On the occasion of Europe Day, Oleksandra Matviichuk, Ukrainian human rights defender and director of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Center for Civil Liberties, delivered this year’s Speech to Europe at Vienna’s Judenplatz.

Russia as the liberal unconscious, source of all that the West finds abject and unsettling? There is something to be said for this theory, says Peter Pomerantsev in conversation with his father Igor, the émigré dissident and poet. But where does it put the myth of central Europe as ‘kidnapped West’, not to mention contemporary Ukrainian occidentalism?

Peter Pomerantsev: We are recording this conversation in Prague, where you live and where I am attending a conference organized to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of 1989, asking whether the ideals of 1989 continue to matter. We are going to discuss East and West and what has changed since ’89. Prague is a good way to start thinking about this question. Let me ask you first how long you have been here?

Igor Pomerantsev: I have been in Prague for some 26 years. Initially I worked for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. I started my radio career in London in 1980 at BBC’s Russian Service, before moving to Radio Liberty, whose London bureau got closed and whose Munich bureau then closed too. We settled in Prague upon the invitation of President Havel. I first experienced Prague and the Czech Republic as a kind of socialist ruin. When I arrived here in the 1990s, there was a mood of decadence. The people here, especially those of my age, closely resembled the homo sovieticus familiar to me from the Soviet Union.

PP: But you wouldn’t really classify Prague as eastern Europe, would you? Even in the 1990s I remember the Czechs insisting that they belonged to central Europe and getting very offended if you called them eastern Europeans. Nowadays most people would think of Prague as part of ‘regular Europe’. That begs the question of where the East is now, of where the East starts.

IP: The answer to that question has always depended on one’s perspective. People from the Soviet Union seldom visited socialist Czechoslovakia but tended to feel that the Czechoslovaks were privileged. For them, Czechoslovakia was in many ways the embodiment of the West. In central Europe, there was a strong argument that the region did not belong to the Russian cultural sphere but had been ‘kidnapped’ by the Soviet Union. In his polemical exchange with Joseph Brodsky, Milan Kundera insisted on the western origin of central Europe, which he contrasted to Russia. Since both were writers, their arguments were literary ones – they debated whether Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky could be qualified as western. The argument got quite heated, especially on Brodsky’s part. He claimed that Russian literature was the basis of European literature as a whole and asked what the ‘central Europeans’ had to show for themselves. So the two sides had a very acute sense of belonging to Europe at the beginning of the 1980s, but were also mutually condescending.1 The relationship has radically changed since.

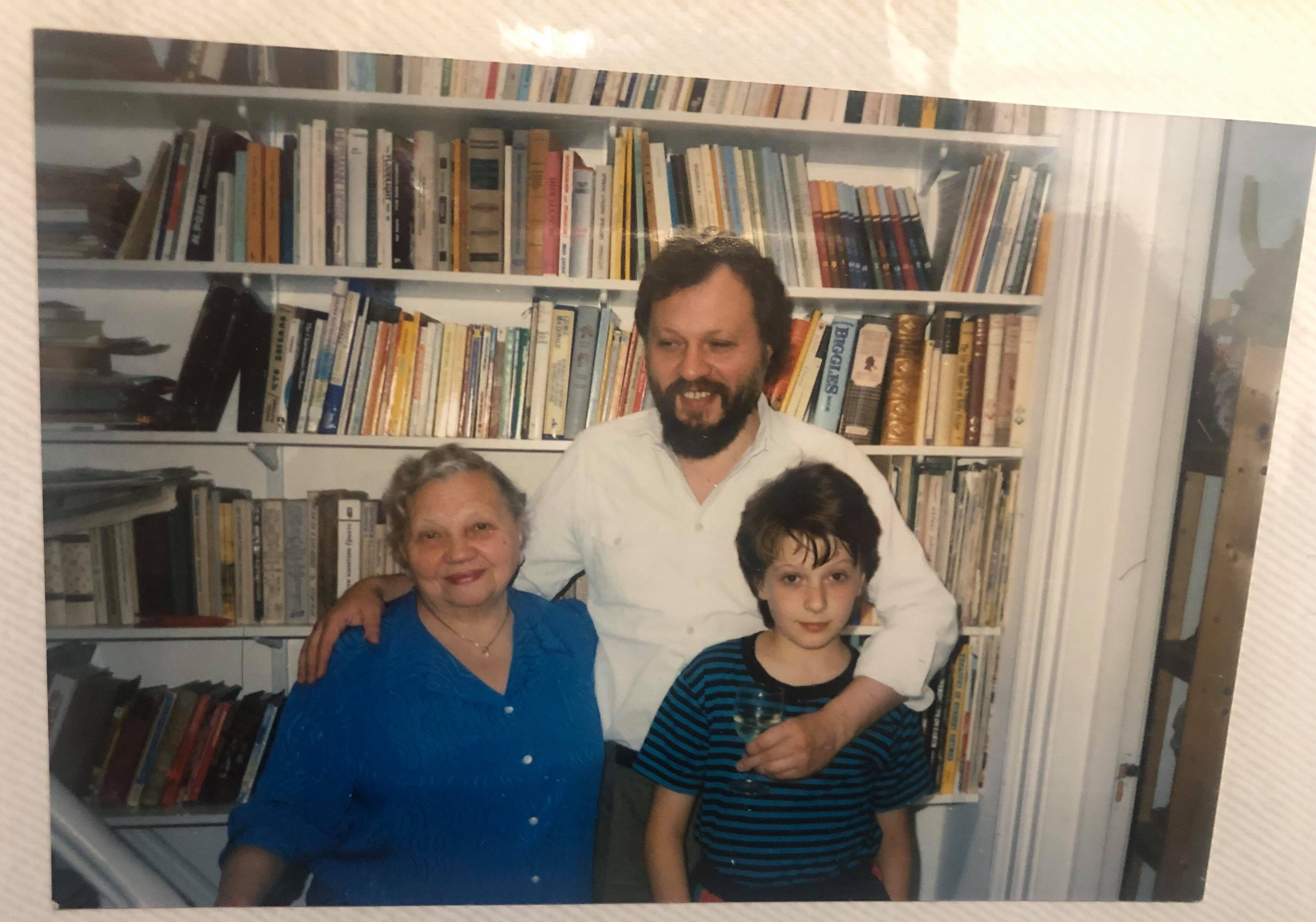

Igor and Peter Pomerantsev; courtesy Peter Pomerantsev.

PP: Radical changes also seem to be underway at the moment. In the UK – where I live most of the time – some people on the right are saying that Britain’s natural allies are going to be Hungary and Poland, which despite having ‘slightly authoritarian’ governments are confronting Brussels. Some elements are also calling for the UK to become more closely allied with Russia. So the future of Britain outside the EU could be in a new alliance with Russia, Hungary and Poland. Politically, Britain would thus become part of the ‘New East’. I don’t know whether this would ever come to pass, but it is interesting that such arguments are now part of the conversation in the UK.

The massive arrival of immigrants from eastern Europe poses one of the biggest challenges in Britain of the past twenty years. In previous decades, immigrants from the former British colonies reminded the English that they used to have an empire. Despite the social tension, the difference of the Indians and the Pakistanis, and their peculiar relationship to the English, made the English feel exceptional. But when all the Poles and Latvians turned up, they did not really care about trying to suck up to the English. Even more, there was a shock that eastern Europeans are actually quite similar: that they are football-loving, hard drinking, quite secular people. The English had a kind of nervous breakdown: they realized that they weren’t exceptional, that they weren’t all that different from eastern Europeans. Observed in this light, Brexit was a way of reacting to this horror of recognition, a way expressing that ‘no, we are different’.

IP: Moscow is now full of immigrants from Central Asia. The Tajiks or the Uzbeks are not particularly close to the Russians culturally and they tend to irritate the Moscovites, but they also confirm to them that Moscow is an imperial capital. Nowadays, Ukraine is the most hated country in Russia, largely because Ukrainian independence has profoundly challenged the Russian concept of empire.

PP: Yes, although Russia is often viewed as the East, certainly here in Prague, Russians think of Central Asia as the East. Russia can be then presented as an interesting mixed state. I was recently informed by some Ukrainian nationalist intellectuals – nationalist in the pejorative sense of the word, in this case – that historically, Ukraine was Russia’s connection to European culture and Christianity, and that now Ukraine has moved away, all that remains of Russia is a Mongolian type of regime and growing Islam. This is an intriguing theory, since it neglects all of Russia’s other connections to the West. Do you think that is indeed what we are likely to see: a Russia without Ukraine drifting further and further away from Europe?

IP: You might call it a paradox that nowadays, Kiev is the capital of the idea that central Europe belongs to the West and that Russia is practically Mongolian. This notion seems to have shifted eastwards since the end of the Cold War.

PP: As you mentioned, Brodsky challenged Kundera and asserted that Russian culture was a part of European culture. I hear the same idea from Russian liberals today. But what do Russian intellectuals and artists more generally believe? Are they still saying what Brodsky said?

IP: Yes, but Russia is a highly differentiated society. Russian culture was in fact founded by Europeans from further west, mostly by Germans – even the Romanovs were German by origin. Germans were invited to give Russia a political structure and to develop its education system. The upper echelon of Russian society was German, partly French and in a way English too, while its inner feelings and complexes were often deeply different from those of western Europeans. Russia imported western rationalism – but it also Russianized and, to an extent, perverted it. Marxism, for which there was a large market in Russia, was also taken from the West. There was an instinctive sense of connection to Marxism in Russia, despite what Marx thought about the country.

Image by Tama66 on Pixino.

PP: Boris Groys and other Russian intellectuals have argued that Russia acts as a kind of subconscious for the West: as the place where western fears and fantasies play out, but which also functions as a distorting mirror that consciously takes on the role of the unconscious, so to speak. This idea is quite prevalent today: Russia as the edge of the West, where western ideas are played back in grotesque form. So are our ideas of ‘East and West’ just a diplomatic way of referring to the mutually reinforcing relationship between Russia and everything that is west of it?

IP: I will speak as a writer. I believe we should be speaking not so much about East and West as about deep psychological phenomena like life and death drives. There are cultures where the death drive is stronger: just think of the Aztecs. Of course, such cultures can possess great aesthetic value and may have their heroic aspects. But the history of the twentieth century provides very strong evidence that this instinct is dominant in Russia as in few other countries. Russians have killed themselves, each other and other people millions of times over. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, in his classic novel Cancer Ward,2 found here a formula that is much stronger and more devastating than Reagan’s ‘evil empire’ – an expression that I believe Reagan took from C.S. Lewis. What is the meaning of Cancer Ward? Cancer exists at the expense of life textures and expands to the west but also to the east and the south. If we took this metaphor seriously, we could think of Ukraine as a country with an instinct for life: Ukrainians today do not want to be part of the cancer ward – most of them instinctively reject the idea of dying.

Igor and Peter Pomerantsev with Igor Pomerantsev’s mother, ca. 1988. Courtesy of Peter Pomerantsev.

PP: I am aware of the idea of Russia as a suicidal culture. Other cultures have perpetrated genocides too, but self-destruction seems to be dominant in Russian society and culture in a rather special way. But let me get back to my previous point: is the duality of East and West just a way of talking about Russia’s cultural relationship with everything that is west of it? I must admit I don’t agree with all the articles that have come out in recent years arguing that western attitudes towards Russia are Orientalist. Orientalism presupposes a colonial relationship, whereas Russia is a partner in this relationship, and quite happily takes on the role of ‘the Other’. It articulates and exploits that position – it is far from a passive recipient of external narratives. Russia, especially Russian political elites, even delight in being the other.

It is very interesting to observe how Donald Trump gets associated with Russia. I am not talking about the Russian operations to support his election campaign but about the cultural discourse around the Trump phenomenon. The words ‘Trump’ and ‘Russia’ are joined in many people’s imagination and that is often how he gets contextualized in the media. Trump is, of course, a creature straight out of the cultural unconscious – in his use of language, in his sexual desires, in his breaking of all kinds of norms, rules and the symbolic order. In his reality shows, he acted out the fantasy that anybody can become rich. The fact that he immediately becomes associated with Russia seems to be a way for western societies to make sense of the place he comes from within western society.

There is a very good novel by the Russian writer Zinovy Zinik called Sounds Familiar or: The Beast of Artek, about how, during the Cold War, Russia was a luminous and perverse ideal for a certain type of leftist.3 Zinik tracks these leftists during the 1990s, when Russia became their nightmare. They develop the idea that Russia is where hell comes from. We see this attitude in parts of the western left today, which has gone from an absurd adulation of the Soviet Union to connecting Russia with everything that is malign.

IP: What is shocking is that during the past hundred years, Russia has twice become the leader of destructive forces. You can go even further back. In the nineteenth century, Russia was the ideological leader and most powerful member of the anti-liberal Grand Alliance. Russia may have changed ideologically, and may even have forgotten ideology, but it once again wages hybrid wars – only now in a cynical way, aiming to morally undermine the West. Such projects always have their allies in the West – whether in the US or in Europe. The Czech president Miloš Zeman even speaks about Russia as if he were its foreign agent. The regime in Hungary also has instinctive affinities with Russia. In Austria, right-wing parties found a mutual language, not to mention common financial interests with the Russian regime. The US President is evidently a sympathizer, even a fan of the Kremlin. Russia plays a colossal destructive role, not by opposing communism to capitalism, but by propagating a cynical attitude towards politics, in an attempt to undermine democratic institutions and structures.

PP: There is also a self-destructive impulse behind Donald Trump and all the obsessive focus on him. The same goes for Brexit. Take the catchphrase ‘take back control’, the slogan of the leave campaign. Any psychoanalyst will tell you that it is a classic phrase used in self-harm: anorexics who cut themselves and people who attempt suicide always talk about having lost control; self-harm or even self-destruction is the way they can restore this. There is clearly too much anarchic, self-destructive energy in politics at the moment. With self-destruction being ascendant, does this favour Russia? Is this truly the only way Russia can define its role in its relationship with the West? Is there any way the relationship could become healthier and more productive?

IP: I believe the balance between constructiveness and destructiveness has remained fairly stable across the centuries. This confrontation persists. It may be impossible to provide an exact balance sheet between the two. For me, the idea of literature and art is that divine destiny pauses death: art continues to flourish after the physical life of the artist. This is my duty as a writer, and it is the duty of all those who prefer creativity and constructive activity. You could say that writing poetry is my personal position regarding death.

See esp. Milan Kundera, ‘An introduction to a variation’, New York Times Book Review, 6 January 1985. Joseph Brodsky, ‘Why Milan Kundera Is Wrong About Dostoyevsky’, New York Times Book Review, 17 February 1985.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Cancer Ward, trans. Rebecca Frank, New York: Dial Press 1968.

Zinovy Zinik, Sounds Familiar: Or the Beast of Artek (London: Divus, 2016).

Published 17 December 2019

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Peter Pomerantsev / Igor Pomerantsev / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

On the occasion of Europe Day, Oleksandra Matviichuk, Ukrainian human rights defender and director of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Center for Civil Liberties, delivered this year’s Speech to Europe at Vienna’s Judenplatz.

Whether defending human rights on an international stage, checking facts from the frontline, processing traumatic experiences over a lifetime, or even questioning the language you have spoken since childhood – all matter in the collective fight for justice.