Hard labour

Many women’s experiences suggest obstetric violence is commonplace, from the overuse of caesarean sections to the risks of vaginal delivery. Putting women at the centre of decision-making about their own bodies ahead of ideological or financial medical priorities is imperative.

The creation stories that have informed Western culture are full of miraculous births, with gods and mortals emerging from heads, shells and spare ribs. Looking to the future, medical advancements in the realm of artificial wombs have meanwhile raised questions as to whether, by the end of the 21st century, humans will in fact be ‘born’ at all. For now, however, women still find themselves bound firmly to the earthly birth process – one that can be fraught with trauma or injury for mother and infant. Furthermore, the medical cultures and institutions that govern this process have historically undermined women’s agency, and evidence suggests that they continue to do so today.

Limestone statuette of a childbirth scene, ca. 310–30 B.C. The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76 via MET Museum, Public Domain

The innovations of medical intervention have greatly reduced maternal mortality across developed nations. In Finland, for example, they are as little as 5.6 per 100,000 live births, while rates across lower-income countries average at almost 500. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that nearly 95 percent of maternal deaths occur in low-resource settings and that most are preventable.

Given these advances and reductions in maternal mortality, modern medicine is often presented as the antidote to the risks of childbirth, taking control of the process to ensure a safer birth. These interventions range from caesarean sections – the surgical procedure whereby a baby is delivered through an incision in the mother’s abdomen – to the use of synthetic hormones to induce birth, epidurals for pain relief, and physical instruments such as forceps to physically pull the baby out. The fact that almost one third of female obstetricians in the UK (and almost half in the US) have expressed a preference for delivering their own babies via C-section may be enough to seed doubts about vaginal births among many women.

But at the same time, medical professionals and rights campaigners in wealthier nations are increasingly highlighting the obstetric violence – neglect, physical abuse or lack of respect – that too often accompanies medicalised interventions in birth. In this light, some maternity experts argue in favour of ‘natural’ birth, holding that we need to go back to basics, and retreat from medicalisation to rely on our human faculties and instincts.

The debate around birthing choices and the future trajectory of childbirth is a fraught and often polarising one, which can quickly veer away from evidence and into moralising and judgment. Many women find themselves at the mercy of the ideological or financial priorities of medical professionals and pressured into one form of birth or another, without the space to make their own informed decisions about their bodies. In this context, what does progress in the realm of birth really look like?

Obstetric violence

When Anna Michalaki returned home from the birth of her first child in an Athens hospital in 2010, she was traumatised. ‘It was extremely stressful,’ she says of her 34-hour labour. ‘I was afraid – I was treated with no respect by the staff and given no choice about what was done to me.’ It was only later that Anna, now a midwife, was able to name what she had suffered at the hands of the hospital system: obstetric violence. In 2018, she founded the Obstetric Violence Observatory in Greece to campaign to have this form of harm recognised under law.

Anna’s experience mirrors that of many women in a country with one of the most medicalised obstetric care systems in the world. The WHO recommends that caesareans should only be performed in cases of medical necessity. As it explains, this is surgery, and as such it can cause significant complications, disability or even death – particularly in settings that lack resources to ensure its safe execution. The WHO recommends a caesarean rate of around 10-15 percent. The average among EU member states is 25 percent. Reported rates in Greece, however, are well above half, with the real figure likely much higher. Anna says that some public hospitals she spoke to boasted of more than 90 percent C-section births. Following a 2016 review by the WHO, Greece pledged to reduce its excessive reliance on the procedure.

There can be financial incentives for doctors to perform C-sections, from limiting their overtime to payment perks for the surgery. This pattern has been observed in other high C-section countries such as Brazil, where there is a major spike in operations around Carnival, as doctors are loath to forgo the festivities while waiting around for a birth. These factors have been compounded in the aftermath of austerity in Greece. ‘Doctors don’t have good enough conditions to care about women’s health,’ Anna says. ‘Now the typical view is that the most important thing is that the baby is alive – they don’t care about anything beyond that.’ This pragmatism is coupled with what many have described as a chauvinistic and technocratic medical culture that is geared towards intervention at the expense of women’s choice and, often, their well-being.

‘You cannot question the doctor – they become something like a god,’ explains Anna. ‘They are preparing you for surgery through the whole birth process, even if you don’t know it. The messaging protocol is that you are sick – that your anatomy is wrong, so their method is to keep everything under control.’ Such an approach means over-emphasising the risks to mother and baby of vaginal birth, while undermining women’s own capacity for informed decision-making. Anna says that misinformation has created the widespread belief among mothers and their families that C-sections are a cleaner, safer mode of delivery. ‘Most women don’t know what a C-section is – they think it is an alternative to birth, not an emergency procedure. There is a cultural fear of pain and the woman often believes a C-section is better because her baby will not be stressed and she will not damaged. But if a woman is not properly informed, she cannot give informed consent.’

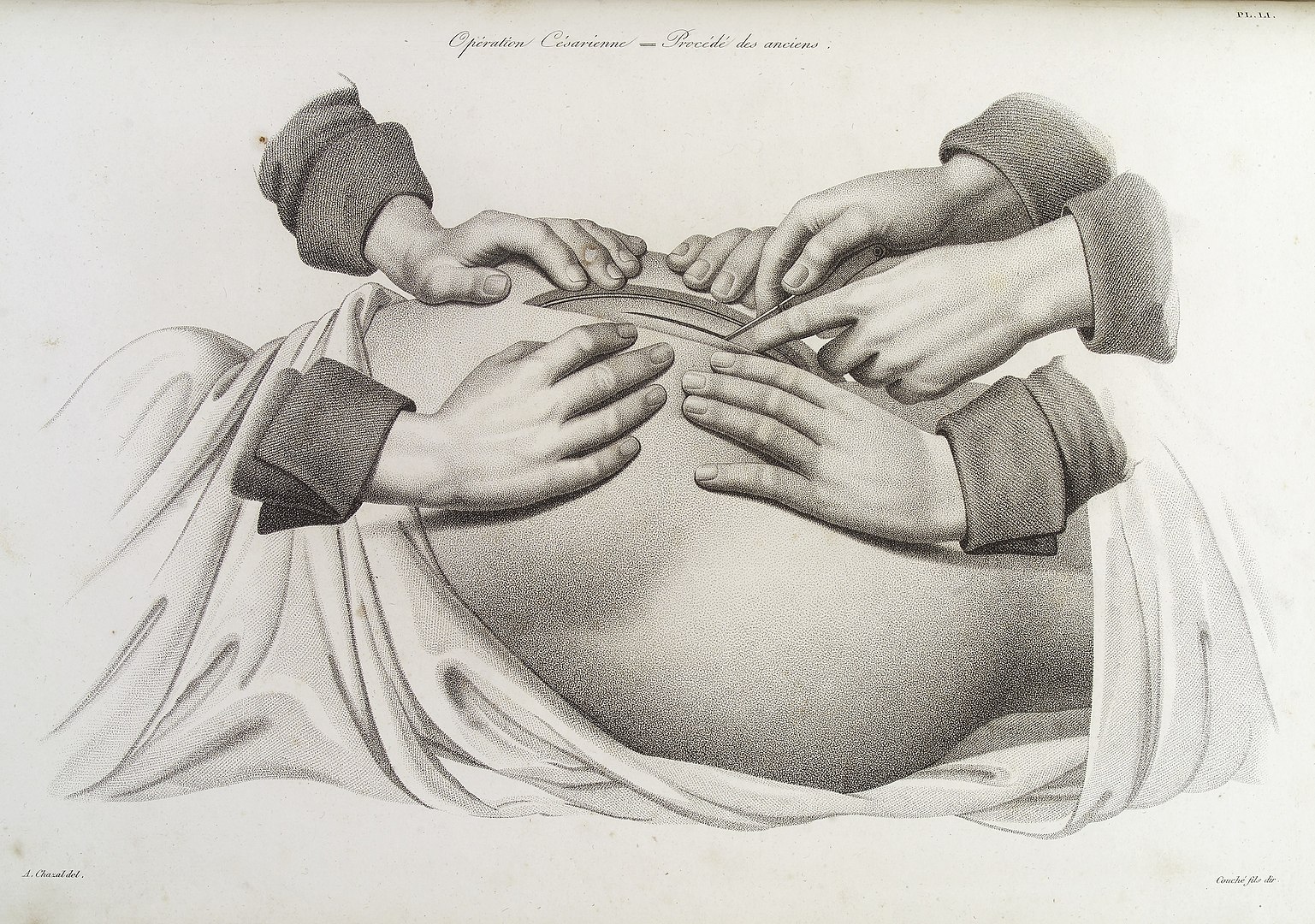

An early caesarean operation using a longitudinal incision. Image via Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons

One 17-year-old migrant mother who had a C-section birth in Greece’s largest public maternity hospital told me that she felt coerced into the surgery. ‘Before the birth, I was watching YouTube videos about C-sections and I knew that I really did not want one,’ she says. ‘But I don’t know what happened in the hospital – it was like I was not myself – I had no choice. The staff lied and told me I was seven centimetres dilated when I was actually ten and then I signed a paper agreeing to the C-section, though I was telling myself, ‘No, no, no.’ I felt so disappointed afterwards – I wish I could have been stronger.’

Similar observations about a medical culture that teaches women to distrust their own bodies have been made across developed countries. As one British midwife observed in a UK medical journal in relation to the notion of ‘choice’ around surgical deliveries, ‘[women] are convinced that vaginal birth will distort and mutilate their bodies and leave them gaping and incontinent, or they are simply frightened about what doctors will do to them, and believe that caesarean section offers the safest birth for the baby . . . They see vaginal birth as ugly, agonising – a form of torture – and enlist a surgeon to avoid this.’

‘Birth is seen as a problem’

This is not to say that new technology hasn’t improved outcomes. Giving birth is no longer the threat to life and health it once was, due to medical advancements. However, even beyond the potential for injustice or abuse in the deployment of such medical technology, some suggest that medicalisation has in fact diminished women’s natural abilities for childbirth.

Michel Odent has been a pioneer of natural birth since he founded the London-based Primal Health Research Centre in the 1980s. The French obstetrician argues that medical culture has conditioned us to regard birth as a problem, rather than a natural process. ‘The first question that is asked in medicine is, why is human birth so difficult?’ he says. ‘But instead, we should start from another question – why occasionally in the 21st century are there women who give birth easily and quickly without pharmacological assistance? That is – why can women give birth so easily? And if we start from this, we can better understand the basic needs.’

One of the most fundamental needs, Odent argues, is for a woman in labour to retreat from cognitive functions – and to be protected in doing so. ‘Giving birth is not a product of rational thinking – even today there are still women who can understand the solution that nature found, cutting herself off from her world, forgetting what she learned in books, forgetting her plans, behaving in a way that might be considered unacceptable in a civilised world – to scream and to swear, to find herself in postures that are mammalian or primitive.’

Yet the defining features of modern births – be it the presence of other people in the ward, unnatural lighting, machine monitoring or informational overload – all inhibit a woman’s inability to abandon cortical control and follow a more involuntary process. ‘In the 20th century, the history of childbirth was mostly influenced by technological advances – we had the plastic revolution, the electronic revolution, advances in surgical techniques and anaesthetics. These have been absorbed all over the world,’ says Odent. ‘But today, we have to de-programme the conditioning.’

From his early status as a leading voice on natural birth, encouraging the use of birthing pools and skin-to-skin contact after birth, Odent has become a more controversial figure following the publication of books such as Childbirth and the Future of Homo Sapiens and The Birth of Homo, the Marine Chimpanzee. These works argue that modern medicine is ‘neutralising’ the laws of natural selection by allowing babies to be born that might not otherwise have survived. While acknowledging the ‘miracle’ of modern medicine, Odent argues that its advent has meant that most women no longer need to use important physiological functions in order to have a baby – and indeed, that blind adherence to the medical trajectory may itself pose a grave threat to the future of human childbirth.

Foremost among his concerns is the role of oxytocin – the so-called ‘love hormone’ which is released during childbirth – whose levels have been decreasing over the past half-century due to the use of synthetic oxytocin to induce or speed up labour, C-sections and the actively managed third stage of labour. A reduction in birth-rates and shortened duration of breast-feeding in OECD countries also mean that the oxytocin system is underused among women and may as a result, he proposes, be weakening in humans overall: a development with far-reaching consequences beyond birth itself.

Odent notes that the first stage of labour is today much longer than it was in the mid-20th century. ‘We can anticipate that the capacity to give birth will become weaker in the future, taking into account what we are learning from epigenetics which shows that our physiological functions are underused . . . this is serious.’ These are provocative claims. But Odent does not discount the use of C-sections, maintaining that they are often preferable to a traumatic vaginal birth. The decision, as he acknowledges, is often an extremely complex one.

Damaging deliveries

A 38-year-old mother of two, Melissa still doesn’t know which birth caused her injuries. Both of the screenwriter’s sons were 4kg or more, both were born in London NHS hospitals and both times – once after a delivery involving an episiotomy and forceps and once after second-degree tearing – she was stitched up by the midwife in the room and sent home the following day. More than two years on, she suffers faecal incontinence as a result of what was later determined to be, among other injuries, a fourth-degree tear and prolapse. She is unable to have penetrative sex and has been instructed not to engage in vigorous physical activity in case it worsens her condition.

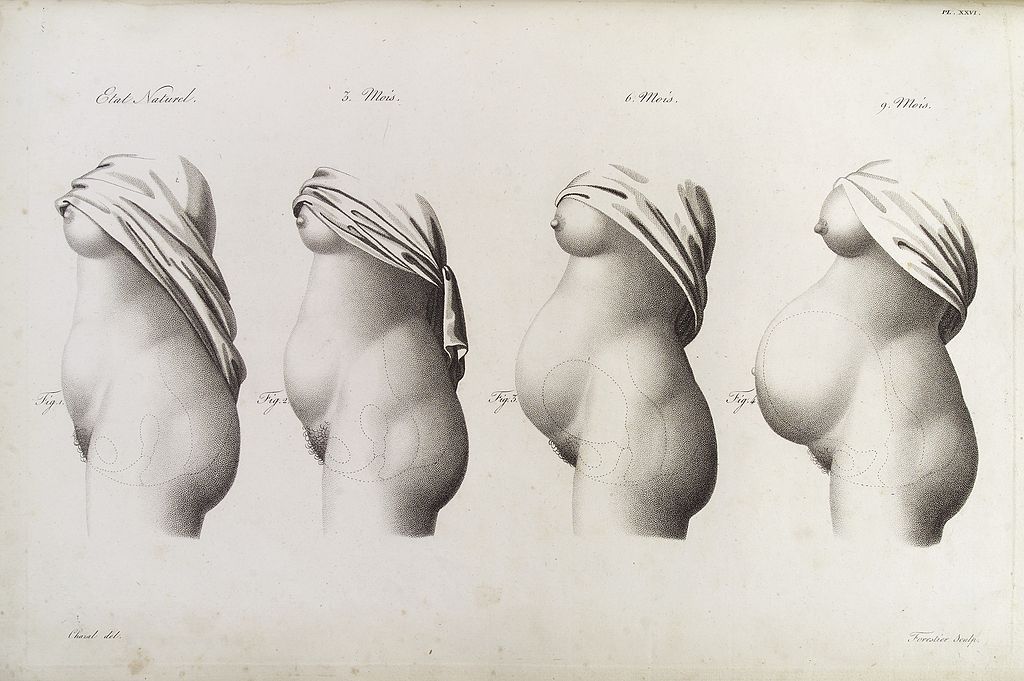

Stages in pregnancy as represented by the growth of the womb. Image via Wellcome Image via Wikimedia Commons

‘These injuries have had a profound impact on my life – I was left very depressed, suicidal and diagnosed with PTSD,’ she says. ‘I kept reliving the births, the decisions made that led to these injuries, my own ignorance of the risks, my naivety in trusting others. I’ve been left feeling disgusting, broken, ashamed, dirty, sexless.’ Melissa manages her symptoms – which she has been told will worsen with age – through various forms of therapy while she deliberates over the prospect of major and risky reconstructive surgery. Managing the social damage can be equally difficult. ‘I know women whose relationships broke down after their injury who have never sought another romantic partner, too ashamed of their symptoms,’ she says. ‘I know other women who’ve had to quit their job because the incontinence wasn’t possible to manage in their work environment, and those that don’t leave their homes because they’re afraid of having an incontinence episode in public.’

It wasn’t an outcome Melissa ever imagined when she first became pregnant. She attended all her maternity classes and midwife appointments, where – in contrast to Anna’s experiences in Greece – she was told about the dangers of interventions such as epidurals and C-sections and where natural births were emphasised as the preferred outcome for both mother and baby.

‘There was a lot of focus on how we didn’t want C-sections because they could leave you bed-bound for a week and the recovery was terrible and it would interfere with breastfeeding and bonding with the baby,’ she explains. ‘I was very scared of needing a C-section because I believed the information I was given. I was never given any information about the risk of vaginal childbirth, forceps delivery or what my choices were. I had complete trust in the healthcare professionals that everything would be fine.’

It was only through Googling her symptoms after the births that she learned about the prevalence of incontinence, prolapsed pelvic floor organs, chronic pain and sexual dysfunction from childbirth. The average woman in the UK faces at least a 10 percent risk of some form of post-partum incontinence – a rate which increases in births assisted with medical intervention, for example, forceps or episiotomies. Research from one UK study suggests that at least 9,000 women are left with life-long faecal incontinence from birth injuries every year.

In 2020, a major UK independent review of the use of specific medical interventions, the First Do No Harm report, concluded that women had been widely dismissed and disbelieved by medical practitioners when seeking help for their injuries – what some clinicians disregarded as ‘women’s issues’.

‘Women are exposed to injury, and at the mercy of a dysfunctional healthcare system that tells them that their injury is the cost of being a woman,’ says Melissa, noting that seeking diagnosis and treatment has cost her around £3,000 – a price that would be unaffordable to most women. ‘We tolerate the status quo in relation to birth injuries precisely because it happens to women. Caesarean section is considered the rich women’s alternative, for those who are ‘too posh to push’. That is a dangerous, misguided and vile assumption that undermines all women’s rights to body autonomy.’

Women are typically denied the necessary information to give informed consent to the risks of vaginal delivery, as Melissa sees it. ‘Obstetricians and midwives still adhere to a ‘natural is best’ ideology, prioritising vaginal delivery over other options,’ she says, noting the outcome of the independent 2020 Ockendon Review of NHS maternity services, which found that hundreds of women felt the pressure to have a ‘natural’ birth where a C-section might have been safer. ‘But what gives the ideology its lasting power is the economic reality – vaginal birth is the cheapest way to deliver babies. There is immense pressure for NHS Trusts to keep caesarean section rates down. Serious birth injuries are not rare, but the outcome of a system that cheapens women’s trauma because it’s cheap.’

Alongside greater information about the risks of childbirth, greater respect for women’s autonomy and improved aftercare, Melissa would like to see reforms implemented to restrict the use of instruments like forceps, as has been done in countries such as Denmark.

This article was first published in New Humanist Autumn 2021, reviewed by Eurozine 16/2021.

‘We need to be honest with women about the risks of childbirth. All childbirth delivery involves risk – [C-section] and vaginal birth. But it is women, and not an ideology about what is morally preferable or the financial imperative, who should decide how to manage those risks,’ she says. ‘Instead, we are treated as children, poor dears who shouldn’t be frightened with nasty stories that apparently only happen to a very small percentage of women. But birth injuries aren’t rare.’

The experiences of women in Greece pressured into C-sections, and women in the UK pushed towards a vaginal delivery, exist on a continuum. Rarer than damaging birth outcomes across the OECD, it seems, is any real engagement by the medical profession with expectant mothers as people with the capacity to decide what happens to their bodies and babies. Be it through interventionism, coercion or negligent omissions, women’s birthing experiences in the 21st century continue to be shaped by the ideologies, biases or financial imperatives of the dominant medical culture.

What can we do? Accurate, transparent and impartial advice from doctors and midwives is crucial; women cannot be expected to make such decisions unaided or uninformed. It seems the future here must be about pluralism, information, choice and equality. Babies were never dropped by storks, and the artificial womb is still a vision of the future. While women’s bodies are at risk in the birthing process, it is women who must be at the centre of decision-making.

Published 13 October 2021

Original in English

First published by New Humanist Autumn 2021

Contributed by New Humanist © Zoe Holman / New Humanist / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The imprisoned Belarusian opposition politician Maria Kalesnikava has been in a critical condition since the end of November. In October she was awarded an honorary professorship at the University of Salzburg. The philosopher Olga Shparaga, a fellow member of the exiled Coordination Council, pays tribute to a feminist legend.

While opportunities to denigrate one’s own physical appearance abound from an early age, eating disorders remain surrounded by stigma and lack an adequate vocabulary. From high school to pandemic isolation, a Romanian woman recounts eight years of grappling with anorexia.