. ‘Modernization’, that magic formula, signified a technocratic mode of governance that aimed to adapt entire populations to the necessities ostensibly engendered by intensified globalization. Margaret Thatcher’s notorious phrase ‘there is no alternative’ referred to measures that economists claimed to have deduced from market laws.

Thatcherism can be debunked as pure ideology, but perhaps the coming democracy should not shy from similar rhetoric. In the future, the bravest politicians may be those who dare tell voters that there is no alternative, but without promising more individual freedom in return.

The collective project ahead

The coronavirus could be regarded as an agent of what the old left used to call ‘critique of the system’. All of a sudden, everything that neoliberalism had been telling us about what was necessary turned out to be invalid, in light of more dire necessities. The answers to urgent questions of collective survival cannot be structural adjustment programs and austerity measures. When the body politic suffers an exogenous shock, immense inequalities and low trust in the establishment will fan the embers that can flare up into civil war and state brutality.

In the collective project ahead, democracy’s survival will depend on its ability to placate these dangerous tensions. Growing planetary challenges will feed the forces threatening democracy from within, inciting fear and paranoia. The fragmentation of the public sphere enhances the potential for mobilized paranoia, as conspiracy theories go viral and gain immunity from logic. Planetary disruption (think of all the land that’s becoming uninhabitable; all the dormant coronaviruses that will spread as habitats are destroyed) will pave the way for a particular kind of indignant politician. With unswerving conviction, this kind of politician will be able to translate complexity into a dichotomy between friend and foe.

Politicians, networks and movements backed by capital interests will for the foreseeable future pose the loudest resistance to demands that we abandon privileges for the sake of the planet. Yet the biggest obstacle may not be the deniers, but the moderates who maintain that all can be salvaged without sacrifice. The political triumphs of an environmental democracy will come in the form of renunciations that obtain popular legitimacy by aligning with notions of fair distribution.

The question of fair distribution gets more complicated when considered on a global scale. A world in which scarcity is on the rise will hardly facilitate the global cooperation that necessity demands. Increasing scarcity is likely to offer increasing political resonance for misanthropy, anti-egalitarianism, tribalism and – ultimately – warmongering.

Some may dismiss such talk as reactionary. But it is rather an attempt to figure out how to react to reactionaries. After all, there is something to learn from them: their ability to ‘fan the sparks of hope in the past’, as Walter Benjamin put it. Maybe reactionaries are right in believing that the past can be restored in the present.

If that’s true, it would be good news for everyone who looks back at the hard-won victories of the social and environmental politics of the twentieth century. We need to work out what it means to be progressive in a world that offers no redemption. How do we remain modern amidst rising scarcity? This is the challenge facing the democrats of the twenty-first century.

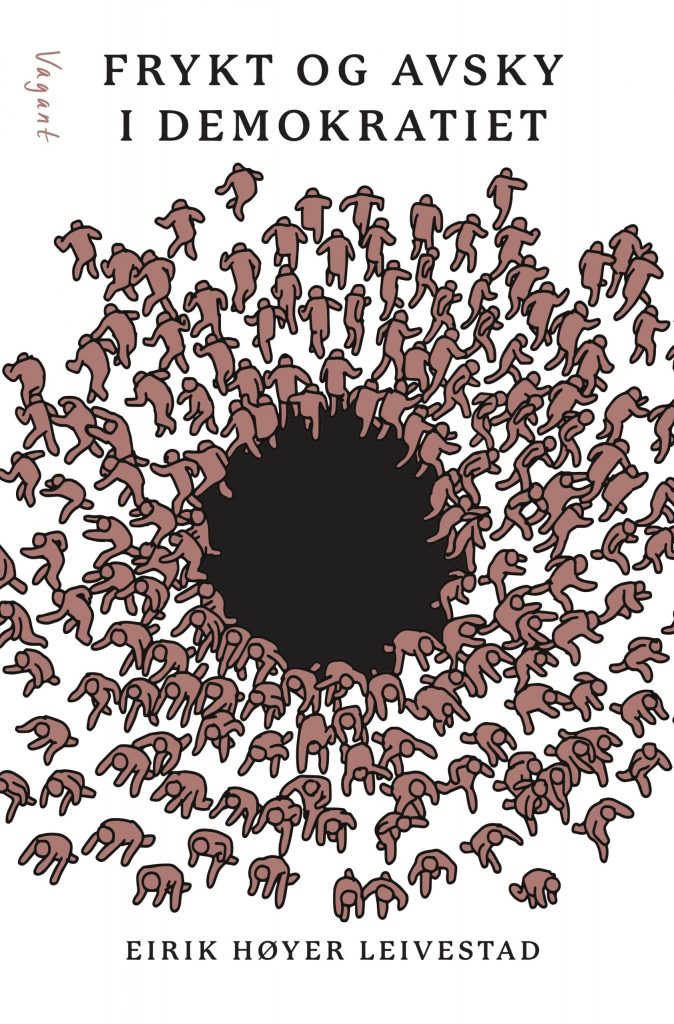

This essay is an abridged translation of the epilogue from Eirik Høyer Leivestad’s book Frykt og avsky i demokratiet (‘Fear and loathing in democracy’), Vagant 2020, out now in Norwegian.

Published 11 December 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Vagant © Eirik Høyer Leivestad / Vagant / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Clownism

Italy between instability and political transformation

Italy is the cradle of the far-right populism now seen across Europe. A system of perennially instable government engenders a form of politics that exploits Italians’ insecurities and distrust, while grinning all the time.

Petr Fiala’s replacement of Andrej Babiš as head of the Czech government is being seen as a refutation of the last four years of corruption, anti-Europeanism and populist instability. But this Manichean narrative, encouraged by the opposition during the campaign, ignores deeper tendencies within Czech politics.