‘There are either heroes or enemies, with no in-between. There is no room for indulgence or softness – just demands, judgments and relentlessness.’ How war makes a taboo of pleasure and the erotic.

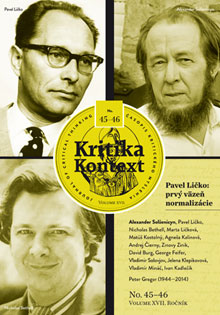

Pavel Licko was a partisan in the Slovak National Uprising of 1944, a member of the Communist Party of Slovakia, a translator from Russian and English, and in the 1960s he wrote for one of the most important Czechoslovak cultural journals, KultÚrny zivot. As a journalist, in 1967, he visited the well-known but not yet famous Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his enforced internal exile in the provincial city of Ryazan. The result of that rather adventurous encounter was Licko’s essay “One Day With Alexander Isayevich Solzehitsyn” published in KultÚrny zivot and eventually translated into many languages. As an expression of trust and friendship, Solzhenitsyn asked Licko to smuggle to Czechoslovakia and eventually to the West the manuscript of The Cancer Ward – the work that made Solzhenitsyn famous and helped him to win the Nobel Prize in 1970 and led to his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1974.

Licko was also the first person to be arrested in Slovakia following the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. His imprisonment during 1970-1972 was related to his contacts with and his article about Solzhenitsyn and the publication of The Cancer Ward in 1968 in Great Britain. A month after his release from prison, he was the focus in March 1972 of a fabricated documentary film broadcast on Czechoslovak television, where he was accused of being a British agent, cooperating in smuggling dangerous literature to the West and being an enemy of Husk’s Communist regime. This was the last blow that led Licko to his self-imposed isolation, both for not wanting to compromise the position of his friends being seen in his company and out of fear of being arrested again. Needless to say, most of his former friends and colleagues did not seek his company.

Licko was also the first person to be arrested in Slovakia following the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. His imprisonment during 1970-1972 was related to his contacts with and his article about Solzhenitsyn and the publication of The Cancer Ward in 1968 in Great Britain. A month after his release from prison, he was the focus in March 1972 of a fabricated documentary film broadcast on Czechoslovak television, where he was accused of being a British agent, cooperating in smuggling dangerous literature to the West and being an enemy of Husk’s Communist regime. This was the last blow that led Licko to his self-imposed isolation, both for not wanting to compromise the position of his friends being seen in his company and out of fear of being arrested again. Needless to say, most of his former friends and colleagues did not seek his company.

Clearly, Licko was a tragic figure, because the last twenty years of his life following his imprisonment he was harassed by the Communist regime, isolated and out of work, and was not able to or had no strength to write anything about his experience or existence. It was thanks to his wife Marta, also a journalist and translator from Russian, who was his dedicated companion and helped Licko to survive these difficult times of the post-1968 Normalization period (1969-1989). We want to thank Marta Lickov for her help and for letting us go through her archives while preparing this issue. In this issue, you can find a recent interview with her where she depicts the travails her husband and she herself experienced during the period of Normalization.

The experience in prison weakened and scared Licko to the degree that he never recovered mentally or psychologically. He died forgotten even in his native Slovakia in 1988, less than a year before the fall of Husk’s Communist regime. And yet, his smuggling of Solzhenitsyn’s book and his article about the Russian were both important factors for the Nobel Prize in Literature awarded to Solzhenitsyn in 1970. As the star of Licko gradually faded even in his native Slovakia, the Russian writer became world famous. Hence, the life and fate of Pavel Licko are connected to Solzhenitsyn not only through his article and the publication The Cancer Ward that led to imprisonment and isolation.

Solzhenitsyn became famous not only as a writer and critic of the West, but eventually, rather infamously, as a Russian nationalist crusading for the renewal of Russia’s soul. On this strange path he gathered all the elements of a past reactionary rhetoric and vocabulary, including anti-Semitism. To Solzhenitsyn’s dismay, the new corrupt and demoralized Russia of the 1990s was not interested in his antics of restoration of orthodoxy and nationalism. The path from a writer, dissident, and critic of the West and eventually to a rabid Russian nationalist is one of the great and controversial stories of the 20th century. That a part in this story was played by a Slovak intellectual, Pavel Licko, is also significant. However, the building of his own monument to his past heroism and feeling of being a victim of conspiracy led Solzhenitsyn to accuse Licko of acting on his own in helping the publication of The Cancer Ward. Yet, the correspondence between the two men clearly indicated that Licko acted strictly according to the instructions that he received from Solzhenitsyn. Licko both suffered for helping Solzhenitsyn while the Russian writer’s accusation of Licko undermined the legacy of the Slovak.

This issue is thus divided into three sections. The first offers a short overview of Licko’s life by Matu Kostoln who in 1997 dedicated his MA thesis to Pavel Licko. Then follows an interview with Licko’s colleague and friend from Kultrny zivot Agnea Kalinov about his arrest and the ordeal in the 1970s.

The second section is about the relationship between Licko and Solzhenitsyn, starting with two famous articles published about their meeting as well as excerpts from their correspondence. This is followed by excerpts from memoirs by Nicholas Bethell about publishing The Cancer Ward in 1968 and the accusation in England of Lord Bethell and Licko being KGB agents. A footnote to this accusation is the paradox that Licko was sentenced in Czechoslovakia around the same time, accused of being the agent of British intelligence services. This section ends with a reflection on the research of the Licko dossier by Andrej Cierny who helped put this issue together.

Finally, the last section is a glimpse into the controversial legacy of Solzhenitsyn himself. From his metamorphosis from a dissident writer, émigré and critique of the West to a deluded saviour of the Russian soul whose services the Russia of the 1990s was not interested in accepting. The section starts with excerpts from a critical biography by David Burg and George Feifer. It is followed by Solzhenitsyn’s brave letter to the Soviet Writers Union from 1969. Following is his famous Harvard University lecture from 1978 with his anti-Western bravado. Finally, there are two articles reflecting on Solzhenitsyn’s legacy by those who at first admired him but were gradually disillusioned and dismayed by his words and actions: writers from Russia like Vladimir Solovjov and Jelena Klepikovova or Russian émigré writer Zinovy Zinik. From the perspective of Solzhenitsyn’s evolution the accusation of Licko illustrated yet another example of Solzhenitsyn’s paranoia and selfdelusion that marked the last decades of the famous writer’s life.

At the end, you will find two unique texts about Solzhenitsyn written in 1974 by two Slovak authors who stood at that time at different ends of the political spectrum. A prominent writer, Vladimr Minc, was then director of the heritage institution Matica Slovensk as well as a Member of Parliament, an institution that had no real power. His text is a rabid accusation of Solzhenitsyn himself as well as his work. It was published in the Communist daily Pravda and concurred with his reputation as being one of the most prominent ideologues of the Normalization. The deceit of the text is heightened by the fact that the readers of this acerbic text could not confront it with what Solzhenitsyn wrote or did because his books like Cancer Ward or Archipelago Gulag were, understandably, not published in Czechoslovakia and he was generally presented by communist propaganda as the arch pariah of the Soviet Union. A poignant and deservedly harsh critique of Minac’s text exists from the pen of the writer and dissident Ivan Kadleck in his letter to Michal Gfrik from summer 1974 and published in 2010. When he wrote the letter, Kadleck had long been sacked from Matica Slovensk (he founded and edited from 1969 until 1971 the journal Maticného ctania). He lived in his native Pukanec, unemployed and isolated. At that time, he was saved from total isolation by Czech intellectuals and particularly Ludvk Vaculk who published Kadleck’s text in samizdat. Unfortunately, Kadleck is no longer with us; he passed away in July 2014. And so this republished text is a farewell to this great writer and also a brave, decent and tested human being.

The last section of this issue is an obituary for another great man. In March of this year the writer, aphorist, and poet Peter “Pierre” Gregor passed away. He regularly contributed excellent aphorisms to Kritika & Kontext. We also published a profile in 2004 (2-3) of this extraordinary man, who spent the first year of his life in Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Published 9 December 2014

Original in Slovak

First published by Kritika & Kontext 45-46 (2014) (Slovak version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Kritika & Kontext © Samuel AbrahÁm / Kritika & Kontext / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

‘There are either heroes or enemies, with no in-between. There is no room for indulgence or softness – just demands, judgments and relentlessness.’ How war makes a taboo of pleasure and the erotic.

On the documentary poetry of Jonas Mekas; multi-voiced personalism as literary genre; and the history of the Fens as ecological morality tale.