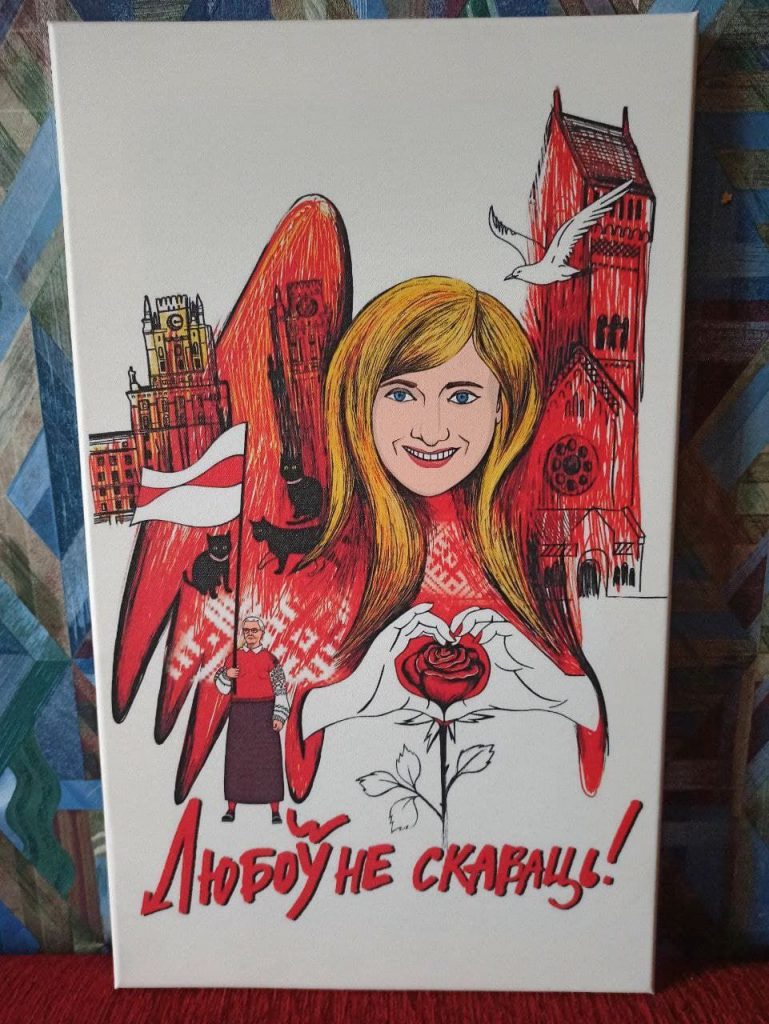

A former Belarusian political detainee reveals the remarkable depth of cohesion and trust between women activists confined for weeks in overcrowded prison cells.

Human rights organizations estimate that there are 605 political prisoners in Belarus.1 At least 71 of them are women, although unofficial sources suggest that the actual number of female political prisoners are over 100. Since 9 August 2020, 929 women have served a total of 13,0602 days imprisonment in conditions that can only be described as inhumane. This figure represents 30% of all registered cases of administrative arrest in the post-election period. The revolution in Belarus has not lost its womanly face.

Former male political prisoners I have talked to, or whose testimonies I read, also tell of how fellow inmates helped them deal with the appalling injustices they had to face from the Belarusian penal system. Solidarity does not recognize gender: both sisterhood and brotherhood have been features of post-election resistance in Belarus. Yet, in Eastern Europe, the stereotype that there can be no such thing as real friendship between women lingers on.

Thankfully, in the aftermath of the protests that began in August 2020, this misleading myth has been very effectively debunked. As a detained activist, I have experienced the genuine concord that can exist between women prisoners at first hand. When I asked a fellow inmate what helped her get through the prison experience recently, her response was unequivocal: ‘knowing that it was going to end… and the other girls, of course’.

September 8 detentions

Photo via onliner.by

So what’s it like being in prison?

The watershed was 8 September, the day on which mass detention of women by the security forces became a norm. My own administrative arrest in autumn 2020 lasted 9 days.3 Once you have been detained, you lose all sense of personal security. You may feel confident of having done nothing wrong; you may be certain that, whoever violated the Constitution, it wasn’t you. You may have a good understanding of law, and your legal representative may be superb, but none of this will help because people working for the penal system in Belarus function according to rules of their own.

Routine and unpredictability exist side by side. The daily schedule in prison runs as follows: 6:00 Wake-up | 6:30-8:00 Breakfast | 13:00-14:00 Lunch | 17:00-18:00 Dinner | 22:00 Bedtime. There are a couple of rollcalls during the day; a 15-minute walk maybe (we had one during the entire week); a shower perhaps – but not every day (we were lucky and were able to take one twice over the course of the week). As regards activities, the options are limited: books, games, a sport of some kind, singing or conversation.

But as soon as you start to feel more settled and emotionally secure, prison guards come and shuffle everything around. They take someone out and bring someone else into your cell. They order you to leave the cell with all your stuff, without clarifying what’s going on. They never explain. They don’t give clear answers to your questions. ‘Maybe…’ they say. ‘If you behave yourself…’ is also a favourite response. ‘If you ask nicely…’ is another.

There is no clock. You are caught in a timeless space. You may be able to guess the hour by the meals you’re given, or by the changing quality of light seeping through the window, if there is one. Sometimes a warden may take pity on you and tell you the time, but essentially you are at the mercy of another who has absolute power and control. They can do whatever they want. No one will stop them.

Life under administrative arrest

Since August 2020, prison conditions have changed for the worse. When I was serving my administrative arrest in Akrestsina and Zhodzina prisons in September, we received care packages prepared by volunteers, as well as by relatives or friends. There was a bunk for every inmate. We didn’t have to roll up our mattresses and we could sit or lie on our bunks all day. We were permitted to read for as long as we wanted, or play board games which could be included in care packages. At 10pm, the bright day lights were turned off and replaced by dim night lights.

Akrestsina Detention Centre Photo by Hanna Komar

Gradually, it got worse. It was common for those held by a district police department in Minsk to be brought to Akrestsina prison, where a trial would take place on Skype. In October, it was announced that care packages could be received in Akrestsina only once a week, on Thursdays. The epidemiological situation was cited by way of justification. In a prison located in the town of Zhodzina, parcels arrived on a Wednesday. In the prison in Baranavichy, where those detained during marches and rallies were moved, care packages could only be delivered on a Tuesday. Very often, prisoners from Akrestsina would be transported elsewhere overnight, between Wednesday and Thursday, which meant they’d have to wait an extra week to receive items they badly needed. For girls this included basic toiletries such as sanitary pads or tampons.4

In January 2021 the prison in Zhodzina stopped accepting care packages5 sent to those arrested on political charges. The same also happened in Akrestsina, and the ruling lasted until mid-February. There have been a lot of issues with parcels, particularly in recent months. You can bring one in and they may accept it, but only part of the contents is likely to reach the inmate, or it may be handed over to her only when she’s released.

In January 2021, following the cancellation of the Ice Hockey Championships in Minsk for reasons of ‘safety and security’, they began putting up to four times as many people in a cell as there were bunks – probably by way of punishing protesters. Every day, a bucket of water with a high concentration of chlorine was poured onto the floor of each small cell.6 Even now, more than six months on, all mattresses are taken away, windows aren’t opened, and there’s often a lack of air in cells. Political prisoners have to share cells with homeless people, and are left to deal with the lice, the smell and the soiling which goes with that. Nonetheless, protests have continued and consequently people are still being detained.

Tending and befriending

In the cells, women call each other ‘sisters’.7 Mutual support is all women have to help them through administrative arrest, which lasts between 10 and 30 days. Sisterhood of the kind I experienced with the other girls in prison was, to me, neither new nor surprising. I have been in activism for about 10 years. The communities I have been part of live by principles of mutual respect, non-violence, sharing, caring and creativity. Many of the women most actively involved in the resistance have been through at least one detention. Some have been detained four, five or six times. But, for many, these principles – which we applied on a daily basis – proved a revelation and an insight, something they hadn’t imagined could be possible.

Prior to the human solidarity chains, the marches and other protests which began in August 2020, for most Belarusian women friendship had been about hanging out, having fun and sharing experiences. But being a revolutionary, a fighter, proved very different from anything they had known before. Many women found they were the only ones in their small communities actively involved in the protests. At best, they could rely on their families. At worst, they were completely alone.

‘I think we had all got used to relying only on ourselves. It’s not just that we didn’t count on anyone’s support, we were wholly prepared to withstand things alone.’ Katsia, detained three times (on the last two occasions, she served 25 and 30 days of administrative arrest).

For me, the most striking thing about prison was how quickly we got close to the other girls in our cell. We’d met just the day before but we were soon sharing some of the most intimate details of our lives, as though we were old school friends or sisters. Yes, sisters. It wasn’t just girly chat or the sort of thing you might tell someone on a train, it was a form of meaningful therapy.

Photo by Hanna Komar

Under normal circumstances, it takes far longer to reach the depth of insight we managed to achieve in just a few days. The level of trust was immense. Was it because we shared the same political stance, the same conceptual framework? After all, ideas do bring people together. Or was it because it was an extreme situation, that wasn’t planned or controlled by reason? Was it because our intuition had been so sharpened by circumstances that we could now step around each other’s feelings with our eyes closed, like cats on their soft paws?

According to research on Biobehavioural Responses to Stress in Females at the University of California, females create, maintain, and utilize social groups built on attachment and caregiving to manage stressful conditions. Evolutionary psychology refers to this as the ‘tend-and-befriend’ pattern.8

‘You get there and you find your tribe. People are strangers to each other, but there is support. One girl weeps, another gives her a handkerchief. You feel sad, they support you. You have no socks, they give you socks. No panties, someone has an extra pair. There’ll be a kind word, a joke, an anecdote – it’s all support, and it’s real.’ Liubou, 4 detentions and 2 administrative arrests (10 and 15 days).

As far as we could, we stayed positive – at least on the outside. We all knew that our moods affected the others. We knew that once you let your mood dip it was hard to restore it and that there was no point being negative. We turned imprisonment into a summer camp. In prison, women from the resistance movement sing songs, read aloud, play games, draw and come up with creative activities so as not to drown in that sticky lump of timelessness and powerlessness. In her head, each and every one of us has a clock and a calendar. We count every second we spend in captivity – but never aloud.

Beyond the prison walls

There was also the remarkable support that unrolled for me afterwards, on my release. September 2020 was only the beginning of what turned out to be a marathon and, like so many of us, I had to learn from scratch. Now I know exactly what to do when someone is detained because there hasn’t been a month when at least one of my female friends hasn’t ended up in prison. They have kept on fighting despite the daily danger and terror.

When a sister is detained, there is an algorithm to be followed. Remove her from your chat, call her relatives, telephone the lawyer, find the video footage from the place of detention, prepare a care package, monitor current court proceedings so as not to miss her trial, be present at the trial, send the care package, share information if needed, write letters, prepare to greet her when she comes out, meet her on her release from prison, bathe her in love and care. When you’re the one in trouble, having backup of this kind helps you through. It is also a form of self-preservation.

‘You know that, at your trial, you can’t be soft. You can’t look bad, you need to get your shit together because other girls will be there, as well as that lawyer who admires us for our strength and courage. You know those people are there, on the other side of the screen, and that the lawyer’s task is mainly to connect you with the outside world – it’s important not to allow things to be hidden.’ Katsia

On several occasions, thanks to footage we got from places of detention, the lawyer managed to prove there had been no disobedience. Consequently, charges for that had to be withdrawn which meant that some girls received 15 days of administrative arrest instead of 30.

Many girls I have kept in touch with have been detained more than once. But it didn’t break them. Quite the opposite. I can see them becoming even more persistent in their aims and their fight for justice. One major reason, I believe, is that they are part of a community of women who give one other absolute support.

Photographer and camerawoman Tanya Kapitonava was detained in May 2021 on allegations of participating in an unauthorized mass event. A group of women in white clothes had laid flowers by the Kamarouka market in Minsk in the memory of the first solidarity chain which took place on 12 August 2020. Two weeks after her release from a 10-day term in Akrestsina prison, Tanya wrote on her Facebook page:9

I don’t like it when they say that you aren’t a true Belarusian unless you’ve been in prison. I don’t believe that this kind of experience determines your identity. I see Belarusians as people who are free and strong, not as prisoners. But here’s what I’d like to say to those who live in anxious anticipation of detention: if it does happen, afterwards you’ll be embraced in such a wave of love, attention and care that you are certain to cope with the trauma. I hugely appreciate everyone who supports me and I will remember this time as one of the strangest but happiest periods of my life.

Unconditional sisterhood

A similar kind of solidarity holds for political prisoners tried on criminal charges. Katsiaryna Barysevich10 is a TUT.BY reporter who spent 6 months in a penal colony for an article that challenged the official version of the death of artist Raman Bandarenka. Her report cited a medical document proving that Bandarenka had no alcohol in his blood and that he had died from severe physical injuries. Barysevich described, in an interview with Belsat,11 how prisoners value receiving letters and how prison inmates made handmade cards for feast days and festivals to cheer up those who hadn’t received letters. She recalled dancing in a cell with journalist Katsiaryna Andreyeva12 and Volha Filatchankava13, professor at the Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics.14 In her letters home, Katsiaryna included beautiful cards drawn by Ala Sharko15, programme director of the Belarus Press-Club. At one point they spoke six languages in their cell. ‘We imagined gathering in a hostel in Latin America and telling stories in different languages,’ Barysevich said.

Protest in memory of activist Witold Ashurak in May 2021. Protesters show the Tut.by logo. Photo by Паўлюк Шапецька via Wikimedia Commons.

There are three days in this brief account of life in Akrestsina prison, which I must highlight in particular. According to data released by the Human Rights Centre ‘Viasna’16, more than 3,000 citizens were detained on the night of 9 August. Over the course of three nights, 9-11 August 2020, the number soared to about 6,000. Akrestsina prison effectively became a concentration camp17, and those held included women.

Maryna was detained on 10 August and released four days later. She told me there were 20 people in their cell at first, but then 33 girls from the cell next door were transferred into theirs. This was a cell designed for 4 inmates. To free up some space, things had to be rearranged. Maryna told a girl who had a wounded foot to move to an upper bunk, so her foot wasn’t stepped on. There were five girls on each of the lower bunks but only four sat on the upper bunks, because everyone was concerned that they might collapse. Those on upper bunks collected and stored hoodies and other clothes which took up space below, even though it made the space around them even more scarce and they were sweating heavily in the heat.

Women stood on the floor, they sat on the table and under it, anywhere there was room. They had a roll call to check if anyone needed help, or had injuries and needed to sit. The cell was buzzing. Your head felt like it was going to explode and you wanted to blame the others but you remembered that it wasn’t they who should be blamed, not these fragile kind-hearted girls. There were older women too. Some had been injured and beaten. It was very hot, there was practically no air, you were nearly fainting, and a single bottle of yellowish water was passed around. The nightmare lasted for hours and hours and hours.

For Maryna, the most touching thing was that the women released before her had memorized her mother’s phone number and called to say Maryna was alive, and to give a few details about her and the situation in general. They had basically just emerged from what felt like a gas chamber, but they found the strength to contact the family of someone who was still in there. To Maryna, this seemed like a miracle. I’d call it the wonder of solidarity.

Support of this kind comes mostly from those imprisoned on political charges.18 Women under administrative arrest for alcohol abuse, misdemeanours at work, or facing criminal charges for murder, theft or avoiding child support payments, were generally either calm and passive, or viciously aggressive with a tendency to provoke conflict where there had been none. But, at times, even they joined the sisterhood to sing. And as the changing behaviour of women like Katsiaryna Barysevich and Volha Khizhynkova proved, if you treated them with respect and kindness, they too softened.

Photo by Hanna Komar

A new kind of family

It began with human ‘solidarity chains’ made up of strangers protesting against police brutality. Today, it is a family and more. The women I interviewed had never imagined such support to be possible. Now they believe that, once it’s all over and we are able to go back to our normal lives, they will stay active and in the network.

I hope this example of solidarity can be shared. I look forward to seeing it seep through into communities and entire countries filling people with a love and care stronger than any prison wall. I hope it will inspire millions to become better versions of themselves. I hope it might change the world.

Figures from 3 August 2021: https://prisoners.spring96.org/en

The author was held under administrative arrest 9-17 September 2020. Her experience is also the topic of a book currently in preparation.

According to the Human Rights Centre ‘Viasna’, there are currently 71 women political prisoners and 32 former women political prisoners in Belarus.

Published 9 August 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Hanna Komar / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

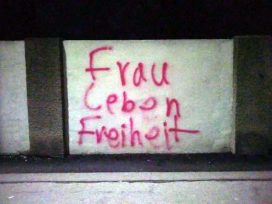

Women’s rights activists protesting for a democratic Iran counteract armed police on the streets with non-hierarchical leadership, a rhizomatic network, transnationality and flash mobs. Their momentum, supported globally via the Iranian diaspora, also benefits from a legacy of historic feminist action under extreme oppression.

Revolution in progress

Voices of Belarusians in exile

The Belarus Revolution started in 2020 after a rigged presidential election. It ended, at least to outward appearances, with Lukashenka’s brutal repression and stricter outlawing of future protests. But, for many, the struggle continues: a new study on protestors’ recollections refutes the perception that the revolution failed.