As a patient who’s recovered – on paper – from a severe eating disorder, my first thought as I start my Cipralex treatment is that I’m highly looking forward to the nausea. Cipralex is an antidepressant I previously took as a teenager and to which I return, as nearly one whole year of the pandemic spent alone, with just the cat by my side, has brought me to my wits’ end.

In the first month, which is how long the body takes to adjust to the treatment, the only thing my stomach can hold down is toast or roasted eggplant spread. Yet the joy of waking up with flat abs overpowers the discomfort caused by nausea and hunger and, after many years of obsessively focusing on what and how I eat, the old sensation of control gets reactivated.

My problematic relationship with my own body and food starts in high school. I’m 16 years old and it will take me a bit less than two years to be diagnosed with an eating disorder. I work out regularly and my motivation for walking through knee-high snow to the newly opened neighborhood gym is a new and unexpected feeling. I feel powerful. I’m thinking I only have to lose a few kilos to feel more at peace with myself, less insecure. At night, with the next workout on my mind, I save countless pictures tagged #thinspiration on Tumblr. My phone is full of them.

One year later, my family and friends compliment me when I return home from a summer course at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, in Wisconsin, thinner than when I left. Everyone seems proud that I managed not to gain weight in America, of all places, where it’s brimming with temptations and junk food. I spent my time in Milwaukee drawing all summer long and felt good, not just because I love to draw, but because if I have something to keep me busy it’s easier to skip meals. I’d walk for half an hour to the closest Trader Joe’s and buy zero fat cottage cheese and bagfuls of celery, then I’d obsessively look at myself naked in the dorm room mirror, trying to figure out how I could squeeze some more kilos out of this body.

I got a running buddy, but it bugged me that I couldn’t tell whether or not I was thinner than her. I made up fun new little games to play with myself: ‘Let’s figure out who’s thinner than me when I walk into a room full of strangers,’ or ‘Let’s find the most low-calorie meal on today’s cafeteria menu.’

Once I got home, to Bucharest, neither I nor those close to me had the vocabulary to ask questions about my new habits. For others, I was a former fat kid losing weight in a healthy way, eating balanced meals, who had spent her summer becoming a better runner down the Milwaukee River. My parents were starting to think I’d lost enough weight and slowly began worrying about my excessive zealousness with sports, but not even they could’ve suspected the mental mechanisms that were dragging me deeper into anorexia.

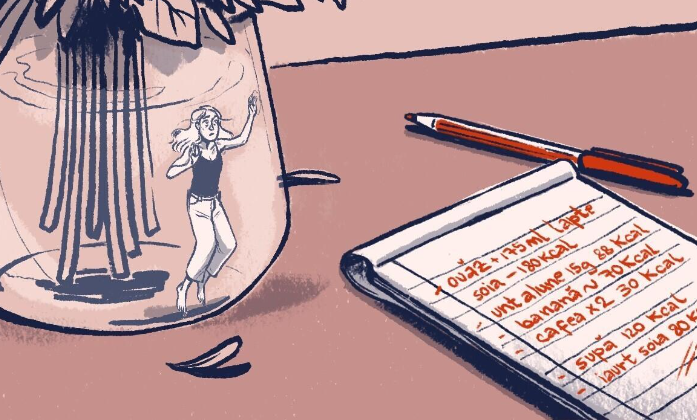

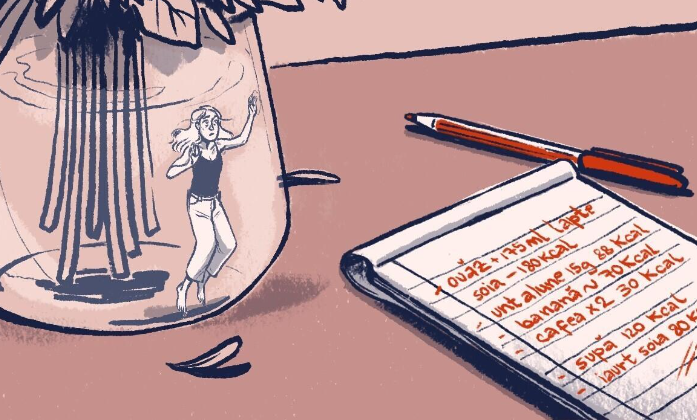

I’m 18, in my senior year of high school in London. I wake up to oatmeal and soy milk, 180kcal, 15g peanut butter, 88kcal, a medium-sized banana, 80kcal – maybe 70, ‘cause it’s on the greenish side. For someone my age, the daily necessary calories to get all the nutrients I need and have enough energy is around 1,600, maybe even 2,000, but I play this game with myself, where I eat no more than half that, maybe even less.

Lunch stresses me out because I can only estimate what’s on my plate. I tear up with frustration when the cafeteria lady serves me my steak smeared in the oil on the baking sheet. If no one’s watching, I wipe it with paper tissues or at least poke the steak around on my plate, to get rid of the excess fat, until it’s completely harmless. After all, the high school building is tiny and so are the toilets, too crammed together to purge a meal I consider dangerous. And by the time I get home, I digest that violent amount of calories anyway. The potatoes! Oil splashed before my very eyes, with diffident negligence, onto the salad that becomes untouchable. Please, don’t ask me if I want bread with that, my ears are already ringing.

Sometimes, when cafeteria food becomes too stressful, I go out to the supermarket next door to the school, which I pace up and down, aisle by aisle, compulsively reading labels, in search of something low enough in calories. I usually don’t find anything I’m happy with and wind up being late for class, too.

I realize something’s wrong. I was the one who decided to move to England, because I was depressed. But instead of feeling better, I’m feeling worse. So I decide to start therapy. I have Skype sessions with a Bucharest-based therapist and on my first session I tell her everything in a frenzy, hoping an abundance of details will help her understand. ‘So I need you to help me get rid of the depression,’ I tell her in the end. ‘I think that, if you’d like, we’d be better off working on your eating disorder,’ she replies.

The diagnosis floors me. I was sure this behaviour was a symptom of depression and, although ever since I started living alone I’ve religiously performed compulsive rituals centered around food, it has never before crossed my mind that they might be something other than forms of sadness.

Yet what the therapist says somehow calms me down. So there is a resolution out there somewhere.

illustration by Simina Popescu.

Eating disorders are mental afflictions that alter one’s perception of the body and relationship with food: these become the main concern, on which most thoughts and habits are centered. An anorexic person, for instance, is deeply afraid of putting on weight and starts having a distorted image of what they look like. This way, they can end up losing a lot of weight in an unhealthy manner.

Bulimia, on the other hand, comes under the guise of frequent episodes of compulsive consumption of abnormally large quantities of food, within a short time span. The sensation of losing control is followed by restrictive activities (vomiting, laxatives, excessive physical activity). Binge eating disorder, which involves compulsive eating, is similar to bulimia, but lacks its compensating behaviours. Since, most of the time, eating disorders function on a spectrum, there are cases in which the symptoms don’t strictly fall under anorexia or bulimia, but they need to be taken just as seriously.

Isolation during the pandemic has created conditions that make eating disorders thrive. No one knows exactly what’s going on, how much longer it will take, and how great the danger is. Pleasurable activities are increasingly less accessible, so, out of anxiety or the need to control at least one aspect of all this uncertainty, you focus on your own body and food. If before the pandemic I could walk around the city, do yoga, boxing, ballet, or swim, and was trying to keep my self-destructive impulses in check, in lockdown I slide toward stress eating and sedentariness.

Too many mixed feelings caused by the general uncertainty and the mental chaos of working from home do away with any and all motivation I had to work out. On social media, pictures of what people are cooking while self-isolating (a reminder to myself that the fridge is nearby), influencers telling us not to gain weight (a reminder that I have to fear this possibility), Zoom sports classes (a reminder that I ought to be productive). If your relationship with your own body and food is tense, this is just about the worst scenario, in which it’s harder than ever to avoid the triggers of eating disorder-specific thoughts.

During the pandemic, an increasing number of people have developed such disorders. Others, who, like me, have dealt with this in the past, relapsed against the backdrop of collective panic. In Romania, we don’t have data on the number of eating disorder patients, or any recent spike in cases, because the problem isn’t really being researched, taken into account by doctors, or brought into the public conversation too often.

The site of the National Association for Preventing and Treating Eating Disorders, for instance, last posted to the ‘Scientific research and news’ in March 2013. In the United States, however, the number of people to call the National Eating Disorders Association hotline increased by 78% from the spring of 2020 onward; by July of the same year, 62% of all anorexic patients in the US reported worsening symptoms from the beginning of the pandemic. England also saw a massive increase in anorexia and bulimia case numbers and, in February 2021, when pandemic-imposed restrictions became more drastic, doctors expected a ‘tsunami of patients.’

Despite what you see in the movies, even though young people are, indeed, more vulnerable, owing to the changes brought on by puberty and social pressure, it’s not just teenagers or extremely thin people who develop eating disorders. They can appear in people of any age, gender, or size. The stigma and social perceptions around obesity make diagnosing overweight people difficult and men are far less likely to seek help when they notice symptoms, because of gender stereotypes. However, in the United States alone, ten million men will suffer from an eating disorder at some point in their lives.

Yet this is not the only reason why these disorders are hard to identify. Above everything else, there’s an acute lack of information – we don’t learn about such disorders in school, they are very rarely mentioned in the press, and the few representations they receive in the movies and on TV are rather stereotypical and superficial. Then, magazines, TV series, shows, and the fashion industry still maintain some inflexible beauty standards (for both men and women), which are nearly impossible to reach and subtly dominate our screens and self-perception.

In Romania, where the conversation on mental health took off late and is going slowly, we’re not taught about the foreboding signs of an eating disorder and the symptoms we should worry about, whether we notice them in ourselves or someone close. We live in a society in which one of the most dangerous classes of mental disorders is given a worryingly small amount of attention.

Even the diagnosis given to me by my therapist was shrouded in taboo and scared me at first, because of that very lack of information. Never had it crossed my mind that the habits I was forming were symptoms of a mental affliction. And it didn’t seem to me I hated my body more than any other girl I knew. It seemed – it still does – that all the women around me have countless terms in their vocabulary to denigrate their own bodies. The body, which is never toned, light, narrow, summer-ready enough. And the conversations on how we can obtain an ‘adequate’ body are ever-present, from when we reach puberty, throughout teenagehood, and in our lives as adult women.

Illustration by Simina Popescu.

The therapy sessions I’m taking, laptop in my arms, in my London dorm room, don’t manage to change the fact that I feel alienated and alone, so I take deeper shelter in my obsession for weight loss. I can’t control the behaviours of those around me, who are distant and have already formed groups of friends, and I don’t have the emotional tools to handle the situation.

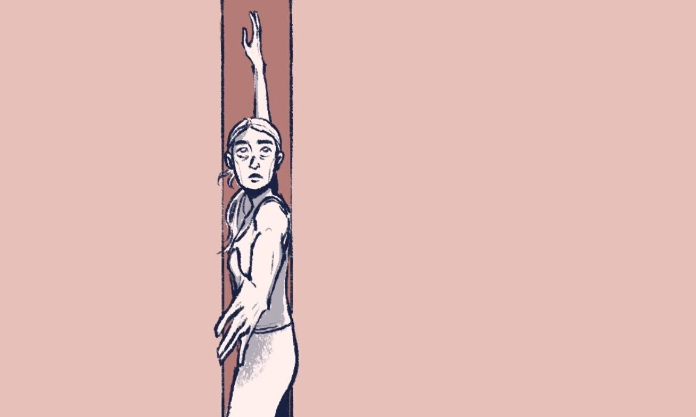

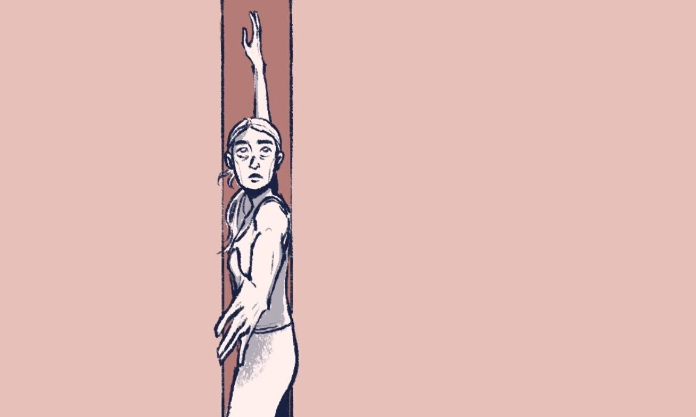

But I can control my own body. I lug my yoga mat to each class, bumping into the other students, to whom I don’t talk out of a fear of rejection, and run off right as class is over, so that I don’t miss the daily yoga class in a room that’s been heated to 40 degrees centigrade. In the triangle pose, trikonasana, the instructor guides us to visualize our body between two glass walls. I like to imagine myself as a pressed sheet of paper, until I disappear completely.

I sometimes take the bus instead of walking the four kilometres from high school to the dorms, but feel guilty and disappointed in myself all the way back. I’m always tired, I’m hungry, and have barely made any friends. Two months after the beginning of the school year, when I come home to Bucharest, my mom passes me by at the airport and doesn’t recognize me: I’ve lost 9 kilos since she’s last seen me. She’s scared by the way I look, but I see it as a victory. At least I can do one thing right.

I meet my friends, who try to tell me I look unhealthy, but I look them in the eye as I tell them about the high school in England, the city, the people – to distract them from the fact that I’m removing the excess flatbread from the wrap I ordered with surgical precision. White flour, carbs, probably 300kcal!

From the materials I receive in therapy I learn with great interest about eating disorders and my own behaviour, which actually doesn’t fall under anorexia or bulimia, but is somewhere in between. But I obstinately refuse any initiatives that might change my habits. An anorexic patient’s greatest fear is to gain weight.

The therapist suggests I write down everything I eat in one day, probably to show me that I eat extremely little, with poor nutrition, and that I’m allowed to be less restrictive. It doesn’t produce the desired effect – instead, I become addicted to the feeling of control that comes with documenting my daily meals. I’ve never been the kind of person who keeps a diary, but, from then on, the next years of my life are marked in the notes on my phone, on endless lists of absolutely everything I eat. I add calories with an enthusiasm that’s uncharacteristic of someone whose last maths class was in the eighth grade.

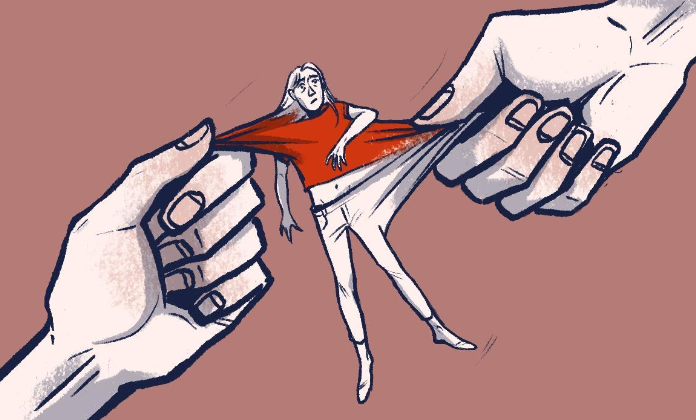

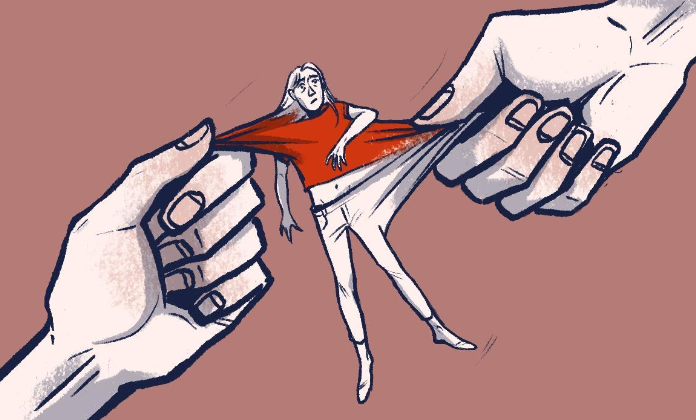

At the core of eating disorders lies distorted self-perception, the conviction that there’s something wrong with your body, accompanied by feelings of guilt, uncertainty, or anxiety. The obsessive-compulsive component of eating disorders gives rise to the symptoms, which manifest as food-centric rituals. There’s a need that’s hard to appease, that you need to eat correctly – perfectly, even. Yet this doesn’t mean correcting your dysfunctional relationship with food, but bringing the dysfunction to perfection, in a way which, seen from outside the sufferer, can seem completely illogical.

You start developing all sorts of behaviours that help you cope with the thoughts and feelings around your own weight: you eat less and less, avoid certain food groups or eating in public, work out excessively, throw up, or take laxatives whenever you feel you’ve eaten too much. You practice all these habits with increasing inflexibility and as self-punishment, without breaks or exceptions.

I’ve been ashamed of the way I look ever since I can remember. I can’t exactly tell when this feeling of inadequacy started. As a child, I grew up in a competitive and conformist environment and, everywhere I looked, I saw a single way of looking good as a girl, a woman. It was also painfully clear to me that I didn’t fit that mould. There were clear rules on what you should look like in the comic books I read in primary school and in teenage magazines – thin girls, who wear skirts and dresses, put on make-up and talk about boys, or have a boyfriend. I was chubby, wore glasses and didn’t feel like my clothes were trendy. The first time I felt attracted to a boy was in high school.

While I’ve been complexed by my weight ever since, Maria, my best friend during our first years in school, was affected by the fact that she was the only little girl in our class with a very short, ‘boyish’ haircut. Maria grew into a person who pays a lot of attention to the clothes and make-up she puts on, to maintaining a feminine look, so that no one ever mistakes her for a boy again.

I look at photos of the two of us as kids, two 8 or 9-year-old tots who were absolutely normal, and I’m saddened to realize we were feeling pressured, even back then, without even realizing it, by inflexible beauty standards. To this day, we both feel we’re not enough and would have loved someone to tell us, while we were still children, that we’re worthy of appreciation and affection, regardless of what we look like. This message is still almost completely absent from the educational system and the media we consume, starting from a very young age.

Illustration by Simina Popescu.

I’m 19 years old, I’ve just started university and it’s been a year since I was diagnosed with an eating disorder. This span of time blurs into a deep sadness, which engulfs me, and which my weekly therapy session soothes, but doesn’t solve. Quite the contrary. I plunge into a liquid diet because I’ve come to associate the sensation of a full stomach with deep repulsion. I can drink a bottle of wine on my own and still stand, although I fit into child-sized jeans. I wake up hungover and drink soy lattes, which are seriously very nourishing. I cry a lot when I Skype with my parents, because I feel miserable and, to a certain extent, for a while now, I’ve realized that I’m the one who’s making me feel miserable. I’m not content with the choices I’ve made, but no one’s ever told me that choices can change, that you can have a change of heart. So I take this out on my body.

At the same time, I model here and there for my photographer friends, older students, or yoga studios. Putting on dresses or sleeveless clothes scares me, because I don’t think I look good enough for them, but I adore the attention and astonishment of the photo session crew. Word about me gets around college, where lots of fashion design students are looking for models, because I’m tiny and have huge blue eyes and we live in a society where women are deeply infantilized. And when you’re anorexic, a part of you actually loves this infantilization.

In my mirror at home, I see myself as grotesquely deformed and now I know this is called body dysmorphic disorder. But it doesn’t change the fact that I can’t tell what I really look like. I long for the modelling sessions, because at least then I feel very beautiful. As if this whole destructive behaviour that I become aware of, but which I can’t stop, is worth it; finally, people think I’m beautiful. And beautiful means thin. Thin as can be.

It may sometimes seem that the strategies against recovering from an eating disorder are easier to come by than those for it. Dieting trends or self-monitoring apps, where you list what you eat, how much you work out, and how many hours of sleep you get every night are presented as solutions for increased productivity, but, to vulnerable individuals, they risk causing more harm than good and lead to unhealthy habits or obsessions with one’s physical aspect.

As with any disorder affecting both body and mind, recovery can be difficult, with ups and downs. There are various treatment strategies – usually a combination of psychotherapy and counselling from a nutritionist and, in severe cases, hospitalization is possible, to treat nutrient deficits. Generally speaking, you work with a therapist or psychiatrist who teaches you about the physical consequences of the disorder, helps you identify the factors that have caused and are maintaining the problem, and together you find strategies to preempt a relapse. A nutritionist or dietician can help you find a balance in the way you eat and help you make choices that are less influenced by emotions. In my case, I started with cognitive-behavioural therapy and began working with a nutritionist only two-three years later, when I realized I still didn’t know what balanced eating meant.

Illustration by Simina Popescu.

I’m 20 years old, still living in London with a girl from Hong Kong and we throw brilliant parties and spectacular dinners with 15 people crammed together in our living room, among huge pots of food. I let Virginia brown the onions and walk out of the kitchen, because I can’t stand to see how much oil she uses. Whenever we place the rice on the table and everybody helps themselves, I sprinkle a little bit onto my plate, like bird food.

I can’t remember how long it’s been since I’ve had rice. Still, it’s the first time in a few years that I’m getting my period, after months of conscientious treatment to rebalance my hormones, which are out of whack because of the anorexia. I’ve put on weight and feel less and less like myself, and this is driving me crazy. When I introduce myself to someone new, I feel like I have to start with an apology: ‘You know… this is a mistake, it’s temporary. This isn’t me. I’ll take care of it as soon as possible and you’ll be able to get to know the real me.’

I’m hoping to get over this stupid recovery thing as soon as possible, in order to lose weight again. I should’ve understood, at the time, that I was resisting recovery. After tearing a tendon by running too much, I have to severely cut down on workouts. I start boxing, because it uses my legs a little less than other sports, but my boxing partner likes to have something nice to eat after our class and I’m still feeling guilty. I don’t feel that I deserve a meal. I’ve worked up a gastric ulcer and have severe migraines when my blood sugar level drops too low, so it’s becoming increasingly difficult for me to restrict my eating. From throwing up too much, I’ve lost my gag reflex.

I’ve given up on some of my toxic habits, mostly because I’ve found a group of people who love to eat and do this guilt-free and non-obsessively, but also because my body was no longer able to handle it. A year ago, I would’ve gladly chosen getting run over by a car as opposed to putting on weight. Now, I sometimes manage to get a glimpse at a sort of parallel, intangible world, in which people’s lives don’t revolve around the obsession with their bodies. In my moments of clarity, I realize there are people who don’t see me as a number on a scale, but my self-perception is still much too blurry to be able to accept this.

After a few years in therapy, I’m slowly starting to let go of my relentless perfectionism and some of my self-punishing behaviours. They do, however, return at times of intense stress: a break-up, a failure, or a disappointment make me feel small, pathetic, and disgusted by my body. I distract myself with more sport and less food, toxic coping mechanisms, but which make me feel like I’m in control. I need this because, no matter how much I weigh, post-break up, I always think my partners were done with me because I wasn’t beautiful enough. Meaning: thin enough. And the feeling of power and control that arises each time the number on the scale decreases is my drug – one that’s hard for me to quit.

At 22 years old, I discover some things about my sexuality and start entering relationships with women. Only, they don’t make me feel any less dissatisfied about the way I look, compared to when I was dating men. On the contrary, I feel some anxieties arising, which I try to avoid – like when you step back a little to keep yourself away from the edge of the abyss.

My attraction toward women and the fact that throughout my life I’ve been comparing my body to the bodies of other girls, in locker rooms, gyms, at modelling sessions, down the street, or in bed, are closely and overwhelmingly related. I’m not ready to examine this node any closer, I’m just content with collecting dates and hanging onto each ‘you’re beautiful’ that comes from a woman whom I think is in a league way above my own.

I don’t like it when I find myself comparing myself to other girls, but anorexia and the marks it leaves behind tend to manifest themselves in rather anti-feminist ways.

At the moment, as I’m writing this article, I’m close to turning 24 and I know that I can look at any photo of myself taken over the past eight years and specify how much I weighed at the time, within a margin of error of 200g.

For the past two years, roughly, I haven’t thought at length about the way my body looks. I no longer have the energy to count my daily calories, starve myself, run till my nose bleeds. Over the past years, I’ve lived with my eyes averted, each time I felt the typical thoughts popping up in my head. Exhausted by my fast-paced lifestyle, I slid into near-complete negligence of what and how I ate and how much I exercised – and I thought this meant I was cured. This is what a non-obsessive relationship with food looked like in others, but I think I’ve yet to understand what this would look like for me.

During the pandemic, the public conversation on eating disorders intensified, which returned my attention to my old problem. I found out that eating disorder sufferers often cross several areas of this spectrum. It’s often encountered and it unfortunately makes sense that anorexia would drive one to the other extreme, closer to bulimia – from strictly maintained control to an utter lack of control.

Nearly a year after the coronavirus started ravaging the world, I started taking Cipralex for the depression and emotional exhaustion I was suffering from, after I had lost a few important people in my life and after innumerable waves of daily panic, induced by the dark news and numbers. My reaction at the beginning of treatment showed me my disorder was still with me.

I wish I had a positive conclusion, I wish I could say, ‘there, this is the story of how I was cured of anorexia, eight years later.’ US therapist Carolyn Costin, who specializes in eating disorders, believes that complete healing is possible, even in serious or chronic cases, and is based on a relationship of trust between patient and therapist, a system of emotional support and the patient’s need to start the recovery process, accepting that it will most likely be difficult and nonlinear. I also feel that complete recovery is difficult and sometimes so far removed that it may seem like a myth. But my story is not about a solved problem.

In Romania – and not only – eating disorders are rarely ever talked about; so rarely that it’s oftentimes difficult to realize you (still) have a problem. I’m glad more attention is being paid to mental illness and I hope that, as the public conversation gains traction, it is also released from the prejudice and stigma surrounding it.

For ten years, I’ve struggled to be thin enough, but the truth is that, because of the distorted way in which I saw myself, even when my real weight was concerningly low, I was never enough in my own mind. It was only during the pandemic that I realized that I was probably only halfway through the road to recovery and that I had plenty more work to do before I could have a balanced (enough) relationship with my own body.

This article originally appeared in Scena9 both in Romanian and English, in March and June 2021, respectively. Scena9 has an English section titled ‘English, please’.