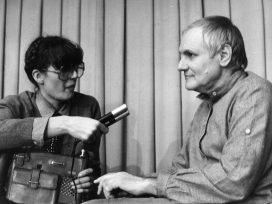

György Dragomán was born in Transylvania, Romania in 1973 and lives in Budapest, where he writes in Hungarian. He is currently visiting Helsinki as a guest of the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies. Dragomán’s break-through novel The White King received extensive media coverage and became a critics’ favourite globally. The protagonist, Djata, observes the workings of a nameless eastern European communist dictatorship from an eleven-year-old boy’s perspective while missing his father, who was taken away to a labour camp.

In his youth, as Dragomán himself moved from one eastern European country to another, he witnessed a series of changes on the borders that affected the names and polities of his home country and neighbouring nations.

“I was born in Transylvania, which has been a part of both Romania and Hungary as well as an independent nation. It is an exceptional area with a long history and a tolerant and diverse population, in both ethnic and religious terms. My family and I moved to Hungary in 1988 and I still live in Budapest with my wife and two children. My mother tongue is Hungarian, but my last name is actually Armenian, and means ‘translator'”, says Dragomán, himself a translator of Samuel Beckett and James Joyce, among others.

Dragomán emphasizes the fact that The White King is by no means an autobiographical work even though he, like Djata, grew up under an eastern European dictatorship in the 1980s.

The totalitarian regime is a violent game

The name of The White King comes from a chess piece Djata steals. The piece, which is in fact more like an ivory miniature sculpture, becomes a symbol of power and independence for Djata. The game of chess expands into a metaphor for the novel or even for the entire totalitarian regime – each piece has its position and purpose, there’s a strict hierarchy between the pieces and the aim of the game is to conquer the board. Unlike in chess, though, the rules of an authoritarian state constantly shift or remain entirely unknown.

The White King paints a vivid picture of the non-communication and constant doubt that make up the social reality of a socialist state. Some of the atrocities that take place are alluded to between the lines; some are thrown in the reader’s face as grotesquely precise representations of violence. All of which shows how in a totalitarian state, violence penetrates the entire society.

Djata’s world is filled with violence on every level: he plays brutal war-games with the neighbourhood boys and his teachers routinely use methods of corporal punishment as well as humiliation on their students. Peacefully queuing for oranges can turn into a lynching in a matter of seconds.

“It’s interesting how the language of violence functions and can define society. As a child I didn’t realize I was growing up in a very violent society, but actually it was an ultra-violent society even though violence was not so much physically present. But it was always present, it was in the air. You breathed it in and out and it became unconscious. In a way, real violence emerges when violence becomes so much a part of your consciousness, it becomes unconscious.”

Dragomán has had to rethink his own childhood after becoming a father himself. Djata’s as well as Dragomán’s own childhood were constructed around a strict hierarchy between children, a pecking order that defined interaction. His own children are growing up in a society where freedom is taken for granted.

“In my own childhood, the violence and the pecking order felt normal. Now that I have children of my own, I realize how different their interaction with other children is, how violence and power relations are much less present in their everyday lives. They play far less war games, whereas all of our games were about war in some way. In a way, I’m grateful for my own traumatizing childhood, but of course I don’t want my children to go through the same. Life is definitely happier if you’re not constantly traumatized. It is nice to see, however, that freedom is possible in a child’s frame of mind. They take freedom for granted, which of course it isn’t. Then again, maybe freedom is more easily lost, if you take it that way. We’ll see in time.”

The guessing game and hidden violence

Day-to-day reality in a communist state was defined by a long list of forbidden practices, objects and opinions, and the culture of informants that aimed to keep everyone in check. Naturally, no one knew the identity of the informants, so neighbours, distant relatives and co-workers were all suspicious by default. Keeping people in a constant state of mistrust is a form of exercising power according to the ancient principle of divide and conquer. Dragomán links this distrust to the violence of the system:

“Conversations were full of violence and nearly every subject was approached through it. A dictatorship functions just so; violence replaces communication in its entirety. Since nobody could be trusted, you were forced into this violent guessing game of whether they’ll hurt you or you them. It all started very early on, I can’t even remember any other type of conversation. This is all in retrospect of course, at the time it felt completely normal.”

Dragomán is very good at portraying the division between open, physical violence, and hidden violence that is apparent only on the level of speech and thought, and as a constant threat in everyday life.

“In some ways, the entire system’s rhetoric was based on violence. Peace was of course a big deal and the state’s rhetoric was always about peace, but there was always some battle involved. As a child I always had this terrible feeling that violence could emerge at any moment. Like in school, where during my childhood teachers still used canes. We weren’t caned often, but the threat was always present. I remember this teacher, who had a broken arm in a cast. I remember the story was that he’d broken it when hitting a child. This probably wasn’t true, but as a child, I believed the story completely.”

A society hungry for freedom and information

Limiting access to information is one of the key elements of any closed political system. In a communist dictatorship, censorship and propaganda functioned (and in some places still function) like well-maintained machines, even though the censored material may seem trivial and the propaganda naive.

These two means of mental control are combined in a story in The White King. Djata and his friend are watching a documentary film about the five-year plan, when a blackout hits, and the boys venture out and find a locked auditorium.

[H]e’d show me where the entrance was to that secret projectionist’s room in the cinema, the room his grandfather told him about, where they stored the reels of banned films that never got into cinemas, the room that had every movie we’d heard about but could never see, all six parts of Spiderman and all the Tarzan and Zorro films and a whole load of cowboy-and-Indian movies.

What the boys actually found wasn’t Zorro and Tarzan films, but reel after reel of pornographic films. Dragomán’s own experiences of censorship are equally bizarre.

“Usually in a society where there’s censorship, you don’t know what’s being censored. You have a feeling of what it might be, but you don’t know for sure. The best censors are always individuals themselves and the best censorship is self-censorship. We always had a feeling as to what was forbidden. It wasn’t as if there was a list of forbidden things, we had to guess just like Djata. The Hungarian minority language itself could be the object of censorship. I remember this one time [in the Socialist Republic of Romania] when a magazine was confiscated from me during a house search. It was the official magazine of the Hungarian communist youth movement, but it also contained semi-reformist stuff like articles about rock music and sex so that it would interest young people more, even though the main focus was on the communist party. Anyway, it was confiscated, which was surprising, it being a socialist magazine in a socialist country.”

The past and the exotic as fetishes

Naturally censorship only increases interest in the forbidden. In the chapter “The White King”, Djata steals a chess piece brought over from Africa. It becomes an amulet, something to help him find his courage and self-confidence. Its exotic, ivory surface would easily beat any tin soldier, no matter how exquisitely painted. Djata believes it will make him invincible in the boys’ war game. This is exactly the kind of fetishistic relationship to the past that emerges when a society is shut off from the rest of the world.

“I remember that there were no English books available when I started studying English. If I did well, my teacher would say “hush” and bring me old English newspapers. I knew that I couldn’t tell anyone, that this was a great gift. Then we’d read the newspapers from the 1960s, all yellow and worn out and study the vocabulary. Once the borders are closed, even everyday things turn into relics. You can find them in flea markets where you can see packets of tea from the West. Here we’d throw them away, we do throw them away, but there they became something almost magical, something people would collect. It kind of reminds me of a science fiction movie. In a way these events could be not from the past but from the post-apocalyptic future where signs of a lost civilization are collected as valuables.”

On the borderline between power and freedom

Dragoman has a very unambiguous relationship to power. There’s one position of power, however, that one can’t help but accept, as Dragoman was forced to realize. A dictatorship, but also something far less ominous – parenthood – is all about power.

“I am obsessive about power. I have never had a job or a boss, no employees and I don’t belong to any associations. I have always refused power as far as possible and tried to avoid it from both sides – both being in a position of power and a being the object of someone else’s power. It was a big deal in that way as well, then, when my children were born, since I knew I’d be in a position of power in relation to them. I have to be because that is what parenting is about. It didn’t feel very natural at first but in that situation you don’t have a choice. Maybe I’m not as strict of a father as I should be”, Dragoman ends with a laugh.

Freedom is always related to power, and like power, it can manifest itself in many ways. The White King is about power and freedom in a totalitarian regime, but questions of freedom are topical in democratic societies as well – or as Dragoman calls them, states without dictators.

“The concept of freedom is very interesting. Is even the thought of freedom possible in a society where freedom has been repressed to the point of non-existence? If I had some question I wanted to answer with The White King, it was this. Nowadays I often write stories that take place in Hungary or other free societies I know, but even then I observe the emergence of power structures.”

Though Dragoman and his family live in Hungary, he does not take a rosy view of the current state of affairs there. He uses the term “free society” if not sarcastically, then at least with a certain distance in his tone. He describes his own attitude as disillusioned, disappointed with the fact that the new regime didn’t live up to expectations. Dragoman says the old, wrong policies were allowed to continue, and returns to the theme of uncertainty.

“A major issue in Hungary is the fact that the old registers were never opened and therefore the era of secrets never ended. Now it’s too late, it’s been 25 years. It’s not even about trials, but about the right to know. The worst thing about living in a totalitarian system is the guessing game, never being sure of who the informants were. Now we’ve had a democratic system for 25 years but we still can’t be sure. We had a prime minister, who turned out to have been an officer for the secret service. We never had a cathartic confrontation with the past. This air of suspicion is in my point of view one of the reasons why the far Right have been able to gain power. Ironically they’re the only ones who are open in their rhetoric and goals”, Dragoman says with another of his dry laughs.

The author comments quite freely on the current political atmosphere. He explains his worries concerning the situation in eastern Europe.

“I don’t like the current situation at all. I don’t like the way Russia is going. After the change in regime all of us in Eastern Europe had a dream of catching up with the western democracies. Somehow that never happened, and almost none of the former Eastern Bloc countries evolved into an open society. My disappointment with politics has to do with the fact that the language of politics is the language of power and has remained that way in the former Eastern Bloc. Almost all of the politicians seek to use their power for personal gain, no matter what the party. In their time, the new regime created open election systems and principles of transparent rule, but these were quickly overridden. We were told we’d never have professional politicians again. I believed in this, but of course I was naive, only 15 or so. Soon a ruthless political system emerged, in which everyone was just trying to benefit themselves. Nominally the former Eastern Bloc countries are open societies, but the frame of mind of the people hasn’t changed and their relationship to power has remained the same. There aren’t enough independent institutions, politics seeks to own everything and dominate everything. The further east we go, the more the curious relationship to power manifests itself.”

Politics in text

The observation of power systems seems to permeate everything Dragoman says. It’s hardly surprising then that he sees his own poetics in the framework of power relations as well.

“For me, a story always begins as a short story. I’m very interested in how larger structures emerge from smaller structures. For The White King, I wrote a short story, then another and by the third one I noticed that it would be a novel, or maybe a short story collection. You can think of it as either, for me the difference isn’t so clear. I even have a collection of short stories that are made up of smaller short stories. Right now I’m working on a project that functions just so. It’ll be called “Shrapnel”, because that is what it resembles. This structure in which small units form large units that form even larger units suits me well.”

In The White King it is maybe because the narrator is a child that analysis of or reflection on what is witnessed seems to be absent. His perceptions of the world follow each other in an almost associative manner. The style also conforms to this feeling of constantly moving forward without the possibility of stopping; long paragraphs are made entirely of main clauses separated by commas. In “The Book of Destruction”, Dragoman’s first novel, the narrator is an exiled scientist and the aim was to capture a hyper-realistic view of the world, to see everything in ultra-high definition. With The White King, Dragoman had to try and un-see – forget the familiar way of seeing in order to connect with a child’s view of the world.

Using a child narrator was more than a stylistic choice, it, too, has to do with Dragoman’s ideas of power. Through a child’s eyes one may capture the brutality of living under a totalitarian regime without falling into explanations and historicity.

“I’m intrigued by the reader being able to assemble one story from several broken pieces of stories. I don’t believe in explanations. To explain is to use power and because of that I try to avoid it. When I started writing, one of the main questions was to do with reflection. The protagonist in my first novel doesn’t really think about what it is that he’s doing. I don’t want the power of creating a mind. I wanted to tell the story from the inside without reflection upon and the naming of events. The present tense narration I use in these works also has to do with the lack of reflectivity.”

Dragoman speaks of not thinking, the lack of thinking, although the process seems yield a different manner of thinking. The direction of thought is horizontal instead of vertical – a philosophical or analytical approach is replaced by observations and associative thinking that lack reflectivity.

My conversation with Dragoman finishes with his view of the relationship between thought and freedom:

“The way our society functions these days doesn’t encourage one to stop and think. This frenzy of doing things makes us forget to think. That’s why there isn’t time to think in The White King either.”