In the Danish online journal: Ignác Semmelweis, hand soap and the hygiene revolution; history of vaccination in Denmark; and Madagascan bathing rituals and the language of anthropology.

In Danish online journal Baggrund, a new partner in the Eurozine network, Tanne Schlosser Søndertoft provides a history of hand soap — an object that has saved millions of lives.

In Danish online journal Baggrund, a new partner in the Eurozine network, Tanne Schlosser Søndertoft provides a history of hand soap — an object that has saved millions of lives.

Soap had been used for centuries for cleaning clothes and kitchen utensils before its benefits to public health were discovered. Only in the mid-nineteenth century did Ignác Semmelweis introduce it into the maternity ward of Vienna’s general hospital. Washing hands proved to be not only a hygienic revolution, but also a cultural one, ‘accelerating work on sewers in cities, the installation of water taps, flush toilets and in-home baths’.

History of vaccination

Smallpox outbreaks recurred every 4 to 7 years in eighteenth-century Copenhagen, primarily affecting children, writes Martin Kristensen. English medicine student Edward Jenner was the first to dare to experiment with vaccination, deliberately infecting a child with cowpox. Not all authorities approved: ‘Religious anti-vaccination groups protested against such pagan conduct as using a cattle disease to cure a human being.’ However, as early as 1810, Copenhagen made the smallpox vaccine obligatory and the illness was never seen again.

Anthropology of bathing

Anders Norge Lauridsen tracks bathing rituals in Madagascar and the different ways in which they serve to ‘purify’. Indonesian, East African and Islamic influences, as well as those of French colonialism, show up in Madagascan bathing rituals, writes Lauridsen. Accounting for these intercultural connections requires that the local vocabulary for concepts such as ‘purity’ be taken into account.

More articles from Baggrund in Eurozine; Baggrund’s website

This article is part of the 10/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter, to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing

Published 8 June 2020

Original in English

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Vast regimes of cultural practice serve to transcend one’s physical existence and ensure living on symbolically through language, culture, and nationhood. While some fear the eradication of minority languages, others dread losing their group’s hegemony. But all run into trouble when faced with the apocalyptic rhetoric of climate activists.

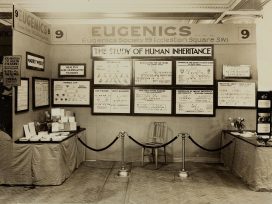

Many of the early twentieth-century champions of eugenics were social democrats and feminists. All shared a belief that science and technocracy could re-engineer society for the better. Attempts to institutionalize eugenics coincided with the emergence of welfare states and infrastructure to monitor the ‘feebleminded’.