Ben Little: People have used the term ‘culture wars’ for a long time, especially since the 1990s, and it’s often met with some scepticism. Today, as digital means of communication and expression have become dominant, what use is the concept of ‘culture wars’, and if it is useful how have these wars changed?

Alan Finlayson: We should start by making a distinction between two kinds of culture war, and then think about how they relate to each other. On the one hand there is the idea that there is some kind of significant political contestation taking place in or through the world of culture – that media and cultural practices such as subcultures (which may or may not be seen as political) are a battleground for larger ideological and political questions. Cultural Studies, and the work of people inspired by Stuart Hall, has made us familiar with this, with the fact that culture is an arena of hegemonic struggle.

But culture war can also mean something like a deep-level clash or contradiction between social groups on the basis of culture in a more anthropological sense – values beliefs, outlooks, ways of looking at and being in the world. That might include religious beliefs, or attitudes towards the kinds of things that religious beliefs often shape – such as gender, behaviour, or fundamental kinds of understanding of what the world or the universe is like. And that touches on dimensions not always fully captured by a term like ideology. Weber, for example, writes of ‘world images’, and of how these shape our fundamental ‘stand’ or ‘orientation’ towards the cosmos.

Left politics has sometimes displaced both these understandings of culture, failing to see the politically complex things going on in and through formally non-political culture, or ignoring the ways in which deep cultural orientations are a source of conflict on the grounds that they are ‘mere’ ideology.

But here’s the point of all this: the digital means of communication or digital platforms have enabled the intensification of both of these kinds of conflict over and through culture, generating a kind of resonance which further intensifies each of them in very significant ways. Culture – the means of communication, everyday activities, creative expressions online – becomes a primary domain for the playing out and intensification of that conflict over basic outlooks, and for the recruitment of people to the battle between them. These are conflicts that are shaped by the very deep orientations people imagine themselves to have, or perhaps really do have – orientations to the world, to politics, to the economy and to society. Simple-seeming cultural forms such as memes, or what look like minor online skirmishes over videogames, can invoke, and lead people to, substantive world-views and deep existential orientations to politics (and in ways missed by those casually observing from afar).

So, digital culture war consists of some things we know well (culture as a part of ongoing hegemonic contestation), some things we know less well (conflict over culture in an ‘anthropological’ sense), and a new way in which these interact due to online communications, which is not well understood and which is often completely misunderstood.

Annie Kelly: I often have a bit of a problem with the way that the term ‘culture war’ is used in popular media. When I was researching digital antifeminist subcultures and networks online, the topic would often be dismissed as if ‘culture war’ issues were a kind of distraction from so-called ‘real politics’.

‘Culture wars’ can imply something going both ways, and that often isn’t the case. For example, the way that antifeminist groups organise themselves online is a response to a perceived provocation, a feeling that masculinity in general is being demeaned. They have set up loose networks – blogs, forums, subreddits, and things like that – to carry out a sustained assault on any public feminist (and some not particularly public, such as teenagers with just a couple of thousand subscribers on YouTube or similar). These feminists have been stalked, and a sense of community is created among antifeminist groups out of collectively watching, targeting and harassing them. There’s no equivalent action on the other side.

A lot of feminist scholars have taken an issue with the use of ‘culture war’ to denote the backlash against women’s rights. Susan Faludi argued, in Backlash, that we should stop calling it a culture war: it’s feminist progress and then a sustained assault as a response. But I have no problem with Alan’s definition, which I think avoids those issues.

Rob Topinka: These groups that we’re talking about are on the far right or the reactionary right. And they are absolutely engaged in combat of some kind. They identify targets and they attack them and they have a strategy to do so. They see enemies everywhere. But the other side maybe doesn’t realise that they’re involved in this combat. A lot of the time, they’re unaware of it, which is a problem for the left or even mainstream liberal politics. They don’t realise that they’re the enemy of these groups. So they are unprepared for these attacks when they come. And then they also don’t realise the kind of recruiting that this confrontation achieves, and the way it engages people.

For participants it’s about community and self-discovery, a heroic quest to conquer one’s enemies. That links a lot to the conspiratorial elements of the culture wars. Sometimes we get distracted by the bizarre things QAnon followers believe or don’t believe, but we miss that they’re engaged in a quest and they’re striving for victory and that’s how they see themselves orientating to politics. That’s the way digital media recruits us to engage, and that’s why it lends itself so well to the culture war, because social media encourage that position-taking and then take people into ‘questing’.

Alan Finlayson: I think that you are both right about this. We’re not just saying it’s a culture war. It’s also a culture war and that’s really important. What I was trying to get at in my initial framing was that what’s at stake is recruitment to a whole worldview. Specific culture-war struggles, whether about trans rights or feminism or Black Lives Matter, are battles in a larger war, recruiting subjects not simply to disputes around particular political issues – things that you might vote on or get Congress or Parliament to deal with – but to a much larger world view that is fundamentally hostile to everything to do with liberalism and democratic welfare states.

And it then invites you to participate, to take on certain kinds of roles or identities. In that respect it’s really significantly changing not just what a political subject is, but how subjects conceive of and interact with a thing called politics, and therefore what politics is, for those people. That’s a really deep shift. Part of what is going on – and it isn’t just caused by digital media – is this much more profound change in the ways in which people relate to politics and acquire a political identity independent from the institutions that we’re used to: workplaces, trade unions, the press, political parties. Those things are still important. But something else is happening when this sphere called ‘the digital’ is so hugely prominent and dominant in people’s lives.

Annie Kelly: I find that people on the left will quite frequently say, ‘you know, well, that doesn’t really matter to me, I’m here for material politics, not this kind of ephemeral stuff to do with identity and identity politics’. But, like it or not, these tactics will be used on you, and will be effective, if you have any kind of interest in building a more equitable, fairer world. These tactics are not confined to targeting feminists, Black Lives Matter or trans activists. It’s a strategy that works particularly well against pretty much anyone on the left, whether they sign up to a war or not.

Ben Little: What is the genealogy of the culture war online? There are probably different timelines, but for me something qualitative changes with so-called Gamergate in 2014 and a new set of tactics emerge, which have been hugely successful. Is that where this comes from, where it starts? Is there a different history to digital media and politics which people don’t know?

Annie Kelly: Gamergate was a targeted harassment campaign against various feminist video game journalists and game developers, starting around 2014. It was probably brewing for a long time, as it was partly a response to the slow democratisation of the internet. Some people who viewed themselves as early adopters – although often they weren’t – had the attitude that the internet was supposed to be a libertarian space, free from any kind of social censure, government and laws, and that, as it became less of a space built for technology-oriented middle-class men with a university degree, this earlier ‘free’ internet was being lost or eroded.

There’s a long history of these sorts of anti-feminist spaces online, although, looking back at them, they are very tame compared to what we see now. If you’d never seen any kind of antifeminist rhetoric ever before you’d be appalled, but compared to post-2014 the language it seems very mild. What made that rhetoric heat up and get so vicious and angry was the sense that women – and not just women, but also people of colour and LGBTQ people and everyone else – were encroaching on the space of the internet and making it a less fun landscape to be in.

Lots of these spaces weren’t very networked. They were forums, blogs, etc, and didn’t really have any kind of cohesion, so there wasn’t much they could do other than grumble amongst themselves that they were the last bastion of how the old internet used to be. But then there was this general desire to connect things through social media, which had worked so well for lots of other kind of political movements in terms of galvanising support – for instance, the civil rights protests after Ferguson and Black Lives Matter. And there were a few attempts to get antifeminist social media campaigns going on Twitter and YouTube, which all failed for various reasons. Gamergate was the one that stuck. And then all these antifeminist reactionary groups and blogs and subforums connected and networked, which was very important for the emergence of the alt right.

Alan Finlayson: Another part of this is that lots of far-right groups were organising through computer communication in the 1980s, and were therefore used to it, and lots of people who were trying to work out how to use the internet in the early days were coming from those kinds of fringe spaces, either as ‘Californian ideology’ libertarians, or as far right.

Online there are a lot of forces aligned in pushing forward what you might call an anti-equality politics. There’s something about these digital spaces that intensifies and facilitates that kind of politics, because those who might advocate equality are not really using them. A parallel response would have been if all the liberals, social democrats and socialists had said in the 1950s, ‘no, we won’t go on television, we’ll leave television to the conservatives and right-wingers’. Some did think like that, but we can see now that ignoring television would have been politically crazy. But something like that is happening now. I’ve been in meetings and talks where digital communication is ignored, or seen as secondary to newspapers, or as a novel thing that might or might not turn out to be significant. The 2022 Ofcom report found that 94 per cent of households are online, and British people spend a daily average of 3 hours and 59 minutes online. It’s just where people are.

Ben Little: What is the actual politics? We’ve said it’s anti-equality, but what’s the spectrum of the politics that we’re talking about in terms of the right here. What is it that they believe in? What is being propagated? How are the arguments being presented? How can we characterise them?

Alan Finlayson: Digital forms of communication have profoundly changed the ways in which political ideas are formed, disseminated and spread. And one effect of that is a breakdown of the kinds of barriers and boundaries that you might expect to see between kinds of rightwing politics. In the past, if you were interested in conservatism, you went to a Conservative Party meeting and you read conservative newspapers, journals or magazines, which you had to find and pay for. Within that larger ideological family there might have been some fringe groups that produced their own publications like, say, The Monday Club, but otherwise political ideas further to the right were being shaped and propagated somewhere else entirely – at the National Front Meeting or the BNP meeting, or where specific bands of organised racists were meeting. The average conservative activist, let alone voter, probably wouldn’t go there because it would be difficult to find it and perhaps uncomfortable and strange. It would look and feel different, and you wouldn’t know the ideological codes and terms.

On digital media it’s completely different. Ideas, terms, phrases, arguments can just flow, immediately and very easily, between all sorts of different kinds of spaces. And you can find any as easily as finding any other. The size or status of a party doesn’t necessarily make them more prominent on the flattening planes of the internet; the most fringe view can find a platform that is essentially the same platform as the most mainstream view. So, one of the things that’s happening is that the distinctions and differences between ideological positions break down, and ideas move and flow.

I would propose that the way we understand right-wing politics in digital culture is as a broad range of anti-equality politics united in commitment to the belief that some people are naturally better than others – smarter, more powerful, more rational, more hard-working, more economically inventive and so on – and that those people naturally need to be running things. Liberalism is supposedly a false god because it doesn’t see that natural hierarchy, that natural order, and thinks that we can remake it and make people equal, and so is driven to overreach and impose authoritarian rules.

Now, that sort of proposition is not new. That’s standard radical conservatism and very common. It’s part of what animated, say, Goldwater Republicans and Powellite Conservatives. But the internet enables people to unite behind opposition to equality, and their arguments begin to cohere and be intensified by the fact they spread and flow, as fragments of arguments, as memes, as names and labels around which people organise.

Take a term like ‘cultural Marxist’, which begins as an antisemitic conspiracy theory about how people are plotting to undermine western civilisation by spreading sexual licence and encouraging immigration. It’s a conspiracy theory which predates the internet but which became popular on obscure and, for most of us, hard-to-read online forums – some already attached to far-right politics, some fairly free-form and unmoderated. From there it spread and developed and began to appear on YouTube, where it was a way of explaining to people how the world works: that there are these people who are trying to undermine western civilisation with their irrational totalitarian Marxist equality agenda, and that’s why ‘suddenly’ there is feminism in the workplace, and anti-racist rules enforced by the HR Department, or why comedy on the television isn’t full of sex and race stereotypes.

In time that starts to appear in below-the-line comments in online newspapers and magazines – the Daily Mail, the Spectator – and from there it starts to appear in the above-the-line op-eds, until eventually it’s in speeches delivered by conservative politicians such as Liz Truss or the current home secretary Suella Braverman. They blame Foucauldians or Critical Race Theory for stirring up discontent and for introducing opposition to the status quo and the free market. That’s a rapid spread of ideas, happening in a very short space of time, in a way that is new. There’s always been some spread and flow of ideas, but there’s also been some barriers and policing. But I don’t think you can really talk in the same way as we once did about the gradations between different strands of right-wing thinking, because ideas – world-images – are being carried (memed) by words and images across and between them at a rapid pace.

Rob Topinka: I think it’s maybe even worse than that because, in digital media, you either see it or you don’t. You’re in the network or you’re not. There’s a cluster of nodes around you and things from far across the network might never make it to you. They might be incredibly important on this other side of the network, but where you are, you just don’t see them. You’re not connected to them, and unless you make that connection, you’re not aware that they exist.

For example, there’s no Twitter: there’s your Twitter feed. There’s no space we can all go to called Twitter. You can’t overhear someone’s Facebook feed – there’s no shared ambience, no atmosphere. That makes it difficult, because then we get caught up in questions about who is active online and what are their ideologies. That’s incredibly important, but what also matters is which ideologies end up connecting and resonating, and that’s going to keep shifting all the time. It doesn’t necessarily matter what people believe or don’t believe, what matters is if that belief connects with something else.

Alan gave the example of the rise of previously obscure ideas like ‘Cultural Marxism’. Things like that are happening all the time. In the US, ‘Great Replacement Theory’ – the claim that immigrants are being let into the country as part of a plot to replace White people and bring down the country – has now left the far-right digital subculture and made it onto Fox News.

Another example: the former CEO of overstock.com invited a retired US Army Colonel onto his podcast after noticing he had been sharing a bizarre PowerPoint about how Trump could overturn the election. People in right-wing circles heard it and from there it made its way to Mark Meadows, Trump’s chief of staff. It’s very difficult to build a political analysis around this, because it’s just some guy who created a PowerPoint and shared it online.

You can drive yourself crazy trying to keep track of all the different pieces of content that are floating around. Until something makes the leap – to become something that matters – it could be completely irrelevant. So, we need to worry less about the specific content, and more about how it shapes people, how it orients people to the world, how it connects to their energy and emotion. So much of it is bizarre you end up wanting to explain it, and then people end up dismissing it and saying, ‘OK, well, there’s always been wacky people’, and then end it there – but that’s to miss how digital media work.

Alan Finlayson: Part of what I take Rob to be saying is that things which may seem ridiculous, and that may be believed only by a very small amount of people, can end up having tremendous leverage and spreading very rapidly. Most people don’t believe in QAnon. Nevertheless, some elements of it – that there’s a ‘deep state’ that wants to keep a hold of power, that they’re harming people, harming our kids – can resonate and begin to affect people in unexpected ways. That all connects with deep anxieties about modernity, industrial society, the body, and suddenly these things are spreading in ways that you can’t really understand as examples of a standard kind of ideological transmission. They are resonating at deep levels and shaping or shaking people’s worldviews.

Annie Kelly: I think that’s true, particularly for how QAnon travelled internationally. As someone who was keeping a pretty close eye on QAnon, I was still really surprised at what happened in London in 2020 when I attended a ‘Save the Children’ rally – a hashtag which had begun as a social media campaign by QAnon users as a sort of code when certain platforms began cracking down on more obvious QAnon rhetoric. Having watched that hashtag emerge online, I was expecting to find people there espousing what the journalist Siddharth Venkataramakrishnan has called ‘QAnon proper’ – the conspiracy theory that Donald Trump was fighting a secret battle with the deep state, and that mass arrests and executions of the US liberal elite were just around the corner. I was expecting to see the usual kind of faces that I’d see at a Tommy Robinson rally, for example. But it was mostly young mothers, many of whom had brought their children with them. And most didn’t know that they were talking about the QAnon conspiracy theory in its formal sense – they viewed themselves more as engaged in a kind of spiritual battle with elite paedophiles, and the people and institutions they referenced were nearly all British.

I spoke to some of them and began to understand that the conspiracy theory had moved through parenting groups on Facebook and yoga groups on Instagram. It had lost almost all of its US character, its association with MAGA and with Donald Trump and anything to do with Q being a top security official. It had taken on a very new age, spiritual quality, which was very different from what my American co-hosts on QAnon Anonymous were encountering at Trump rallies in the United States. It was an idea that had reproduced itself through Facebook groups and Instagram hashtags.

Alan Finlayson: Another important thing is the way in which a lot of this reactionary digital cultural politics proclaims itself very deliberately as the counterculture. Paul Joseph Watson, a prominent British based and very successful, very right-wing YouTuber with around 2 million subscribers, has sold T-shirts with the slogan ‘Conservatism is the new counterculture’.

This year saw the fiftieth Glastonbury Festival, something which was once outside of the mainstream, an amateur DIY festival later associated with causes that were also outside of the mainstream, such as CND and Greenpeace. Now there is no pretence that it’s anything other than what it is – a major commercial event, on the social calendar for people with leisure time and money, of all ages, and fully covered by the state broadcaster. There is little to nothing ‘countercultural’ about it. Reactionary online cultures have taken up that mantle, claiming opposition to ‘the man’, which means opposition to the culture of Glastonbury Festival, and this can also encompass (as Glastonbury once did) opposition to science or to scientific authority, to the state, to politics, to anything that can be construed as telling you what to do and infringing on your freedom (wear a mask, don’t use certain words, etc).

This politics is claiming for itself the position of being the part of the culture that makes fun of those authorities, that will tell the jokes that ‘you can’t make any more’ and risk being ‘cancelled’ for taking apart ‘orthodoxies’ – state-backed policies of gender equality for example. It’s making itself seem very exciting, a space of something that really is ‘alternative’, and, crucially, something that you can join in with. You enter its spaces and become a creator making your own videos, gifs, images. You can be a participant by commenting, by reposting or, as Rob was saying, by ‘questing’ – taking up a full role and becoming a hero in the struggle against ‘liberals’, ‘the left’, who are trying to dominate us and tell us how to live our lives. I think all of that’s hugely underappreciated by people on the political centre or left.

Annie Kelly: Yeah, that’s interesting, this affect – of ‘rebelling’ against the ‘woke’ system, the moralising scolds who say you can’t make that joke and you can’t do this – that idea looks to me to be somewhat on the wane in this digital landscape. Increasingly, the star that’s rising is this reactionary, ‘think of the children’ political culture, but with a ‘fun’ new digital sheen. Libs of TikTok, for instance, is a Twitter account which essentially curates a feed of LGBT teachers in the American public school system who have made TikToks. It makes them targets by calling them groomers and paedophiles, publishing their address and place of employment and so on. There’s a continued panic about drag queens or fetish gear at pride marches, where children may see them. To me it feels like the continued influence of QAnon, even among people who wouldn’t say that they believe in QAnon at all, and find it a little bit embarrassing.

Rob Topinka: The other thing to add to this, even though the force of it has fizzled a little bit, is Covid scepticism, the rejection of the various lockdown rules and masking, and opposition to a perceived alliance of the state and Big Pharma. I think those things are very different, but they’re linked in the sense that there’s a lot of concern about the body and bodily autonomy, and wanting to free the body from people who want to control you or corrupt your children.

Another good example is cancel culture, which has waned online but is now on the rise on opinion pages. It’s the debate legacy media is having – a debate that was had online five years ago has now filtered into the mainstream. The New York Times just published a controversial op-ed about trans naming practices which would have been at home five years ago on some of these far-right spaces.

Ben Little: There’s classic ‘dog-whistle’ language that politicians or people online or on TV might use – like Cultural Marxism – which I think we might recognise. But they might also be using other terms or phrases, other frames of reference, which, unless you’re in those circles, you don’t understand. That strikes me as really important. How can we understand the relative influences of these two things at the current moment? How can we disentangle it? Or do we have to understand them together?

Alan Finlayson: In some respects talking about ‘digital media’ as something very distinct is to have gone wrong already. A lot of people in the field talk about ‘post digital’ now, meaning that there just is no meaningful distinction between online and offline. For example, I don’t subscribe to a print newspaper and I don’t have access to broadcast-to-air TV. But I read lots of newspaper articles and see a lot of television. I’m accessing it all through digital portals, and that’s important – it makes a difference. It means I can move seamlessly from Twitter to a Guardian article, which links me to footage on YouTube of someone talking in parliament, and then I click on the video that comes next and I’m watching some commentator talking about whatever is going on.

Trying to understand that in terms of the separation between old and new media is immediately confusing. You have to think about how things move between them – and how, say, a lot of so-called ‘print’ media tells you about things that are happening online, reporting on what people tweeted about some event – but also how a lot of digital commentators on YouTube will make videos in which they talk about things that were in the newspaper, and even put quotes from the article on screen and read them aloud while editorialising (although the newspaper here was of course accessed online). So there really isn’t a distinction when it comes to the ways stuff circulates and is consumed.

And, to reiterate, the reason it is different is the way it is being accessed through this single portal. We read newspapers, watch television documentaries and share thoughts on them through the same interface (a computer or a phone), and that dissolves distinctions between kinds of outlet, between who has and does not have sanctioned authority. Because you don’t need to be a by-lined columnist or a celebrity to be significant, although that can help. Anybody who can fit themselves into the network and find something that resonates in the right way can become a key node in these larger networks.

Annie Kelly: Something I’ve noticed with Tucker Carlson, who pioneered this approach, but now I’m noticing other Fox News hosts also do it, is that they will create a news story out of what are essentially popular memes going around conspiracy Telegram channels and spaces like that. With Tucker Carlson, the alleged biolabs in Ukraine were first mentioned on an anti-vaccine Telegram channel, which was in turn pulling it from Russian State media from the war in Ukraine when it first began in 2014; this then became the claim that Covid had in fact been cooked up in a lab in Ukraine as opposed to China, as they’d all thought before. Then this filters through to Tucker Carlson, who gives it a news veneer, and it gets shared back on the Telegram channel as proof that they were right all along. I’ve seen Laura Ingraham doing this with upcoming climate lockdowns as well.

This is why it’s obvious to anyone studying far-right digital spaces that, once you’ve seen some kind of language get used somewhere like 4 Chan, it’s only a matter of time until it eventually percolates. It’s usually not that long after I’ve noticed a new turn of phrase on one of these channels or groups that it will be on Fox News – perhaps the following week, or it might be a matter of days. And largely they’re taking a term which is punchy – ‘biolabs in Ukraine’, ‘climate lockdowns’ – and then, through lots of speculation and theorising, they launder it into a plausible-sounding news story. It’s very rapid now. I think the first time I noticed when a politician used ‘Triggered’ it was four years after I’d first seen that word used on 4 Chan. Now I don’t think it would take that amount of time at all.

Ben Little: I have also been thinking about the scale of some of these channels, and the gravitational force that they have even when there’s not a direct relationship with traditional media. Take the Joe Rogan phenomenon: 20 million people watching six-hour long videos of a stoned wrestler having conversations with internet celebrities and sometimes politicians like Bernie Sanders, and also with conspiracy theorists – and presenting them all as being of equal merit. People who consume that can’t have a lot of time to consume much other media. That’s a different way in which ideas are being formed and shaped, and a different media culture altogether. How significant are these channels?

Rob Topinka: Speaking from a media studies perspective, I don’t think we’ve quite figured out how to talk about it yet. So much of our media criticism comes from a mass culture era, and the internet is not mass culture. There are lots of very big audiences, but there’s no mass audience.

We don’t have a good way of talking about this, and I think that’s why people sometimes resort to invoking ‘the algorithm’, even though most people know there’s no algorithm: there are many algorithms interacting with each other and with what we do online. Proceeding as if there is one algorithm shaping what we see is attractive, because it gives us a way to replace the idea of the ‘broadcast’. There are all these islands of large, very large, audiences that are connected in their own little communities but not connected outside of them.

Alan Finlayson: It’s important to emphasise the scale of, say, Rogan, with 20 million people, which dwarfs anything achieved by Newsnight or the Guardian or the BBC. But part of what is peculiar is that in the UK we are talking about this American podcast series. That’s because one of the things the technology does is break down the traditional geographical borders of media consumption, so that people are reading and consuming content emerging from an American political context, bringing it into the UK and adapting it. That means you’re getting different kinds of arguments and ways of thinking and keywords coming in from different countries. And it isn’t just Britain and America, it’s much more complex and global than that. People such as Rogan are important nodes in a network – he’s clearly hugely important for amplifying particular people.

Ben, you asked about the time it takes to watch it all. But with something such as Rogan you don’t have to watch it, you can listen to it on the bus, or while walking around or while cooking, or you watch clips of it while also watching a movie. It’s a very different mode of consumption, one which flattens out these different kinds of things. Part of the power of Rogan comes from the fact that people don’t necessarily think of themselves as watching or listening to a political show. It’s just something that is interesting, funny, with new ideas you haven’t heard and so on. It’s engaging.

People often think it’s all two-minute videos or short flashing images. But TikTok aside, the content can be long discussions and reflections, some of them hours-long. They aren’t just asserting a position on the news of the day, but also presenting an explanation for the news of the day, of where things are coming from. And that’s something you don’t really get from a lot of legacy media.

Annie Kelly: You also get a parasocial relationship with Rogan, or with whichever YouTuber or influencer that you follow. They’re something more than a journalist to you. If you’re listening to six hours of somebody on the bus, on your way to work or while you’re washing up, that’s kind of more like a friend. There’s a particular closeness which this digital media model offers. You approach ideas differently when they’re transmitted to you by someone that you perceive as being above you – an establishment journalist, shall we say, or a taste-maker of some kind – as opposed to someone who is quite a large part of your life. And even though you logically know they are not your friend, you feel like they are, and approach their ideas in a different way.

Rob Topinka: When people try to combat misinformation and disinformation, it sometimes seems as if they think people have got a list of ideas and thought, as if content came in over my feed and I chose to believe it. But people have developed these parasocial relationships, deep emotional connections. If you were to quiz the average QAnon follower on the QAnon canon they probably wouldn’t know all of it. But they would know who they follow and who they’re connected to. To combat this sort of thing we may have to stop thinking about things like fact-checking and debunking.

Ben Little: We’ve been focused very much on the right, but what counterbalancing forces are there on the left? Is there anywhere near as much presence, power, influence as there is with these rightwing actors? And if not, why not?

Rob Topinka: The short answer is no, the online left does not have the same influence, although there are certainly left-leaning and even radical formations online, for example Black Twitter, Tumblr feminism and BreadTube. But the form and structure of online communication favours reactionary thinking. For reactionaries, everything in the present is a symptom of the loss of a mythologised past. There is not much friction between that worldview and a lot of online discourse, where readymade negative takes resonate.

Part of the problem is also a larger dynamic – that ‘mainstream’ conservatives are more willing to engage with the far right than ‘mainstream’ liberals are with the left. But I think that the basic ‘affordances’ of digital media favour the right in a way they don’t favour the left, because the right wants to restore a lost past, while the left needs to build something new. And that’s not as easy to do online.

Alan Finlayson: Outlets on the left often seem to act as if their position has ‘normal’ foundations, and the task is, as it were, to measure the distance of others from that norm. They all proceed on the basis that ‘we all know’ that racism is bad and that ‘the right side of history’ is progressive pluralism. It’s not the same on the right, even though sometimes the voices on the right are very establishment voices, and even though they are clearly drawing on a common-sense ideology and rigid claims about nature. Their position is that what they think is not the norm, that ‘most people’ don’t think like they do, and that they are last defenders of civilisation against liberal orthodoxy. That’s the war part of culture war again. And so they’re much more explicitly and consciously partisan, and they’re much more ready to lay out what they find wrong with the world view they’re critiquing and what their world view is.

Rob Topinka: Does this go back to where we started, where the right, the reactionary right, is fighting a culture war that others are not fighting?

Alan Finlayson: I think that, despite everything, most people broadly accept certain principles about equality and fairness being good things. My worry would be that when the left intervenes it does so on the assumption that everyone knows why those things are good and important – equality, fairness, democracy – and proceeds on the basis that once everyone sees these are under threat they will all be on board. But it doesn’t actually reinforce, explore or affirm these fundamental orientations to the world. Whereas what’s happening on the right is an active (perhaps counter-hegemonic) attempt to say we don’t believe in those things and you shouldn’t either; here are some arguments or some reasons, or some stories, or some images, or some lies, that show you it’s not true.

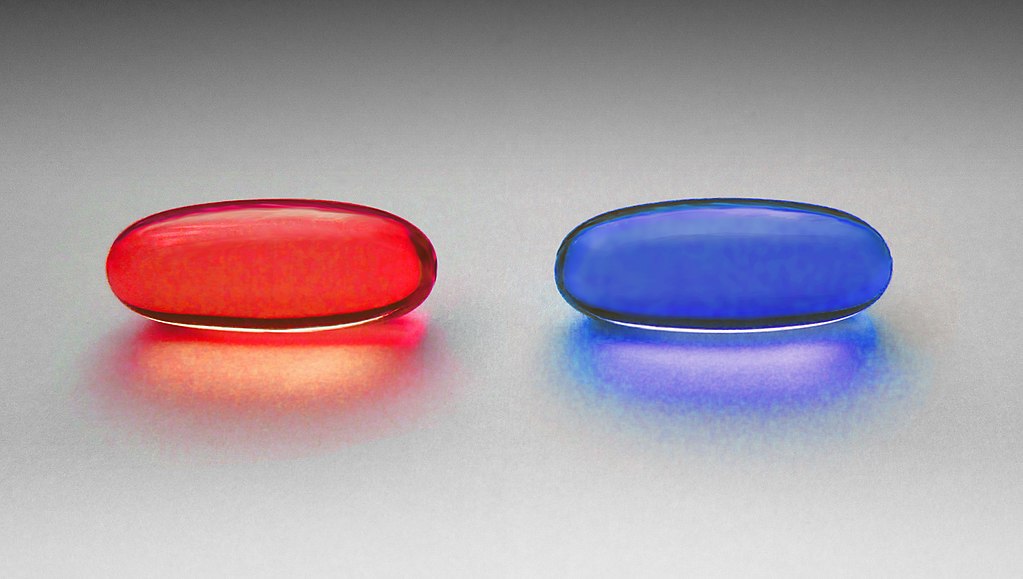

That’s what’s taking the red pill is. The ‘revelation’ is that everyone’s not really equal, and that one is being screwed over not by exploitative employers but by the people ‘imposing’ equality, who need to be resisted. The problem is that the left doesn’t often engage in politics any more at the level of fundamental ideological orientations. It’s good at accepting certain kinds of liberal ideas about pluralism, individual choice and freedom from harm, and it’s good at expanding the reach of those, but it’s less good at raising fundamental questions, because it thinks they have been settled.

It is also worth saying that when a new means of communication emerges it can take a while to work out the forms that political expression takes. It took the left a while to discover in the nineteenth century that certain kinds of pamphlet and certain kinds of song and certain kinds of public talk were the means to disseminate ways of thinking. The right has been quicker at working out how the digital medium can work for it – partly because, as we have said, it was there earlier, and partly because it is taking up the countercultural position.

And this is also a thoroughly commercial medium – it exists primarily to make money. So it suits people who are happy to think in those terms, and to do whatever is successful and makes money.

A fundamental aesthetic question faces the left: ‘what will be the form of online expression through which we can communicate our politics?’ I don’t think we’ve actually got an answer to that. It might look a little bit like bits of the investigative journalism podcast QAnon Anonymous or Novara Media, and perhaps a lot more like Contrapoints and other very creative Youtubers who are finding ways to write and perform quite long and elaborate essays that get millions of views. It might be that it recreates older forms – like pamphlets and public lectures – or that it looks like something else entirely.

Someone like Jordan Peterson has practised. He went on YouTube early and spent years honing a style that would work to communicate his politics and be extremely remunerative. Few on the left have really done that experimentation.

Annie Kelly: I can get very frustrated with people who share my political sympathies, but still lack recognition about how your digital environment shapes you and the way you approach different issues. I think there can be a quite stubborn belief that ‘my principles are my principles, and I simply look at the facts and see where they lead me’. But none of us are looking at all of the same facts any more. Even if we are reading the same article, we probably got it from a different source, probably with different commentary. I try to maintain an understanding that there are very, very few people who do not have a digital environment anymore, and that this fundamentally changes the way that they approach these ideas, including us.

Alan Finlayson: Clearly, a fundamental aspect of all political practices is communication, since it’s through communication that people share ideas and form common views, and can act collectively. In the present day there is no form of political communication that takes place that does not – in some way – go through digital platforms. Most, if not all, of the most significant things have occurred in British politics in the last five years have happened as they happened because of digital communication: Brexit, Covid scepticism, Johnson’s election, Corbynism.

Annie Kelly: Gender Recognition Act reform.

Alan Finlayson: Yes, all of these are part of long histories of campaigning, but you cannot understand any one of them if you do not understand the way in which they were formulated and communicated online. It would be like trying to talk about the Reformation without mentioning the Bible and printing.

This conversation was held and transcribed in early July 2022.