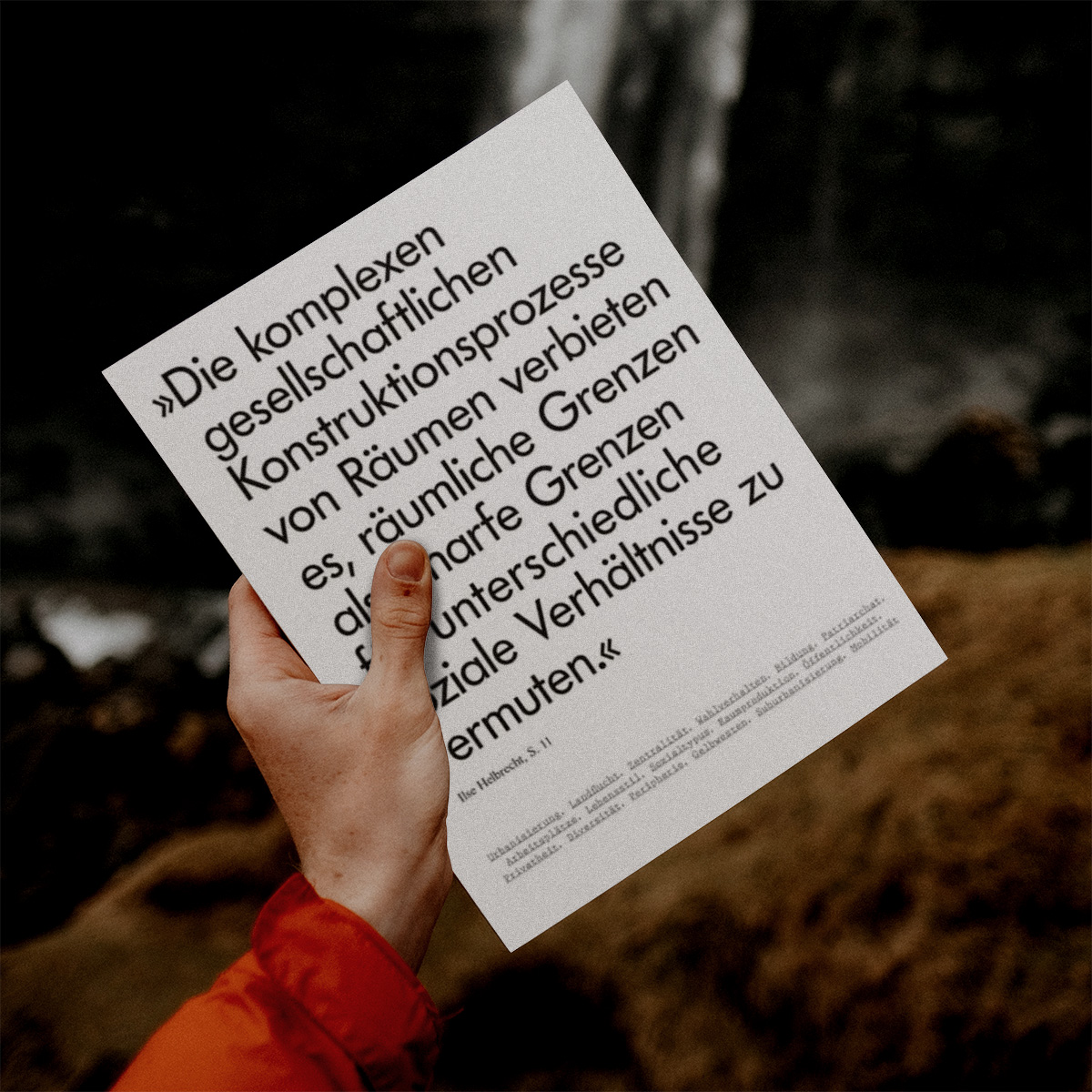

The re-politicized dichotomy between ‘town and country’ may, on closer inspection, be less rigid than we think, remark the editors of the urbanist magazine dérive. The observation is borne out by Maximilian Förtner, Bernd Belina and Matthias Naumann, who analyse support for the AfD in terms of Adorno’s definition of education (Bildung) as ‘de-provincialization’. Their comparison of three different constituencies in eastern and western Germany suggests that the dynamics of town and country are variously filtered through processes of urbanization, socio-economic transformation and peripheralization.

Like other parts of north-eastern Germany, the town of Greifswald in western Pomerania has suffered from the collapse of the agricultural sector since 1989. Here, the reaction to urbanization and the transformation to a service-sector economy has been one of right-wing ‘ruralism’, in which pre-urban structures are reproduced. In the Schönau district of Mannheim, in the opposite corner of Germany, a different effect can be observed. This is a disadvantaged area with high levels of social housing and a thirty-year history of rightwing violence. Here, ruralism replaces reflection on resentment towards ‘the other’. Finally, in the Heidach district of Pforzheim, also in south-west Germany, where the population is between 80 and 90 per cent Russian-speaking, support for the AfD is a ‘local reaction to global urbanization and social-spatial segregation’.

Austria

Historical voting patterns in Austria still fall along a distinct town-country axis. As psephologist Günther Ogris explains, urban regions, above all Vienna and Linz, continue to vote predominantly social democratic, while the rural remainder of the country votes conservative. This picture has been complicated in the last decade by the rise of the far-right FPÖ in the formerly conservative states of Upper Austria and Styria: ‘What used to be said about the industrial cities, also known as the Austrian rust belt, i.e. that they vote FPÖ, suddenly happened among the rural population.’

Sebastian Kurz’s verbal attacks on Vienna – that the city is dangerous, that its residents are lazy and abuse state benefits – likewise belong to a long tradition of enmity between the provinces and the capital. Despite being kept in check by a succession of grand coalitions, the narrative is kept alive because the working class in Vienna has a large immigrant component. ‘The anti-proletarian reflexes of the rural middle class thereby acquire an additional xenophobic touch. That was also the case back in the days of the monarchy.’

This article is part of the 14/2019 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our reviews, and you also can subscribe to our newsletter and get the bi-weekly updates about latest publications and news on partner journals.

More articles from dérive in Eurozine; dérive’s website