I’m not, but all my neighbours are

In an insane game of geopolitical musical chairs, some post-Soviet European states try to cast themselves as Central, although they don’t feel quite the same way about their neighbours. Why won’t they just identify with the East? A pair of reads from opposite ends of the Union offers fresh insight into the discourse of Central Europe.

Obviously, I’m radically eastern. Growing up in the North-East of Hungary, the reality of life on the Ukrainian side of border was much closer to me than the constantly evoked ‘Austrian living standards’. Cross-border trade was the lifeblood of the region between the collapse of communism and EU accession in 2004. One didn’t even have to smuggle: legal imports of petrol, vodka or cigarettes would, when resold on the black market, sustain entire households. This difference in wages and prices both wrecked and maintained a special local economy.

But this informal economy wasn’t the only way in which the communities on both sides of the border were connected; ethnic, cultural and social ties also ran deep. The historical Satu Mare or Szatmár region, for example, is currently shared by Romania, Ukraine and Hungary. Although Hungarian nationalists have debated for over a century the 1920 borders designated by the Trianon Treaty, the ethnic, religious and cultural composition of the population has long been so mixed and intertwined that it is impossible to tell them apart. In a region like this, any border will be arbitrary – the real question is how people can live with them.

Throughout the 1990s, life here was organised around the border, defined but not dissected by it. But upon Hungary’s accession to the EU, a harder border was introduced, from one moment to another cutting the lifeline for many on the Ukrainian side. It also isolated those on the western side. Hungary’s poorest county was now forced to compete in a west-facing economy and culture, instead of operating in its accustomed geographical place in the East.

My confusion mounted as the slogans of accession told us that we were heading to Europe. At geography class I had been taught that Europe reached to the Urals and the Bosphorus.

Sculpture by Ilya Kabakov Photo by Ikiwaner via Wikimedia Commons. Adaptation: Eurozine logo has been placed.

It was around the same time that I left my hometown for Budapest, the bewildering metropolis where people would not make way for each other on the pavement. My new acquaintances would joke that I should carry a passport for my bi-weekly tours home. I felt more eastern than ever, but still didn’t understand why that should be a problem. Over the years, living in the self-declared ‘Centre of Europe’, I grew suspicious of ‘city folk’, even if I hadn’t held a shovel for a long time. My autoimmune reaction to the prejudice I knew to be toxic made me quite as bitter.

It was first in Vienna, on the brink of my thirties, that I first felt freed from the oriental stigma. Surrounded by all sorts of migrants, many with similar inferiority complexes, I felt safe and understood as never before. My new friends and I would merrily complain about our home countries while also missing them terribly, loving to mingle with a diverse crowd against the backdrop of an actually functioning welfare state – albeit not the most welcoming one.

This experience confirmed my long-held notion that Central Europe consists of one country and one country only: the uncanny abstraction that is Austria. One could also squeeze in Switzerland, if really necessary, just for being another neutral intermediary.

For something I claimed I couldn’t be bothered with, I spent a lot of energy avoiding the subject. The real reason was very simple: my strategy for coping with prejudices against the East was to fiercely identify with it. Debating the category would have interfered with this. But I couldn’t hold out forever.

By chance, a pair of reads now offers fresh insight into the discourse of Central Europe. In the Ukrainian journal Krytyka, Mykola Riabchuk reveals the exclusions coded into Kundera’s pivotal 1983 essay ‘A kidnapped West’. Establishing a ‘Central Europe’, Riabchuk argues, merely reinforces the stigma of the East:

‘Central Europe’ is a discursive life-belt that gives some nations a chance to be rescued on the secure board of the western flagship. But it fits only a few of them – Czechs, Hungarians, partly Slovaks who also hate to be ‘eastern Europeans’, and perhaps Slovenes who loathe being part of the ‘Balkans’.

Others need to extend the term, hyphenating it into ‘central eastern Europe’, like the Poles or Romanians, or inventing something else like ‘Nordic’ for the Balts, or ‘Mediterranean’ for the Croats, Montenegrins and perhaps Albanians. Bulgarians have no choice because the very term Balkans stems from the name of the mountains in their territory. And Ukrainians, Moldovans and Belarusians have to either go to ‘Eurasia’ (the new code-name for Russia and its truncated ‘sphere of legitimate interests’) or become a ‘new eastern Europe’, since the ‘old’ eastern Europe disappeared.

The game might be childish, but the stakes are high – as the example of Ukraine’s struggle for self-determination clearly shows. In this territorial contest, countries and communities are pitted against each other, either political adversaries, or as labour markets competing for capital, as it looks for cheap and insecure labour.

But on the opposite side of the Union, the idea of Central Europe means something rather different. Writing in Dublin Review of Books, Enda O’Doherty is more forgiving of Kundera’s nostalgia for the ‘lost culture’ of the small nations of the former Habsburg Empire:

Whether there is any inherent moral bonus that comes from simply being small, or having had to struggle to assert one’s right to national existence, is perhaps another question. But it is at least plausible to suggest that citizens of states which have been more minor players in European history might be more ready to see a construct like the European Union as a site of fulfilment (‘taking one’s place among the nations of the earth’) rather than as an institution which is valued only in so far as it can be manipulated to serve ‘the national interest’.

O’Doherty reviews the idea of Europe in the work of five twentieth-century writers closely associated with the idea of Central Europe: Zweig, Roth, Miłosz, Kundera and Nooteboom (the western exception). He finds them isolated with their pacifist and pan-European ideas amidst war and persecution, criticized for leaving homelands in search for security, offered moral support but no lunch money. This tension between ideals and their execution persists, even as the European populi, if rarely wildly enthusiastic about the Union, generally consider it in their best interests.

But the competition for Europeanness has its losers. The selling point that ‘I’m not eastern, but all my neighbours are!’ has real consequences, also for the East beyond Europe.

It might be better, then, to do away with the stigma itself. Were it less detrimental to be treated as the East – or as ‘peripheries’, as it is more commonly phrased – rivals might find better hobbies than playing this insane game of geopolitical musical chairs.

This editorial is part of our 7/2021 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 14 April 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

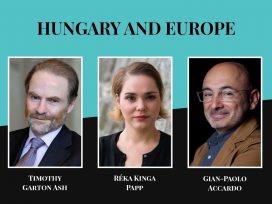

The legacy of division: dual book launch

Watch the discussion of authors and curators #EMCJ31

What is racism against eastern Europeans? And what did Viktor Orbán learn from Slavoj Žižek?

Are crises necessary?

Debates on Europe: Budapest & Beyond

As a historian his expectations are gloomy, but as a political writer his optimism is strategic: Timothy Garton Ash talks about the European Union’s internal flaws and debates whether crises and collapses are always necessary for renewal.