Jonathan Swift was an Englishman who lived in Ireland and who, from a certain point of view, took Ireland’s part. He suggested the Irish should burn everything English except their coal. Swift had many hatreds. For example he hated lawyers, but admitted it was the tribe rather than individuals that he despised. I think he felt the same way about dentists. This is not unlike the Irish attitude towards England. The Irish, or at least a fair few of them, have a problem with England that they can’t quite shake off. Well actually they don’t really want to, not yet anyway. But that is not to say that many of both sexes would not be more than a little happy to spend an evening in the company of Miss Elizabeth Bennett, Dr Johnson or some other English figure of their choice.

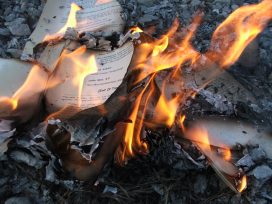

In pubs quite a few cheer for whoever is playing against England and in polite circles the fashionable term to describe the feeling generated by Brexit is schadenfreude, which means a mean-spirited delight in another’s misfortune but sounds sophisticated and, even better, European. As we await, with thinly disguised pleasure ‑ albeit tinged with fear and terror ‑ what we imagine will be a latter day fall of Constantinople across the Irish Sea, we are in a fundamental way mystified. Why are the cunning Brits doing this? Is it idiocy or is it something else? Do they know something we don’t? But actually Brexitry arises from the same source as Irish glee over the prospect of our near neighbour, John Bull, falling from his ladder. It arises from historical experience. We know plenty about our own historical experience. Maybe it’s time we paid some attention to England’s. After all, when the English move away from the EU, their island will not be towed out into the mid-Atlantic. They’ll still be next door and we’ll still be watching their historical dramas and their football. It would be as well to understand what makes them tick and we may as well start with the Reformation as this year sees the 500th anniversary of the theses-nailing episode in Wittenberg.

There was once a story told in England of the Reformation which was very popular for a very long time. It featured decent sixteenth century parishioners increasingly uneasy over clerical abuses, fat friars, insufficient prioritising of the Bible and, of course, Roman glam and frippery. Pressure mounted in the shires. Something had to be done! And in this telling, Henry VIII ‑ who did something ‑ did not destroy an existing and long-established Christian church in the service of his personal and political interests but rather responded to the national mood. Good old Henry!

Without being overly reductive it might be noted that this exceptionalist story of the Reformation in England and of an English separation from Europe chimed nicely with the centuries of successful imperial expansion which followed. There was a clear advantage ‑ one which crystallised over time ‑ to casting off the integrative trappings and trammels of European Christendom. If you were going it alone, the Roman miasma would only hold you back, tie you into the small stuff. Clear blue water between England and the rival empires of France and Spain aided the nation’s faith in her exceptional destiny. With a national church you could do stuff easily, no need to seek Rome’s blessing or permission. It was more efficient, more conducive to maritime glory and empire. And indeed it was.

From the late seventeenth and through the eighteenth centuries as Britannia triumphed, this evolving version of the Reformation in England was rinsed in the rigorous waters of intellectual Whiggery, and not just by the Whigs. Continuous washing and ironing of the past, aided by useful bits and pieces of Enlightenment thinking, saw the emergence of a radical new model of human development, one which rested on a particular idea of progress and which was conducive to the permanent expansion of English power. In this vision of a divinely sanctioned pilgrim’s progress “from this world to that which is to come”, the Reformation was celebrated as being in the magnificent tradition of the Magna Carta, a logical precursor to parliament, the glorious revolution of 1688 and all the human wonders which followed. Thus the concepts of liberty, the individual and duty came to replace those of ritual and sacrament, and in the new order Anglicanism’s ceremonies would be in unambivalent service to the imperial path, a path which ultimately served the interests of all humanity.

But recently dissident historians operating from deep within the English academy have been busy undermining the traditional account of the Reformation. Eamon Duffy of the University of Cambridge has been prominent among the revisionists. Duffy carries a bright torch for the recusants and traditional English Catholicism. His The Stripping of the Altars and other works have pretty much conclusively established that the pre-Reformation church was in rude good health and that the ordinary faithful did not at all welcome the new religious order which, as the Catholics always said, was a top down-affair.

There was once a different time in England, a time when promoting Catholicism was unsafe. In the late seventeenth century, for example, Archbishop Oliver Plunkett was tried in Dundalk ‑ which, as it happens, is Professor Duffy’s birthplace ‑ for the crime of promoting the Roman faith. He was taken to London, where he was hanged, drawn and quartered. In sentencing Plunkett, the chief justice, very much on message, remarked that there was nothing more pernicious to mankind than promoting false religion. Well, there you have it! The world would have to be saved.

Anti-Catholicism became a core feature of English identity as the glories of its maritime empire grew through the eighteenth century. Paganism wasn’t much liked either. Whether In Ireland, America or India the natives’ attachment to false religion allowed the business of empire to proceed without scruple.

It could be argued that giving the recusants their historical due is a contemporary adjustment to the collapse of England’s empire and world dominance. But this is perhaps overly simple. Historical revisionism in this area does not challenge belief in English exceptionalism, a phenomenon at the centre of English culture and one which over time has trumped all others, including anti-Catholicism. As the expansionist dynamic adjusted to economic, technological and political developments it became less dependent on anti-Catholicism, which in time became ideologically redundant, though it was never entirely discarded. The English monarch, for example, is still prohibited from marrying a Catholic. Notwithstanding cultural survivals, the English have been moving away from visceral anti-Catholicism since, at least, the early nineteenth century in favour of the science and morality of free trade and gunships. Religious divisions among peoples, it was found, could usefully be exploited to divide potential adversaries. And anyway wasn’t there something intrinsically Protestant about freedom of conscience?

By the early decades of the nineteenth century anti-Catholicism was quite passé in fashionable circles. With France and Spain defeated, Catholicism was no longer an existential threat but rather something which could easily be managed both in Europe, at home and elsewhere. Indeed converting to Catholicism began to have a certain cachet, a suggestion of intellectual seriousness and depth, a prestige which has continued to adhere to it into the twenty-first century. From around the 1830s, significant sections of the English literary, philosophical, religious and artistic intelligentsia took off on a spiritual quest to rediscover the aesthetic and spiritual pleasures of medieval Catholicism. Here, indeed, was a dragon without teeth, no longer to be feared. Professor Duffy need not listen fretfully for the sound of military boots crossing the courts of Magdalene College. No one has really cared for a long time. The rehabilitation of English Catholicism could well have happened earlier. Catholic counter-history was always available. Perhaps what was missing was a historian with Duffy’s brilliant command of the sources.

Free trade did not require enthusiastic Protestantism and as the nineteenth century progressed the ideal of international proselytism faded in the centres of English power. Religious freedom was acceptable just as long as people purchased from the workshop of the world. By the mid-nineteenth century over half the English population did not attend church on Sunday and around this time the Irish began to refer disparagingly to “Pagan England”. One can only imagine what English sophisticates made of their Protestant kin in Ireland still remorselessly flogging the sickly equine of seventeenth century anti-Catholicism. Their successors today are those urban sophisticates appalled by the DUP and mystified to find it is an integral part of Westminster governance.

For devotees of Manchesterism, free trade was understood as the engine of social development, a phenomenon as natural as gravity and one which only inferior minds would challenge. Those who resisted free trade were backward people, ignorant of history’s processes and, also, of the natural hierarchy in human affairs and their own, probably quite lowly, position in same. Sometimes a big stick was needed to bring recalcitrants into line. But in the end it was for their own good! Thus in 1839, in order to open up China to trade in narcotics ‑ trade is trade! ‑ the Royal Navy, with the aid of its advanced gunships, initiated the Opium Wars which forced that very out-of-date civilisation to embrace the virtues of opium and by way of penalty hand Hong Kong over to London. David Cameron and Michael Gove, some years after Hong Kong was returned to the Chinese, were outraged when on a visit to China in November 2010 they were asked to remove their poppies, which were seen in that country as a symbol of Chinese national degradation during the Opium Wars. As good exceptionalists, they refused, citing their commitment to political freedom. That was when the West still believed capitalism couldn’t function without parliamentary democracy. Post-Brexit, as the UK, or what’s left of it, seeks trade deals with the massive Chinese economy, its representatives may decide that it is prudent to ditch the poppy. Unfortunately, the problem with the Chinese is that they have long memories. Actually, they’re not the only ones: the Indians are a bit like that too.

The very successful English nineteenth century reinforced the culture of exceptionalism as the stock in trade of England’s take on the world. Even the somewhat disconcerting emergence of the US as an international power could be explained as originating in its English foundation. But Yankee power was a harbinger of trouble ahead. The twentieth century was a much rockier experience for the English. It transpired that there was to be an end to the country’s run of luck and that there was a limit to the political prizes a small island off the Eurasian land mass could accumulate. (A number of relatively small but highly ambitious states were to learn a similar lesson in the course of the twentieth century.) The US then played Rome to England’s Greece and stamped its brand on the twentieth century, without too much deference towards the old country. From an objective point of view it was all over.

It is possible that, for England, the twentieth century could have seen the gradual disassembling of the empire, its trappings and its culture of exceptionalism under the relatively benign oversight of the US. English realism and pragmatism are deeply ingrained administrative and cultural habits. The signs that England was willing to move on were numerous. But that is not how it turned out. Seminal events of the twentieth century, in particular the two world wars, deferred the island nation’s appointment with reality and had the effect of breathing life into the traditional notion of England’s glorious destiny, its splendid and superior isolation.

Returning to the early twentieth century, the explosion of German productive power, which left Manchester and the midlands behind, was a major challenge. Arguably, a deal dividing the spoils could have been done with Germany and a Europe, under the hegemony of the German and English cousins, might have coalesced against whatever was to arrive from the east or elsewhere. Britain might have been involved in leading a united Europe. But that would have been asking too much of pragmatism. Centuries of manoeuvring for a divided Europe and plotting against European powers could not easily be forgotten. England stuck with the old impulses. The new enemy of civilisation became known as Prussian militarism and later, what came to be seen as its close relative, Nazism. With US assistance, the Germans were routed twice. Protestant Prussia, once England’s ally against Napoleon, was removed from the map and discontinued as a political entity. The victory seemed total. It is interesting that poor Theresa May, in her lamentable efforts to gain advantage in the Brexit talks, has relied on the old impulse. Of course the EU27 saw her from a mile off and her efforts to divide have come to naught.

Obviously England in 1945, though something of a US vassal, felt pretty good about winning and their victories were cast in the available language of exceptionalism: Standing alone in 1940, Spitfires piloted by brave toffs with silk scarves flowing (what Poles?), the island people surviving and eventually triumphing against the evil of Nazism. The fact that the Nazis represented an unprecedented interweaving of the darkest threads in European history lent the story of England’s resistance an undeniably heroic dimension. It was feelgood stuff, but it was not the stuff of geopolitical modesty and it distracted English society from necessary adjustments in strategic outlook. The Suez overreach a few years later provoked a stiff kick in the rear from the US, the new world power. Victory made slow learners of the English.

The pragmatic element in British society did not entirely disappear. In the economically sluggish 1960s and 1970s, criticism of anything touching on the 1940s was taboo but some had a go at the mechanised slaughter of the Great War, the 1969 film Oh! What a Lovely War being one of the most effective. With Labour mostly in power at that time, decolonisation was widely accepted, with Harold Wilson refusing to send British troops to Vietnam and, EEC membership from 1973, it might have seemed that Britain was finally making the historically necessary adjustments to its understanding of itself in the world. But this did not happen.

The sixties and seventies were a period which saw the power of trade unions at its zenith. But neither trade unionism nor its political wing was to save the nation; there were endless slogans but no convincing vision of a new future for the country. Explaining this failure ‑ one which did not mark a fair number of European Social Democratic parties ‑ is probably a complex business. But at least part of the explanation may rest with the simple fact that Labour was implicated; it did remarkably well out of imperial free trade and has long been embedded within the culture of English exceptionalism. In the end, Labour was the party not so much of national vision as of fair play and a palatable class system. It was, and remains, the party that closes its annual conferences with throaty renditions of the patriotic and exceptionalist hymn Jerusalem.

The property-owning classes, demoralised by trade union power, girded their loins and responded to what had become a political stalemate with an enthusiastic reassertion of their political commitment to free trade and insistence that the working classes got back into their proper place. This Conservative Party revolution led by Margaret Thatcher was going to make Britain great again and, for many, it looked as if that was exactly what was happening. It was an exciting time and the cloth caps took it in the neck. It is hardly surprising that Thatcherism was accompanied by a reassertion of the culture of exceptionalism. Again the focus was on twentieth century military victories. Poppies, Spitfires and crushed Nazis in their amazing uniforms and tanks were everywhere. When the French hosted Thatcher at the celebration of their revolution’s bicentenary, an event they regarded as of immense importance, she left them in no doubt that she saw it as quite minor and malign in comparison with England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688. Post-communist eastern Europe adored Thatcher, who was also regularly in and out of the White House. Here indeed were a special people, as those pesky Argentinians on the Belgrano were soon to learn.

But there was a little problem, actually a big problem. While Thatcherism was a rhetorical success it was not an economic success. The wealth of the country was not transformed. The old problem of relative economic decline continued. The rhetoric rested on rhetoric. It took a while for that to have a political effect but it did come.

In the end the English got tired of Thatcher and shortly turned to Tony Blair, whom Thatcher described, significantly if somewhat creepily, as her greatest achievement. Old Labour had failed to step up to the plate in earlier years; what was New Labour to do? Blair upped the rhetoric to unprecedented heights. The world was entranced by his mellifluous tones, his bright eyes and bushy tail. It seemed that there must be something fundamentally transformative under way. But when the honeyed words settled over the land it was possible to see that what was under way was a reversion to the status quo ante, a version of English one-nationism whose origins went back to Peel and the repeal of the Corn Laws in the 1840s. It was a return to English fair play, which Thatcher in her anger at trade union spoiling had rejected.

Certainly it was more traditionally English than the anti-working class extremism of Thatcher, exemplified in her ruthless smashing of the miners and her failed attempts to introduce a poll tax. But that anti-working class stuff had run its course by the time Blair arrived. The unions were emasculated and, once again, it would be good old-fashioned fair play from above as long as it didn’t interfere with the economy. And that is what Blair did: he restored fair play without interfering with free trade nostrums. And, of course, he too was an English exceptionalist. As he bowed out of politics in 2006 he declared “This country is a blessed nation. The British are special. The world knows it. In our innermost thoughts, we know it. This is the greatest nation on earth.” For good measure a year later he “swam the Tiber” and was received into the Catholic church.

In 2002, Blair’s key foreign policy adviser called for a new kind of imperialism, one which would bring order to the world. Senior Labour Party people objected and there was a fear that intervention in Iraq was being contemplated. The mass protests against the possibility of invading attracted between one and three million protesters in London, which is said to have been the largest protest in the city’s history. The war, which was a bloody and murderous disaster, went ahead regardless. That which progress demanded, it seems, would be undertaken by those whose duty it was. Significantly, the vast numbers who objected did not insist. Remarkably, Blair’s disastrous war did not come with much of a political price. Labour remained New Labour.

There was a far-reaching political truth lurking in this. Many of those who partook in that massive protest probably voted Remain in the recent referendum on EU membership. But, as with the anti-war protesters, the 48 per cent who voted to stay in the union appear to be utterly without political coherence or confidence. They cowered as they were denounced as citizens of nowhere. Half the population has rolled over. It is quite extraordinary. Brexit is regarded as a done deal. Even the opinion pieces in the anti-Brexit Guardian are becoming resigned to accepting what is termed “the will of the people”. Remember the poll tax protests: there is nothing like that coming from the Remainers who, it seems, are politically unable to challenge the culture of exceptionalism, even in its most nationally damaging and decadent manifestation. Perhaps it is because exceptionalism is also a goodly part of what they are.

A hard exit may yet be stopped by a collapse of the government; certainly it shows no sign of being stopped by popular protests. One conceivable means in the present parliament would be a cross-party alliance of pragmatic exceptionalists demanding a fudge. They could, for example, insist on a five-year transition period, an idea towards which the DUP and its beef-farming supporters are favourably disposed. A five-year transition could be presented as a stepping stone, the freedom to achieve freedom as it were. In that five years Mark Garnier or his successor in international trade might have to reluctantly report back that the empire’s former subject peoples are not rushing back to Mother. It could, just possibly, be the means which would allow England to tiptoe away from its toxic political heritage and become a team player. In that event it might be hoped the Irish would lend support and encouragement. After all, it’s nice to get on with your neighbours, lending a ladder or lawnmower every now and then, even when there have been issues about overhanging hedges and the like.