At the latest Eurozine conference of European editors of cultural journals in November 2018, an English participant remarked, a bit puzzled, how only in central Europe do people still talk in all seriousness about – and even quarrel passionately over – the role, place and responsibility of intellectuals. First, I felt slightly embarrassed recalling that Kritika & Kontext, the journal I founded in 1996, had devoted a whole issue to ‘The Intellectual and Society’. The debate then was both serious and passionate and, rereading it now, seems still valid today. Perhaps after all there is a special place for intellectuals in the heaven and hell of central Europe.

The intellectual who occupies centre stage is a long central European tradition, starting in the 19th century during the revolutionary and romantic eras, when artists and intellectuals – many were both – were instrumental in the various national awakenings and drives for self-determination, self-glorification and sometimes self-destruction. To this day, the region’s national figures are artists and intellectuals like Kossuth, Széchenyi, Petőfi, Palacký, Mácha, Masaryk, Mickiewicz, Sienkiewicz, Paderewski, Štúr, Lajčiak and Štefánik. These are the heroes that young Hungarians, Czechs, Poles and Slovaks read, recite and admire. Or should…

Albeit, these intellectuals managed to awaken both demons and angels among their compatriots. Their glorious and tarnished legacy is still charged with emotion and controversy and has pushed intellectuals to the forefront of events, especially during times of crisis and political turmoil.

Solna Centrum (Stockholms tunnelbana), Stockholm, Sweden. Photo by Dimosthenis Papamichail on Unsplash

Pity a country that needs heroes

The position of the intellectual in central Europe today is quite marginal and muted. One way to understand it is to examine the legacy of two towering figures, Václav Havel and Viktor Orbán, who represent diametrically opposed reactions to the post-communist politics which followed 1989. The choices and legacies of both figures leave contemporary intellectuals in a quandary when addressing the politics of their respective countries. I propose an alternative, illustrated by the deeds of an Austrian intellectual and editor, Walter Famler. But first, let us compare the status of intellectuals in the west and in central Europe and then, quoting from a 1996 debate in Kritika & Kontext, define the concept of the intellectual and the options available during and after the communist era. In the West, the term ‘intellectual’ has been viewed with suspicion since Julien Benda’s damning book La Trahison des Clercs (1927) blamed intellectuals for all the ills of the modern world. Democratic societies are slightly uncomfortable with intellectuals. It is stable democratic institutions and not heroic intellectuals that are supposed to symbolize a grounded political order. Brecht’s remark that one should pity a country that needs heroes works precisely because such countries are in a dangerous and dysfunctional state and heroes-intellectuals are sought and catapulted to the forefront in order to save it.

In recent decades in the West, in a poignant twist, indicating an almost central European malaise, there emerged the category of ‘public intellectual’. These individuals enter the political discourse as the political climate is becoming more and more unpredictable, as the dark demons of the past in the form of nationalism and neo-fascism feel confident enough to venture back in a variety of populist disguises to the public square of Western Europe and North America. Curiously enough, a number of these public intellectuals have spent an extended time in and have written about central Europe. Tony Judt, Timothy Garton Ash, Anne Applebaum, Timothy Snyder directly, and Bernard Henri-Levi, John Gray and Roger Scruton from a distance – but all with great interest – have examined the aftermath of fin de siècle central Europe where, according to some, all the important ideas and ideologies of the 20th century emerged. By default, these still define the present century which, so far, has offered no new ideas, merely regurgitated the old ones. And so these intellectuals, knowing the genesis of demons and angels in central Europe, are able to eloquently analyze developments on both sides of the Atlantic. They are aware of the irony that while central Europe is giving up on the virtues of western liberal democracy, the region’s worst impulses are gradually infecting the West.

In the midst of the current political instability, the present intellectuals of central Europe seem powerless in the face of regimes driven by nationalism, bigotry, populism, and anti-western and anti-liberal rhetoric, led by leaders with authoritarian impulses. The state institutions and independent media that should provide checks on the powerful are increasingly under threat, or in the pay of politicians and oligarchs. The space open to intellectuals is narrowing, their influence dwindling.

Why, then, write about the intellectuals of central Europe if they do not provide any of their traditional guidance? Why not just follow politics, both European and domestic, and expose the excesses of the extremists – the truly deplorable ones? One reason is that the current status of intellectuals is indicative of the condition of central Europe. The other is that today’s grave situation might yet deteriorate further, and when we finally hit the bottom, central European intellectuals will likely become a sought-after commodity again.

Exit, voice or loyalty

Approaches to understanding the status and definitions of intellectuals are manifold. In Kritika&Kontext (2/1996) we asked a distinguished Slovak, Czech and western intellectual the following:

What is the proper role of an intellectual in society? To what extent does this role depend on an intellectual’s self-selected path and to what extent upon the demands and challenges which society presents? What are the conditions for an intellectual to engage in ‘exit, voice or loyalty’, and what consequences do such choices entail?

We were referring to the popular terms coined by Albert O. Hirschman which were applicable to both economics and politics. ‘Exit’ meant choosing for various reasons not to criticize or challenge the regime, and to decide on internal or external exile instead. ‘Voice’ meant to openly challenge the regime, bearing the consequences in order to stand by one’s principles. The most intriguing is the concept of ‘loyalty’, which could range from supporting the powers that be, actively joining politics to the point of betraying one’s principles by becoming a sycophant or, even worse, misusing power for one’s own self-aggrandizement.

In the same volume of K&K, we then defined who is and who is not an intellectual. The crucial focus in the debate was the issue of autonomy, or insisting on the ‘choice’ that an intellectual has while deciding on his or her actions:

The intellectual is not defined simply by intelligence, but by their critical stance towards the status quo. Accordingly, a brilliant mind which loyally and uncritically serves the established order, however benevolent that order might be, is not an intellectual at all. Being an intellectual involves public engagement…

However, it is not a preordained, unconscious fate that the intellectual must follow, but a personal choice. … While it is true that the intellectual’s role as a ‘social conscience’ or ‘devil’s advocate’ implies the responsibility to defend the defenseless, prod the lazy, and admonish the tyrants, this role presupposes a prior obligation on the part of the intellectual to his or her obligations and principles. Thus, for society to insist that the intellectual is always and everywhere obliged to exercise the option of ‘voice’ is as much a violation of his or her autonomy as the censure of any tyrannical regime. Because both are necessary to the cultivation of the intellectual’s ‘critical stance’, the values of autonomy and responsibility are mutually dependent.

It is thus unfair to burden intellectuals with the fate of their society. Their autonomy to choose whether to be engaged or to withdraw into privacy is essential. Also, the conditions differed before and after the fall of the communist regimes in central Europe. One option was to enter politics and still try to remain an intellectual, as was the case for Václav Havel. The other has been to embrace any means to gain and sustain power, as has been the case with Viktor Orbán. In terms of the three options ‘exit, voice or loyalty’, Havel insisted on remaining a voice while entering politics, compromising both in an irreconcilable struggle; Orbán perverted loyalty through metamorphosis into a Leviathan.

Václav Havel, a pre-Machiavellian

Before 1989, Havel was Czechoslovakia’s pre-eminent dissident, imprisoned several times in the 1970s and 1980s. The communist regime failed to break or silence him, while Havel admonished the regime through countless proclamations, statements and articles, the most famous one being ‘The Power of the Powerless’. As a co-creator of Charter 77, he and other dissidents held the communist regime accountable for upholding the human rights proclaimed and undersigned by its leader in Helsinki in 1975. He was involved in politics without the need to compromise with the country’s rulers, following his conscience alone through what he called ‘living in truth’. He was the hero that his ailing society needed. After the fall of the communist regime in November 1989 he was catapulted into government, becoming the president of Czechoslovakia.

Havel confronted two regimes, communist and democratic, using the same approach for both. And here lies a problem for the intellectual. Entering democratic politics required a different strategy from that of being an independent voice admonishing the bankrupt communist regime before November 1989. He insisted on remaining an intellectual throughout. His concept of ‘living in truth’, standing above politics, won him praise, respect and support among many, both at home and abroad. However, in terms of politics it had tragic consequences for Czechoslovakia.

From the point of view of political theory, Havel’s politics after 1989 was reminiscent of a pre-Machiavellian view of politics. Writers of politics before Machiavelli stressed what politics should be like – principled, idealistic, devout and God-fearing. It disregarded the dirty, cynical politics prevalent in reality and hence did not confront it directly. In a way, Havel’s living in truth and power of the powerless is reminiscent of Thomas More’s Utopia – not a way to change a corrupt regime, but a vision of what ideal politics should be like. And facing a real political challenge, Intellectual/President Havel simply exiled himself from his responsibility.

One example of Havel’s failure was during the break-up of Czechoslovakia. Facing the division of the country of which he was the president, he simply deserted the sinking ship. Yet just a year earlier he had promised to stand and confront the separatists. Being an intellectual and not a politician, he refused to fight for his country despite the fact that the majority of Czechs and Slovaks were evidently against the division. Rather, he left the decision to the cynical prime ministers of the Czech and Slovak parts of the federation who, without calling a referendum, divided the country.

For an intellectual in politics, it was natural to desert politics in the face of political confrontation. And as an intellectual he had no qualms about becoming the president of the Czech Republic after the break-up of Czechoslovakia. The time of dirty politics ceased and he could become again, in a different country, an intellectual overseeing, from above and from a distance, real politics.

Petr Pithart, a fellow dissident and politician, called Havel a statesman without being a politician. I always liked that description because it absolved Havel’s political failings while preserving the aura of a president-philosopher. However, reflecting on Havel’s political responsibility, it does not make sense. One cannot become a sports champion without being a sportsman, a top surgeon without studying and practicing medicine. A statesman is the crowning achievement of a successful politician. Havel remained an intellectual in politics, paralyzed when it came to preserving Czechoslovakia.

Machiavelli has a poignant take on this type of idealistic politician, as valid today as it was in his time. He writes that if a virtuous and decent politician is surrounded by a society that is immoral and corrupt and he insists on keeping the moral high ground, he will be removed by those surrounding him and replaced by those who have no scruples. The solution is to lower one’s own moral standards in order to preserve one’s position and thus be useful to one’s society. Of course, this does not mean becoming as immoral and corrupt as those who surround you. Finding some middle ground is an art of politics, the domain of a true statesman.

Most importantly, Havel affected almost all central European intellectuals who saw in his stance towards and confrontation with the routine and often corrupt politics of post-communist society a virtue to be admired and emulated in deeds and speech. It effectively, I would argue, paralyzed these intellectuals in their idealistic approach to politics as they faced the deterioration of the political conditions in central Europe. In the past two decades, their politics and texts have preserved Havel’s moral high ground, but gradually lost their influence over real politics in their societies. Today, their voice is present but marginal, and thus riddled with frustration, defeatism while still feeling self-righteousness.

Viktor Orbán: A rake’s progress

Unfortunately, there exists an extreme alternative to Havel’s involvement in politics, one where the intellectual decides to reject any moral standard and enters the gutter in pursuit of sheer power. This has been the case with Viktor Orbán, who by any standards was an intellectual before and for a few years after 1989. To many, the choice of Orbán as an intellectual might seem odd today. He is now a shrewd politician and an autocrat. Yet he was one of the founders of Fidesz, established in 1988 by young Hungarian intellectuals and dissidents.

Orbán deliberately decided to shed his intellectual stance. He realised that, as the head of a liberal intellectual party, he could attract only a small percentage of the electorate. He craved power and popularity and was willing to do anything to achieve it. Being an intellectual, he could figure out, from the history of political theory, a whole arsenal of strategies to attain and retain power. First, he paralyzed the independent media and used extreme nationalist rhetoric to outdo the neo-fascist Jobbik party. Then he changed the constitution in order to protect his position while still allowing for democratic elections. When, in 2014, he cynically described his policies as ‘illiberal democracy’, he was right. It reflects the way the term was first defined and described in 1997 by Fareed Zakaria. For Zakaria, illiberal democracy allows elections but fully undermines the rule of law and freedom of the press, and corrupts democratic institutions. It is a blueprint for and image of contemporary Hungary.

The story of Viktor Orbán is fascinating and scary at the same time. It was in Vienna, where that English editor mused recently about the role of intellectuals in central Europe, that Hungarian intellectual and writer György Dalos, speaking a decade earlier, told me a story about his former friend Viktor Orbán and his political and intellectual volte face. Sometime in the early 1990s, Orbán met him and told him that his Fidesz party could not, through liberal democratic discourse, exceed five or six percent of the vote – and so he had decided to turn to nationalism to propel his political ambitions. Orbán insisted on telling his friend this, aware that it would most likely finish their friendship. The pangs of a failed intellectual, perhaps.

They parted, Orbán to become prime minister – indeed, he now seems to be prime minister for life – while his former friend, Dalos, continues to live in ‘exile’ in Berlin, the place where many central European intellectuals and artists have found refuge for the past three decades.

Walter and Tamás

So what option is open to central European intellectuals today? How can they maintain their independent stance and moral principles, yet find a position where they can support democracy in their countries? This is a particularly pressing question today, when central Europe is again traversing a rocky road paved with nationalism and populism. The answer is neither simple nor easy. An intellectual must decide for himself or herself, and must have the option of exit – withdrawal to privacy – as a legitimate choice when facing a ruthless political regime. However, to be a voice in the public space today, and not to fall into the Havel or Orbán trap, it is not enough to be critical of the political status quo. Individual action towards another person or a cause defines one’s intellectual outlook. I will demonstrate this with a story.

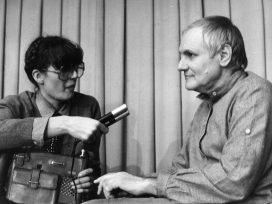

Walter Famler, an Austrian intellectual, publisher and activist, has for decades exercised his ‘voice’ by criticizing the politics of his native country, calling it – somewhat overdramatically – a fascist state. We, his friends, often regard these alarms as Walter’s exaggerations, as melodrama accompanied by a nod and a wink. He talks in hyperbole and admires a wide range of prominent figures and radical movements. In the past it was Lenin, Castro, Tito’s Yugoslavia, Malcolm X, Muhammed Ali and Yuri Gagarin. More recently he has identified Herbert Marcuse and iconic Dialectics of Liberation as yet another opportunity to confront, and even overthrow, the capitalist order. So far, one might say, a middle-aged, middle-class leftist intellectual.

Yet it is his reaction to concrete suffering that stands up, and that defines and separates him from the chattering class of intellectuals. A few years ago, a Hungarian living in Vienna told him that her homeless brother had been shot on a street in Budapest and was in hospital. At the time, supporters of the neo-fascist Jobbik party boasted of shooting homeless people in Budapest. (Missrathene Volker have no right to existence, they would say if they read Nietzsche at his worst.) She also told Walter that her brother, a painter, was mentally unstable. She brought him some of his sketches. He perused those pictures of a tarnished human being and an artist, reflected on his fate and prospects, and was moved to act.

For the past three years, Walter has helped Tamás Bakos in various ways: encouraged him to paint, let him stay in his house, organized an exhibition of his works, helped his family, and had a modest house built for him in his native village in eastern Hungary. Bakos now paints and has regained his dignity and composure. He has, thanks to Walter, been reborn. It is this human response to the suffering of a fellow human being, and not just his words, that distinguishes Walter as the intellectual at his best. It is the act of human compassion that offers intellectuals in central Europe an escape from the lures of the Havels and Orbáns of this world. The former is the temptation of vain moralizing; the latter is the embrace of the lowest human instincts of avarice, vainglory and a thirst for power.

The first president of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, who was a philosopher and intellectual, stressed his whole life the importance of ‘small work’ (drobní práce) as the most important goal in one’s endeavour regardless of his or her status; a realistic goal one is able to achieve and that has an evident benefit for an individual or a cause. In this respect, ‘exile, voice or loyalty’ for central European intellectuals has to have a concrete aim that does not blab in universal terms or global ventures that always fail, but one that focuses on achievable efforts that make life meaningful and beneficial for oneself and society. Be it helping a homeless person, a Roma, or immigrant, pursuing to deal with small injustices, is what counts. That is superior to continuously lamenting about the crisis of liberal democracy, admonishing the majority for electing a populist, or giving up on any action and declaring that the world is hopeless.

Mind you, Masaryk’s credo of small work did not stop him, in his 70s, from leaving his country. In 1918 he became the president/liberator of a new country – Czechoslovakia. Yet an independent Czechoslovakia was never in his plans before 1914 when it was utterly unrealistic. It was a small opportunity that circumstances of the Great War offered and he latched onto it. Thus, a choice exists today for central European intellectuals whether it is in the breadth of Havel, Orbán or Walter.

See the works of Tamás Bakos at www.bakos-t.org

Walter Famler is member of the Eurozine Advisory Board, as is the author, Samuel Abrahám.