“Indeed, part of the denial of death in this culture is vast expansion of the category of illness as such.”

Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor, 1978

I am aging, as we all are, though most of us don’t want to see it. Not being someone to shut her eyes before something so, to say the least, unsurprising I want to know more about what I can expect. Especially because, by all accounts and against all hopes, aging seems inevitable.

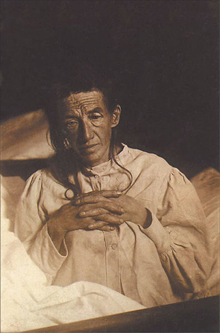

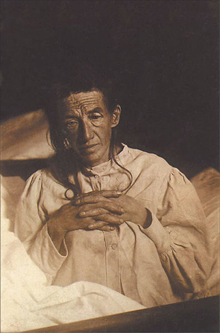

Auguste Deter. Alois Alzheimer’s patient in November 1901. First described patient with Alzheimer’s Disease. Source:Wikimedia

This is supposed to be easy, after all there are old people all around us, in the streets and supermarkets, on public transport, living next door. Yes, but they don’t live with us. In our urban western culture, old people no longer live with younger ones and they don’t die at home. They live alone or in homes for the elderly, out of sight. They die in hospitals, tucked safely away from the public and even the private eye. The older they get, the more invisible they become. And when they are visible, the elderly are perceived as a problem, a useless and expensive burden to individuals and society. In most cases they are ill and demanding. If we are emotionally related to them, we try to help them, or convince ourselves that we are doing “all we can”. However, this concern usually translates into money we pay to someone else to take care of aging parents. Caring doesn’t mean we are keen to understand their condition, until the moment when we realize it is becoming ours. But, by then, we too are isolated, alone with our needs and sorrows.

My beloved paternal grandma died in a nursing home and my maternal one, as well as the grandpa years before her, died in a hospital. None of their children, my parents, aunts and uncles, wanted them in their homes. I remember my mother crying after her mother’s calls. I also remember my father justifying his decision to put his mother in a nursing home by saying that our apartment was too small to have her with us. It was true, but when my brother and I were little, she lived with us in an even smaller apartment. I understood early that old people live alone and end alone. I was lucky because my mother was independent until she was almost eighty. She then moved to a nursing home on her own will, probably because she saw no alternative. But not even then did I get a better insight into what really happens to your aging body and mind, how your vitality seeps through your fingers and you end up being unable or unwilling to step out of your own home, instead sinking deeper and deeper in depression. How it feels to be invisible even to your children. Once there, she was better off surrounded by other people. But living in one room, with a single cupboard, one shelf and a few family photos, seeing both your possessions and your identity shrink to a minimum – what does it do to a person?

Only after my mother’s death at eighty-six, when I stopped being a child, did I start to think about my own aging. What could be more natural for a female writer than to reach out for books, for literature written by women about their experience? Aging might not be an easy or entertaining subject, but it is a common enough phenomena to expect there to be lots of books out there.

Yet it turns out that aging, in literature like in life, is a suppressed and hidden subject. That is, when it is not commercialized.

To be sure, there are plenty of books on the topic of aging – academic works on the one hand, a sea of self-help manuals on the other. Then there are writers approaching old age with humour, like Nora Ephron in I Hate My Neck and, especially in the USA, optimistic memoirs by women (published, I suspect, just because they are optimistic). Many of them express the view that old age is great because they are finally free to do what they want, now they are no longer under pressure from family or society. There one finds advice such as: “Take that trip you ‘always wanted to’. Learn to skydive. Flirt with a stranger. Close your eyes and point to a place on the map and then head out.” There’s nothing wrong either with humour or optimism; there must be people for whom sixty or seventy or even eighty looks just like that. But in all probability, they are a tiny minority. You can do all that if you have enough money, which most people don’t, and if you don’t have high blood pressure or some other ailment, which most people at that age certainly do. Nowadays people live longer than ever before, but are they really looking for a skydive or a flirt? And what happens afterwards, from eighty onwards? Generally speaking, the inevitable loss of mental and physical capacity is not something to look forward to, I would think. Or, as it happens, to write about.

Being over sixty myself, I am less interested in life-threatening activities, to which I count both flirting with strangers and skydiving. I admit that I prefer works of literature about the aging of the female body and the difference between internal and external perceptions of it. My search started, paradoxically enough, with male writers. A few years ago I noticed that important authors like Philip Roth (80) in Everyman and J.M. Coetzee (73) in Slow Man and Diary of a Bad Year had written novels about old age as experienced by men. And while most of it – loneliness, the feeling of exclusion, memory loss and the humiliation that goes with it – is a common experience to both men and women, there are also differences, for example on the physical side. Suffice to say that the weakening of libido is a great preoccupation of “everymen”, while – based on my mostly theoretical insight – women seem less preoccupied with its symptoms, if at all. In short, reading Roth and Coetzee, it’s hard for a woman to identify completely with their descriptions of aging.

Of course, I expected to find similar books from female writers, especially of my generation, since they had already articulated all aspects of female life and experience. Or almost all. Feminist authors, from Simone de Beauvoir in her classic The Coming of Age (which my daughter gave me for my forty-first birthday) to Betty Friedan, Nancy Friday, Shere Hite and later Naomi Wolf, write about the old age mostly from the historical, social and psychological perspectives of women living in a patriarchal society. An important work by Germaine Greer, The Change: Women, Aging and the Menopause (1992) ends precisely there. But what happens next? Do women die? Or become completely invisible? That’s how it appears if you’re looking for a tell-all book about aging. However, women continue to live even after the menopause and need identification figures to help them articulate that period of life.

Not that ordinary women are entirely without role models: when the American feminist icon Gloria Steinem celebrated her seventieth birthday, the American press published a photo of this extremely beautiful woman under the caption: “This is how seventy looks!” When a journalist asked her about her relationships with men, she said: “I am not interested in dating. I have a chosen family of friends. They include old lovers, who turn into friends. It’s so wonderful. All the brain cells that were dedicated to sex, they’re free for other things now.”

Well, it seems to me that not many brain cells were dedicated to sex in the first place, it is probably just the opposite. That apart, the fact that this seventy year old woman was even asked about men speaks for itself about society and the culture we live in. True, she looks fifty and is supposedly a role model for aging, which doesn’t exclude sex. Is the logic behind the suggestive question that, if she can do it, so can every woman? But Gloria Steinem is a rare beauty and how many women can claim that? Yet the idea, or rather propaganda (yes, propaganda, I am using this ugly word deliberately), is that even if you aren’t young, you should at least look it, because to look old is not acceptable in a society obsessed with appearances, youth, productivity, activity and sexuality.

If you aren’t beautiful like Gloria Steinem and don’t look beautiful in your seventies, try Amazon for help. Looking for books on aging, you will find more than you bargained for: a whole list of books about beauty and how to get it. From the use of hormones to the use of garlic. Under “Bestsellers in Aging” you will find The Anti-Aging Beauty Bible and Aging Without Growing Old. I was fascinated to see that the search engine will offer you exactly the opposite of what you are searching for. The idea that you don’t want to get old is already built into the search algorithm itself.

Perhaps it is only Americans who are blessed with an optimistic view of old age where it’s possible to flirt with a stranger at seventy or eighty or – who knows – at ninety. The problem is that they impose it on the rest of the world. There’s a whole beauty industry out there, helping women to achieve that goal. Emancipated or less emancipated, women are easily persuaded by the fashion, cosmetics, body-shaping and food industries, so that today it’s not necessary to look old; so many products are at their disposal, all you need to do is buy them. Indeed, it has never been easier to hide your age. Look at another role model, Jane Fonda: the right food, special gymnastics and cosmetics (not to mention a little bit of plastic surgery) and every seventy-six year old woman can look twenty years younger – that is, still able to show herself without feeling shame. Therefore there is no reason to look your age; on the contrary, it is indecent to “let yourself go”. Not only impolite, but indecent, just like spitting in public or even worse.

The dominant ideology of eternal youth (and health, which is just another word for eternity) suggests that with the help of science, it is possible not only to look good but to overcome any illness that befalls you and to live long too. The latest findings in biology, stem cell research and glycobiology have already been put to use in the battle against aging. One cosmetic product based on glycans is the suggestively named Forever Youth Liberator.

Could this social pressure on the elderly, and especially women, be the reason why women don’t write literature about their aging? The reason why, on this particular issue, they seem to be shy? Why aging belongs to the private and not the public domain? For the female peers of Roth and Coetzee, the experience of aging seems an uninteresting topic for literature. Yet this seems strange – if not outright weird. As if with aging, female life stops, or at least stops being worth describing.

But something else might be taking place: that women’s literary writing on this particular topic has been almost completely overtaken by personal memoirs, of which the best known are perhaps Diana Athil’s Somewhere Towards the End, Jane Miller’s Crazy Age, and Carolyn Heilbrun’s The Last Gift of Time. But that is not enough. In The Last Gift of Time, American literary theorist and critic Carolyn Heilbrun writes: “when I accomplished sixty, I stopped wearing high heel shoes.” How interesting! But exactly where her writing stops, I would like to read more. This one sentence contains the story of how, for years, she suffered in high heels, how she walked more slowly and unsteadily with time, feeling a constant dull pain in her back. How her feet become deformed so that she could barely find a pair of shoes that fitted, and what a pleasant feeling it was to finally walk in comfort. Out of a whole range of experiences, she writes only a single sentence. Readers have to imagine the rest. By the way, Heilbrun committed suicide at the age of seventy-seven. Maybe she couldn’t stand the pressure of aging, maybe she was afraid of what was to come, or maybe she just decided to take her end in her own hands.

Indeed, contrary to all propaganda, it seems that aging isn’t great fun, and that flirting with a stranger is rarely an option.

While memoirs, biographies and diaries are considered the conventional forms in which to describe aging and old age, even there the body remains in the background. Take the American poet Mary Sarton. In her diaries At Seventy, After the Stroke, Endgame, and Encore she carefully describes her daily life and mood swings and even more carefully records changes in every rose and tulip in her garden. But not changes to her body. Yes, we read that she is tired, sleepless, without energy, but she writes about it very, very sparingly. After all, the body is not a wilting flower; the symptoms are a bit more complex, subjective and painful. Is describing your own physical aging so difficult? There must be some truth in this, because among the hundreds of writers from Sophocles up to the present quoted in the anthology The Art of Growing Older – Writers on Living and Aging, edited by Wayne Booth (1992), there are barely twenty women.

However, all is not lost. After researching more on women’s writing about aging, I got another picture. It seems to me that, although women don’t describe their own aging, they have found a way to write about it from another angle. Many write about it through describing illness, particularly dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, affecting people near to them: mothers, husbands, friends and – on rare occasions – a literary hero. And surprisingly, in writing about this topic, even novel writers reach for memoirs, autobiographies and diaries. On the Amazon bestseller list of writing on Alzheimer’s and dementia, manuals predominate, then biographies and memoirs, with only a single novel: Still Alice by Lisa Genovese.

Two well known writers, the French fiction writer Annie Ernaux, in I Remain In Darkness, and the American fiction and non-fiction writer Mary Gordon, in Circling My Mother, write on the very same topic: the mother’s Alzheimer’s and dementia. Gordon says her book is neither memoir nor autobiography and certainly not a novel. One could say the same for Ernaux. She writes a kind of diary, but not a real diary, since it gives the impression of a literary work. It seems to me to be no coincidence that both these writers decided to write about the illness of mind and decay of their mothers, why dementia and Alzheimer’s demand such attention from them, and from many other writers too, mostly women.

Loss of memory has always been connected to age, but Alzheimer’s is a new illness of longevity. As people live longer, fewer die of heart attacks or infections, and more and more survive long enough to become demented. Alzheimer’s turns into a “new social phenomena”, an epidemic, as David Shenk calls it in his book The Forgetting: Alzheimer’s, Portrait of an Epidemic. Perhaps its symptoms are the best explanation for the literary interest: the slow loss of short term memory, the loss of special orientation, the loss of the ability to express yourself and think… loss after loss after loss. With Alzheimer’s and old age in general, an individual loses body and mind. Both are degenerative processes and in fact, it is difficult to tell aging from illness.

Apart from the symptoms of physical decay, the most fascinating aspect of Alzheimer’s is the loss of memory. Memory loss is frightening because it means loss of identity. Therein lies the reason why Alzheimer’s became topical: writing about the person’s illness, a writer describes the loss of that person’s identity. Thus, while describing the advance of humiliating mortal illness, Ernaux and Gordon describe the symptoms and experience of aging as well. If, in their or any other such writing, the word Alzheimer‘s is replaced with the word old, the picture becomes clearer.

In 1978 Susan Sontag published her acclaimed essay Illness as metaphor. In it, she analyses a society and its use of an illness (TB; cancer), the way it is romanticized, moralized or turned into a myth in the literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (from Dickens and Stendhal to Mann, Kafka, Gide, Auden, etc.). Modern society is dominated by the idea that people are responsible for their own health and longevity, although the reality doesn’t quite correspond to this idea. Writing about a new illness is a more elegant way of dealing with death and dying – especially in our culture, in which death, according to Sontag, is seen as an offensively meaningless event. Yet not every illness, she writes, makes for a good metaphor. Cardiac illnesses are a sign of weakness, of a person who didn’t take care of his or her health, though are not degenerative and shameful. Cancer, tuberculosis and HIV are disgusting, shameful and humiliating in their manifestations. It seems that Alzheimer’s is the new illness that meets the criteria for metaphor and the literarization that goes with it: its cause is still mysterious, nobody is immune to it, a patient isn’t responsible for getting it and there’s no cure for it.

According to Sontag, it is through writing about illness rather than old age and death that it is “easier to understand and at the same time push further the dangerous world of death and destruction.” That is, while illness gains the status of legitimate subject, writing about aging and death are hidden behind it. It seems to me that women writers are, after all, writing about female aging, but veiling this in “modern” illnesses (dementia, Alzheimer’s) under the cover of non-fiction. In order to find such books, I had to change the word in my search engine, replacing old with Alzheimer‘s. This opened the door to a world of suffering and decay, of deprivation and immense loneliness, in which there is no flirting with a stranger, unless that stranger is a person in the bathroom mirror.