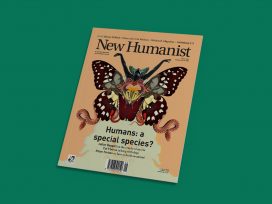

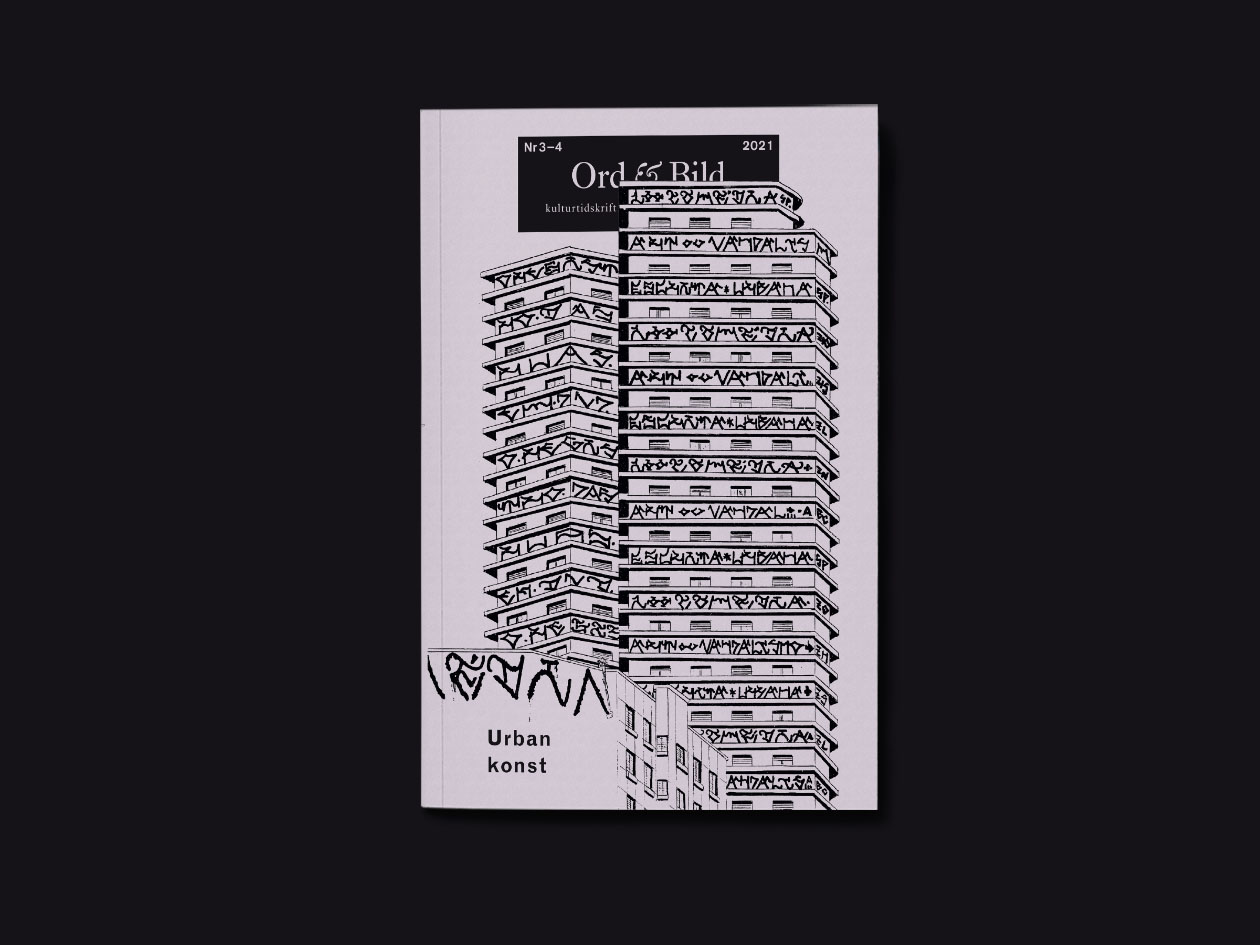

‘Ord&Bild’ features urban art: with articles on the aesthetic boundaries pushed by graffiti pioneer Zevs; the sanitization of the underground in Swedish cities; and transgender cultural organizing in São Paulo.

An issue of Ord&Bild on urban art, guest edited by Daniel Terres and Patrik Haggren, opens up the questions: Which urbanity? What art? And how does urban art relate to institutions and contemporary art?

Is graffiti art or vandalism? Both, argues Toke Lykkeberg, in his article on the pioneering French graffiti artist Zevs. ‘If we must answer the question whether graffiti – and everything else Zevs has done since he started writing – is art, we have to figure out what we understand by art.’ A comparison with the work of public artist and sculptor Daniel Buren helps:

‘Whereas Buren at work has the feeling of breaking a set of rules, namely those of art, Zevs has a feeling of submitting to a set of rules, those of the city or whatever system he integrates. This is why Buren covers up the city, putting striped posters on top of other posters, whereas Zevs enhances certain characteristics of the city by rendering visible its shadows, its imagery, or its pollution. If Buren can be understood as part of an avant-garde, which is ahead of something such as a museum, Zevs is arrière-garde, since he always intervenes on something that others have left behind.’

Sanitizing the underground

Patrik Haggren and Daniel Terres contribute with a text on how public attitudes to urban art have shifted from zero tolerance to a tolerance with reservations. They provide examples of how city branding utilizes the aesthetics of street art while at the same time regulating other expressions – and how these strategies relate to the segregated city:

‘Despite the creed of cultural policy to promote artistic freedom, it previously hindered imagery identified as graffiti and street art from taking place on public initiative in cities such as Stockholm, Helsingborg, Borås and Gothenburg. Today, the same cities market themselves with street art festivals, where art must stand for wellbeing and a safe urban environment through control of the content. Demonization has been transformed into “tolerance”. In a market-adapted and instrumentalizing discourse, aesthetics becomes either a tool to distance from or to bridge societal conflicts.’

Fredrik Svensk writes on aesthetics, liberation and how urban art has emerged in scientific literature. ‘A critical concept of urban art can be understood as an art of precarization, which in some sense corresponds to the gap that has arisen between the aesthetic culture’s promise of an educated bourgeois life and its economic conditions.’

Transgender cultural organizing

Brazil has the world’s highest rate of transphobic crimes in the world and life expectancy among the trans population is 35. The common destiny of most trans women in the country is some combination of homelessness and sex work. Although São Paulo has the highest number of trans persons affected by homelessness and poverty, social acceptance and visibility of HBTQIA+ persons is growing – not least as a result of the city being home to the largest Pride parade in the world.

Isabel Löfgren writes on collective strategies for care among artistically active transgender people in Brazil, focusing on the organization Casa Chama. The São Paulo NGO, Löfgren writes, ‘was created in 2018 to strengthen and protect the cultural production and lives of transvestigender artists as one of several grassroots mobilizations against the transphobic and anti-culture politics of Jair Bolsonaro’s extreme-right government. But soon after its beginning, the organization saw a much greater need to protect as many transvestigender lives as possible from trans necropolitics.’

In order to provide trans people with ‘a dignified life’, Casa Chama ‘mobilizes allied professionals to provide health and legal assistance, creates employment autonomy programs, works with damage reduction, strengthens trans governance together with trans politicians, fights administrative violence and campaigns for a constitutional basis for civil rights.’

This article is part of the 18/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 18 November 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

New ways to inhabit

Esprit 9/2021

‘Where do we live?’ In ‘Esprit’, texts on the end of France’s post-war social housing model, the diversification of home ownership, and learning from informal settlements. Also: what happened to Macron’s liberal revolution?

Mutualism, massive and the city to come

Jungle pirate radio in 1990s London

In the 1990s Britain was under Thatcherite continuity rule. But radio waves were appearing that carried fragments of the future: weekend broadcasts of a new kind of music – Jungle – were being illegally beamed across the city from improvised studios in empty flats, via aerials on tower block rooftops.