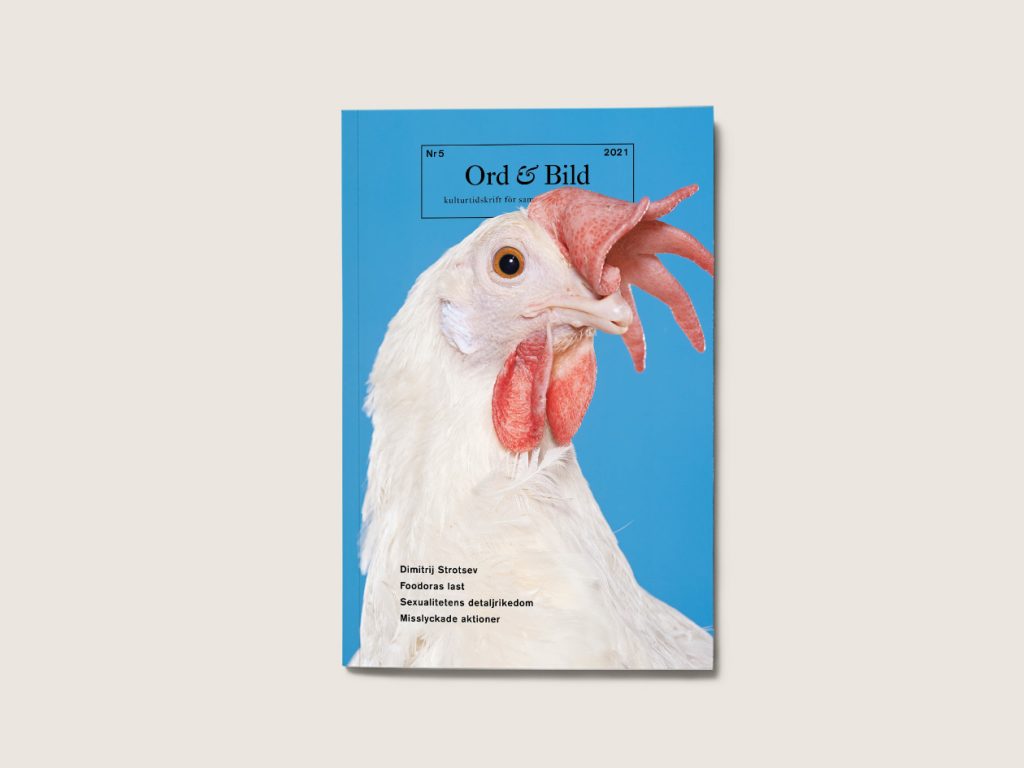

A profile of a hen graces the cover of the latest issue of Ord&Bild. There is another on the back cover and two more inside. Pictured against a blue background that evokes Renaissance portraiture, the hens stare at the viewer with gaze one could almost perceive as human. They have distinct characters and come from a series of 168 photographs by Hungarian artist Daniel Szalai.

The birds are genetically engineered individuals belonging to the breed Novogen White, whose eggs are used in the pharmaceutical industry for a range of medicines, including vaccine production. The animal exists to boost our immune system, but lacks an immune system of its own and could never exist outside the sterile conditions of the laboratory. Szalai’s photo series poses questions about mankind’s relation to nature and, by turning the spotlight on the hens, pays tribute to their ‘invisible labour’.

Work

Last year, the musician Anders Teglund published a critically acclaimed exposé of Foodora (more here). Now Teglund looks beyond his own experiences as a courier in an article on the shortcomings of trade unions in the gig economy.

The connection between delivering takeaways and making music might seem strange, he remarks, but the term ‘gig’ was how jazz musicians in the 1920s referred to a concert or a set. It is something entirely different from monotonous work executed for a single employer and can also apply to an article commissioned from a writer or any other type of freelance work.

Now the meaning of the word ‘gig’ has spread to services where workers don’t have a contract or continuity. Or, to put it bluntly: labour for which the employer takes no responsibility. For instance, ‘when a messenger delivers food through Foodora’s app Roadrunner or a person with a truck drives a sofa for a private individual via the app Tiptap’.

Through personal accounts from around Europe, Teglund exposes the problems posed by the traditional system of organized labour in Sweden. Does the ‘Swedish model’ primarily defend a certain kind of Swede? Teglund makes clear how invisibility serves the interests of platform employers. When companies offer food outside your door within ten minutes, no wonder they do not tell you who will make it possible or why it is so cheap.

Belarus

In October 2020, the Belarusian Russian-language poet Dimitry Strotsev was abducted on the street by the KGB, sentenced and imprisoned for 13 days. ‘I do not exist as a poet in Belarus!’ Strotsev explains to Ord&Bild after a recital at the Stora Teatern in Gothenburg. ‘Not for the ministry of culture. They have sent out an order that my books be removed from the libraries’.

Strotsev praises the sense of community in Belarus in 2020 and stresses the importance of support from abroad. ‘For me’, he says, ‘the most important thing to happen in 2020 were not the protests, but the new aesthetic solidarity that spread throughout the entire population … first there were queues of people, then chains of solidarity, not least the women’s marches. When we convened in central Minsk there was no aggression, but a common sense of joy that paradoxically coincided with the most terrible violence.’

Heritage

In a mix of personal account, archival material and reflection, Ord&Bild editor Ann Ighe writes about failed protests and empty spaces in the face of neoliberal urban development. Revisiting the squatting movement of the 1980s, she writes: ‘How did we – a bunch of punks and others at the time – relate to cultural heritage, to earlier activists?’

The district of Haga in Gothenburg never became an autonomous zone like Christiania in Copenhagen or Svartlamon in Trondheim. It was a dream that disappeared; some people have remained but the open spaces are gone. ‘We couldn’t stay, in fact many of us doubted we would be able to. But the community of direct action still exists.’

This article is part of the 2/2022 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.