Texts without words

Textiles are more than just yarn – they are memory. Migrants pack them in their bags to recreate the homes they have lost. Burcu Sahin explores the timeless language encoded in stitching.

We settle down in the yard to shelter from the heat. This is Koza Han, the silk bazaar in Bursa, my mother’s hometown and, under our parasols, we sip Turkish coffee while my mother tells me about the bazaar. Built by a sultan in 1491, it was originally a market for trade in silkworm cocoons. Today, the shops sell silk shawls and fabrics. An engraved plate fixed to a stone wall describes how silk is made. The thread, it explains, comes from the cocoon that serves as a casing to protect the silkworm until it is ready to emerge as a moth. Silkworms feed on the leaves of mulberry trees, and the cocoon is made of thin thread that, when unravelled, can measure, as much as an astonishing 800 – 1200 meters.

My grandmother used to take in home sewing and, before I was born, my mother did the same. They would work through the night until dawn, sleep a few hours and then go about their daytime tasks of cooking and cleaning. In time, my mother migrated to Sweden, bringing some of her handiwork with her – unfinished embroideries that later made me pause and wonder. What was it that made their completion impossible? In the snowy Swedish landscape around us, the patterns looked alien. As a migrant, it is common to feel that, somehow, your body and the few possessions you have are incompatible with your new surroundings or your idea of how local people look.

I ask my mother about her early impressions of Sweden. She tells me how she woke one summer’s night and got up because it was light. She started to make breakfast but, looking through the window, realised no one was about. At last, she checked the time and found it was three in the morning. She had been used to dark nights and it took time to adjust to Nordic light.

Silk Bazaar of Bursa (Turkey)

Photo by Adbar from Wikimedia Commons Adbar / CC BY-SA

What do you pack when you migrate? Why bother with embroideries, hand-woven rugs and fine threads? Like my mother, these things had crossed borders but, unlike her, they were not looking for a place to call home but for a place to make into home. The British artist Maxine Bristow writes that objects we use as ‘stage sets for the routines of our busy lives’ end up being inscribed into social structures and relationships, acting as their silent participants. They bear witness to the unsayable and speak of what cannot be expressed.

I believe my mother brought with her to Sweden things with a significance so closely and immediately linked to the sense of being at home that they would make any place meaningful to her. Perhaps they also bore traces of a way of living she could not fully articulate in words, either written or spoken.

Many migrants are not permitted to retain their belongings or, indeed, control of their bodies. For example, Denmark’s 2016 legislation, based on a long-established Swiss practice, gives the authorities the right to confiscate asylum seekers’ possessions and valuables. When the law was voted through, the idea behind it was that selling these objects would raise funds towards financing the asylum application process. In Sweden, the right-wing Swedish Democrats have put forward a parliamentary motion arguing that a similar system should be implemented here. When moving from one country to another, what belongings should you be allowed to keep? Who will take account of the histories and memories your possessions bear with them? Are you permitted to stand up and tell the stories that explain why these things matter so much?

My mother sewed the curtains and bedspreads for our bedrooms – my sister’s and mine. She put lace doilies on tables and hung embroidered towels on hooks in the toilet. Touching the material, looking at the weaves and the stitches, made me realise that these things had been created elsewhere, in different circumstances. The children of migrants often ask parents or older relatives to tell them something about their lives before – but so much remains unsaid. A migrant fears the effects of passing on a legacy of memories and stories that may hold pain or trauma. On the other hand, they want the young to understand, and make their own, the political battles or convictions that drove them to migration in the first place. This can be especially problematic when the younger and older generations do not share the same language – very often literally. I will never know the precise truth of the many stories my mother told me. In time, however, it dawned on me that my mother and grandmother’s handiwork was a source of knowledge – stitches and patterns can be deciphered. This idea has grown on me: the language of fingertips and materials is tangible. It transcends spoken or written communication, but it can be interpreted. I came to realise that neither my grandmother nor my mother had been given access to education. They belonged to the many women in the world who earned and continue to earn their keep by sewing, at home or in a factory. I understood that their work and craft were often the only means by which they could document their existence and personal history. Their names will never appear in historical records. And now, I ask my mother to tell me about things back then because I have never learnt to sew – but do know how to write.

*

In her book Weaving the Word (1994)1, Kathryn Sullivan Kruger, argues in that we must extend literary history to include texts created, since ancient times, in the form of textiles. Kruger stresses that cultural change can be studied by learning to read textiles as though they were written text. Sewing and weaving are traditionally regarded as women’s work, which leads to the argument that women have long participated in the textual documentation of stories, myths and religious faiths by encoding symbols and images in their embroidery and weaving. Kruger explores how, in the hands of women, weaving becomes a tool used to inscribe personal and political messages into the weave. As the relationship between text and textile changes, incorporating the theme of weaving materials and processes into writing could serve to revive historical study, Kruger believes. This approach to literature, as well as to textiles, represents a break with tradition in the West, where concepts of art and craft have always tended to be distanced.

In their introduction to Feminism and Tradition in Aesthetics (1995)2, American philosophers Carolyn Korsmeyer and Peggy Zeglin Brand argue that an object’s aesthetic qualities have been described as wholly distinct from its instrumental, economic or political characteristics. Philosophers of art such as Clive Bell and R.G. Collingwood, had held that crafted objects could not be regarded as art, because they had been created with a practical end in view. Since then, several previously unknown women artists have been given recognition, sometimes posthumously, and their work has been exhibited in galleries and museums. But many remain undiscovered. ‘What cultural and intellectual frameworks inform our thinking about perception, beauty, art and culture?’ Korsmeyer and Brand ask. When expressed in these terms, the question of aesthetic judgement becomes a feminist concern.

Quipu Menstrual de la artista Cecilia Vicuña. obra site specific en Documenta14, 2017. Photo from TereQG via Wikimedia Commons TereQG / CC BY-SA

I once attended a performance given by the Chilean artist and poet Cecilia Vicuña, during which she sang sounds and lines from poetry, while linking herself to her audience with wool yarn. Since the 1960s, Vicuña has been working on installations composed of quipus, an ancient Andean writing tradition used by the Incas before the colonised. A quipu is a collection of woollen threads, or else of spun or plaited cords made from alpaca or llama pelts. Traditionally, the strands carried numerical values coded as knots. These knots worked according to a decimal system. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas, intent on extorting gold and silver from the native peoples, it is told that the Incas destroyed their textiles to prevent any record of their culture, knowledge and beliefs from falling into the colonizer’s hands. Vicuña calls the lost Inca tradition: ‘A field of images, erased by European occupation and colonisation but still accessible to those who seek the source of the sounds and languages of the landscape’. Vicuña looks to find, reinvent and transform the meanings of lost languages and materials. She returns to sacred or significant places to perform rituals but many of her installations also stage the disappearance of ancient practices (as she lets red alpaca wool drift away in winds or waves, for example). The threads form a way of approaching the history and memory of landscapes, lost peoples and languages. While searching out places they inhabited, Vicuña’s intention is to highlight the fact that exploitation is not in any way confined to the past. In works like Antivero (1981), she illustrates how, in the capitalist economic order, entrepreneurs drive up production in the name of profits, and turn to regions with a history of colonisation to recruit cheap labour and find places to dump waste. One of Vicuña’s installations comprises red threads spread out across a river in central Chile’s Colchagua province. Of this she writes: ‘Before it is polluted, the river wants to be heard’.3

The way in which Vicuña makes use of quipus reflect her anti-colonial and eco-critical views, while at the same time emphasising that her very reason for exploring this tradition can be found in the notion of transforming textiles into language. In her poem Word & Thread (1996)4, words are described as threads and threads as language. She writes with insights that display sensitivity to a spirituality linked to consciousness of history, community and vitality:

‘To speak is to thread and the thread weaves the world.

*

In the Andes, the language itself, Quechua, is a cord of twisted straw,

two people making love, different fibers united.[…]

The weaver is both weaving and writing a text

that the community can read.An ancient textile is an alphabet of knots, colours and directions

we can no longer read.’

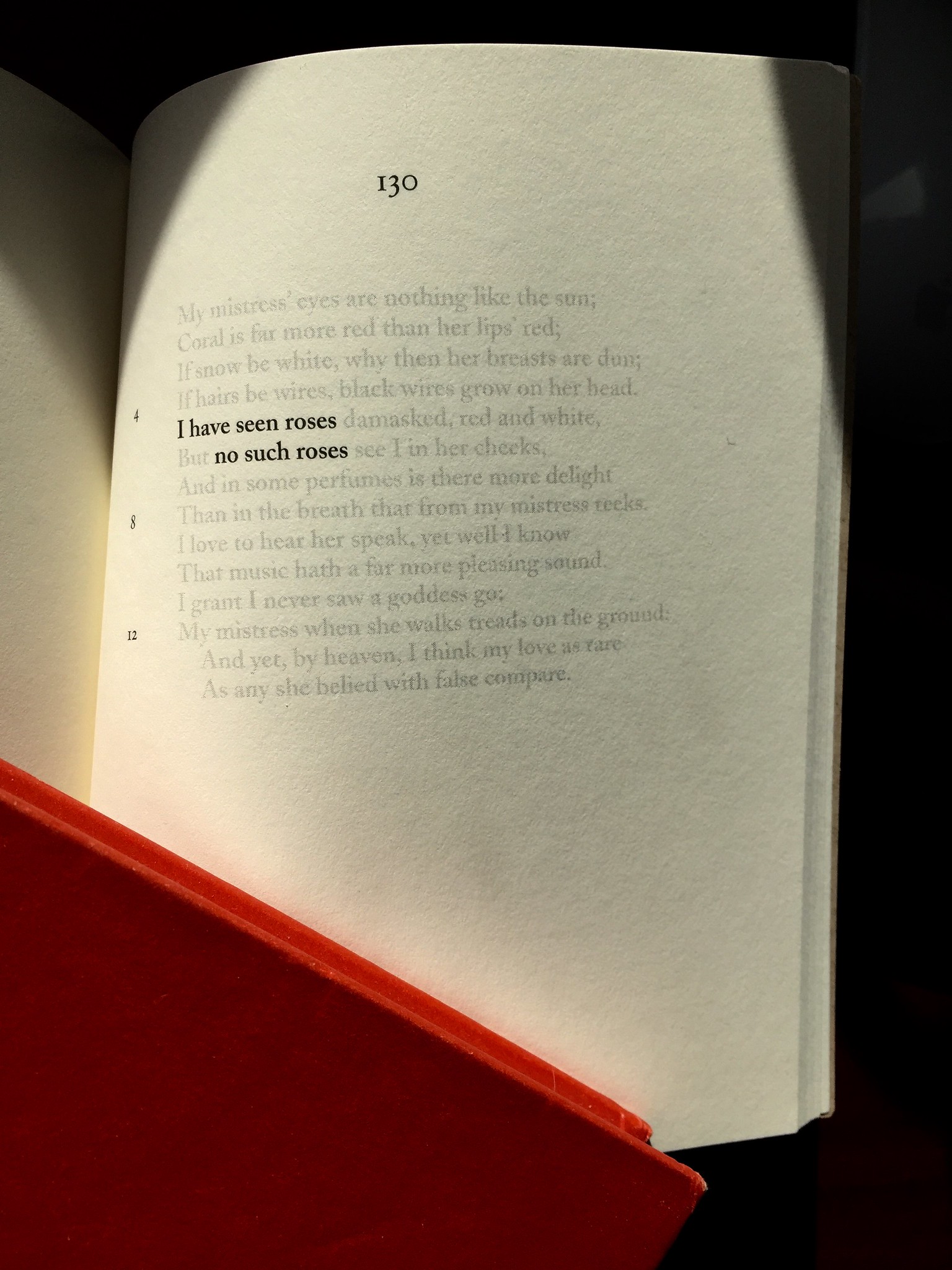

Net 130 Sonnet 130 in palimpsest From Nets, Jen Bervin

Photo by M C Morgan from Flickr

We can, yet we cannot, read textiles. It depends on how we understand the meaning of ‘readability’. The notion that textiles can be read represents a break with fixed categories and dichotomies: it asserts that, if seen from a different perspective, words and written knowledge can be conceptually redefined. In her Silk Poems (2017), American poet Jen Bervin writes about silk as a biological material and explores the intersections between writing and technology inherent in a piece of silk re-engineered into a biosensor. While preparing to write, Bervin consulted over thirty institutions world-wide: bioengineering laboratories, textile archives, medical libraries and silk production stations. In the closing research sample, she writes:

‘Silk, as a material, is compatible with body tissues; our immune system accepts it on surfaces as sensitive as the human brain.

In 2010, I visited Tufts University’s Bioengineering Department, where David Kaplan and Fiorenzo Omenetto were reinventing silk as a cutting-edge technological material in a new form: reverse-engineered liquefied silk. One facet of their remarkable research captured my attention: a silk biosensor in development, written in nanoscale on clear silk film. It was designed to be implanted in the body to sense shifts in target materials – blood sugar in haemoglobin, for example. The meaningful health content, the scale of the writing and the simplicity of the material astounded me.’

Bervin describes a way of reading the projection of the silk film after it has been illuminated with fibre optics. Once she realised it was possible to ‘texture’ silk and place the patterned material inside a human body, she felt inspired to speculate about what more could be written on it. She integrated the cultural history of silk, which stretches over some five thousand years, into her investigation of the body as a context for writing. As the poem begins, a cocoon cracks and a worm is transformed into Bombyx mori – a silk moth. The emergence of the creature is equated with the appearance of the poem. Bervin makes visible the accumulated time that has passed between the formation of the poem and the origin of silk production. The first silk threads were discovered in a cup of tea placed under a mulberry tree in China – Bervin’s lines and the thread in that teacup are therefore millennia apart. The poem evokes messages from the long distant past: fragments of silk excavated in Zhejiang; manuscripts on silk found in a burial chamber in Hunan province; inscriptions on silk, bronze and perforated paper resting on bamboo trays; magic writing on oracle bones and turtle shells. Slowly, a unified pattern emerges. The natural processes that create a silkworm cocoon are also linked to human biological functions devoted not to the creation of new life but to subjectivity, transformation and death:

M E M E N T O

M O R IM O R U S A L B A

M U L B E R R YB O M B Y X M O R I

M E

Critics have observed that Bervin’s work is preoccupied with the feminist view that the penetrability of the body is controlled politically and technologically. Both silk and the human body have specific histories and contexts but – by dissolving distinctions between inside and outside, body and fibre – Bervin’s poems reject the idea that materials can stay intact as incompatible constituents are intertwined. Bervin shifts the focus from the intended purpose of an implant (to keep track of some aspect of health, for example) and instead turns her attention to silk as a historical topic and a poetic theme. Her poems insist that distinctions between writing, textile and body are infinitesimally small, but that dissolution and fusion are a connected process.

If Bervin’s silk poems explore the interior of the body, Lenke Rothman approaches the same subject from the outside. Rothman is a Jewish-Swedish writer and artist, who has experienced literally being stitched together. When the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was liberated by the British army, she was one of the prisoners released. Aged sixteen, she was sent to Sweden to be treated in hospital for severe tuberculosis, returning there several times over a period of six-years. Rothman underwent operations, was stitched together after, and had to endure a series of treatments lying in a plaster cast. Lying on her back, she sewed pieces of paper and left-over fabrics, linked with safety pins. Her father had been an umbrella maker and sewing was an integral part of her childhood. In ‘Rain’ (1989)5, she writes about the time when her family was deported:

‘Before they took us away, on a lovely summer’s day in 1944, our sewing machine was driven away along the cobbled street. The noise it made stays with me, recurring like an echo of a catastrophe. Then, we didn’t understand that our extermination began with the sounds of our sewing machine on the cobbles.’

Rothman went to Italy to train as an artist. In her writing as well as her art, she returned to the theme of sewing. The Swedish academic Niclas Östlind interviewed her and describes how scraps of material, threads and stitching had always been part of her artistic world:

‘The stitch is in itself such an eye-catching element that one is inclined to see its presence as her signature. Piece by piece, materials are added together and held by the stiches to make a new set of connections – a kind of wholeness. If one sees it as wound or a scar, the canvas of the paintings seems like a body. It becomes skin and flesh.’

Rothman answers:

‘Thread turned into the thread with which I could sew to join past and present. But the stiches came from the surgeon’s stiches I had after one of the operations I had to undergo after the war because my body was ravaged by TB.’

Rothman’s work as an artist makes me think about the etymology of the word ‘text’. Derived from the Latin te’xo (‘weaving’) and te’xtus (a ‘woven thing’, ‘tissue’), it can also mean interweaving. There is a considerable body of philosophy and literary theory addressing the relationship between texts and textiles, with reference to historical and etymological variants, leading in turn to new definitions for both textiles and literatures. ‘All literary texts are woven anew out of old passages,’ the French literary theoretician and philosopher Roland Barthes writes in his essay ‘From Work to Text’ (1971).6

Yet metaphors and analogies based on sewing and weaving risk making invisible the women who, historically, worked with textiles. Victoria Mitchell, a British artist and academic, has pointed out that textiles risk being seen purely as abstractions and thus part of a logical system that privileges the autonomous thinking subject. Sewing and weaving are in danger of being turned into representations of something distinct from a craft that is tactile and physical. For Rothman, literature and art emerge at the point of intersection between tissue and weave, body and stitch, cloth and thread. Writing is not separate from, but part of, the body. The sound of the disappearing sewing machine fills and fragments it. But later, the body is mended with needle and thread. Rothman’s stitches hold the disintegrating body, connect it to a history of pain and struggle, but serve to heal the sorrowing mind.

Rothman’s thoughts about joining and mending connect her to the Native American writer Paula Gunn Allen, who writes about mythology, weaving and colonialism in The Sacred Hoop (1986):7

‘In the beginning was thought and her name was Woman. The Mother, the Grandmother, recognized from earliest times into the present among those peoples of the Americas who kept to the eldest traditions, is celebrated in social structures, architecture, law, customs and the oral tradition. To her we owe our lives and from her comes our ability to endure, regardless of the concerted assaults on our, on Her, being for the past five hundred years of colonialization. She is the Old Woman who tends the fires of life. She is the Old Spider Woman who weaves us together in a fabric of interconnection. She is the Eldest God, the one who Remembers and Re-members; and, though the history of the past five hundred years has taught us bitterness and helpless rage, we endure into the present, alive, certain of our significance, certain of her centrality, her identity as the Sacred Hoop of Being.’

The woman who ‘Remembers and Re-members’ reminds me of another passage in Vicuña’s poem Word & Thread, where she writes that words and threads act as channels to the centre of memory. They serve to link: ‘Is the word the conducting thread, or does thread conduct the word-making? / Both lead to the centre of memory, a way of uniting and connecting.’

The Woman/God in The Sacred Hoop is the spider weaving every living thing into its web which, in the Native American context, can be read both metaphorically and literally. When I reflect on mythology, and the meaning of sewing and weaving, the poem ‘Weavers of Worlds’ (1943)8 by the Swedish writer Moa Martinson and its first verse comes to mind:

As time dawned, we began to weave

a cloth that grew unendingly long.

We are the nameless Norns

whom the bards forgot in their song.

We sought our weft round the world,

found fibres in hemp, jute and rushes,

in flax, wool and in a readymade spool,

the silkworm in a mulberry tree

found one day in a scented wood.

The poem begins at the beginning of time itself, similarly to Gunn Allen’s myth. It is many things: a kind of Genesis, a song of praise and a call to battle. Invoking the Norns, it also becomes an incantation of the controllers of destiny, who lived at the foot of the mythical tree Yggdrasil and watered it, drawing on the Well of Fate close by. In Martinson’s poem, the Norns – goddesses who spin the threads of fate – are as yet nameless and unknown. The ‘we’ in the poem can be read as signifying the Norns, while also expressing the collective to which they belong. The poem continues to describe how ‘we’ weave for war, for the living, the church and the devil. The weave grows longer than the galaxy but fails to reach far enough to ‘shelter each freezing woman and man’. Still they continue to weave – but why?

By the piercing howls of the sirens of war

We weave for generations to come

Listening to blood’s siren song in our ears

As it murmurs of life, shelter and nurture.

Martinson speaks of self-sacrifice, caring, violence and brutality, but also of the unfulfilled promise that a time of rest and peace will come. Despite its immensity, the weave is insufficient. While depicting the work of the Norns, the poem progresses towards a collective history of women, homing in on their shared sense of order and limited freedom of movement.

Basuritas del fin del mundo (2012), Cortecía de la artista y Lehmann Maupin, New York. Fotografía de James O’Hern

Photo by TereQG from Wikimedia Commons TereQG / CC BY-SA

Women who mend and sew sorrows (their own and those of others) recur as a motif in ‘The Seamstresses of the Night’9 by Swedish writer Siv Arb. Like Martinson, Arb describes the labour but also the disappointment wrought by the broken stitches of a Utopia that never materialised:

At night the seamstresses work

as if their lives depended on it

changing and altering

patching and mendingAll these worn-out items

and outdated outfits

from a time that has passed

a Utopia that came apart at the seams

In these poems, sewing or weaving is not equivalent to writing, even though reference is made to the language, history and knowledge of textiles. Rather, the writers use images to express the grief, pain and work that comprise a large part of women’s history. Whether or not the seamstresses’ dreams become real, it is important at the very least to remember the women and their work.

I did not sew with my mother and grandmother, and I feel the disappointment of not having shared the experience with them. I remember starting to write so as to create a space for myself in a language close to the silence of tactile communication, which speaks in a different way. I remember, too, that I had to stop writing to practise what poetry had taught me about community. I never forget that women often have to take on tasks no one else wants, and that they do so without losing their will to fight or their eye for beauty – as the Swedish poet Birgitta Lillpers writes in ‘Industrial Memories’ (2012):10

In 1941 my father’s mother

embroidered a tablecloth

with precisely marshalled roses

and carnations

all in cross stich.She must have been stitched in the brightest possible light,

holding on to a most orderly idea of the beautiful

to her tightly-wound will to sew the flowers

and the leaves that surround them,

sewn patterns in pulled and drawn threads

in the extremely fine linen. Even cut work

on the reverse along the short sidesSewing with her mind tense with gratitude

Or tightening with fearThe initials of the year.

I exist

This essay was written with the support of the West Götaland Regional fund for essays and ambitious cultural journalism.

Kathryn Sullivan Kruger, Weaving the Word : The Metaphorics of Weaving and Female Textual Production, Rowman and Littlefield, 1994.

Carolyn Korsmeyer and Peggy Zeglin Brand (eds.), Feminism and Tradition in Aesthetics, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995

‘Antes de ser contaminado el río desea ser escuchado.’

Cecilia Vicuña, Word and Thread: Poetry, Morning Star Publications, 1996.

Lenke Rothman, ‘Regn’ (‘Rain’) 1989.

Roland Barthes, ‘De l’oeuvre au texte’ (‘From Work to Text’), Revue d’Esthétique, 3/ 1971.

Paula Gunn Allen, The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions, Beacon Press, 1986 & 1992.

Moa Martinson, ‘Världens väverskor’ (‘Weavers of Worlds’), 1943.

Siv Arb, ‘Nattens sömmerskor’ (‘The Seamstresses of the Night’), 1994.

Birgitta Lillpers, Industriminnen (‘Industrial Memories’), 2012.

Published 15 May 2020

Original in English

Translated by

Anna Paterson

First published by Ord&Bild, 3-4/2019

Contributed by Ord&Bild © Burcu Sahin / Anna Paterson / Ord&Bild / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The imprisoned Belarusian opposition politician Maria Kalesnikava has been in a critical condition since the end of November. In October she was awarded an honorary professorship at the University of Salzburg. The philosopher Olga Shparaga, a fellow member of the exiled Coordination Council, pays tribute to a feminist legend.