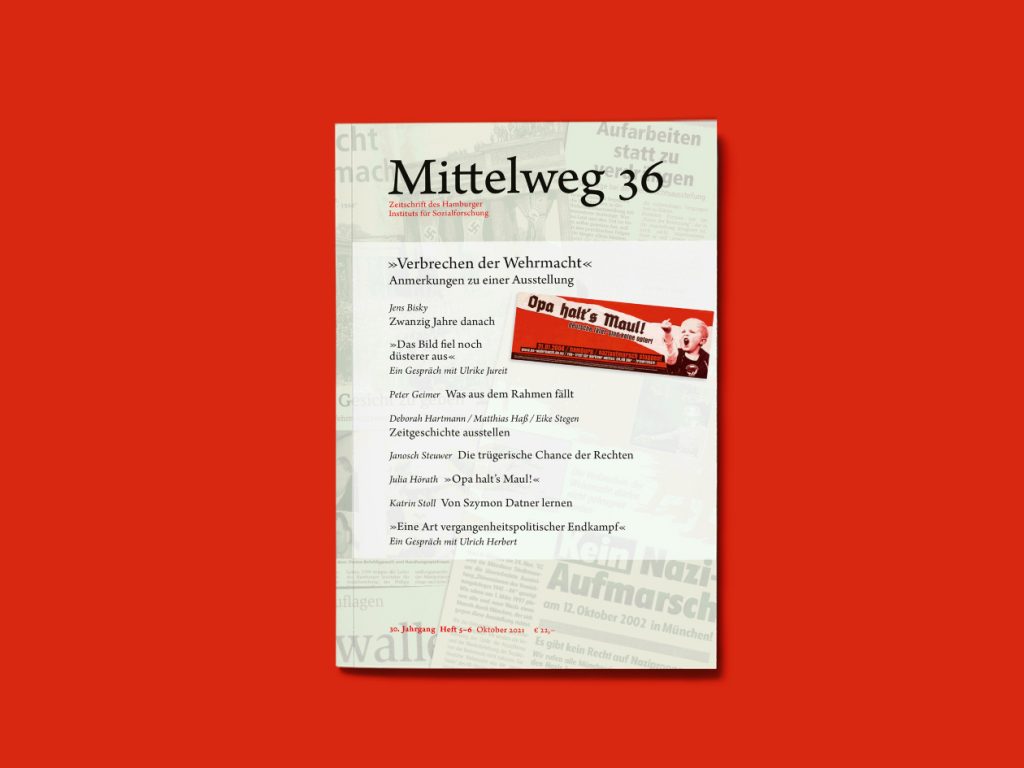

‘Mittelweg 36’ returns to the Wehrmacht exhibitions twenty years on: including the political and historiographic controversies surrounding the exhibitions and their impact on German public debate; also, how they realigned politics and mobilized both far-right and far-left.

Mittelweg 36 looks at the historical significance of the second Wehrmacht exhibition twenty years after its opening in Berlin in November 2001. Unlike the first exhibition, which opened in 1995 and sparked heavy controversy before being withdrawn by the organizers in 1999, the second, extended version largely took place in an atmosphere of consensus and objectivity.

The second exhibition’s inclusion of textual explanation was seen by some (including the first exhibition’s director) as a concession to the far-right critics of the first, which had presented photographs uncommented and had occasionally lacked historical precision. However, the general opinion was that, far from ‘relativizing’ the crimes of the Wehrmacht, the second exhibition represented major progress in public debate about the German past. That both exhibitions were themselves historical events is the premise of the current issue, writes editor Jens Bisky.

From politics to historiography

From 1999 onwards, says the historian Ulrike Jureit, the Wehrmacht debate ceased to be primarily a political one and became a historiographic one. This was the reason for the decision of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research to reconceptualize the exhibition in its entirety, rather than merely correct mistakes. However, the basic question remained: how could a photograph that did not show ordinary soldiers (as opposed to SS members) committing war crimes nevertheless prove the involvement of the Wehrmacht? ‘Because of the extremely tense debate, we needed material that was in this respect absolutely clear. And this clarity could to a great extent only be achieved through text.’

Why did the Wehrmacht exhibitions generate much more public emotion than previous debates about the German past? For two reasons, according to Jureit. First, the participation of the Wehrmacht in Nazi crimes affected the private memories of a far larger swathe of the German population. But, second, because the debate about the first exhibition had ceased to be objective. After a certain point, there was a failure to distinguish between the Wehrmacht as an institution and individual Wehrmacht soldiers, i.e. over 18 million people. ‘Among veterans, but also within politically conservative and far-right circles, the opinion formed that in the first exhibition former Wehrmacht soldiers were being insulted wholesale.’

Realignments and mobilizations

Historian Ulrich Herbert explains how the controversy became a memorial ‘endgame’. ‘One can see the two Wehrmacht exhibitions as the conclusion of the classical phase of Vergangenheitsbewältigung (dealing with the past). Historiographic certainties emerged and political camps realigned in the process. The left-right distinction ceased to be based on the relation between capital and the working class, or between trade unions and employer associations, and now indicated respective positions in a specific controversy about the past. We can observe this happening in different forms in other countries, for example in the USA in the debate about memorials or in European countries about the colonial past.’

The Wehrmacht exhibitions also played a major role in the development of the far-right in Germany, argues Janosch Steuwer. After decades in which far-right demonstrations had rarely numbered over 200 participants, the exhibitions offered a new opportunity for political mobilization. The big NPD demonstration that met the opening of the first exhibition in Munich in 1997 was repeated across the country as the exhibition toured.

Wherever Neonazis marched, so did the anti-fascist Left. Julia Hörath reconstructs three such counter-demos: in Berlin in 2001, in Munich in 2002 and in Hamburg in 2004. But rather than underpinning a mainstream anti-Nazism, the primary effect of the counter-demos was to split the anti-fascist Left, a section of which rejected any such consensus.

This article is part of the 19/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 21 December 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Preparing for the good times to be over

A month into Russia's invasion, is the EU ready for the challenge?

Russia’s war on Ukraine is clearly an attack on the whole of Europe, but domestic responses are still stuck with the narrative of patriarchal solidarity and the concern for consumer comfort on the home front. Philipp Ther argues for active solidarity, and with it, to prepare for the end of the convenience Europe has known: it may hurt, but without it, the long-term losses to freedom and welfare are likely to be higher.

Reappraising Wallraff

Merkur 2/2022

In ‘Merkur’: why Günter Wallraff’s 1985 bestseller ‘The Lowest of the Low’ appears scandalous by the standards of today’s racial justice discourse – but remains absolutely worth reading for its searing analysis of the exploitation of labour in wealthy democracies.