For men may come and men may go but I go on for ever

“The Song of the Tigris River” (quoted by Isabella Bird)

Of all that once was in this ancient land, the swirling River Tigris alone remains, singing in every eddy and ripple; or so imagined Isabella Bird in her 1891 travel narrative Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan. The Tigris, 1,180 miles long, originates in the Taurus Mountains at Lake Hazar, Kurdistan, and flows southeast through Turkey and past Baghdad to unite with the Euphrates River at Al Qurnah in south-eastern Iraq.

Isabella quotes this snatch of song about the river early on in her book as she makes her way by steamer to Baghdad. It is both a simple allusion to the incredible history of the area, which stretches back to c. 10,000 BC, as well as a very personal reflection on mortality. By the time that Isabella stood on the banks of the Tigris she was already an acclaimed traveller and travel writer. She had written books on America, American Religion, the Sandwich Islands, the Rocky Mountains, Japan and Malaya, and had struck up a firm friendship with her Scottish publisher, John Murray. She had been brought up in Edinburgh but was unable to contemplate the “undendurable climate” of the Isle of Mull, where her sister had settled. In 1886 she planned to ride across little known parts of Turkey and Persia, to visit Christian outposts and the ancient communities of the Armenians and Nestorians. She was struggling to come to terms with the death of her beloved sister and husband, whilst she herself was 59, and not in the best of health.

It must have been easy to watch this ancient river that had sustained civilisations through the ages, from ancient Nineveh to the tarnished splendour of Baghdad, and reflect on the transience of life.

Just over ten years later, another, much younger, traveller, Louisa Jebb, stood on the banks of the Tigris. She was also prompted to reflect on the nature of time by the eastern lifestyle and the meanderings of this ancient river. Louisa was one of a select number of women who took the agricultural diploma at Newnham College, Cambridge under the principalship of Mrs Sedgewick, and had formed a friendship with the adventurous Victoria Buxton (later Mrs Victoria de Bunsen although referred to as X in Louisa’s book). The two had decided to embark on a journey through Asia Minor, from Constantinople via Tarsus to the head-waters of the Tigris, sailing down to Baghdad, and returning to Damascus through the Syrian desert.

Louisa writes in By Desert Ways to Baghdad (1907) with the suave assurance of youth: “Ignore time and he is at once your servant: treat him with respect and he at once becomes your master.” However, this pithy piece of wisdom, dispensed in the prologue, is something that she doesn’t always quite believe. In an amusing exchange with X she writes:

“X” I said, “where do you think we are floating to?”

“Baghdad,” said X.

“I wasn’t thinking geographically,” I answered, “I was thinking whether it was Eternity of Oblivion. Being hurried along by the current gives me an uncomfortable feeling of not being allowed any choice as regards times, which I resent. Do you mind it at all?”

“No,” said X, “I feel that I have lost all conception of time, and that we are floating on, as it were, to Eternity.”

“Do you?” I said dubiously; “I feel it’s Oblivion we are getting to.”

“But we are only three days off Baghdad,” insisted X.

“Well,” I answered, “I devoutly pray that we may get there first.”

It is hardly surprising that the two travel books, By Desert Ways to Baghdad and Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan are very different. After the death of her husband in 1886 Isabella had resolved to travel again but not for her own health and amusement. She would visit medical missions in remote lands. The tone of her book is intelligent, she is not afraid of using statistics, and she has an appealing, dry sense of humour. As a contemporary wrote, she was a “very solid and substantial little person, short but broad, very decided and measured in her way of speaking.” Or in her way of writing, one might add. Louisa, in contrast, speaks with a fresh, occasionally idiosyncratic voice. Her personality dips and dives through the narrative, taking it to peaks of philosophy, or, just as easily, lowering it into “untrammelled manners” and “emblems of all the great abiding truths” with barely a batted eyelid. It is a slightly surprising book for a woman to write who took an agricultural diploma and then went on to be instrumental in the establishment of the Women’s National Land Service Corps and the outstanding pioneer of the small-holding movement, or at least its revival; but of course practicality and creativity need not be mutually exclusive.

Louisa’s prologue tackles head-on any apparent inconsistencies. She writes that Victoria, “had unearthed me from a remote agricultural district in the West of England with the idea that contact with the agricultural labourer would have fitted me for dealing with the male attendants who were incident to our proposed form of travel.” From the beginning, it all feels like a bit of a joke. The women decide on their route with the aid of a ruler, pencil and mutual desire not to go anywhere near the sea. “That will do for a start,” says Victoria, “we can fill in the details when we get there.” It is this sense of camaraderie and mutual endurance that gives Louisa’s book an appealing edge. Louisa writes about her indomitable companion: “The worst of X was that you never knew whether she was laughing at you. It is most uncomfortable position, which men as a rule resent. But I was another woman, and took it philosophically, especially as X accused me of the same failing.”

Bird, in contrast, has no female side-kick and chooses to write in an epistemological form. She did, however, have the escort of a 38-year-old widower, Major Sawyer of the Indian Army, who is referred to as M– in her book. He was a military surveyor on a secret reconnaissance mission to ascertain both the extent of Russian infiltration in the Middle East hinterlands and more precise geographical data about them. For obvious reasons, not least that the Indian War Office vetted her book before it was published, Bird mentions him only rarely. It seems likely though that Bird would have preferred to travel alone as she had in the past. She viewed any companion as “an infringement on my liberty”, at least according to Pat Barr in her 1988 introduction to Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan, but the area was exceptionally difficult for a European woman to visit alone. Isabella and the Major became “good comrades”, although when they finally parted after their second expedition at Burujird, Isabella privately expressed her relief that the major would no longer rouse her at dawn with his call, “To boot and saddle”.

The two accounts also differ in their descriptions of place. Bird records her impressions of Baghdad, “which are decidedly couleur de rose“, with good humour and a fine eye for detail. Her long sweeping sentences build up an intensely vibrant scene, enlivened by her dry interjections.

The splendour of the East, if it exists at all, is now to be seen in the bazaars. The jewelled daggers, the cloth of silver and gold, the diaphanous silk tissues, the brocaded silks, the rich embroideries, the damascened sword blade, the finer carpets, the inlaid armour, the cunning work in brass and inlaid bronze, and all the articles of vertu and bric-a-brac of real and spurious value, are carefully concealed by the owners, and are carried for display, with much secrecy and mystery, to the houses of their ordinary customers, and to such European strangers as are reported to be willing to be victimised.

[…]

The natural look of a Moslem is one of hauteur, but no words can describe the scorn and lofty Pharisaism which sit on the faces of the Seyyids, the descendants of Mohammed, whose hands and even garments are kissed reverentially as they pass through the crowd; or the wrathful melancholy mixed with pride which gives a fierceness to the dignified bearing of the magnificent beings who glide through the streets, their white turbans or shawl head-gear, their gracefully flowing robes, their richly embroidered under-vests, their Kashmir girdles, their inlaid pistols, their silver-hilted dirks, and the predominance of red throughout their clothing aiding the general effect. Yet most of these grand creatures, with their lofty looks and regal stride, would be accessible to a bribe, and would not despise even a perquisite. These are the mullahs, the scribes, the traders, and the merchants of the city.

Jebb tends to prefer a dramatic, poetic style, particularly when it comes to describing such a historically resonant place as Babylon:

We wandered amongst the huge ruins, balancing ourselves on the edge of low remaining walls and clambering from one courtyard to another. A jackal darted from under our feet with a shrill bark; he was answered from behind distant walls by innumerable hidden companions. An owl flew out of a dark corner and perched, blinking, a little way off; a great black crow hovered uneasily overhead. The broad walls of Babylon were indeed utterly broken, and her houses were indeed full of doleful beasts crying in her desolate houses; it was indeed “a dwelling place for dragons”, an astonishment, and an hissing without an inhabitant. Shamash, the Sun-God, was nearing the western gate of heaven. The gate-bolts of the bright heavens were giving him greeting. The Euphrates and its wooded banks lay between us and the horizon; above the river-line we saw a row of jet black palms in an orange setting, and below it a row of jet black palms standing on their heads in the rippled golden water.

That is not to say of course that these western men and women travelled by themselves. They were dependent on a number of different local men, a number of whom are sketched in detail by both Bird and Jebb. Bird is disparaging about her native servant, Hadji, who uses exasperatingly pious phrases to cover all his shortcomings. Jebb is equally annoyed by a number of her employees, going so far as to label one particularly malevolent kalekji “The Evil One”. Faced with his intransigence, she resorts to pointing a pistol at him until he rows. “Greatly to my astonishment,” writes Jebb, “The Evil One appeared to believe in the possibility of bloodshed and set to work at the oars. All the rest of the day I sat with my revolver at his head. It was a most fatiguing, if effectual, process.” Conversely though, Jebb has nothing but praise for a noble Alabanian Turk called Hassan who, “looked every inch the gentleman he was”.

Isabella and Lousia converged on Baghdad from different directions. Bird took a steamer from Basra, on the Persian Gulf and headed northwest. She writes: “In spite of the shallows at this season, the Tigris is a noble river, and the voyage is truly fascinating. Not that there are many remarkable objects, but the desert atmosphere and the desert freedom are in themselves delightful, the dust and debris are the dust and debris of mighty empires, and there are countless associations with the earliest past of which we have any records.” She passes time staring out at the banks, mentioning with a certain laisser-faire, “The first object of passing interest was Kornah, reputed among the Arabs to be the site of the Garden of Eden.” She then proceeds, “the night was too keenly frosty for any dreams of Paradise.”

Bird’s only mild adventure on the Tigris came when the steamer ran aground “with a thump” injuring one paddle wheel and obliging them to stay for part of the night near the ruins of the ancient palace of Ctesiphon whilst the boat was repaired. It was hardly a tragedy, for “its gaunt and shattered remains have even still a mournful grandeur.” All her grand adventures were to be played at overland after Baghdad. Louisa and X, in contrast, travel southeast down the Tigris to Baghdad, after an overland journey through Anatolia. The Tigris section of Desert Ways is called, rather accurately, “Down the Tigris on Goatskins”. So, you have the younger, inexperienced women heading down the Tigris on goatskins whilst the renowned, older woman heads up the Tigris in the comfort of a steamer. It is an amusing comparison, which undoubtedly says more about the relative development of the north and south portions of the Tigris than it does about the respective women’s priorities.

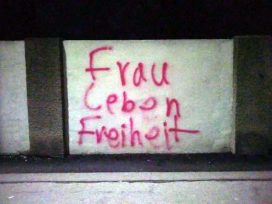

One theme that the women share, however, is the obvious one. They are women travellers at a time where British women did not even have the vote. A clergyman’s daughter, Bird was encouraged with her practical philanthropy, but hardly expected to go exploring little known corners of the world by herself. More importantly, these women travellers were visiting a land of harems and chadars: “It had not occurred to me that I was violating rigid custom in appearing in a hat and gauze veil rather than a chadar and face cloth, but the mistake was made unpleasantly apparent,” writes Bird, about her experience in Aimarah. Women, on the whole, stayed within buildings, making Louisa and Isabella’s journey a very masculine experience. “For men may come and men may go”: but women on the whole couldn’t, unless they were western women ready to defy convention (western and eastern).

Lousia and X, however, had one major advantage over Bird though: rumour spread like wildfire that they were western “Princesses”. The inferiority of their sex could not quite be forgotten, but it was at least mitigated by their apparently illustrious pedigree. Welcoming parties were sometimes sent out to meet them, a far cry from the treatment often meted out to foreign women (or any woman). In nearby Tehran, Mary Sheil, the English ambassador’s wife, was relegated to the goods train when her husband made his triumphal state entry. But how had such a rumour come about? Louisa explains:

“We had left our cards on the officials at the Konak. Now X’s Christian name was Victoria, and her address printed on the card was Prince’s Gate. To the Turkish mind this was conclusive evidence that she was a relation of the great Queen, and instructions for our suitable reception were accordingly telegraphed on. At Adana we found ourselves indisputably ‘daughters of the King of Switzerland’,” It was of no use denying it: “naturally we wanted to preserve an incognito.” Of course, Louisa and X found themselves explaining why they had no husbands, a subject on which they mixed a dry sense of humour with a healthy desire to preserve their own social standing and security: “In England the ladies do not care about husbands. In that country they rule the men. If anything were to happen to these ladies, the Queen of England would send her soldiers out here to revenge them.”

Bird is not quite so keen to make a joke about the relationship of the sexes, imbued as she was from youth with conventional social and moral Victorian standards. She was elected the first woman fellow of the Royal Geographical Society but had no real taste to become an apologist for the women’s movement. Pat Barr writes that she “viewed her own original life as something of an unnatural aberration for a mere woman” and that her later travels could be at least partly explained by the fact that she didn’t wish to become enmeshed in “causes”. It is certainly interesting that whilst ensconced in British domesticity she suffered a complex collection of maladies, but was in her element when enduring some of the toughest conditions known to man. Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan is the first book in which Bird makes frequent reference to her Christian beliefs, perhaps, as Pat Barr suggests, because it was the first time she had been confronted with so much evidence of the “fanatical Moslem oppression of women”. She offers sensible advice about the difficulty of mission life in the Middle East, especially for single women, which was not particularly heeded by church societies back home. Hers is a political book, in the sense that it is a repository for valuable information, historical, social and political. Jebb, in contrast, doesn’t really seek to advise or inform. She is less analytical than Bird, taking away from the East a more mystical, personal awareness of time and the value of silence.