In ‘Kultūros barai’: why the pandemic has brought out the worst in Lithuania’s politicians; whether there is such a thing as an individual common good; and how the Jewish history of Žagarė reaches into the present.

‘In Lithuania, dissatisfaction with the government and its decisions in various areas of public life is not only persisting but growing,’ writes Almantas Samalavičius in Kultūros barai. ‘Spontaneous outbursts of violence, or violence that has been secretly and cleverly instigated by someone else, naturally discredit the rally organizers, but they should not be lumped together. The activism of those who find the attitude of the Seimas [parliament] and the government towards the family unacceptable, and who resent social policy and/or the management of the pandemic, should not, it seems to me, be either surprising or intimidating.’ The government’s intransigence for refusing to enter into dialogue with the protesters shows a lack of professionalism, according to Samalavičius.

He also lambasts Daiva Razmuvienė, an epidemiologist at the National Public Health Centre, for trying to scare the public in March 2021 by writing: ‘We have to understand there is a war going on, and a biological war at that, so, in my opinion egoistic demands should be forgotten.’ Samalavičius concludes with the words of the celebrated Lithuanian writer Ričardas Gavelis (1950–2002), written in the immediate post-Communist years: ‘Our time is marked by the unbounded domination of dilettantes. This is our tragedy; this is our terrible fate.’

Who defines the common good?

Philosopher Nida Vasiliauskaitė’s appeal for resistance to compulsory vaccination prompts Laisvūnas Šopauskas to delve into theories of the common good. Vasiliauskaitė’s has argued that political decisions cannot be based on references to the common good since a) the common good does not exist and b) nobody knows what it is. The fiction of the common good is dangerous, she says, because it leads to dictatorship and totalitarianism; the most important freedom is the ability to choose one’s own understanding of the common good and to live in accordance with that understanding.

These ideas sound compelling, Šopauskas writes, but from a philosophical point of view contain ‘a tangle of errors’. ‘The individuals that Nida Vasiliauskaitė glorifies will certainly not be able to defend their rights and freedoms, because they are defending only their own bodies and businesses, without understanding the need to defend the nation and the state.’

Jewish history

Dalija Epštinaitė presents the history of the Jewish population before the Holocaust in the town of Žagarė (Zhager in Yiddish) in the north of Lithuania close to the border with Latvia. Žagarė is exceptional in having produced so many famous Jews, not to speak of the Sages of Zhager – teachers of the Talmud, preachers, yeshiva leaders and authors of treatises. Žagarė’s proximity to the Courland (Kurzeme) region in western Latvia, through which the Jewish Enlightenment came, may explain this. Today, the descendants of emigrants visit their ancestral homeland in order to breathe the air of the Centre of Jewish Wisdom, and to sample the local cherries – held to be the best in Lithuania.

This article is part of the 16/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 13 October 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

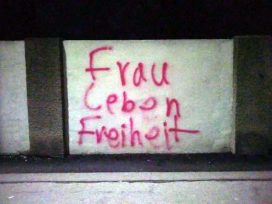

Allen Risiken zum Trotz

der Kampf für die Demokratie

The imprisoned Belarusian opposition politician Maria Kalesnikava has been in a critical condition since the end of November. In October she was awarded an honorary professorship at the University of Salzburg. The philosopher Olga Shparaga, a fellow member of the exiled Coordination Council, pays tribute to a feminist legend.