In the summer of 2017, I spent seven weeks as a residence artist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. The PIK, as it is commonly called, is located in the buildings of the old Astrophysical Observatory on the summit of the willow-grown Telegrafenberg hill. This is also the site of the famous Einstein Tower, a white structure with rounded walls, designed in an expressionist spirit and named after Albert Einstein, whose theories on relativity are tested there. I was provided a studio in the Kleiner Fotorefraktor, or little observatory, a smaller version of the main building, and allotted the task of determining possible talking points between literature and science in this era of climate change.

When it comes to the importance of the PIK scientists’ work for the rest of the world, there need not be any doubt. The men and women who work at the institute, mapping and studying the reactions of different natural phenomena to global warming, do so in the hope that their work in the field – at sea, on glaciers, sands, mountain peaks, and valley floors, at both poles – and in the digital physics models that they have developed in their supercomputers, will make invisible threats tangible and sound the alarm for those threatened: the public, national governments and big businesses. However, PIK’s natural scientists have begun to raise doubts about people’s defensive responses (and have even begun to question whether mankind possesses the intrinsic ability to respond to its imminent extinction). And so they have called for collaboration with poets and artists – that segment of society that has, through the centuries, also made it its task to bring the hidden into the light and make it visible to the human eye.

One of the first ideas that I had after accepting the invitation to Potsdam was to make the nineteenth-century poet and naturalist Jónas Hallgrímsson my traveling companion and advisor in spiritual as well as material concerns. Jónas is the national poet of Iceland and the person who, beyond all others, taught his countrymen to behold the beauty in the natural elements. In days of yore, these shaped the land that the Icelanders had settled, and today still challenge their existence with harsh weather and the violent agitation and outbursts of the earth. In his poems, scientific perspicacity regarding the nature of the physical world is combined with poetic humility towards its power. These works convey man’s smallness in the face of creation, which is ferocious and lofty at once, a veil over the face of the Creator and a mirror of the being that the Creator made in His own image:

Eternal snow shines in my eyes

out and south and west it lies,

in and east the same I see.

Individual! Robust be.

(‘Snowbound’, J. H.)

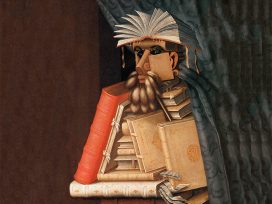

Icelandic poet, author and naturalist, Jónas Hallgrímsson. Photo from Wikipedia.

Next to the collected works of Jónas Hallgrímsson on my desk in the little observatory, I lined up other books that I thought might be of use: The Conspiracy Against the Human Race by Thomas Ligotti, In the Dust of this Planet: Horror of Philosophy (Vol. 1) by Eugene Thacker, and Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Experimental Futures) by Donna Haraway – all of which deal explicitly with mankind’s threats to itself and its possible disappearance from the face of the Earth. Mankind alone recognizes its worth as a species, and it is up to it to fight for its existence – against itself – with the same tools of the human intellect that now endanger it. I also had Le Rire de la Méduse by Hélène Cixous, which is a classic reminder of our ability to recreate our language and ways of thinking by finding new wellsprings inside ourselves, in places not found on the maps of those banes of our existence: patriarchy and capitalism.

I soon realized that my project involved two main tasks. On the one hand, I needed to face, boldly, the physical and natural-historical findings of the PIK scientists, together with their predictions of the consequences of climate change for life on Earth. On the other hand, I had to find a way to answer the PIK’s call to me, as a writer, to contribute to saving the world. Both required some effort. It would perhaps be easy to throw up one’s hands and surrender in the face of the fact that human behaviour over the past three hundred years has done so much damage to the environment that we are entering a new period of mass extinctions of animals and plants (behaviour that is rooted in western mechanism of exploitation, colonialism, and privilegism, simply put). Along with that inclination toward surrender comes a feeling of powerlessness, scepticism that one writer’s literary creation can bring about results – no matter how high an opinion one has of oneself and one’s works. What is more, I felt a twinge of the healthy stubbornness that crops up in most writers whenever an attempt is made to dictate to them, or to point out to them worthwhile and even urgent issues in the world today, however gently they are approached, or however glaring the need is.

Jökulsárlón, Iceland. Photo by Marco Verch from Flickr.

‘The latest news of the tipping points’ was the title of a talk that I attended, given by one of the professors at Telegrafenberg. In it, he reviewed the status of various natural phenomena that have already been significantly affected by global warming, including weather systems, icebergs, lakes and seas, with the term ‘tipping point’ referring to the moment when these changes in nature and the climate become irrevocable. When the Greenland ice sheet has melted below a certain elevation, it will no longer be able to sustain itself and will continue to melt to nothing; it is already in the process of vanishing, and this is happening faster than the most pessimistic forecasts predicted. It is such information that disheartens an Icelandic poet, that causes him to lose ‘robustness’, as Jónas Hallgrímsson might have put it. Yes, the big question is what it will take for mankind’s ‘tipping point’ to be reached. What will finally bring mankind to see clearly that global warming is nearing a point of no return, compelling it to raise its defences and do everything in its power to slow down the changes and respond compassionately to the plight of those already suffering the consequences of them? A large part of the problem is, of course, that the societies most responsible are still the ones least affected. People living in the peripheral areas of the earth, the so-called indigenous peoples, or in places where survival is dependent on the sea level, precipitation during the rainy season, or the life (and death) of essential entities such as coral reefs or forests, are already wrestling with the consequences as they are manifested in wars, hunger, and refugeeism.

At a meeting that I had with the director of the PIK, Hans Joachim (‘John’) Schellnhuber, shortly after my arrival in Potsdam, we discussed the challenge faced by every writer in taking on the changes facing the world and deal with them independently under the premises of literature. It is one thing to write articles and essays, or discuss issues at conferences and in the media, and another to create literature shaped by the subject matter in dialogue with the history of literary attempts to deal with such topics (the imminent destruction of the world or something similar, for example), in poems great and small, novels and plays, ever since the earliest days on Earth of that storytelling creature, Homo narrans. We agreed that the arts of language and the natural sciences were siblings, and that nature alone, humanity in nature, and the nature of humanity are today, as throughout history, the subject matter of both.

A recent discovery in the world of science was a moth that feeds on the tears of small birds. These moths flutter up to the sleeping birds, extremely quietly, land on the birds’ feathery heads, extremely lightly, unfurl their proboscises and slip the tip beneath the birds’ eyelids, and drink their fill without waking them. I told Schellnhuber that this discovery had no doubt already found its way into one or a number of the thousands of poems that had been written since. Perhaps one of those poems could bring about a revolution in thinking? He believed that it would take more than that.

Icelandic puffins are starving due to climate change. Their favorite food, sand eels, are in decline near their nesting grounds due to rising water temperatures. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

So it was that I spent the summer of 2017 in a little observatory in Potsdam, pondering the role that a writer could play in times of climate change and global warming, and the devastating consequences that these are having on humanity’s environment and survival.

Toward the end of my stay, I acquired a copy of the book Religion in Environmental and Climate Change: Suffering. Values. Lifestyle, edited by the Norwegian theologian Sigurd Bergmann and Dieter Gerten, a scientist at the PIK. As the title of the book implies, it deals with the attitudes of different religions toward this threat to the earth. Among the book’s subjects are Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’, in which the Pope exhorts Catholics to take responsibility for nature, which God entrusted to man’s stewardship, and to display compassion and brotherly love to those bearing the brunt of the disastrous consequences of climate change. At the presentation of the encyclical at the Vatican, Francis had at his right hand John Schellnhuber, making it clear to all that Mother Church was walking hand-in-hand with science on this path. The book discusses the denial by American eschatological Pentecostals (who are convinced that we live in ‘end times’ and await Jesus’ second coming) of the conclusions of the same sciences. It also describes how the mythological worldview of the Sakha people in north-eastern Siberia are changing as global warming negatively effects seasonal weather patterns and the subsistence modes that these people have developed over the centuries in order to survive at the boundaries of the inhabited world.

The correlation of the contents of this book with everything else that I had been reading, viewing, hearing, and considering helped me formulate the following conclusion.

Only by putting literature into an ecological template can we understand what role writers might have in saving the earth and humankind. In the ecological template, literature appears as an organic whole, stretching back to the dawn of humanity. Sometimes, literary works are spoken or sung, sometimes acted out or written, often in a language spoken by many, more often in the languages that belong to only a few. It is an entity that changes constantly according to content and circumstances, in both its clearest and most obscure manifestations, but that plays a key role at all times in the survival of the people that cultivate it.

The task of those of us who create literature in one way or another during the era of climate change is thus – to put it simply – to ensure that it has a secure place in human existence. Together, we are responsible for the ecosystem of literature as a whole, whether it is the freedom of speech of conservationists in Uruguay or poets in China; the access of Syrian writers fleeing war to literary communities in their new countries, or Dalit children in Jaipur to reading lessons; or the preservation of the Paiute language in Nevada and the library in Timbuktu. It is up to each of us to decide how much light, and what type of light, we wish to shed on the upheavals facing us.

No more than in the natural sciences, the ecological approach to literature permits different aspects of its ecosystem to be evaluated on the basis of hierarchy. The Sakha people’s dying story of the blue-spotted Bull of Winter with its huge frozen horns might reflect the mentality that we need in order to survive as a species. The death of the moth that drinks the tears of small birds can eventually lead to the loss of the forest.