Measures such as ‘ethical AI’ and ‘good data’ will not bring about social justice, end racial capitalism or forestall climate disaster. How to channel discontent and counter-hegemony into an actual transfer of power in the late platform age?

Embezzlement, bribery and false testimony: Austria’s no-longer chancellor Sebastian Kurz is accused of serious crimes. He appears confident that legal charges will not stick; but the political judgement will be made by the Austrian public.

Austria has had its fair share of scandals, but this was a first: on 9 October, following police searches of the federal chancellery, the finance ministry and the headquarters of the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), chancellor Sebastian Kurz announced his resignation. But it was not and is not a proper resignation, rather a temporary withdrawal – from the chancellery to parliament. As leader of the ÖVP parliamentary faction and as party chairman, he will continue to pull the strings. As the party put it, Kurz was merely ‘stepping to one side’.

This step to one side is intended to ensure that the massive accusations against him miss their mark. With very few exceptions, the ÖVP stands behind him in blind obedience. If, as Kurz hopes, the charges fail to stick, he will stage a triumphal comeback at the next election. That wasn’t in his resignation speech, but it is part of the plan.

A hint of regret also belongs to that plan. But it is a hint that reeks of hypocrisy, since what Kurz regrets are not the many offences carefully detailed by the investigators, based on seized emails and text messages. These offences are why Kurz and his team are being charged with corruption and abuse of office. No, what Kurz regrets is the tone of the messages, the foul language and the insults: particularly the frequent use of the word ‘arse’ in connection with his political predecessor. Kurz tried to dismiss his indecency by claiming they were ‘messages that I would definitely not formulate in the same way again, but I’m only human and have emotions and faults’. The aim was apparently to distract from the fact that he had talked of ‘inciting’ a federal state to rebel against the ÖVP government.

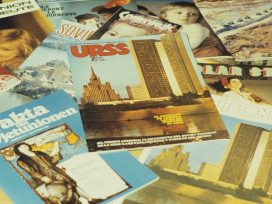

Newsagent in Vienna, 2017. The election poster reads: ‘Now. Or never!’ Photo by Anton-kurt, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Under the circumstances, it is worth recalling the election campaign that brought Kurz into the Austrian chancellery. The posters showed a brylcreemed young man smiling and promising change: ‘Kurz 2017’ read the slogan: ‘A new style. It’s time.’ Sebastian Kurz was then 31 years old; he had begun training as a lawyer but, as his biographers write, had preferred politics to studying. For the previous four years, he had been a highly networked, hyperactive and power-conscious foreign minister.

With this new ‘style’, Kurz managed to oust Reinhold Mitterlehner as ÖVP chairman. But the newly appointed leader wasn’t much interested in the old party: he put the ÖVP in brackets and campaigned under the name ‘List Sebastian Kurz – the New People’s Party (ÖVP)’. List Sebastian Kurz emerged as the clear winner, improving on the ÖVP’s 2013 result by 7.5%. Kurz became Austrian chancellor and formed a government with the far-right FPÖ. What happened next is well known.

‘A new style. It’s time.’ This new style was and is deeply off-putting. The public prosecutor for financial crime and corruption suspects him of serious offences. Kurz’s team and him personally are under investigation for embezzlement at the expense of the Republic of Austria, of bribery and of false testimony. What emerges from the facts listed in the public prosecutor’s 104-page report is not just shocking but also deeply disturbing.

The report provides a glimpse into a bottomless pit of contempt for democracy. The cache of several hundred thousand chat messages secured by the public prosecutor clearly reveals that Kurz and his team paid for manipulated opinion polls. These manipulated opinion polls were then turned into a series of articles favourable to Kurz. The fake reports were published in the tabloid cosmos of Wolfgang Fellner, owner of the television station oe24 and the mass-circulation newspaper Österreich. All of this was paid for out of the budget of the finance ministry, in other words with public money. The public prosecutor is referring to the corrupt involvement of political actors (i.e., Kurz and his team) with a media publisher.

If that is true – and the facts speak a clear language – then it is a treble disaster: first for democracy, second for the rule of law and, third, for press freedom.

The evidence of the public prosecutor suggests that a publisher allowed himself to become the hireling of Kurz and his team. Doctored and falsified content mislead the public – paid for by the taxpayer. In Austrian law, embezzlement is punishable by up to ten years. In earlier days, such crimes brought the revocation of civil liberties, including the right to stand for public office.

In addition to the new allegations comes an older one: on the 6 May 2021, the public prosecutor informed Kurz that he was under investigation in connection with the Ibiza affair. As revealed by the Süddetutsche Zeitung and Der Spiegel in May 2019, Heinz-Christian Strache, the FPÖ deputy chancellor in the Kurz government, and Johann Gudenus, head of the FPÖ parliamentary faction, had two years earlier met with the alleged niece of a Russian oligarch in a villa on Ibiza. During a lengthy conversation, they had bragged about their willingness to bypass laws on party financing – and about taking control of independent media.

Kurz was accused by the prosecutor of providing a false testimony at the parliamentary commission set up to investigate the Ibiza affair (albeit on a matter not directly related to the affair itself). If the charges are true, it now turns out that Kurz had practiced in 2017 what Strache and Gudenus had merely planned. In the interests of democracy, rule of law and freedom of the press, let’s hope that the charges are not true. However, the sheer weight of evidence gives little grounds for hope.

‘Team Kurz’: L-R Sebastian Kurz, Gernot Blümel, Elisabeth Köstinger. Photo by Bundesministerium für Finanzen, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The no-longer chancellor argues that he was not himself involved in the potentially criminal offences. In an interview with the Austrian public broadcaster ORF, he claimed he had not known which colleague had been doing what. He pretended not to have anything to do with the matter, as if it would anyway evaporate at some point.

But it won’t – for legal reasons if nothing else. Austrian law recognizes the principle of incitement to an offence. Not just the immediate offender can commit a crime ‘but also those who order another to carry it out or who otherwise contribute to it being carried out’. This could be what does for Kurz. His attempt to play the matter down is understandable, but, as lawyers say, it is a Protestatio facto contraria. In other words, it contradicts the facts.

On the very evening of his resignation, Kurz self-pityingly lamented that he would be grateful if the principle of innocent until proven guilty ‘could actually be applied to everyone’. These were crocodile tears. Whether, how, and how strictly his actions are investigated remains to be clarified; there is a legal process for this. But a political judgement of the situation can and must be made now, not in months to come. After all, the facts are there for all to see. Kurz and his team are not going to make them go away by claiming that the public prosecutor has been infiltrated by ‘leftwing cells’.

Within Team Kurz there was discussion about how to harm the public prosecutor via the media. A now suspended departmental head in the ministry of justice is accused of passing information about impending house searches to the people involved. A central figure in Team Kurz is suspected on the basis of this tip-off to have tried to delete all the data on his telephone before it could be confiscated by the investigator. This telephone is central to the investigation.

The affair has led to the political conclusion that the Kurz chancellorship has been poisonous for democracy. So far, however, Kurz has been able to brush off the accusations like water off a duck’s back. Just in case that doesn’t work, he simply steps to one side.

When Kurz became ÖVP chairman, he made sure that he received extensive prerogatives. As no-longer chancellor, he continues to sit on a throne of statutes. As chairman, he has far-reaching rights of intervention and veto, and he has the say in the appointment of ÖVP candidates for parliament and other important posts. In other words, even after handing over his chancellery to Alexander Schallenberg, the former diplomat and foreign minister Kurz continues to decide the political course of the ÖVP.

If Karl Kraus’s famous play Die Unüberwindlichen (‘The undefeatable’) had been set in the present, the characters would be members of ‘Team Kurz’. Written in 1927, the play is about journalistic and political corruption. Kraus detested the indifference with which Austrians reacted to nepotism, favouritism, bribery and corruption in all its forms. ‘When the constitution is violated in Austria,’ Kraus wrote in the first issue of Der Fackel in 1899, ‘the population yawns’. In the intervening 120 years, it seems something has changed after all.

As Kurz put it so poignantly in his farewell speech: ‘My country is more important than my person … What it needs now is stability. To solve the impasse, I am making way, in order to prevent chaos and to guarantee stability.’ This was to openly ridicule the Austrian public. The stability that Kurz stands for is the stability of contempt for democracy.

Karl Kraus is often credited with a quote that would be appropriate to this situation: ‘Austria is the only country that grows more stupid with experience.’ But it is a false quote. At least, it is not from Kraus. More importantly: let’s hope it isn’t true.

Published 28 October 2021

Original in German

Translated by

Simon Garnett

First published by Blätter 11/2021

© Blätter

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Measures such as ‘ethical AI’ and ‘good data’ will not bring about social justice, end racial capitalism or forestall climate disaster. How to channel discontent and counter-hegemony into an actual transfer of power in the late platform age?

The effectiveness of Kremlin propaganda is based on a tangled bundle of lies and half-truths. Reality, however, cannot be distorted forever. As Europe needs to bring vision back to politics, can Russians finally emerge from their echo chamber?