Romania’s anti-vax movement has mutated into a pro-Russian protest bloc. Representing a politically disenchanted online public, the far-right Alliance for the Union of Romanians is increasingly influencing the mainstream agenda.

Social media extend the range of participatory acts open to citizens. The result can be unpredictable leaderless mobilizations involving massive numbers of small donations of time and effort. And although the vast majority fail absolutely, a few succeed dramatically.

Why did no-one predict the Arab Spring of 2011? And even in the years that followed, why does each new wave of mobilization, from the Occupy Movement to Brazil to Turkey, seem to take political commentators by surprise? The Internet and social media are fingered in all of these events, but far more attention is paid to (sometimes heated and occasionally pointless) debate as to whether these new media provide a greater boost to democratic participation or to authoritarian regimes (see Natalya Ryabinska in a

recent Eurozine article1). Meanwhile, across liberal democracies the political elite continues to bemoan the decline of politics and falling levels of civic and political engagement, particularly among the young, rendering themselves even more surprised by each new mobilization. Hence the need to better understand the characteristic of Internet-mediated communication that is making the difference to political mobilization and, to some extent, causing its unpredictability.

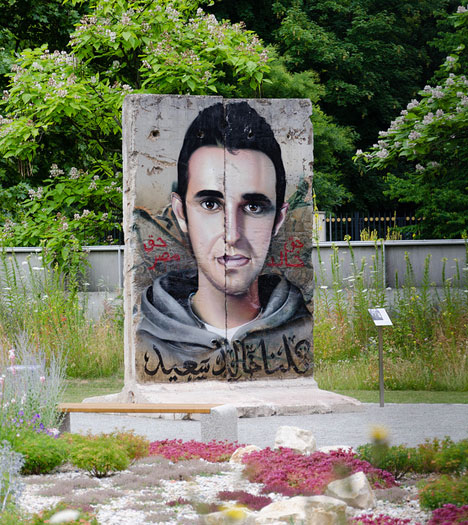

Memorial in Berlin for the Egyptian blogger Khaled Said. Photo: János Balázs. Source: Flickr

People in both democracies and authoritarian regimes spend growing proportions of their lives on social media. YouTube receives four billion views a day, Twitter has 140 million users while its Chinese equivalent, Sina Weibo, has 368 million users and Facebook has 600 million users. Half of US and UK adults use a social networking service. Even in countries with lower levels of Internet penetration, social networking sites have become popular, with Facebook the third most popular news source across Arab nations and 12 million users of Facebook in Egypt alone.2

These platforms reshape the context in which growing numbers of people decide whether or not to participate politically and change the cost-benefit equation of participation. They were mostly developed for social use, but they all have the potential to host a wide range of political activities, such as receiving and sharing news, information and views; expressing opinions; discussing issues; co-ordinating activities; and matching individuals across political, geographical and economic boundaries. And there is every sign that the swelling ranks of social media users are using these sites for political activities. In the US, data shows that 37 per cent of those taking part in social networking have used the sites to share political views, but among younger people (18-29) this rises to almost 50 per cent of US social network users, who say that they have used social media to discover their friends’ political interests or affiliations, to receive campaign information, to sign up as a “friend” of a candidate or to join or start a political group.3 The biennial Oxford Internet Survey (OxIS), the most comprehensive analysis of changes in Internet use in the UK since 2003, shows the rapid entry of new forms of participation in social media, such as contributing to a micro-blogging site (such as Twitter) or expressing a political opinion on a social networking site, which was carried out by 10 per cent of Internet users in 2013.4 In Arab countries, the proportions are higher; more than 60 per cent of users of social networking sites (around one third of citizens in Lebanon, Tunisia and Egypt) say that they use the sites to share views about politics and 70 per cent use them for community issues.5

In addition to general social media sites, there are now a huge range of Internet-based platforms dedicated to political activity, which may be regarded as social media in that they allow users to generate content through some kind of participatory act. Civic activism groups such as Avaaz and MoveOn operate sites where users can contribute a range of micro-donations of political resources quickly and easily, such as joining an email campaign or online protest, signing a petition or contributing money. Also worthy of note are the growing number of electronic petition sites operated by both governments and non-governmental organizations (including Avaaz), some of which now have a high profile within national contexts. In the UK, a petitions platform was operated by No. 10 Downing Street from 2006 to 2010, during which time it received over eight million signatures from five million unique e-mail addresses – a sizeable proportion of UK citizens. Other platforms facilitating political participation include JustGiving, a platform that allows individuals to set up their own donation pages for specific causes, which they then circulate to their own social networks. Elsewhere, sites run by the social enterprise MySociety make it easy for citizens to write to their political representatives (writetothem.com), find out what their representatives are doing (theyworkforyou.com), and complain about local infrastructure problems to their local council (fixmystreet.com). Similar sites run in many other European countries.

All these social media and campaigning platforms introduce new “micro-acts” of political participation, such as a status update on Facebook, a tweet or retweet, signing an electronic petition, sharing a political news item, posting a comment on a blog or discussion thread, making a micro-donation of funds to a political cause or campaign, uploading or sharing a political video on YouTube and so on. All these are very small acts of participation that for most people were not available until the advent of social media. In offering the opportunity to make these micro-donations of participation, social media reshape the context within which citizens operate, and influence their decisions about whether to participate politically. Such changes vary across the ever-increasing range of social media that have become available to citizens over the last decade: Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Weibo, Mixi, Cyworld, Orkut, as well as the dedicated civic activist platforms run by (for example) Avaaz, Kiva, MoveOn, MySociety and national electronic petition sites. Through their selection of which social media platforms to use and how long to spend there, individuals personalize the stream of information they receive, which in turn influences the scope and limitations of their political behaviour.

Social media extend the range of participatory acts open to citizens. Political participation denotes any activity undertaken by citizens with the aim of influencing public policy, for example through contributing to public goods such as environmental protection, cleaner streets, human rights, a more democratic regime, social welfare, better transport or security. Any individual deciding whether to participate will work out the benefits of the change and the probability of their action making a difference – and decide whether these benefits outweigh the costs.

There are some acts that uncontroversially count as political participation, such as voting or joining a political party. Most academic commentators perceive some kind of “ladder” of participation,6 ranging from small acts such as signing a petition, voting, attending political meetings or demonstrations, donating money to a political cause, protesting or demonstrating, right up to political violence and armed struggle. Use of social media across all spheres of political life means that some of these acts have moved largely to online settings, such as signing petitions, for example. Some remain largely offline, but are often co-ordinated through Internet-based means, including voting, demonstrations and political violence. Finally, some new acts enter the repertoire: posting a status, supporting or “liking” something on Facebook, Tumblr or Pinterest, tweeting or retweeting a political message, or disseminating a photograph or video of police or military violence on YouTube, Facebook or Twitter. All of which constitute very small or micro-acts of participation that add rungs to the bottom end of the ladder.

The new ease of micro-donation reshapes how people think about the costs of political participation. The cost is actually made up of two components. Firstly, there is the actual expenditure of time, effort or money involved in publicly expressing an opinion, making a financial donation or signing a petition, for example; or even, in some contexts, the risk of reputational damage if you cannot act anonymously. And, secondly, there are the transaction costs of the operation, which might include transport costs to the venue, writing and posting a cheque and acquiring information about the petition. Social media not only reduce the costs of participation, they also reduce the transaction costs both in absolute terms and as a proportion of the participation costs. Take a poster along the canal that asks passers by to contribute to a campaign to save Britain’s canals by sending a text message, which will automatically trigger a donation of three pounds sterling. Here the transaction costs, even for such a small donation, are very small, especially in comparison to sending the donation by post: the time to send the text message is probably less than locating the cheque book and addressing an envelope, and the cost of sending the text message is usually less than a postage stamp and possibly free in a bundle. In addition, the electronic transaction can happen immediately and avoid the mental effort of remembering the details on the poster. The cost of receiving the donation for the organization (the phone company takes just three pence) is also small in comparison to both the donation and the administrative costs of processing a cheque or telephone payment. Without such a mechanism, the transaction costs of sending the three pounds by post would have been much higher as a proportion of the donation; enough, indeed, to discourage the donation unless the prospective donor was willing to contribute more. Thus the mechanism for making the transaction facilitates a new sort of micro-donation. This lowering of transaction costs is accelerating all the time, even tending towards zero as potential participants receive requests for micro-donations of political resources in the course of their normal lives both online and offline.

It is not uncontroversial to describe these new micro-donations of time and effort as political participation. Many commentators think that participation primarily happens face-to-face or in closely allied activities, and that online activities are inevitably less important and peripheral. A “politics as pain” principle pervades much of mainstream political culture, which informs the view that contributing to politics should involve hard work and some kind of rite of passage. As a result, online participation is still often regarded as inferior to offline participation. This viewpoint was well encapsulated by the Chair of the UK Public Administration Select Committee in 1999, during a hearing on online political participation, at which I acted as an expert witness. In response to my suggestion that party supporters might use the Internet at home late in the evening to participate in party business, he replied:

If you describe it in that casual incidental way that gives a picture of people in a sense of having nothing better to do than to press buttons, not because they have anything in particular to contribute but because it is dead easy to do.7

In spite of all that has happened since these words were spoken, from the election of Barak Obama to the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement, it is clear that many in politics today share these sentiments when they hear about political activity taking place on Facebook or Twitter.

Similar views have led, from the early days of the Internet, to discussion of “slacktivism” (a conflation of the terms “slacker” and “activism”), a term to describe political acts that have little effect and that require minimum effort. The concept originally had positive connotations as a low cost small-scale route into political participation,8 but was later discussed in pejorative terms by a whole host of commentators, notably Eugeny Morozov in his 2011 book The Net Delusion9 and Malcolm Gladwell, whose notorious New Yorker article with the subtitle “Why the revolution won’t be tweeted” argued (shortly before the revolutions of the Arab Spring burst into public consciousness) that the small-scale actions and “weak ties” facilitated by social networking platforms such as Twitter could never engender the strong relationships that characterized the civil rights movement.10

Such views ignore how one small act – from which a person gains some measure (however small) of satisfaction – can lead to others, and also to larger acts of participation. The point is that when transaction costs sink so low, an individual who feels strongly about something is far more likely to do something about it as well. In a recent article in The Observer, the MIT political scientist Ethan Zuckerman argued strongly that “distaste for participation in dysfunctional political systems” evidenced, for example, by falling levels of voter turnout among younger groups should not be misread as apathy or a “crisis of civics”. Instead, Zuckerman insists that digital natives are participating in ways that they feel they can have an impact, citing online petitioning campaigns for sexual assault prevention and the “Dream” activism campaign calling for immigration reform carried out on YouTube.11 Such activities are made easily and cheaply possible by social media, crowdfunding and social entrepreneurship, in ways that would have incurred costs (in money, time and effort) far beyond the reach of their perpetrators 20 years ago, however passionately they might have felt.

The key point about these micro-donations, however, is that they scale up to something important and indeed, obviously political. Taken individually they may seem insignificant, but as we have seen in both democracies and authoritarian states, they can scale up to large-scale mobilizations and campaigns for policy change. While some would argue that signing an electronic petition is an insignificant political act, few would make the same claim of the petition against road-pricing in 2009 that obtained 1.8 million signatures and caused the government to reverse its policy. Registering a “like” on the “We are all Khalid Said” Facebook page during the Egyptian revolution would seem (at least after sufficient early “likes” ensured your anonymity) small, but once the page gained hundreds of thousands of supporters, it was able to play a key role in assembling the March of Millions in February 2011. Tiny acts of participation scale up to major mobilizations.

These mobilizations, consisting of massive numbers of small donations of time and effort, are qualitatively different from traditional, offline mobilizations. Early work on understanding how these mobilizations start up and gain momentum shows them to be prone to critical mass and tipping points, meaning that a (very) few of them succeed dramatically, while the vast majority fail absolutely. This makes them unstable and unpredictable. One key difference is the social information that social media platforms provide about the participation of others. When you sign a petition on the street, you know very little about how many other people have signed the petition. On a social media platform or petitioning site, you know immediately in real-time how many other people have “liked”, “viewed” or “shared” a political news item or video, or how many other people have signed a petition. In 2006, the then Yahoo research scientist Duncan J. Watts and his research team showed that the information provided to users of a music website about how many other people liked a song would influence how much that individual liked it. This phenomenon – where individuals on social media platforms are influenced by information about what other people are doing – can be used to understand the instability and unpredictability of cultural markets, where some songs become massively popular, while most do not.12 A similar effect can be observed in political markets, where individuals deciding whether to participate politically are influenced by how many other people have participated.13 This observation explains to some extent why the mobilizations that have characterized the last decade have caused so much surprise. Conventional institutions of politics, such as political parties and pressure groups are organizational actors about which we know quite a lot and whose behaviour we may be able to predict, but these are leaderless mobilizations with their own dynamic.14

As well as being a major sphere of political participation, social media provide a new way to research and understand it. Every participatory act, however small, carried out in social media leaves a digital imprint. So mobilizations produce digital trails that can be harvested by researchers to generate large-scale datasets, so-called “big data”. These real-time transactional data tell us what people are really doing or have done, as opposed to survey data that tells us what people think they did or might do in the future. It can be retrieved and analyzed with software, text and data-mining tools, and sophisticated network analysis.15 This is a new sort of data for social science, more like the data that characterize the hard sciences, offering huge possibilities for understanding individual behaviour. Typically such data represent some kind of whole population, making it possible to answer questions that analysis of partial and incomplete survey samples cannot.

Big data is the hottest new trend in the corporate world and has engendered a huge amount of interest from journalists, academic commentators and entrepreneurs.16 There is much debate over what exactly the term means, but typically it refers to data too large to be manipulated in a desktop computing environment and that has some of the characteristics (real-time, transactional, whole of population) outlined above. But despite the interest in big data, there have so far been few attempts to use it to further our understanding of government and political behaviour. Government has always collected records and produced outputs of its activities, but these have traditionally been dispersed into written forms, and even when kept on digital systems have tended to be the property of experts and professionals in the field. Now that data are more widely in electronic form – when governments are spending large amounts of resources to document and link up such electronic data sources, and when much of this information is now produced online – such data can be used to understand political processes and citizen interactions.

One example of such data that we have collected at the Oxford Internet Institute is a new big dataset of all the petitions created on the UK and US governments’ e-petition platforms over the last three years, as well as from a range of social media such as Facebook and Twitter, Google applications and the blogosphere, and website archives. Big data present a new challenge to social science in terms of the technical skills, multi-disciplinary expertise, ethical procedures and computing resources required to harvest, store and analyse it. But political science has never before had access to datasets like this, so meeting the challenge is certainly worthwhile.

So as well as contributing to the unpredictability of political participation, social media can provide a solution to understanding it and, perhaps, even to prediction. The new “political superstar” of big data, Nate Silver, shot to fame when his use of big data enabled him to predict the election results in all 51 states in the 2012 US presidential election. His otherwise excellent new book, The Signal and the Noise: The Art and Science of Prediction, discusses how various phenomena such as the financial crash of 2008, or the 2001 terrorist attacks were, were not or might have been predicted. But it does not discuss social media and political mobilization, or the Arab Spring or any of the above. Time, perhaps, to start applying the same methods to the even more messy and uncertain activity of political participation.

As a political scientist, I joined my peers in enjoying some jokes at economists’ expense over their inability to predict the financial crash of 2008. But post-2011, the joke has been on us. So I feel a sense of responsibility to make use of the massive potential that big data generated from social media provides to understand the changing face of contemporary political participation. My colleagues (Peter John, Scott Hale and Taha Yasseri) and I are developing a model to encapsulate the changes outlined above – we call it chaotic pluralism.17 Given that social media inject instability, unpredictability and even chaos into contemporary political life, it may be that scientific models of chaos theory in natural systems (characterized by non-linearity and a high degree of interconnectivity) can be applied in order to aid our understanding of a changed world.

Natalya Ryabinska, "New media and democracy

in post-Soviet countries", Eurozine, 9 October, 2013, www.eurozine.com/articles/2013-10-09-ryabinska-en.html

Dennis, E., Martin, J. and Wood, R., Media Use in the Middle East: An Eight-Nation Survey, Northwestern University in Quatar in association with Harris Interactive, 2013

Auer, M. R., "The Policy Sciences of Social Media", Policy Studies Journal 39, no. 4 (2011): 709-36, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1974080

William Dutton and Grant Blank, Cultures of the Internet: The Internet in Britain, Oxford Internet Survey 2013 Report, oxis.oii.ox.ac.uk/sites/oxis.oii.ox.ac.uk/files/content/files/publications/OxIS_2013.pdf

Pew 2012 Global Attitudes Project, www.pewglobal.org/2012/12/12/social-networking-popular-across-globe/

Verba, S., Scholzman, K. and Brady, H., Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics, Harvard University Press, 1995; Parry, G., Moyser, G. and Day, N., Political Participation and Democracy in Britain, Cambridge University Press, 1992

Margetts, H., "The Cyber Party", in Katz, R. and Crotty, W. (eds.), Handbook of Party Politics, Sage, 2006; Public Administration Select Committee, Innovations in Citizen Participation in Government: Minutes of Evidence, Tuesday 11 January 2000. In fact, when the same parliamentarian was presented with this quote at a seminar in May 2013, he nodded approvingly.

Christensen, H., "Political activities on the internet: Slacktivism or political participation by other means?", First Monday 16, no. 2 (7 February 2011), firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3336/2767

Morozov, E., The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom, Public Affairs, 2011, 1-409

Gladwell, M., "Small Change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted", The New Yorker, 4 October 2010, www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell

Zuckerman, E., "Political activism is as strong as ever, but now it's digital -- and passionate", The Observer, 13 October 2013, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/15/political-activism-on-digital-platform

Salganik, M., Dodds, P. and Watts, D., "Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market", Science 311, 5762 (10 February 2006): 854-6; Salganik, M. and Watts, D., "Web-based experiments for the study of collective social dynamics in cultural markets", Topics in Cognitive Science 1 (2009): 439-68

Margetts, H., John, P., Escher, T., and Reissfelder, S. (2011) 'Social information and political participation on the Internet: An experiment", European Political Science Review 3, no.3 (2009): 321; 344

Margetts, H. John, P. Hale, S. and Reissfelder, S., "Leadership without leaders: starters and followers in online collective action", Political Studies 61, no. 4 (2013)

See, for example, Hindman, M., The Myth of Digital Democracy, Princeton University Press, 2008; Gonzalez-Bailon, S., Borge-Holthoefer, J., Rivero, A. and Moreno, Y., "The Dynamics of Protest Recruitment through an Online Network", Scientific Reports 1 (2011): 197; Gonzalez-Bailon, S. and Barbera, P., "The Dynamics of Information Diffusion in the Turkish Protests", guest post at The Monkey Cage, 9 June 2013, themonkeycage.org/2013/06/09/30822; Aral, S. and Walker, D., "Creating social contagion through viral product design: A randomized trial of peer influence in networks", Management Science 57, no. 9 (2011); Goel, S., Watts, D. and Goldstein, D., "The structure of online diffusion networks", Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce, ACM, 2012, 623-38

Mayer Schoenberger, V. and Cukier, K., Big Data, John Murray, 2013

Margetts, H. John, P. Hale, S., Yasseri, T. Chaotic Pluralism: Social Media and Collective Action, forthcoming monograph.

Published 12 December 2013

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Helen Margetts / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Romania’s anti-vax movement has mutated into a pro-Russian protest bloc. Representing a politically disenchanted online public, the far-right Alliance for the Union of Romanians is increasingly influencing the mainstream agenda.

Although it makes for a great dramatic effect, the theories of the sudden death of democracy disregard the gradual erosion and capture of institutions, and the role of the populace – argues political scientist John Keane.