War – what is it good for?

Vikerkaar 7–8/2021

‘Vikerkaar’ on the overlooked aspects of war – from the long-term impact on veterans to conflicts that rarely receive widespread coverage but cause no fewer casualties.

Whose rules determine how space is used or shared? Whose identity does a room express? The home is the place where power relations are established and contested. Ingrid Ruudi looks at how modern living space has shaped and been shaped by gender roles in Estonia.

With so many places suddenly off limits due to the virus, rarely have we been as acutely aware of space as we have this year. As one roams along empty streets, it becomes immediately apparent that space consists not only of architecture but equally of the social life within it. Domestic living space has undergone an even more intensive and paradoxical transformation. On the one hand, everyday life has contracted immensely, confining people to the four walls of their home. On the other hand, the scope of what can be accommodated within those four walls has grown considerably to include the office, the school, the café and the sports club. Whereas many people would normally spend only a fraction of the day at home, our relationship with our domestic space has now taken on a new and considerably weightier significance.

At the same time, inequality has been thrown into sharp relief. Whether in quarantine in a dingy one-room flat or a suburban house with a garden, alone, with companion(s), family or extended family, one’s domestic circumstances highlight both class and gender differences and imbalances. The home is the place where power relations are both established and contested, and this is true on the macro scale of public urban space too.

The ways in which a living space constitutes social relations are indeed diverse and raise a number of questions. Whose rules determine how the space is used or shared? Whose identity does a room express? Who is allowed egress and who must transgress? And, what about the issue of privacy? Some of these things may find physical expression in the space itself, obvious even to a stranger’s eye, but, more often than not, such spatial manifestations of human relations remain subtle. In what follows, I look at some instances of how modern living space has shaped and been shaped by gender roles.

While a ‘sense of homeliness’ based on home and family-centred intimacy is a long-held value, it assumed special significance in nineteenth century Europe. In urban settings, work shifted increasingly away from the home, and public and private spheres became much more differentiated than before, with child rearing being the only (re)productive activity still associated with the dwelling.

As a result, home came to be increasingly understood as a place for rest and relaxation, and the idea of privacy emerged as an appreciated and desirable quality. While the public sphere was the domain of men, the home remained the sphere of women. But even within a domestic setting, gender- and class-based distinctions were strongly demarcated – the higher the family’s social class, the clearer the demarcation.

In the context of nineteenth century Estonia, the ruling social class was of Baltic Germans who, regardless of the government of czarist Russia, had maintained their privileges as an elite and were the driving force in local economy, politics and culture. To a great extent, their dominance rested on thriving agricultural estates with elaborate manor houses as the embodiment of their cultural and social values.

Sangaste manor in southern Estonia, built in 1874–1881. Photo by Ivar Leidus via Wikimedia Commons.

However, from the second half of the nineteenth century, the identity issues of the Baltic Germans were growing increasingly complicated: on the one hand, ties were loosening with their German motherland, and on the other, their positions were increasingly challenged by the rising self-consciousness and economic capacity of local Estonians. This generated a situation where the Baltic Germans’ social life was more and more driven inwards, confined to their own social circles, representing a psychological withdrawal.1 The estate, and with it the notion of home, became ever more important constituent of identity, and the manor evolved into an ever more closed system that was an elaborate household complex both in terms of buildings and inhabitants.

Instead of the concept of the core family, the nineteenth century household incorporated an extended family, including close or distant relatives and other people associated with the family or working for the estate. A local peculiarity was a great number of ‘aunties’ or spinsters – the term could be applied to any unmarried woman over sixteen – because of a constant shortage of men largely due to long czarist military service.

Another local feature was the great social distance between children and adults. While keeping children away from family social life was common practice in the whole of Europe, it has been noted that the Baltic Germans kept their children at a much greater distance than was customary in Germany.2 At the same time, children spent most of the time with predominantly Estonian nurses and servants, which helped enhance coherence between nationalities and social classes.

This article was first published in the Estonian cultural journal ‘Vikerkaar’. Their 6/2020 issue focused on housing. Read our review of the issue here.

Lady Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake, who married into a Baltic German family and repeatedly visited her sister in Estonia, has left a written testament of the striking similarities between English and Estonian manor estate lifestyle and living conditions in her journals and correspondence. According to her, land and farming were at the core of the identity for both the English and Baltic German nobilities who highly valued hospitality and social entertaining at home.3

Describing the Estonian manor estates, she was impressed by their sumptuousness, especially the lavish interiors.4 With a lot of effort put into interior decoration, it is reasonable to assume that the distribution of the rooms and their furnishing principles also conformed to the widespread conventions that differentiated between masculine and feminine rooms – the tradition of considering the entrance hall, dining room, library, study, billiard room and smoking room ‘masculine’ spaces; while the drawing room, boudoir, music room, morning room and sleeping room came under the purview of women.

Each type of room was precisely coded according to its function, content and decoration. In Great Britain, this kind of division of space was well established by the beginning of the nineteenth century and remained virtually unchanged throughout the entire period.5 The ‘man’s rooms’ had to be grave, respectable and in dark colours, while the ‘woman’s rooms’ should be lighter, more colourful and decorative.

The drawing room was the most important, since it was where guests withdrew after dinner and, therefore, had to communicate to the guests an unambiguous image of their hosts’ identity. It was also where important social transactions took place, such as presenting marriageable daughters to potential suitors. Typically, the drawing room was decorated with numerous mirrors, bronze fittings and rich lighting. French or Oriental style cues were considered appropriate, while anything that bore the mark of ‘science’ in any form such as books, globes or maps was forbidden. Instead, expressions of artistic and less intellectual activities such as embroidery, sketches and music were favoured.

Dining room at Sangaste manor, end of 19th century. Courtesy of Valga Museum.

Impressive in size and decorated with family portraits, the dining room, in contrast, had to convey respectability and the family’s social standing. The proportions of the room were to be emphasised by the furniture, which had to be magnificent, durable and heavy. Oak was seen as ideal for expressing rugged masculinity; hunting trophies also often decorated the dining room. Indeed, it was the interior design of the dining room and the rituals of dinner that reaffirmed, both materially and symbolically, the firm links connecting hierarchical family relations, the gentry’s lifestyle and national identity.

In addition to the dining room, the family’s male identity was also reflected in the entrance hall and library. The former had to be weighty, simple and sombre in order to impress upon the visitor from their very first impression an understanding of the family’s respectability. Intellectual aspirations were to be expressed by the library. Its decorations included portraits of scientists and scholars associated with the owner’s profession and copies of ancient artworks. The library and study also often displayed family lineage in the form of portraits.

The woman’s boudoir, on the other hand, was not to contain a single piece of furniture that might favour prolonged activity such as a writing desk or bookshelves. Instead, the decoration of the room was meant to promote conversation, small handicrafts or the writing of short notes and poems at a small writing slope or dressing table.

Boudoir at the summer manor of Maarjamäe, beginning of 20th century. Courtesy of Estonian History Museum.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the differences between social ranks began to slowly diminish. In major cities like Tallinn and Tartu, the rise of the bourgeois population brought demand for apartments with three to four rooms, which were classified as small according to upper class standards. Furnishings became cheaper and a lot of goods became more attainable; however, this did not really mean democratization of the ideal, quite the contrary – the former apprentices tried hard to mimic their masters and the nouveau riche coveted all kinds of status symbols.6

Pretensions to respectability and normative formalities overruled comfort. As the social etiquette strictly required the differentiation of dining room from living room, and the head of the family might have needed a study as well, the majority of the apartment was reserved for ‘public’ functions while ‘private’ spaces such as bedrooms were cramped and overcrowded.

The rooms of Historicist and Jugendstil apartment buildings and villas display a clear hierarchy: public rooms such as the living room/hall, dining room with veranda and study/library (at times with a waiting room) are spacious and richly decorated with windows opening onto the street, while private spaces such as bedrooms are small and located towards the yard at the rear. The service zone of kitchen, serving room, servant’s room and bathroom is located towards the yard and often has a separate entrance.7

In 1915 the newspaper Tallinna Kaja (Echo of Tallinn) published recommendations on how to design the room of the head of the family that continue the earlier tradition of spatial segregation and gendered furnishing. Referring to Edvard Elenius, the Finnish ideologist of home design and rector of the School of Applied Arts in Turku, it wrote:

‘The master’s room is designed to be the working and reception room of the master, head of the family. Even in such a family where the master’s most important activities take place outside the home, in the office or school, he is still given his own private room. The internal management of the home requires its own little “office”, and the master’s room serves as such. … This room must be furnished fittingly for a study. Therefore, the master’s room must have the following furnishings: a writing desk, a writing chair, a bookcase or shelf, a sofa and sofa table, a couple of armchairs either next to the sofa table or some other smaller table, and if possible, one or two pillars [pedestals] for statues. … In the master’s room, it is not fitting to keep large numbers of various small utensils and decorations that give a cheerful and lively appearance to other rooms.’8

Nevertheless, luxurious upper-class living spaces were not the only ones characterized by gender-based segregation. Anthropologists have demonstrated that the division of rooms or parts of rooms based on gender characterizes the dwellings of most indigenous peoples,9 and the Estonian barn-dwelling (a long farmhouse comprising living rooms at one end and a threshing room at the other) was no exception.

An Estonian farmhouse displayed at the Estonian Open Air Museum. Photo by Sander Säde on Wikimedia Commons.

Even if the dwelling consisted of just one big room, it was mentally zoned: at the table, both the master and mistress of the house had their fixed places, and the hierarchy within the family was also marked by the location and character of the sleeping arrangements.10

Four aspects of modernity exercised the strongest influence on women’s domestic life.11 Increasing urbanization combined with gradually more standardized and less expensive architectural production made it possible for extensive suburbs to spring up, which was promoted as the ideal environment for raising children. Developments in medicine, including a better understanding of hygiene and obstetric care, provided women with improved living conditions, while the emergence of consumer culture increased both daily comfort and allowed for more diverse opportunities for self-expression through home design.

The influence of science across all aspects of life meant that the expert culture began to impact the private sphere. Now the home was to be organized according to scientific principles. Decisions concerning family life and housekeeping that had formerly been purely private came to be influenced by the opinions and recommendations of specialists such as government officials, health workers and other professionals. Home management gained a completely new meaning and the woman’s role as manager of the unit took on a new, professional colouring. A rationally organized and clean home was a marker of civilization, with improvements by women within the home a sign of civic contribution.

During the interwar period, substantial work on developing and reinterpreting environmental and spatial standards was done in Estonia, too. The progressive mindset of the growing middle class had to be reflected in architecture, but the aesthetic innovativeness of functionalism did not necessarily mean progressiveness in the social dimension of space. Rather, as material means improved, modern functionalist villas and apartment houses in the second half of the 1930s increasingly came to reflect a desire for a traditional bourgeois way of life (with their hierarchical room arrangements).

Assuming that designing his/her own house would most explicitly express the architect’s principles and ideals of living, it is worthwhile considering the dwellings of three architects of the period: Herbert Johanson (1884-1964), Olev Siinmaa (1881-1948) and Erika Nõva (1905-1987). As for their external appearances, both Johanson’s house in Tallinn (located at Toompuiestee 6 and built in 1929) and Siinmaa’s villa in Pärnu (located at Rüütli 1a and built between 1931-1933) are resplendently white and angular, using a geometrical play of form(s) and a flat roof. Both are undoubtedly far more modern than Nõva’s traditional-looking house at Mustamäe (located at Tähetorni 6 and constructed between 1937-1938), which, for practical reasons, includes a thatched roof (inexpensive reed was available) that resulted in an even more archaic looking building than had been designed originally.

The external appearance of Herbert Johanson’s house was so avant-garde in its day that newspaper articles had to be published in order to explain its new and modern aesthetics to the public. Its spatial organization, however, is conventional and unimaginative. Living spaces are located on both sides of a central corridor, with the bedrooms behind them; the study is located next to the entrance and there is a separate door and a tiny room behind the kitchen stove’s wall (i.e., a warm wall with flues in it for warm air to pass through before reaching the chimney) for the servant.

Olev Siinmaa displays a notably better understanding of the modern way of life. For one, he was the only Estonian architect of the interwar period to follow the example of the Frankfurt kitchen – the infamous rational kitchen by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (1926) that was designed for Ernst May’s social housing units in Frankfurt but promoted internationally and exported in great numbers to France and Sweden.

The Frankfurt kitchen, a remake at the MAK, Vienna. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The tiny Frankfurt kitchen (measuring only 1.9 x 3.44 m) resulted from carefully calculating optimal dimensions and the placement of furniture and objects in order to minimize the number of necessary movements. A continuous countertop ran around the room; a rubbish bin stood right under the carving and chopping surface; and water from wet dishes was directed straight into a drain pipe.

In order to create a sense of spaciousness, there were no wall units; instead, the kitchen was fitted with metal drawers for dry ingredients, numerous hooks and electrical appliances, which were a novelty at the time. Easily cleanable materials, such as glass, metal, glazed tiles and aluminium guaranteed hygiene.

Similarly, Siinmaa’s villa in Pärnu has a continuous worktop that receives direct light from a window, a foldable ironing board and revolving stool, and ingeniously built-in cupboards and drawers. Between the kitchen and the dining room there is a built-in cupboard with a central opening through which food can be passed directly into the dining room on a revolving glass-topped surface. Right next to the cupboard is a door, the placement of which is less about the servant’s comfort or saving time than about making them invisible in the traditional sense. Food appears on the table, but the servants remain out of sight. Nevertheless, servants can enter the house through the same door as the family.

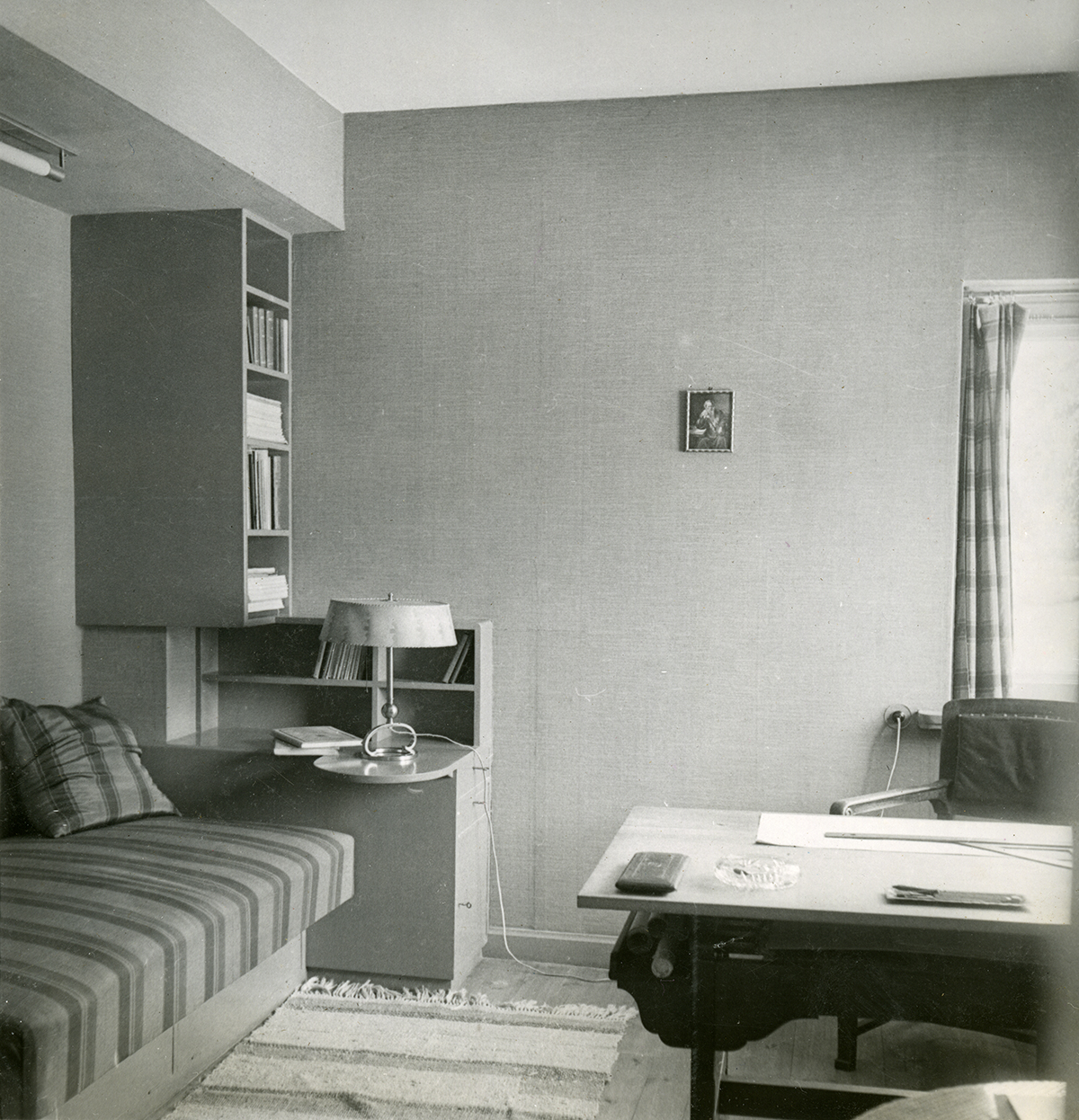

Ground floor study in architect Olev Siinmaa’s own house, 1930s. Courtesy of Museum of Estonian Architecture. (two images side by side, ground floor study to the left)

The general division of space in the living area is also more progressive in Siinmaa’s house. Although the raised floor of the living room marks a spatial hierarchy and demarcates the living space, dining and reception rooms follow social conventions. The rooms are nevertheless visually connected and they freely flow into one another. The architect also designed two study rooms for himself: one on the ground floor is meant for receiving clients, while another on the first floor is fit for more private reflection.

First floor study in architect Olev Siinmaa’s own house, 1930s. Courtesy of Museum of Estonian Architecture.

But where is the woman’s place of uninterrupted privacy? Even though upon completion of the house it was appreciatively noted in the press that the bedroom need not be merely a vacant room containing a magnificently covered bed during the day,12 the woman’s right to that room is still conditional and not exclusive. The classical description offered by Leslie Kanes Weisman is still valid:

‘From the master bedroom to the head of the table, the “man of the house/breadwinner” is afforded places of authority, privacy (his own study), and leisure (a hobby shop, a special lounge chair). A homemaker has no inviolable space of her own. She is attached to spaces of service. She is a hostess in the living room, a cook in the kitchen, a mother in the children’s room, a lover in the bedroom, a chauffeur in the garage.’13

Erika Nõva’s house aspires to a less formal division of space inside despite its more traditional exterior. The house was designed at a time when she had a day job, a private practice and two-year-old twins, and the spatial organisation clearly reflects the necessity to juggle these different roles.

The living floor is as open as possible, forming one multifunctional space that combines living room and working space with a dining niche at one end. The kitchen space is separated from the living area with a wall, but a round internal window in it enables the person working in the kitchen to keep an eye on children playing in the living room. The whole ground floor forms a continuous space, conforming to the idea of the open plan rigorously advocated by the architects of the modern movement as a spatial agent of democratization of social relations. Indeed, the less clearly defined the functions of the rooms, the greater the potential for flexible use patterns and equality in family relations.

Erika Nõva’s living room with interior window in the architect’s own house, 1930s. Courtesy of Museum of Estonian Architecture.

Nõva was a firm believer of women’s emancipation through better education in all areas of social and domestic life. She wrote numerous articles for the magazine Taluperenaine (The Farmhouse Mistress) and gave public lectures, aiming to encourage women to demand and create a more practical and balanced home. In the articles she advocated, among other things, living spaces with less rigidly defined purpose and often preferred practical, time-saving and down-to-earth design solutions to stylistic considerations. For her, the true spirit of functionalism lay in the practicality rather than aesthetics of the movement.

After World War II, the building of individual houses resumed from the mid-1950s despite the collectivist rhetoric of the Soviet Union. It was a desperate means to alleviate the chronic shortage of housing and, in Estonia, this change of policies was welcomed as an opportunity to redirect creative energy towards the private sphere as a kind of counterbalancing of the realities of occupation.

The traditionalist individual houses of the 1950s and the more modern ones of the 1960-70s mostly display fairly conventional spatial organization. Although the avant-garde architecture of the early Soviet era had involved some radical experiments aiming at, among other aspects, rethinking housing for gender equality, this never became a mainstream ideology, and the architecture of post-war individual houses certainly did not consider such issues.

The Soviet gender policy meant that women were emancipated in the public sphere, their full-time working and participation in social activities was actively encouraged, but subjected to conservative and paternalist attitudes in private life where they were still expected to fulfil the role of the main home-maker, cook and caretaker of children and the elderly.14 In reality, this simply translated into the ‘freedom’ to bear twice the workload.15 Accordingly, expectations for traditional gender roles show in spatial organization as well.

Another aspect affecting architectural solutions was strict spatial norms. All of the necessary elements had to be crammed within a small space: at first, a maximum 90m2 of total surface was allowed, with a maximum 60m2 of it designated for ‘useful space’ (i.e., kitchen, living room and bedrooms). The norms were later slightly expanded but still remained quite small for a private house, leading to attempts at tweaking the rules.

This mostly manifested in floor plans growing ever more elaborate to include all kinds of auxiliary and utility rooms that did not qualify as ‘useful’: hallways, attics, laundry and drying rooms, workshops, storages, etc. On the other hand, the abundance of hobby and utility rooms reflected the specific DIY culture of the era.

Whereas in western Europe, hobby spaces added from the 1970s onwards reflected the new DIY culture and an understanding of homemaking as a form of self-expression,16 in the Soviet context they resulted largely from a deficit of food, consumer goods and services: you had to have space to store vegetables and rooms to prepare conserves for the winter season, the ability and tools to repair anything broken in the household, and so on.

Toomas Rein’s postmodern private house with ample auxiliary rooms and a greenhouse, 1980s. Photo Arne Maasik, courtesy of Museum of Estonian Architecture.

Even in urban settings, private houses often had spacious greenhouses, while cellars became stores for necessary winter provisions (e.g., vegetables, fruit and preserves). While activities such as gardening, pickling and preserving fruit were done by women, men took care of house and car repair work, with the garage emerging as a male-oriented space. This is reflected by garages complete with repair pits, as well as by sizeable workshops in the basements of houses.

The garage – a safety valve for alleviating the dangerous pressures of suburban life – could be considered the most masculine type of room in the East as well as in the West. While in the Soviet realm it reflected the traditional expectations held for the male gender role, in the West in the 1980-90s it started to be associated with male, unconventional innovation in general, feeding the image of works of genius – à la Apple, Amazon or Nirvana, all born in garages – coming into being from the periphery of society.17

Suburbanization has certainly been one of the post-socialist era’s most noteworthy tendencies. Due to favourable policies and aggressively marketed mortgage possibilities, inhabitants of mass-produced tower blocks started to be able to fulfil their desires for an idealized private house at the end of the 1990s. A construction boom of new private houses started and reached full momentum in the 2000s.

At first, many former summer cottages were adapted for year-round living, but the overwhelming majority of houses built during the period were new. Beginning in 2005, however, blocks of flats began cropping up.18

The privately-owned one-family house, which was favoured politically and economically, gave rise to a monofunctional suburban sprawl that reproduced traditional gender roles. Promoted as child-friendly, the suburban house demanded a much greater contribution of domestic work than urban apartments and was much more likely to promote a family model in which the man works outside the home while the woman stays home.

The managing of the suburban home demanded more time and effort than an apartment in the city – tasks usually falling upon women – and in the lack of public transportation, a car was a must – but primarily used by the male breadwinner commuting to work.

At the same time, the much-prided national ‘mother’s salary’ policy meant that a woman was eligible for paid maternity leave for up to one and a half years providing that she would not be engaged in any kind of part-time work. The pay continued if she delivered her next child within three years of the birth of the previous one, promoting young women to stay longer at home, keeping them off the job market and rendering them ineligible for a mortgage or devoid of means to afford their own place. Spatial, social and economic factors intertwined, placing mothers of young children into a dependent position.

In addition, urban sprawl tends towards homogeneity. Neighbourhood residents are likely to have similar economic backgrounds and the children in newly established suburbs with young parents tend to be of more or less the same age. People who are in poor health, unmarried or live non-normative lifestyles are unlikely to gain access to such areas.

Even today, most suburban houses reflect the traditional family structure: common areas comprise of a living room, kitchen, dining room and study, while non-communal areas consist of the (married) couple’s bedroom as well as the children’s room(s). The kitchen and living room have been joined in recent years, a reflection of the explosion of foodie culture in which food has been linked with socializing and entertainment. A servant’s room or cottage, however, has largely become a thing of the past.

Koda by Kodasema. Prefabricated house for single occupancy, 2010s. Photo Paul Kuimet, courtesy of Kodasema.

If we were to ask if there was any fundamentally new tendency in the modern private house landscape, I think it could be a house meant for only one person – either the villas of well-to-do single businessmen (and, more rarely, businesswomen), or the ever more widely spreading trend of micro-houses.

As a social norm, the separate phase of living on one’s own between leaving the childhood home and creating a home after marriage is a relatively new phenomenon; for the first time, the developers of mass-produced houses are beginning to see a single person as their possible client.

The individualism and nomadic and flexible way of life expressed in the modern ‘single age’ may, from the perspective of spatial solutions, lead to ascetic solutions catering to a minimum existence, where the home only fulfils the most basic functions and working and social life unfolds elsewhere – in a way, harking back to the ideology of the most basic cell of the radical avant-gardes of the 1920s.

On the other hand, it could also mean a total intertwinement of working and private life, with work colonizing any privacy in home offices – a tendency all the more exacerbated by the pandemic. This, of course, is not a danger in spaces of single occupancy – when homes become psychologically compressed to simultaneously serve as an office, a classroom and a café, it tends to rob the most privacy and control from those who had the least in the first place: women.

This article was supported by grant IUT 32-1 (’Experimental practices and theories in the visual and spatial culture of 20th and 21st century Estonia’) by the Estonian Research Council.

Heide W. Whelan, Adapting to modernity: family, caste and capitalism among the Baltic German nobility (Köln: Böhlau Verlag, 1999), pp. 228-230.

Ulrike Plath, ’Emad, ammed ja korsetid. Balti naised biidermeieri ajal’ [Mothers, Nurses, and Corsets: Baltic Women of the Biedermeier Age], in Eesti Kunstimuuseumi toimetised. Proceedings of the Art Museum of Estonia, 2011, No 1, pp. 153–168.

Elizabeth Eastlake, Letters from the Shores of the Baltic (London: John Murray, 1844), p. 58.

Ibid., p.37.

Juliet Kinchin, ‘Interiors: Nineteenth-Century Essays on the ‘Masculine’ and the ‘Feminine’ Room’, in Intimus. Interior Design Theory Reader, edited by Mark Taylor and Julieanna Preston (London: Wiley, 2006), pp. 168-172.

Ants Hein, ’Interjöör kui ajastu peegel’ [Interior as the Mirror of an Era], in Eesti kunsti ajalugu 4 (1840–1900) [History of Estonian Art 4 (1840–1900)], edited by Juta Keevallik (Tallinn: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia, 2019), p. 364.

Oliver Orro, Mart Siilivask, ‘Ruumist tapeetide ümber’ [About the Rooms Around the Wallpapers], in: Vabamüürlus, arhitektuur ja ajalooline interjöör. Uurimusi kunstist, tapeetidest ja Pistohlkorside perekonnast 18. sajandist 20. sajandi alguseni. Tartu linnamuuseumi aastaraamat 20. [Freemasonry, Architecture and Historical Interior. Studies of Art, Wallpapers and the Pistolkohrs Family from the 18th Century to the Beginning of the 20th Century. Tartu City Museum yearbook 20.] (Tartu: Tartu Linnamuuseum 2015), p. 59.

Peremehe tuba. Edv. Eleniuse järgi [The Master’s Room. According to Edv. Elenius], in Tallinna Kaja, 12.09.1915, pp. 572–574. I thank Oliver Orro for the reference.

Irene Cieraad, ‘Anthropology at Home’, in At Home. An Anthropology of Domestic Space, edited by Irene Cieraad (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999), p. 2.

Madli Maruste, ’Eesti talu kui kompass minevikku ja tulevikku’, In Maja, 2019, No 4, p. 41.

Judy Giles, The Parlour and the Suburb. Domestic Identities, Class, Femininity and Modernity (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), p. 22.

K. M., Praktiline elamu Pärnus. Majaomanik, 1936, No 1.

Leslie Kanes Weisman, ‘Women’s Environmental Rights: A Manifesto’, Making Room: Women and Architecture. Heresies, no. 3 (1981) pp. 6-8.

Katrin Kivimaa and Kädi Talvoja, Nõukogude naine Eesti kunstis / The Soviet Woman in Estonian Art (Tallinn: Estonian Art Museum, 2010).

Susan E. Reid, ‘Communist Comfort: Socialist Modernism and the Making of Cosy Homes in the Khrushchev Era’, in Homes and Homecomings. Gendered Histories of Domesticity and Return, edited by K. H. Adler and Carrie Hamilton (London: Wiley, 2010), pp. 11-44.

Tim Putnam, ‘Postmodern’ Home Life’, in At Home, pp. 144-152.

See also Anthony Morey and Volkan Alkanoglu, ‘Architectural Purgatory. The Car, the Garage, and the House’, in The Interior Architecture Theory Reader, edited by G. Marinic (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 327-333.

Kadri Leetmaa, Anneli Kährik, Mari Nuga, and Tiit Tammaru, ‘Suburbanization in the Tallinn Metropolitan Area’, in Confronting Suburbanization. Urban Decentralization in Postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe, edited by Kiril Stanilov and Luděk Sýkora (London: Wiley, 2014), pp. 192-224.

Published 23 December 2020

Original in Estonian

Translated by

Triinu Pakk

First published by Vikerkaar 6/2020

Contributed by Vikerkaar © Ingrid Ruudi / Vikerkaar / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

‘Vikerkaar’ on the overlooked aspects of war – from the long-term impact on veterans to conflicts that rarely receive widespread coverage but cause no fewer casualties.

How is whiteness constructed and why is it so fragile? What’s at stake in discussing colonial memory for eastern Europeans? Do they actually eat a lot of cabbage?