The meaning of Mark Rutte

The Netherlands is set for elections. Despite the current Dutch prime minister’s many problems, from the COVID-19 pandemic to a childcare benefits scandal, there is talk of him winning a fourth consecutive term. But who exactly is the man behind a decade of leadership?

When Mark Rutte took office as prime minister at the end of 2010, he joined the ranks of right-wing conservative male government leaders, who at the time were the face of European politics. In the UK, the coalition of the Tories and Liberal Democrats had just begun under the leadership of David Cameron; in France, Nicolas Sarkozy was just over halfway through his first (and only) term; and a year later, in Italy, Silvio Berlusconi’s fourth (and last) term came to an early end.

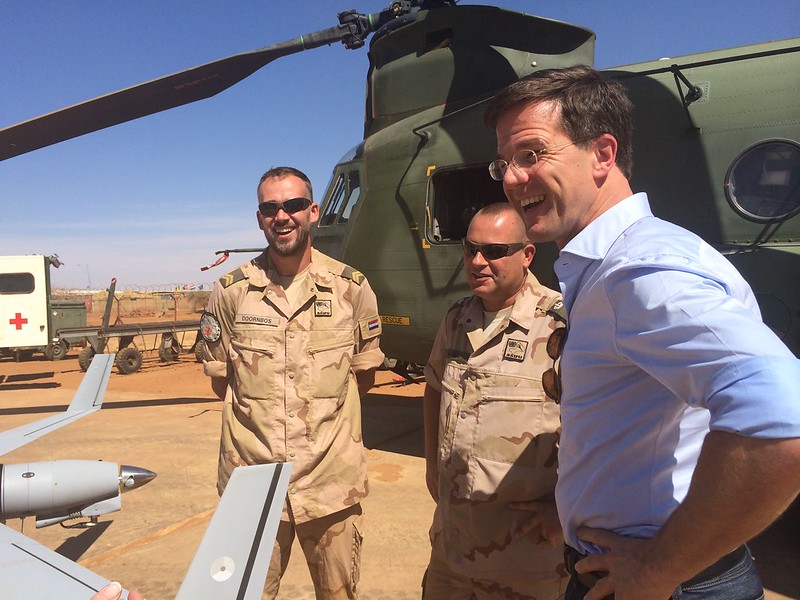

Photo by Maarten from Netherlands, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

At a time of growing economic misery, this dominance of right-wing government leaders led to some confusion among many political commentators. Shouldn’t the crisis have blown wind in the sails of the Left? Elsewhere in Europe this led to a discussion about what this right-wing wave said about the times and what its leaders symbolized.

In the UK, for example, Richard Seymour’s The Meaning of David Cameron sought an answer to the question of how David Cameron, as leader of the Tories, had managed to go into the elections as a (seemingly) progressive candidate.1 The book was partly inspired by Alain Badiou’s The Meaning of Sarkozy and his examination of Sarkozy’s ideological project, which he describes as a form of ‘dark and ruthless conservatism’.2

Quite a number of books about Mark Rutte have been written already, but they hardly seek explanations for his success or attempt to understand the ‘meaning’ of his success and what it says about his period in office (2010–present). In contrast to the aforementioned leaders, Rutte recently celebrated his tenth anniversary in power and could even become the longest-serving European head of government in recent memory. Despite the resignation of his third cabinet because of the child benefits scandal (the Dutch tax office accused thousands of families of claiming child welfare payments fraudulently between 2013 and 2019), Rutte still stands a good chance of winning the next election.

Of Rutte’s contemporaries, only Angela Merkel and Viktor Orbán have been in power longer. In Orbán’s case, that success is due to his rapid dismantling of liberal democracy in Hungary, while Angela Merkel’s staying power is mainly attributed to her moral steadfastness and statecraft. But since those qualities are hard to find in Rutte (his handling of the MH17 airplane crash in Ukraine being the rare exception), it remains anyone’s guess as to what ‘the meaning of Mark Rutte’ actually is, either because it is impossible to attribute a single meaning to Rutte or perhaps because nothing more than a medium-length essay (such as the present one) is required to sketch the man and his ‘ideas’.

Mark Rutte as chameleon

At first glance, Mark Rutte’s political legacy appears to be far from unambiguous. In her book Mark: Portret van een premier (Mark: Portrait of a Prime Minister), Sheila Sitalsing illustrates how Rutte often changed positions both in the run-up to and during his premiership.3 In the nineties, he directly opposed his party’s right-wing leader, Frits Bolkestein, and advocated for a cabinet with the PvdA (Partij van de Arbeid, or Labour Party). In the noughties, he tried to create a furore with Groen Rechts (Green Right). That same decade, he narrowly managed to secure victory against the more radical right wing Rita Verdonk in the leadership elections of the VVD (Volkspartij voor Vrijheiden Democratie, or People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) and then expelled her from the party.

Yet when he took office as prime minister in 2010, he did so with a cabinet ‘where right-wing Holland would be licking its fingers’ (a phrase mentioned often in Dutch books and media). He soon came to be known as the ‘laugh-it-off prime minister,’ but one should not forget that at his first appearance in the Chamber he was widely praised for the fact that, unlike his predecessor Jan Peter Balkenende, he spoke in plain language and gave clear answers.

That fame would quickly fade in his second term. ‘Now you are doing it again,’ Labour leader Diederik Samsom remarked during the 2012 election campaign, when he referred to Rutte’s tendency to distort facts about other politicians’ programmes in order to make his own political agenda sound better. The two joined forces a few weeks later under the second Rutte cabinet, which will mainly be remembered as the cabinet of broken promises: every working Dutch person would receive eight hundred euros; no new aid package would go to Greece; and the mortgage interest deduction had the rock-solid support of the VVD.

One by one, Rutte had to go back on these earlier ‘hard promises’. Nevertheless, the pursued course came only partly at the expense of his VVD, and it was mainly the PvdA that had to pay the electoral bill for the forced but, above all, unhappy marriage. (It was a marriage that was mainly agreed upon to pull the Netherlands out of the economic crisis, but it would eventually last longer than many expected, and perhaps longer than was necessary.) Rutte II became not only the first cabinet since Kok I (1994-1998) to complete its entire term of office but also the longest-serving cabinet in Dutch history.

The 2017 elections marked Rutte with a number of new labels. Jesse Klaver, leader of GroenLinks (Green Left), called him ‘smooth as an eel’. Rutte was able to ‘avoid questions’ like no other, ‘ignore the arguments of others and merely tell his own story’. When, after the elections, Rutte negotiated a new cabinet with CDA (Christen-Democratisch Appèl, or Christian Democratic Appeal) and D66 (Democrats 66) in combination with GroenLinks (GreenLeft) and then the Christen Unie (Christian Union), the leader of the PvdD (Party for the Animals) speculated that Rutte might turn out to be a ‘green chameleon’.

As chairman of the youth organisation of his party (JOVD), the PvdD leader said, ‘he was already arguing for environmental taxes. In his twenties he considered that more important than reducing the national debt.’ But despite what had been described as the largest ever investment in sustainability, the third cabinet’s sustainability plans, which had been difficult to establish, would be insufficient for the left-wing opposition. The plans also failed to keep Dutch commitments to international climate agreements, especially when their ambitions were gradually scaled back due to farmers’ protests.

This article first appeared in the Dutch Review of Books, reviewed by Eurozine.

Mark Rutte as crisis manager

Initially, Rutte III would mainly be characterized by Rutte’s amnesia. He claimed to have ‘no active memory’ of intelligence about the more than seventy civilian deaths in Iraq stemming from a Dutch bomb attack in 2015, nor could he remember internal memos about the planned abolition of the dividend tax. Although he emerged from these debates unscathed, the abolition of the dividend tax, which would mean a revenue loss (mainly for foreign shareholders of multinational corporations) of 1.9 billion euro, would ultimately fail.

Earlier that year, the cabinet itself had overturned the possibility of a corrective referendum on parliamentary laws. Both measures could be added to the growing list of plans that should have been realized under Rutte’s tenure, but ultimately did not succeed (or did but were eventually reversed), including a fine for long-term students, the criminalization of undocumented migrants and a speed limit increase to 130 km/h.

Still, more than anything else, Rutte III will probably be remembered for its response to the corona crisis. Six months prior to the start of the pandemic, Rutte declared the so-called ‘nitrogen crisis’ and its accompanying farmers’ protests to be the ‘biggest crisis’ of his career as prime minister.

Indebted to his liberal ideology, but also to some degree to the1960s legacy of Dutch free thinking, he carefully stayed away from the solutions that many southern European countries pursued and wasn’t tempted into warlike rhetoric used by Emmanuel Macron nor the strongman language of American or British heads of state. Rather, he chose to appeal to people’s own sense of responsibility and won over a considerable portion of the population as a result, despite limited measures, or what he referred to as an ‘intelligent lockdown’ (e.g., shops remained open and there was no curfew). Excess mortality was lower in the Netherlands than in Belgium or Great Britain, where policies were far stricter or more relaxed.

In her book Mark Rutte, Petra de Koning also illustrates how Rutte is at his best when politics is reduced to crisis management and the solving of a specific problem.4 Though his public address to the nation may not have had the élan of Joop den Uyl’s during the Oil Crisis almost 50 years earlier, Rutte’s lack of allure as a statesman makes him all the more approachable.

At the start of his career, it seemed a bit of an act, as if he had learned to speak mainly from PR coaches and debate experts and to act in an easygoing, if somewhat feigned, way. As Sitalsing lucidly remarks, Rutte’s speeches include logos (reasoning) and ethos (trustworthiness), but completely lack pathos, or the appeal to the emotions and imagination.

Nowadays he seems to have developed a considerable mastery of this jovial attitude and knows how to effortlessly combine it with a more natural, assumed professionalism. In any case, he has managed to hit just the right note during the corona crisis, making himself immensely popular after joking ‘we can all poop for ten years’ (following toilet paper sales and hoarding). At all levels of society, Rutte’s popularity rose to unprecedented heights thanks to his approach to the crisis. Had the pandemic lasted only one wave, then the opposition would hardly have dared to take up arms against his policies.

Mark Rutte as mediator

The question remains whether a certain continuity can be observed in roughly ten years of successive Rutte cabinets. Should we regard Rutte and his cabinets as a break with the past, or did he continue on the same path as his predecessors? Books on Rutte hardly ever dare to answer these questions.

De Koning begins with the word ‘adapt’ as the credo of Rutte’s leadership, which is not followed by a chronological consideration of his whirlwind ascent but rather a detailed description of how various political manoeuvres intersect with his personal life. In discussing the many agreements that Rutte made during his time in office, de Koning demonstrates a keen understanding of the political and personal interventions that were necessary.

His first cabinet started with the controversial parliamentary support agreement with the radical right-wing PVV (Party For Freedom) of Geert Wilders and concluded with the so-called ‘spring agreement’ because Wilders withdrew support for Rutte’s cabinet. Those agreements were followed by agreements for energy and housing in 2013, the tax agreement in 2015, and, more recently, the pension agreement and the climate agreement.

De Koning does not discuss what these agreements yielded, but occasionally presents facts and anecdotes that provide insight into the consequences of Rutte’s politics: a Moroccan-Dutch former pupil who was able to move up in society in spite of, rather than thanks to, Rutte; self-employed cultural workers that suffered from huge budget cuts; and disabled former workshop workers who now sit at home following closures by the second Rutte cabinet.

In addition, she discusses the European Union, where Rutte is always obstructive and paternalist (especially with regard to Southern-European countries). Meanwhile the Netherlands is nowhere near meeting its European targets on issues such as sustainable energy. In this respect, the Netherlands is now firmly in last place, with less than ten per cent of its energy coming from renewable sources.

Interestingly, De Koning provides examples of when Rutte’s reliance on adapting fails to produce significant results. CDA senator Hannie van Leeuwen was uncompromising when Rutte was State Secretary of Social Affairs, and PvdA senator Adri Duivesteijn refused to cooperate during Rutte II’s healthcare reform. Both got their way but are exceptions, as Rutte rarely faces any real opposition.

Photo via Minister-president Rutte from Flickr

Mark Rutte as Teflon

Indeed, criticism of his policies rarely has repercussions for Rutte himself. What these books mainly focus on is how he knows better than anyone how to avoid difficult questions or issues, how to depoliticize his own policies and, above all, how to stay out of harm’s way. Whereas VVD ministers had to leave his cabinets by the handful, Rutte never suffered any real consequences, even though he consistently refused to publicly abandon his departing colleagues. As a result, Rutte, at least in the first half of his premiership, was often criticized for having no vision.

In Mark Rutte:Alleen voor de politiek (Mark Rutte: Only for Politics), Martijn van der Kooij and Dirk van Harten come closest to accurately describing Rutte’s political ideology or vision. 5 However, they rely mainly on the testimonials of colleagues within the VVD, who may also project their own views onto him. Since Rutte has never actually written or described his ‘vision’ or ideology, he cannot be held accountable for one.6 The most significant thing that he has said has been that he ‘wants to arrange a few things, really change them,’ but he never has actually said what those things are.

Yet, as Van Harten and Van der Kooij point out, Rutte wrote the new ‘statement of principles’ of the VVD in 2008 and even used the word ‘neoliberal’ (‘the idea of a small government, more market forces and public-private collaborations’ as they define it) to characterize the document. But he has hardly developed the idea.7 In his 2013 H.J. Schoo lecture, he called the vision an ‘elephant that obstructs the view’ (to the delight of commentators and satirists). ‘I don’t believe in comprehensive blueprints that are to be used to solve social problems in one fell swoop,’ Rutte continued, ‘as a liberal I always get a little suspicious of that sort of thing.’ Such statements align Rutte with the many historical characterizations of Dutch governing elites as being largely uninterested in rationalist ideologies or political abstractions.8

Although Van Harten and Van der Kooij make their main comparison with Willem Drees, I prefer to argue that Rutte belongs on the same list as Jan Peter Balkenende, Wim Kok and Ruud Lubbers, who all preceded him in the pursuit of a murky politics of compromise, backrooms and depoliticization. While Balkenende came up with the ‘Dutch East India Company mentality’ at the end of his premiership, Rutte, after his ‘vision as an elephant’ lecture, did not get much further than presenting the Netherlands as a ‘vase upheld by all of us together’. Although Rutte may refer to himself as the first liberal prime minister in a little under a century, when it comes to having a precise vision he hardly differs from his predecessors.

Still, if something can be labelled ‘Ruttian’ it is precisely these kinds of rhetorical tricks in which criticism is not so much fought but cultivated and presented as a strength. As the above example shows, the absence of a vision is not a defect but something useful since it does not hinder him. Following criticism of the plan to abolish the dividend tax, which peaked in the summer of 2018, he agreed with the opposition’s characterization and admitted that it was a ‘bizarre’ measure ‘because nobody gives 1.9 billion to foreign shareholders just for kicks.’

If, as in France and Belgium, a yellow vest movement threatens to emerge in the Netherlands, Rutte does not seem ill-disposed towards it. Rather, he dons a vest himself, giving the impression that he is on the side of the critics with regard to the policy being pursued (which is, in fact, his own).

Mark Rutte as populist

But sometimes Rutte goes a step further and engages in provocative behaviour. In the run-up to elections especially, he likes to take a step to the right: he was rather harsh in his assessment of harassment vloggers; he said that he would ‘prefer to personally beat up’ all the people who bothered first responders on New Year’s Eve; and he told some young people who chased away a national news media camera crew to ‘piss off’.

In response to the recent riots that broke out after a government-instituted curfew, he emphasized that the rioters were ‘criminals’ and that he refused to ‘look for sociological explanations.’ In summary, his message reiterated his 2017 campaign slogan: ‘act normal or go away’.

In political science, this kind of muscle-flexing language is called ‘parroting the pariah’ and cannot be viewed in isolation from the rise of the radical right. It is also regarded as an important driving force behind the general shift to the right that we have seen in recent decades and has gained momentum over the past ten years. In response to the rise of radical parties, establishment parties first label these ‘challengers’ as pariahs before adopting much of their rhetoric and positions.

The classic example is the election of Nicolas Sarkozy in 2007 in which he replaced the decades-long strategy by the left and right of excluding Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Front National. In its place was a strategy of imitation, so that the majority of Le Pen’s voters ended up switching over to him, thereby blurring the line concerning what was seen as acceptable in French politics. Many commentators in France saw Le Pen’s electoral loss as a victory over his ideas. Rutte has also excluded the PVV (Partij voor de Vrijheid, or Party for Freedom) as a potential coalition partner, declaring them a pariah because of the calls for fewer Moroccans by PVV-leader Geert Wilders.

Meanwhile, Rutte’s VVD seems to have strayed further and further away from his original and more tolerant course. In the areas of refugee policy and migration, the VVD position is now much more in the tradition of Bolkestein and Rita Verdonk, Rutte’s first major opponent.

More than anything, Rutte instrumentalizes the radical right for his own political ends. For example, he sometimes actively seeks confrontation with challengers or ‘the wrong kind of populism,’ as was the case in the 2017 elections with the PVV, the 2019 European election with the FvD (Forum voor Democratie, or Forum for Democracy) and, most recently, with the partly extreme right anti-curfew rioters.

In this way, he tries to create a kind of conflict, which further sidelines left-wing parties. The question remains as to what extent he really sees those ‘wrong sort of populists’ as a problem. For example, Rutte has no problem with promoting a photo of himself from Davos in which he stands shoulder to shoulder with the extreme right-wing Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro. In a similar vein, Donald Trump had to be viewed as ‘an opportunity,’ while the actual problem was with the ‘white wine-sipping Amsterdam elite’ that was so often upset by Trump.

It is tempting at first to characterize ten years of Rutte as ten years of shifting to the right and to regard him, just like Nicolas Sarkozy, as the ‘mainstreamer’ of the radical right. But this characterization is not entirely accurate. In a way, Rutte’s strategy of shifting to the right to limit the growth of the more radical is a page right out of Nicolas Sarkozy’s playbook (although the latter took the conflict of ideas a lot more seriously).

In his The Meaning of Sarkozy, Badiou, for example, portrays the French president as a sort of ‘rat man,’ one who had launched a head-on offensive on the ’68ers and wanted to undo everything they stood for. Communism had already disappeared, but it was also important for Nicolas Sarkozy to wipe out the idea for good.

In the ranks of the PvdA, Van der Kooij and Van Harten write, a campaign film also tried to portray Rutte as a ‘rat’. He was able to dismiss it, however, by calling it ‘sad’ that the PvdA would stoop to such a thing and this image smoothly slipped off of him as well. Such attempts to dehumanize a government leader may resonate when it comes to Sarkozy but not with Rutte. When he brings up national identity, he just pays lip service to the nationalist flank of his party.

Photo by Arnold Bartels, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Prime minister of all Dutch people?

Much more than an initiator or a facilitator of the swing to the right, Rutte represents the perfection of the almost anti-political attitude of the Dutch establishment. He should not be considered a driving force but rather as a state manager who simply added another decade to a shift that had been going on for thirty years.

Rutte does not distinguish himself qualitatively but quantitatively from his predecessors: he is more fickle, more pragmatic, more elusive, while at the same time less important or simply more meaningless. In searching for the meaning of Rutte, we can primarily regard his behaviour as opportunistic, which is in keeping with a long tradition within the Dutch political establishment of moving to the left or right whenever it is politically expedient to do so.

A case in point is Rutte’s changing position in the Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) debate, involving the blackfacing the Black Petes, who help Sinterklaas (the Dutch Santa). The debate lasted a decade and therefore defines his time in office. Protests, which had already begun in 2009, resulted in a United Nations report in 2014 that concluded Zwarte Piet was indeed a racist caricature and the tradition needed to be changed.

Rutte neither acted nor commented on the report, defending himself by saying, ‘then it would seem I have a policy opinion on this’. In 2015, he observed that ‘it really makes a difference if your name is Mohammed or Jan when you apply for something,’ before continuing, ‘I have thought about it and came to the conclusion that I cannot solve it. The paradox is that the solution lies with Mohammed. […] Newcomers have always had to adapt and have always faced prejudice and discrimination. You have to fight your way in.’

Even when in November 2019 the group ‘Kick Out Zwarte Piet’ was violently attacked by right-wing extremists during a private meeting, they had no reason to expect an invitation from the prime minister like the handful of Yellow Vests or the Youth for Climate movement (who, however small, were immediately invited).

As one of Rutte’s guiding principles, laissez-faire extends far beyond the free market. Only when thousands of people in various cities took to the streets to protest racism and police violence in spite of the ongoing pandemic was Rutte willing to emphasize that racism also occurs in the Netherlands. He even said that he had changed his stance on Zwarte Piet. Change required targeted protests and mass mobilization, but the prime minister merely moved in a different direction, thereby avoiding resistance and direct confrontation.

In that sense, Rutte (a self-proclaimed Anglophile) is much closer to David Cameron than to Nicolas Sarkozy. David Cameron also insisted on being ‘progressive’ on a number of fronts, although, according to Richard Seymour, this was mainly due to the creeping conservatism and the authoritarian turn of New Labour. In fact, David Cameron was, in Seymour’s words, mostly a ‘non-entity’, someone who did nothing more than channel the prevailing zeitgeist.

Cameronism, in this sense, was little different from another chapter in the restorationist project that had been set in motion at the end of the turbulent 1970s. As Seymour writes, it was ‘an attempt to restore the social power and profitability of capital […] by breaking the power of organized labour. This was always going to involve pacifying a restive population, narrowing the political field and marginalising the working class majority’. There is hardly a better way to describe Mark Rutte’s politics.

David Cameron’s career as prime minister came to an end in 2016 with the result of the Brexit referendum. Nicolas Sarkozy’s fate had already been sealed in 2012. In France, François Hollande was only able to hold on for another five years after which the entire party system imploded, with Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron emerging from the ballot box as the most important political players.

Meanwhile, in the UK, after David Cameron’s resignation, Theresa May stepped up in order to restore the peace, but a period of strong polarization and politicization soon followed, stirred initially by leftist Jeremy Corbyn and then intensified by Boris Johnson on the right.

Photo by CDU Sachsen, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

With the exception of Angela Merkel, only Rutte managed to survive the decade politically (without dismantling democracy). And where Angela Merkel has indicated that she will end her political career in 2021, Rutte stated in 2019 that he would prefer to remain prime minister for the rest of his life, an ambition that does not seem to be in jeopardy. As long as he leads everyone in the polls, no one dares to turn against him, which eventually spoils their chances to collaborate after the elections.

All parties really do dance to the tune of Mark Rutte. Even the SP (Socialistiche Partij, or Socialist Party) has for the first time not ruled out the VVD as a potential coalition partner after the elections. Thus, it is telling that the recent fall of Rutte’s third cabinet is not the result of strong opposition but of a government failure (i.e., the aforementioned benefits scandal).

Rutte has not suffered in the polls. And although he has seized every opportunity to shift the focus to his law-and-order approach to the rioters following the curfew decree, the benefits affair will affect his legacy. Within the public’s mind, the benefits affair, which is the result of socio-economic, cultural and ethnic profiling by the tax authorities, has increasingly come to be seen as the result of a policy-based translation of the VVD rhetoric surrounding ‘the hard-working Dutchman’ and the suspicion of those who seemingly did not fit this definition.

Over time, the institutional distrust that had been established turned against the same hard-working Dutch people, but all the signals were ignored. And, under the cover of Rutte’s policy of opaque transparency (recently termed the ‘Rutte doctrine’), nobody saw the need to intervene. Yet, despite the fact that the lives of many innocent people were ruined by the benefits affair, Rutte refuses to step away from politics. Therefore, his legacy will perhaps not be seen as ten years of shifting to the right but rather as ten years in which the principles of good governance decayed.

Or were made rotten by Rutte.

R. Seymour, The Meaning of David Cameron, Winchester: Zero Books, 2010.

A. Badiou, The Meaning of Sarkozy, trans. D. Fernbach, London: Verso, 2008.

SheilaSitalsing, Mark: Portret van een premier(Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2016).

P. de Koning, Mark Rutte, Leiden: Uitgeverij Brooklyn, 2020.

M. der Kooij and D. van Harten, Mark Rutte: Alleen voor de politiek, Arnhem: Terra, 2010.

See also: J. de Vries, De Gelukkigste man van Nederland, Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2021.

To be fair, a well-known and rare exception to this was his reply to a question on TV-programme NPO College Tour. When asked to state his ‘sweetest wish for the Netherlands,’ he replied: ‘That people who want to start a business can do so within a day, without bureaucracy. And that the government does not bother companies with checks all the time.’

See also: M. Oudenampsen, The Rise of the Dutch New Right: An Intellectual History of the Rightward Shift in Dutch Politics, London: Routledge, 2020.

Published 15 March 2021

Original in Dutch

Translated by

Tyler Langendorfer

First published by Dutch Review of Books 1/2021 (Dutch version), Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Dutch Review of Books © Jouke Huijzer / Dutch Review of Books / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The imprisoned Belarusian opposition politician Maria Kalesnikava has been in a critical condition since the end of November. In October she was awarded an honorary professorship at the University of Salzburg. The philosopher Olga Shparaga, a fellow member of the exiled Coordination Council, pays tribute to a feminist legend.