‘Quit speaking to the centre’

‘You watch TV, you open a magazine, you see billboards, and you never see yourself.’ A conversation with Hungarian Roma LGBTQ+ activist Joci Márton on minority representation in Europe and how minority members themselves can take the lead.

Lore Gablier: Representative democracy is based on the idea of citizen participation. While it is a model that has enabled the inclusion of a multitude of voices long excluded from the public sphere, it is also far from perfect. What are your thoughts on this? What does it mean for you to be represented and how does it relate to being present?

Joci Márton: It is possible to be present but not being represented. I think this is the experience of many of us who belong to a minority group, especially when you belong to an intersection just like me: I am a Roma man who happens to be gay. Growing up as a Roma, I never felt represented. You watch TV, you open a magazine, you see billboards, and you never see yourself. It feels like you simply don’t count.

In Hungary, we are completely out of media representation and yet we are 10% of the population. If you talk about Europe: we are 10 million. There are countries that are smaller, so we should be really more of a factor. That’s why I felt the need to focus on the representation of Roma LGBTQ communities.Together with them, we produced photos and video material. I chose to name the project ‘Owning the Game’, which refers to the question of self-representation.

Listen to Joci Márton in conversation with Lore Gabriel on the European Pavilion Podcast.

LG: Raising the issue of representation and the lack of it also invites us to consider the importance of self-representation. Could you elaborate on this notion?

JM: For me, self-representation means that we are now the ones who decide what we are going to look like in pictures and videos in the public space. When we talk about the lack of representation, we also need to mention the bad representation that comes from the fact that we are not the ones who lead the way we are portrayed. And it’s not just about Roma people. Think about women: we can’t say that women lack representation, but unfortunately, their representation has historically been led by men.

Self-representation from a minority point of view is almost impossible. I often feel that I can’t get rid of the conception of the people of the majority. Many times, when we would like to talk about ourselves, we realise that we are seeing ourselves through a majority glass. This is what we need to consciously get rid of. One of the ideas at the beginning of my project was to decrease the stereotypes against my group. But then I realise that, if I went continuously against the stereotypes, there would be no space left to speak about myself. It is thus really important to distinguish between decreasing stereotypes and self-representation. They are both important but they need to be distinguished.

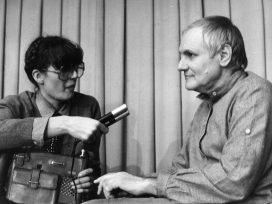

Joci Márton representing himself. Photo: András Jókúti. Stylist: Anett Gálvölgyi & Márton Miovác: Hair stylist; Márk Károlyi. Make up artist: Tímea Vozák. Courtesy of the European Cultural Foundation.

I think that the politics of representation are also connected to media representation. For example, when it comes to talking about Roma issues, there is no media representation, so there is no one to remind the majority to address these issues as well. The people of the majority have to influence politicians and check what they are doing for Roma communities. When you have a voice in the media, you can raise awareness of political realities. That’s why I feel that more Roma should talk to the people as well as to their communities. When you look at how the government is built up, and by whom, you don’t see Roma people. It’s obvious that decision makers cannot represent our interests, and this needs to change.

I feel that nowadays, thanks to social media, our society became a little bit more democratic. On social media platforms, young Roma people have started to be present and their followers are mostly their Roma peers. I can say the same about people with various disabilities: they also found a way to reach their public through social media. But it doesn’t change the fact that we are excluded because it is the mainstream media that has the power to make you count. All the acknowledgement goes to the inventive young minorities who try to make the most of the available tools. But I also feel like we are creating little ghettos online. At least, we can claim a little platform, but it’s not something that we can be satisfied with.

LG: How should we approach the question of representation from the perspective of Europe?

JM: I have a European identity. But I often feel that Roma people can only feel this if they travel. It’s really hard to feel this European identity and togetherness if you have never left the place where you live, when you don’t speak languages, when you don’t have friends from other countries. That’s why, when there is a political party advertising itself as European, I feel like they’re talking to me because I am a middle-class man who has travelled and seen the world. But what about people who don’t have the same response? For me, it’s really interesting to think about how other people can be involved in this Europeanness: how they can feel it.

Europe is more than a collection of nation-states and it needs a different story to engage with its future. The European Pavilion project looks into potential representations of Europe with its podcast series serving an artistic investigation.

LG: In your imagination, what could the European Pavilion look like and what shall it address?

JM: I imagine it in a way that is really inclusive. I imagine that it is going to be more a mirror of real society. We tend to think that the representation is a mirror of our society but it is not: so many people are not represented. I would say that the European Pavilion should be brave enough to bring up topics that we don’t want to discuss. When I say that we need to be brave, I mean that we need to stand for our values. If we really think of human rights and democracy, we need, as we say in Hungarian, to quit ‘középre beszélni’, or ‘speaking to the centre’. We need to take a stand. That’s what I would like to see.

This article was originally published by the European Cultural Foundation and the European Pavilion Podcast, and republished in Eurozine within an ongoing collaboration with ECF.

Published 17 December 2021

Original in English

First published by The European Pavilion Podcast

© Joci Márton / Lore Gablier / European Cultural Foundation / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Under the commercial imperative of ratings and likes, public service broadcasters are moving complex and quality content to online only. As the example of Germany’s Westdeutsche Rundfunk shows, this fragments audiences, thereby undermining a core principle of public service.

Even though socialist internationalism was the official ideology in communist Hungary, popular media at the time was teaming with nationalist narratives, hidden in plain sight. What does this contradiction explain about today’s politics?