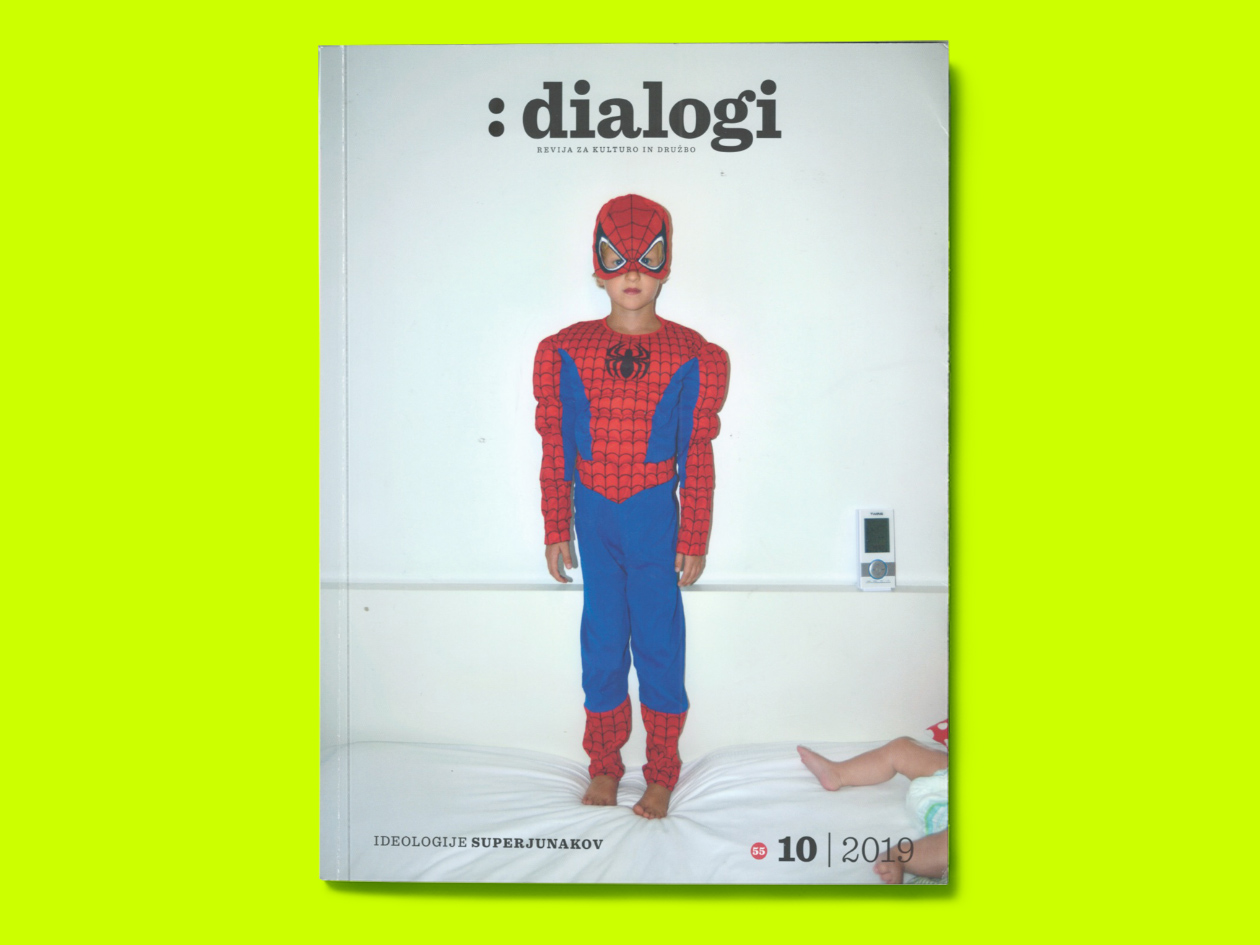

Dialogi analyses superhero narratives East and West: from Slovene romanticism to post-communist spoof and the neo-con blockbuster.

The combination of digital technologies and the need for new heroes after 9/11 has increased the popularity of superhero films globally. Introducing a dossier on the subject, Dialogi’s film editor Matic Majcen argues for a better understanding the ‘deeper ideological underpinnings’ of superhero films, with their portrayal of ‘the struggle for absolute good’. As a ‘prominent ideological apparatus of American popular culture’, he writes, it is hard not to be influenced by their narratives.

National heroes

‘Superheroes’ played an important role in forming Slovenian identity during the Spring of Nations and have maintained their iconic status to this day, writes Majcen. Three obvious candidates in the Slovenian folk and literary tradition – Kekec, Peter Klepec and Martin Krpan – lack the qualities defined by Jess Nevins (an authority on pulp fiction) as being characteristic of full-fledged superheroes: for example, a superpower, dual identity and a codename. Instead, they can be described as proto-superheroes who serve ‘ideological purposes’ – namely the preservation of the status quo.

Soviet supermen

Natalija Majsova analyses the superheroes of late Soviet, post-Soviet and contemporary Russian cinema. Soviet-Russian heroes’ ideological functions have changed and adapted to different contexts: ‘While rare and low-budget post-Soviet heroes tended to be clumsy and humorous, inhabiting expressionist, unstable worlds, the heroes of the past fifteen years reflect a state policy that aims for a nationalist consolidation of the cultural imaginary, and for a justification of the absolute power of state structures.’

Like their American equivalents, Russian superheroes underwent thorough transformation at the beginning of the twenty-first century. A good example is the tongue-in-cheek film Chyornyy frayer (1999), featuring an urban vigilante, dressed in black and indifferent to social values and hierarchies. In Putin’s Russia, however, superheroes are required to know their place. Unlike the ancient Slavic characters who worked with the state for the common good, the Russian superheroes of the present are expected to restrict their powers to the private sphere. Official Russia needs superheroes only ‘when fighting for small everyday victories’, leaving good and evil ‘to the more skilled structures of national government’.

Handke

Boris Vezjak approaches the Handke controversy through the analogy of a pizza: should one only care if it tastes good and not worry about the morals of the chef?

More articles from Dialogi in Eurozine; Dialogi’s website

This article is part of the 1/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our reviews, and you also can subscribe to our newsletter and get the bi-weekly updates about the latest publications and news on partner journals.

Published 28 January 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

From a childhood where fraternity rites were common to playing the lead role in a film about gay love: how a heterosexual, Roma man — a father of three from a traditional community in Ploiești, Romania — overcame his reservations and inhibitions about challenging the masculine norm on-screen.

A key country

Osteuropa 4–6/2021

Osteuropa focuses on the ‘key country’ of the Czech Republic: with articles on the state of democracy and the transformation of the party system as mirror of wider processes. Also, an overview of a thousand years of religious history, and the new-old national self-image in film.